Recently on a cool May afternoon, a group of protestors gathered in Victor Steinbrueck Park brandishing signs that read “Sweeps Bring No Compassion” and “We Need RV Safe Spaces.” These protesters came together to announce the arrival of a new coalition called House Our Neighbors!. The coalition, which includes a number of people who are currently or formerly unhoused, was created to oppose Compassion Seattle, a proposed city charter amendment that could make its way to this November’s ballot.

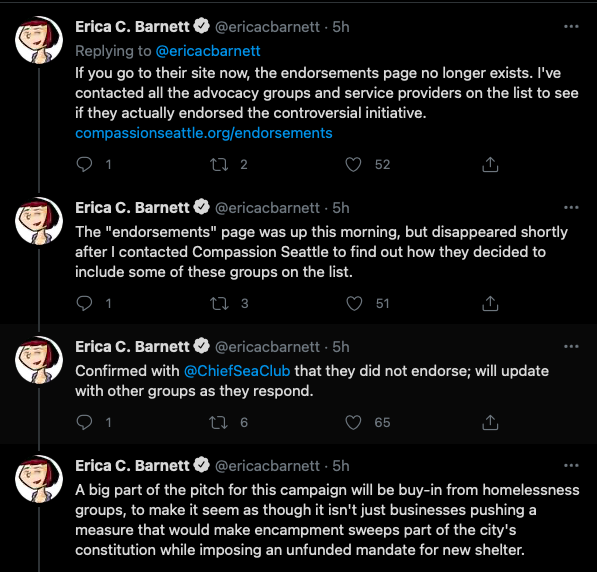

Led by former city councilmember Tim Burgess, the Compassion Seattle initiative has strived to highlight its consensus-driven approach to addressing the city’s homelessness crisis, often highlighting endorsements from prominent players in both the pro-business and nonprofit communities. However, the level of support from homeless advocates has been called into question by both overt adversaries, like House Our Neighbors!, and at least one former purported endorser, Chief Seattle Club.

As reported by The Stranger, Colleen Echohawk, mayoral candidate and former Executive Director of the Chief Seattle Club, criticized the charter amendment during a recent forum on homelessness. This led to sleuthing by Erica C. Barnett of Publicola that called into question whether the amendment had actually received the endorsements from community organizations it claimed to have. As of May 27th, the endorsement page has disappeared from Compassion Seattle’s website.

This falls in line with the criticism from the organization that comprise House Our Neighbors! which argues that the charter amendment is unrealistic and anything but compassionate.

“How Compassion Seattle is rolling out is: This is the Holy Grail that’s going to solve homelessness and visible poverty,” said Tiffani McCoy, advocacy director at the street newspaper Real Change, in an interview with the Seattle Times. “And I want voters to know this is not going to solve all of the issues.”

Earlier in May, Real Change, along with organizations the Transit Riders Union, Nickelsville, and Be:Seattle, filed a legal challenge against the proposed amendment arguing it contains misleading or inaccurate language. As a result, signature gathering for Compassion Seattle was placed on hold until May 27th. However, in lockstep with the debt of signature gathering, House Our Neighbors! continues to escalate their opposition, notably by gaining apparently genuine endorsements from community organizations and candidates in Seattle’s upcoming mayoral and city council elections such as Andrew Grant Houston (Mayor) and Nikkita Olivier (City Council Position 9). The coalition is also seeking to amplify its voice through tabling by volunteers at locations across Seattle.

House Our Neighbors’ Case Against Compassion Seattle

House Our Neighbors’ opposition to Compassion Seattle is centered on the premise that the proposed charter amendment presents false narratives about both the reality of homelessness in Seattle and what measures are necessary to put an end to the crisis. Their argument against Compassion Seattle can be broken down into four main parts:

- 1. An unfunded mandate

- 2. Insufficient new housing targets

- 3. More encampment sweeps

- 4. Ignores people living vehicles

Part 1: An Unfunded Mandate

The first major point of opposition from House Our Neighbors! focuses on funding. According to Compassion Seattle’s promoters, it is unnecessary for the amendment to require new revenue to fund the affordable housing and wrap around services it mandates because the amendment will require the City to allocate a portion of the City’s general fund (approximately 12%) to human services. Its cost fact sheet, published by SCC Insight, estimates that if the requirement were in effect this year, about $18 million in addition funding would be directed into the human services fund, bringing the total up to nearly $193 million. In the words of the campaign, the true issue is not a lack of funding, but an absence of “prioritization” of funding, which Compassion Seattle claims a city charter amendment would ensure.

But when inspected more closely, the 12% general fund allocation for human services barely rises above the City’s 2021 spending in which 11% of its funding, or $175 million, was spent on human services. Granted that funding was not mandated, and thus could be subject to change in future years.

Speakers at the rally for House Our Neighbors! decried the no new revenue approach, claiming that spending only $18 million more to end homelessness would in fact “barely make a dent in this humanitarian crisis.”

Research exists to backup this viewpoint. In 2020, consulting firm McKinsey published a report including costs estimates for what level of financial investment would be necessary to end homelessness in King County.

