King County Executive Dow Constantine is seeking a fourth term. His campaign war chest is vast and slate of endorsements is impressive, but for the first time he faces a credible progressive challenger in State Senator Joe Nguyen (D-White Center). Constantine is touting his record and pointing to his leadership on crafting Sound Transit 3, establishing the County’s Regional Homelessness Authority, and responding to the Covid pandemic.

“Honestly, I think the response to a global pandemic has really shown what it means to have good leadership, not just at the County but in a lot of our governments,” Constantine said. “We were the first place to experience a genuine outbreak of the novel coronavirus. We had no roadmap. We had precious little help from the [Trump] administration. But we led with science.”

“Ultimately we achieved the best results of any of the largest three dozen metropolitan counties in the country in terms of the lowest rates of death and infection,” Constantine added. “And that stands us in a stronger position for the recovery to come. That really is a proud achievement, and it’s no exaggeration to say we saved many, many lives.”

Constantine reiterated many of the same points in his State of the County speech earlier this month. Unlike Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan, whose six-minute State of the City speech focused almost exclusively on the pandemic, Constantine also highlighted a number of other achievements and goals in his annual speech. Our interview covering his reelection platform tackles it more thoroughly.

ST3: “This was a personal mission”

Looking back to his previous term, Constantine said passing the Sound Transit 3 (ST3) package was perhaps his proudest achievement of all, and getting it done on schedule will be a major focus for him. He stressed that Sound Transit should be focused on what it takes to build the package on time rather than dwelling on cuts and delays.

For the last year, the agency has engaged in a realignment process, fretting as a budget shortfall or “affordability gap” was projected at $12 billion due to escalations in project cost estimates and dips in revenue projections due to Covid. The affordability gap has since been revised down to $8 billion as revenue projections have rebounded.

Constantine chaired the Sound Transit Board of Directors during the pivotal time period when the agency put together the ballot measure and oversaw the campaign that successfully passed ST3 in 2016. As County Executive, he’s still on the board, but the chair position has rotated to University Place Mayor Kent Keel. Chair or not, Constantine still is heavily involved and treats ST3 as his baby.

“We created a vision, and went to the Legislature and lobbied for a long time for authority. We got some clumsy but workable tools from the Legislature. We created a plan. We created a campaign; we got it passed,” Constantine told me. “And now we are going to build it.”

“This was a personal mission that I went on when I got on the Sound Transit Board,” Constantine added. “I knew this was something that needed to happen for the growth of our region and for the environment, and I went out and made it happen, and we rallied the community and really all sectors to the cause.”

Adjustments needed to keep ST3 on track

While proud of Sound Transit’s work, Constantine wasn’t shy about criticizing the agency about alignment decisions that have added costs in a rather clumsy fashion. In our reporting, The Urbanist highlighted the most egregious example when the agency claimed it’d need to tear down 306 apartments at a cost of about $250 million to site West Seattle Link — despite a perfectly adequate Fauntleroy Way right-of-way sitting right next to these brand new buildings.

“It’s just stupid,” Constantine said. “They pick a route; five years later someone has built an expensive building in the way. The response is well that building is worth X million dollars; that’s going to be added to the cost. No, it’s not! You’re going to go around the building. You’re going to pick a different way. And that’s the thing I’m talking about here. It’s like, are we incapable of adjusting as we go? Are we incapable of iterating? Are we incapable of dealing with the circumstances as they come? No, I don’t think we are. A lot of these cost overruns are based on stubbornly pressing ahead when the landscape has changed and we need to figure out a different way to get to the same result, and that’s what I’ve been pressing us to do, and a number of boardmembers agree with me.”

One route that Constantine still wants to pursue is tunneling West Seattle Link and Ballard Link at Salmon Bay. He argued further study may reveal that tunnel routes are similar in cost to elevated routes, suggesting the estimates are already converging. Early estimates put the cheapest West Seattle Link tunnel option at $700 million more than the baseline elevated option. The January cost updates brought the two closer together, but part of the narrowing was the aforementioned unreasonable property acquisitions added to the elevated option.

“It is just a question of the balance between the utility and the cost. I do think there’s something to be said for really pushing on places if you can figure out how to close the cost gap because you avoid a whole bunch of other challenges, including right-of-way acquisition and conflicts with other uses,” Constantine said. “More design and more intensive like sharper pencils on this will lead you to the right solution.”

