Of all the unexpected systems that the pandemic has laid bare, the crisis has shown childcare to be uniquely scattered and broken. By closing down the backbone of childcare for most people — the public school systems — families were left scrambling to make do. The news report euphemism was “balancing” childcare responsibilities. From inside, it felt more like “plummeting towards spikes and alligators.”

What was uncovered is an amazing thing about childcare in this country. Unless people had a uniquely good or bad experience, we don’t talk about it. It’s regarded as a very personal decision for each family unless it extracts from the workforce. Once an economist is involved, we pay attention as childcare is a drag on the economy or lack of childcare is a remover of employees. The pandemic is showing exactly that, with millions of mostly women remaining out of the workforce until childcare options stabilize.

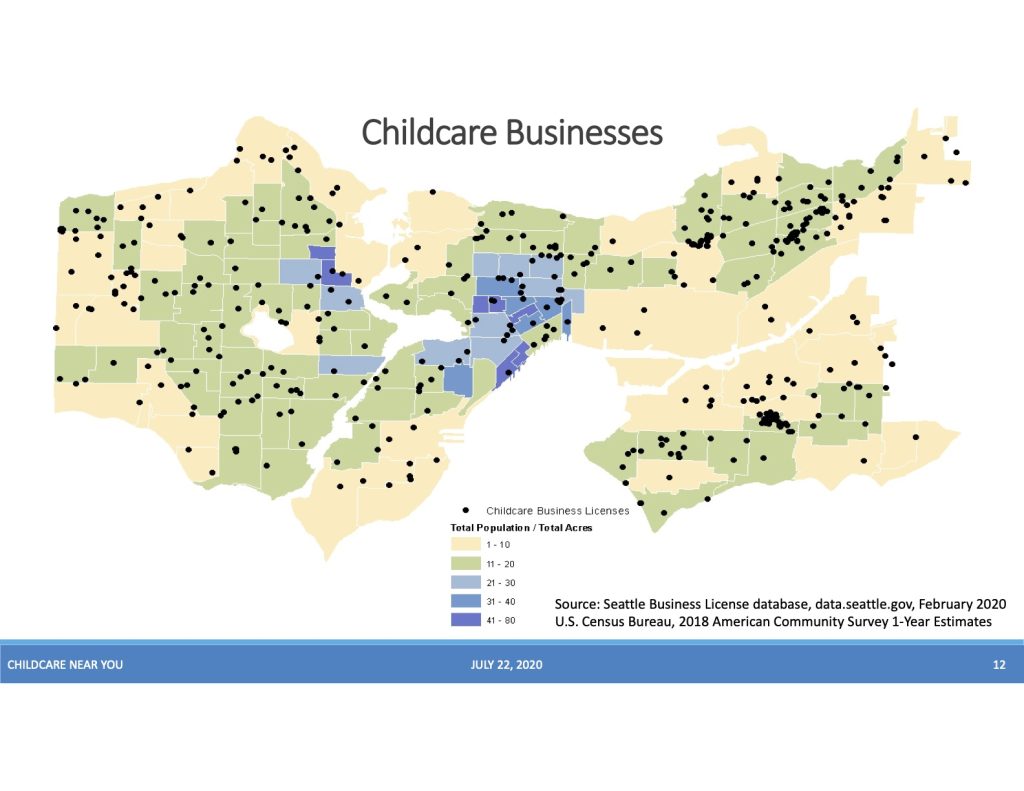

This shared difficult experience is prompting folks to talk about how and where our children are cared for. What people have found in finally comparing notes about childcare is not so much a monolithic industry, but fragmented array varied by price, location, and service. Care facilities are defined less by where they are, but by where they are not.

As leaders start to ask “why?”, we are seeing something that’s missed by looking at childcare through an employment lens. We’re seeing how neighborhoods are missing a vital component to making them complete places.

Undervalued

One of the leaders trying to get a handle on the issues around childcare is Seattle City Council President M. Lorena González, who is running for Mayor and was The Urbanist’s June meetup guest. She puts access to care in terms of building a hospitable city. “Childcare is key if we’re serious about creating complete and livable neighborhoods that people can feel like they can step out the door and the neighborhood right for their families.”