Using a conservative set of assumptions, ending the homelessness crisis in King County would therefore cost between $4.5 billion and $11 billion over ten years, or between $450 million and $1.1 billion each year for the next ten years. To put it another way, ending homelessness in King County would require spending three to five times the approximately $260 million currently spent locally on homelessness and [extremely low income] housing in the region.

Credit: Why Does Prosperous King County Have a Homelessness Crisis? McKinsey & Company, 2020

While McKinsey’s financial projections cover King County as a whole, Seattle’s price tag alone would still easily run into the billions of dollars range since using data from the 2020 Point in Time Count, roughly 70%, or 8,166 out of 11,751 people counted as unhoused were living in Seattle.

As a response to the unfunded mandate argument, supporters point to additional funding that could come from the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021. They say Seattle is poised to receive $800 million in funding from the bill, and proponents of Compassion Seattle argue that some of that funding, along with donations from private entities, would be sufficient to handle the crisis. Mayoral candidate Bruce Harrell, who has backed Compassion Seattle, argued an additional $20 million to $30 million should go to homelessness in the City’s recently announced disbursement of $128 million in ARPA funds, which invested $49 million in housing and homelessness. Harrell hasn’t said what should get cut from the plan to find the extra money, except for a $7 million IT investment he criticized.

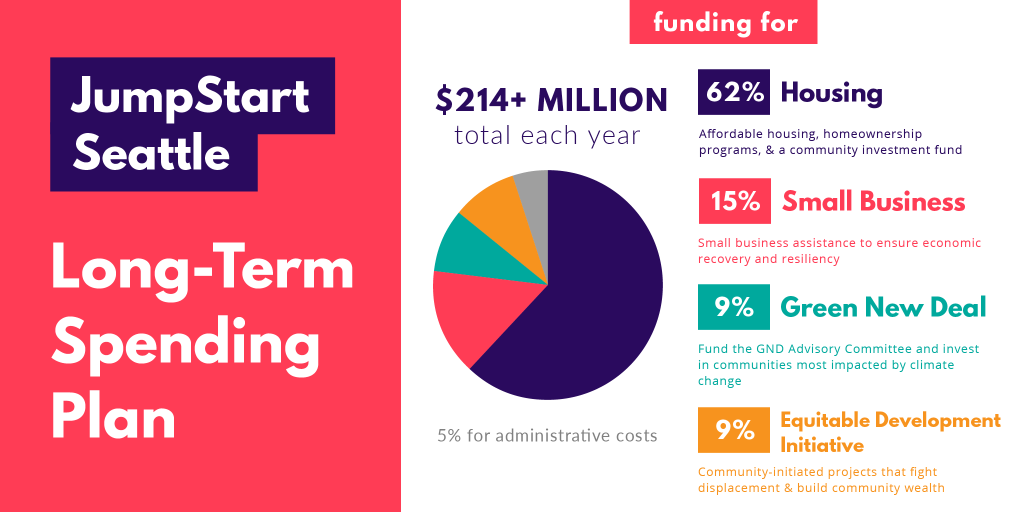

The City’s recently passed JumpStart Seattle has also been pinpointed as a future source of funding. However, as Doug Trumm reported for The Urbanist in April, former Councilmember Burgess, who has specifically named JumpStart Seattle as a potential source of revenue, has a history of opposing business taxes in Seattle, including the head tax which preceded JumpStart Seattle. Additionally, Rachel Smith, President and CEO of Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, has formally endorsed Compassion Seattle, while her organization has taken the City of Seattle to court in an effort to declare the JumpStart Seattle tax as illegal.

Identifying the JumpStart Seattle tax as possible form of revenue to support the mandate has also been viewed as problematic by housing advocates who have pointed out that the funding raised by the tax was intended to pay for the construction of affordable housing developments, not to fund emergency housing like tiny house villages and enhanced shelters.

Perceived failure to make progress could be one reason why voters may be reluctant to pour more money into ending the homelessness crisis. According to polling from Compassion Seattle, while 57% of respondents said that homelessness was the issue they were most concerned about, 73% of respondents supported the Compassion Seattle plan to reallocate funding rather than raise new revenue. Katie Wilson of Crosscut said this is akin to asking children if they want a pony. 73% of the children might say yes, but that doesn’t mean their parents have the money to buy them one.

Part 2: Insufficient New Housing Targets

If the Compassion Seattle city charter amendment is approved by voters, the City will be required to create 1,000 new units of affordable or emergency housing within one year of its passage, and an additional 1,000 units the year after that. House Our Neighbors! argues that the target is far too low to meet demand.

Because of the high cost of creation affordable housing, it is likely the vast majority of new housing created as a result of the mandate will be emergency housing. This will continue a trend of increased investment in emergency housing by the City that goes back to 2017. According to data provided by the City, the amount of spaces available in enhanced shelters and tiny house villages doubled from 1,004 in 2017 to 2,100 in 2021. To put that number in further context, additional data from the City reveals that since 2017 over 6,200 affordable homes have been created or preserved in Seattle. The cost of these affordable homes amounted to $1.7 billion, including $400 million of City funds.