“At some point you either figure out there’s not that much difference in cost between tunneling and elevated when you consider costs broadly, or you figure out that there’s just no way to make tunneling work and here’s the best place to go elevated,” he added. “But we’re at such an early stage still of design and engineering that we just don’t have information to come to those conclusions.”

While Constantine isn’t ready to give up on the West Seattle light rail tunnel yet, he is certain that the station needs to be pointed south toward expansion, as Seattle Subway has urged.

“I’m the first person to call BS on them trying to have the station end up in an east-west orientation in West Seattle,” Constantine said. “We’re going south. We’re going to White Center. We’re going to Burien. You can’t have the tunnel land as though the next stop is Vashon Island.”

Nguyen’s transit critiques

Nguyen has sought to take that transit issue away from Constantine somewhat, arguing he’d be the more effective negotiator to keep ST3 humming along and a further “ST4” expansion behind it. And since the strongest case for the West Seattle tunnel will likely be predicated on the elevated option having major cost overruns (some very avoidable), he may have an opportunity there. Nguyen also has insinuated that Sound Transit CEO Peter Rogoff should have been removed for his anger management issues and leadership failings, which is another break from Constantine.

Nguyen has focused on eliminating fares through his ‘transit for all’ plank, backed by Transit Riders Union’s ORCA for All campaign. Meanwhile Constantine has supported the more incremental step of offering a free fare program for low-income riders. The King County Council passed the program in February 2020, but the pandemic disrupted rollout with Metro suspending fares for all riders in March in response to the pandemic. Metro reinstated fares in October. Both have stressed boosting transit service to further a strong recovery from the pandemic and reduce climate emissions.

Countywide bus ballot measure

Executive Constantine pledged to put a countywide measure on the ballot to fund RapidRide expansion (as laid out in the Metro Connects plan) and bus electrification. “It has to happen,” he said, adding they could tackle both Metro Connects and electrification. The County Council had been gearing up to put a measure on the ballot in early 2020 before getting second thoughts when the pandemic hit and abandoning the plan. Seattle proceeded to go it alone and passed its bus measure with more than 80% of the vote — seemingly enough to carry the whole county had it been countywide.

At the same time, Constantine stressed the need for the state to pass progressive revenue options if not full-scale progressive tax reform in order to untie the County’s hands on raising new revenue. The sales tax and property tax options they’ve been given are regressive and becoming untenable to keep expanding over and over again, he argued.

“We need them to focus on dialing back the regressive sales tax,” Constantine said. “And focus on taxes that ask you to pay based on how much you make and how much you have, and if we had a state tax system that did in this economy, we’d be able to accomplish everything we need to accomplish without breaking a sweat, rich or poor.”

While making the tax code more progressive in incidence sounds good, it is a heavy lift that could delay passage of a countywide bus package if those progressive revenue options don’t solidify soon.

For now, Constantine has said his strategy is to lead with more transit service to entice riders back to Metro as we come out of pandemic mode (though Metro is still at about 85% of service levels pre-pandemic). “I believe we need to be there with the service when people are ready to travel again so we can not have people get into the habit of taking their single-occupancy vehicles, so that we can provide the kind of service that people can choose transit as their primary way of getting around.”

Herding cats regionally to solve homelessness

Homelessness is clearly a huge issue for voters this cycle. Constantine argued he’s made headway with a regionalized response with the Regional Homelessness Authority established in December 2019 and the Health Through Housing Initiative to rapidly add about 2,000 supportive housing units by buying hotels and motels.

The state authorized jurisdictions to enact a 0.1% of state sales tax for the purpose of funding affordable housing. The County projected that was sufficient to raise enough funding to issue $400 million in bonds. However, eight cities ended up opting out of the County plan, as the state law permitted them to, preferring to invest the money separately rather than partnering with Constantine’s plan. That will mean a bit less bonding capacity, but Constantine suggested some of the cities will likely come around and join the County initiative, especially when they realize their small piece of the pot of money isn’t large enough to do much on its own.

In our interview, Nguyen saw Constantine’s failure to get regionwide buy-in as a sign of weak leadership, but Constantine has framed it as a temporary setback inherent in “cat herding” — as in coalition building among indifferent or half-hearted participants. And, to be fair, getting Bellevue, Renton, Issaquah, Maple Valley, North Bend, Covington, Snoqualmie, and Kent — the eight opt-out cities — to buy into the same homelessness solution is no simple task. Both agreed they wanted to see new progressive revenue sources dedicated to housing, which might take help from the state legislature.

“We will continue to lobby in Olympia for the tax reform that will allow capacity to build housing that is need for a growing region,” Constantine said. “This misalignment of people’s means and the housing, the shelter they can afford, is just a problem that absolutely has to be solved.”