The Governance and Education Committee which González chairs heard testimony from childcare providers outlining issues opening and maintaining childcare facilities. “We heard how we could make a difference in that space. Make sure they’re prioritized in processes just like affordable housing. Giving these small business owners assistance they need navigating the bureaucracy.”

This is a second, broader push to increase Seattle’s childcare in less than a year. Last summer, the council passed Councilmember Dan Strauss’ “Childcare for All” legislation that reduced the regulations on home-based childcare and childcare centers in residential zones. Testimony in that earlier legislation revealed several stark pieces of data. Seattle has approximately 33,000 children under age six whose parents work outside of the home. There are 16,400 childcare spaces in the city. Half the city’s census tracts are “childcare deserts.” This demand has pushed the cost of childcare into the in-state university range.

That demand doesn’t translate to staff wages. Across the three county metropolitan region (King, Pierce, Snohomish) the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) counted 2,660 childcare workers making an average of $35,120 per year. That is half the number of exercise trainers for the same area, who make on average $24,000 more per year. Childcare tends to be one of the lowest paying personal care and service occupations tracked by BLS, making 80% the average annual wage in the category.

Teachers are a separate category. As a group, all teaching jobs pay double childcare work. But it breaks down in the smaller categories. The region hosts three times the number of pre-K teachers as childcare workers — 6,850 — who make just about the same wage of $37,050. This would be approximately $18 per hour. We undervalue childcare across the board.

Thinnest Margins

Katharine Green is intimately acquainted with these figures. After 25 years working in childcare, she has experience in centers and programs for all age groups. Since 2005, she has run a family home childcare program for infants to school age children. Via email, her advice for starting a childcare business: “Do the research for childcares in their area and have a plan of how you will exit at age of retirement.”

Getting to that retirement can be very tight and hit a snag in many different ways. Green added an extra bathroom to the childcare space in her home. Otherwise, everyone had to go up stairs “to maintain ratio” or keep the correct number of children to a supervising adult. The addition was expensive. “A lot of the things I was able to do was because my children are grown and I don’t have a whole bunch of extra costs. I’m not raising my own children any more.”

For other providers, such an expense can end their operations. According to Nicole Traore Early Head Start Lead for Child Care Resources who also testified at the Governance and Education Committee, “childcare is not a big for-profit business. Many just have enough to make it from month to month. If they’re hit with a modification, they often have to close because they don’t have the means to pay.”

“Sites are literally $5,000 to $10,000 from opening,” Traore says. “One-time support would make a huge difference.”