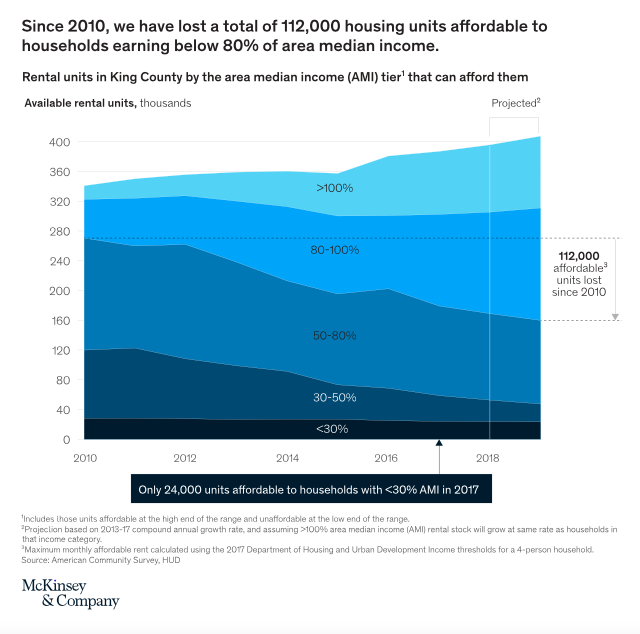

However, even with the creation of approximately new 7,300 affordable or emergency homes, the number of people living unhoused in Seattle remained roughly the same from 2017 to 2021. That is likely because dwindling housing supply and surging prices have resulted in a striking loss of affordable housing regionally. According to the McKinsey report, about 112,000 housing units affordable to households earning up to 80% of area median income in King County were lost between 2010 and 2018. These figures give heft to opponents’ argument that the 2,000 units of affordable and emergency housing mandated by Compassion Seattle would represent a drop in the bucket.

Part 3: More Encampment Sweeps

The topic of encampment sweeps has emerged as a flashpoint of opposition against Compassion Seattle, and it was omnipresent at the House Our Neighbors! coalition launch event where Paige Owens, a former Real Change vendor and current advocacy intern, related her experience of watching sweepers pile the tent in which she lived and her personal belongings in a truck. After returning Owens her backpack, the workers conducting the sweep refused to return her tent. “I was devastated. I had to either to stay with someone else in their tent, go beg for another one, or steal one,” said Owens in a statement that was rebroadcast on Twitter. “I don’t know if you have ever had to ask someone for a favor but it can be really degrading to walk by without a glance or even a thought as to what you might be going through.”

Criticism over the provision to authorize sweeps once Seattle reaches the affordable and emergency housing targets mandated by the amendment has led to a revision in the language used to describes the City’s power in this area. Previously the amendment stated that encampments could be removed even if the City was unable to place individuals impacted by the sweep into safe and secure housing; however, the revised language now asserts that the City’s policy would to avoid encampment removal unless the encampment “poses particular problems related to public health or safety or interferes with the use of the public spaces by others.”

Councilmember Kshama Sawant (D-3) decried the amendment’s language surrounding sweeps in a recent op-ed for The Stranger in which she wrote, “For the first time ever, if this charter amendment passes, the sweeps of homeless encampments would be enshrined into the city’s most foundational legal document with the explicit declaration that there is ‘no right to camp in any particular public space.'”

In a guest contributor post for The Urbanist, Ron Davis also tackled the thorny topic of sweeps but landed at a different conclusion than Sawant.

From a pure statutory standpoint, the amendment narrows the scope for removals in two ways: It puts refreshing limits on how people are removed, by requiring individualized interventions, which pay attention to culture, family structure, and disability. It also acknowledges the possibility of harm from encampment closures. These will guide the city to more appropriate action and give the aggrieved grounds to challenge the manner in which removals take place.

Ron Davis, How to Improve Compassion Seattle’s Charter Amendment, The Urbanist, 2021

Davis recommends making the language around encampments sweeps “clearer and more prescriptive.” To that end, he suggests making the requirement for housing availability prior to encampment removal more explicit, providing specific examples of public spaces, and clearly defining what constitutes as interference. [Davis did not support the proposed charter amendment.]

Part 4: Ignores Vehicle Residents

According to the City of Seattle, nearly half of city’s unhoused residents live in vehicles. However, the Compassion Seattle charter amendment makes no reference to people living in vehicles, nor does it make any provision for addressing this population’s specific needs.

Vehicle resident and member of the House Our Neighbors! coalition, Dee Powers believes this a critical oversight. “I’m not service resistant, I simply haven’t been offered something that fits my needs,” said Powers in a statement read at the event. “Compassion Seattle is now doing the same.”

Powers, along with other homeless advocates, called for the City to establish safe parking zones. However, while safe parking zones may seem like an easy solution, Seattle has struggled to get neighborhoods to accept them. Furthermore, the cost of safe parking zone pilots run in the U District and Ballard exceeded expectations, leading the City to lean more heavily into other emergency shelter options like enhanced shelters and tiny house villages.

Still homeless advocates have expressed worries that by focusing solely on people living unsheltered or in tents, Compassion Seattle further distorts the reality of homelessness in the city.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.