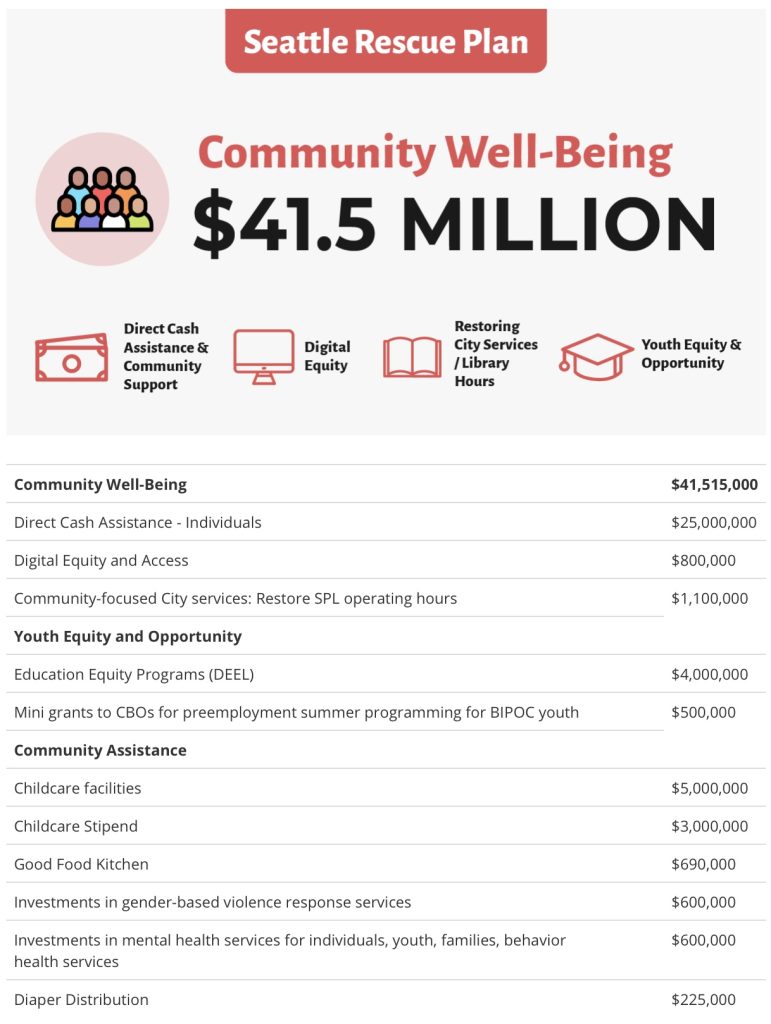

To help with that issue, the newly unveiled Seattle Rescue Plan includes several lines of funding for childcare. From the expected $128 million in American Rescue Plan money, the announced proposals include $3 million for a childcare stipend, $5 million for childcare facilities, and several million more in supports for small businesses and scholarships for childcare services.

Increasing capacity

A more regulatory issue also arises in setting up new childcare facilities. Haggard Childcare Resources operates eight Montessori schools in the city, serving 600 families. Casey Thoreen is managing the work to open a new facility to replace their Seattle Children’s Hospital location. The hospital had to make some hard decisions with its limited space and the childcare facility came up short. Thoreen empathizes with the hospital, “What a terrible decision that had to make. ‘We’re going to take childcare away from you.’ You’re our nurses and providers and it was a contentious time between the hospital and their families.”

The school’s new location will be a ten-minute drive north of the hospital. When it opens. Which is in a state of flux.

The initial issues were ones of timing. It took months for the school to get into the door for initial conversations with the overwhelmed Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI). A feasibility meeting took two months. An initial plan meeting was set 126 days out. And there were 16 weeks of delays for the plans to be returned. In total, the school paid for 295 days of rent before work was approved.

The building code has also been a nightmare. A designation by SDCI that the renovation will be a “substantial alteration” to the existing building compelled a full design review and build out of the new space. This red tape added months to the schedule and boosted the budget from an $800,000 renovation has turned into a $2 million project. Thoreen points out that given the 104 licensed childcare spaces that will be created in this space over the 15 years of our lease, the school will never recoup this investment. Fortunately for the families that depend on Haggard for care, Thoreen says, “We are educators first and business folks second.”

To González, the Haggard story highlights the importance of technical assistance for childcare providers. To expand childcare in the city, these providers need help to navigate the bureaucracy. Similar to the city expediting permits for affordable housing, SDCI can. González said, “So we’re hearing providers tell us: ‘Look we’re not business people. We’re in the business of taking care of children. Help us if you’re serious in addressing the issue in our city. We need your help to be set up for success.’”

Rebuilding (or really building for the first time) childcare

This article is a little over a week late. (Editor’s Note: two weeks.) Childcare in these last days of a weird year has been withering. Shuttling kids to irregularly scheduled school, on-and-off remote work, the countdown to some kids getting vaccinated, all atop the pandemic. The ten-year-old took an afternoon nap today. She’s exhausted. I’m exhausted. And we’re not alone.

Giant societal issues are much easier to fix if we just relabel them individual moral failings and shame people into feeling bad they’re doing something wrong. Your are not taking care of your kids the right way. But when we take a moment to compare notes, we see no one is making individually wrong decisions about childcare. We’re all doing the best we can. There’s just some really ridiculous bigger stuff going on. Bigger things like antiquated code enforcement and undervaluing childcare workers. Things that we don’t get to glimpse if we’re not talking.

And that goes to the larger question of what childcare look like in a just city. Council President González has no qualms about calling it infrastructure.

“Childcare that’s diverse and accessible for your family regardless of the care you’re looking for. That’s the vision. That’s the goal of addressing childcare in our city,” González said. “Like transit, childcare is multimodal. Which adventure at which time of the day. Childcare should not be an exception.”

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.