King County’s Regional Affordable Housing Task Force has projected the region needs 244,000 new affordable homes by 2040 to prevent tenants from being severely rent burdened and displaced. Asked how he would tackle that challenge, Constantine acknowledged it was daunting but pointed to a mix of public investment, incentives, and affordability requirements.

“244,000 is just a huge number of units, but we have to take it on definitely with straight up government subsidies, but also with a whole bunch of other tools that range from incentives to requirements,” Constantine said. “One thing we know is that there is enough space to build all that housing and particularly around transit centers, where you can really reduce the cost to the individual and to the community by having people live and work close to transportation. That’s just the model we have to pursue.”

Tackling exclusionary zoning

Constantine wants to reduce exclusionary zoning and focusing on transit-oriented development in urban areas across the county.

“My entire argument for Sound Transit 3 was that we have invested in highways and the interstate system and in doing so we laid down the blueprint for the development patterns we would have to live with over the course of decades. And creating a high capacity three-county electric transit system with stations ready to accommodate growth is laying down a different blueprint — a blueprint for a more sustainable land use pattern, a blueprint that allows for more people to have more access to more of the opportunity in the region,” Constantine said. “This is the old urban planner in me coming out, but I just think that people so naturally see transportation as a response to demand, but in fact the infrastructure is the thing creates the demand; it creates the reality that we then have to respond to.”

“By creating a framework for growth that is healthy and sustainable, we can ultimately build our way out of a lot of these challenges including housing affordability,” he added.

Many King County cities also seem to be getting lapped by Tacoma when it comes to reducing apartment bans and promoting missing middle housing, particularly in the single-family zoning that pervade outside of circumscribed growth areas near transit stations. “I think most cities are getting it around transit-oriented development,” Constantine said, pointing to Shoreline’s example and adding he thinks cities will follow suit and supports dense infill development and diversity in housing types and incomes in neighborhoods. “Cities need to zone for and, even more than that, incent and make easier that diverse housing within neighborhoods.”

“People use [neighborhood] character to mean only single-family houses or what have you, but I don’t think that’s a thing,” Constantine said. “I don’t think you need to destroy the fabric of a community in order to create much more housing and much more housing diversity within it. In fact, I think having more people of more incomes enhances a community. It makes it more interesting, it makes it more vital, and it makes it stronger.”

Constantine added the County is doing what it can in unincorporated communities where it has jurisdiction like White Center, highlighting the example of the Greenbridge affordable housing project as a project that carefully won community buy in and met local needs.

Policing reform and racial justice

While Nguyen wants to reinvest money from the County’s criminal legal system to social services, shifting focus from a punitive model to a more holistic human needs model. Constantine’s call isn’t quite as bold or urgent, but he did share some of same language and goals. He pointed to moving $4 million in marijuana funds out of the Sheriff’s office and into community-based solutions and removing marijuana convictions from folks’ records.

“We are now embarked on a really intensive community model, not just for policing, but for community safety — one where I anticipate we will seek to ask police to do less, to not solve every problem, but rather to bring human service and public health resources to bear on unwinding community conflicts and helping those that are in behavioral health crisis,” Constantine said. “A complicating factor for us is that we have the policing of the unincorporated area, which is where we are the local government, and then many cities contract with the County, and each of those cities is its own community with its own expectations.”

Constantine argued working through the more complicated process of bringing the whole county along will pay dividends.

“We have to that conversation not just with our direct constituents but with the cities and the city leaders about what their expectations are,” he added. “My hope is that we can keep that whole group together because I believe that the transformation that we want to create in policing should be beneficial not just to the unincorporated area, but to all of those cities, and to the county as a whole. We want everyone to come along, and this is apropos of my previous conversation about cat herding; it just requires a lot more conversation, a lot more patience, a lot more listening, but ultimately I think the result will be a lot better.”

While Constantine has taken heat (including from Nguyen) for his handling of the new $242 million King County juvenile detention center and his resistance to calls to not build it, he professes to share the same goal of ending youth incarceration and reducing the use of prisons broadly. He has pledged to end youth incarceration by 2025 and reduced the number of beds in the youth jail at the behest of No New Youth Jail advocates.

“Our goal, as it is with detention and other parts of the criminal legal system, is to be able to defund the crime and punishment aspects and fund the prevention and healing aspects, and in doing so to create better outcomes for everyone in the community,” Constantine concluded.

Climate action plan

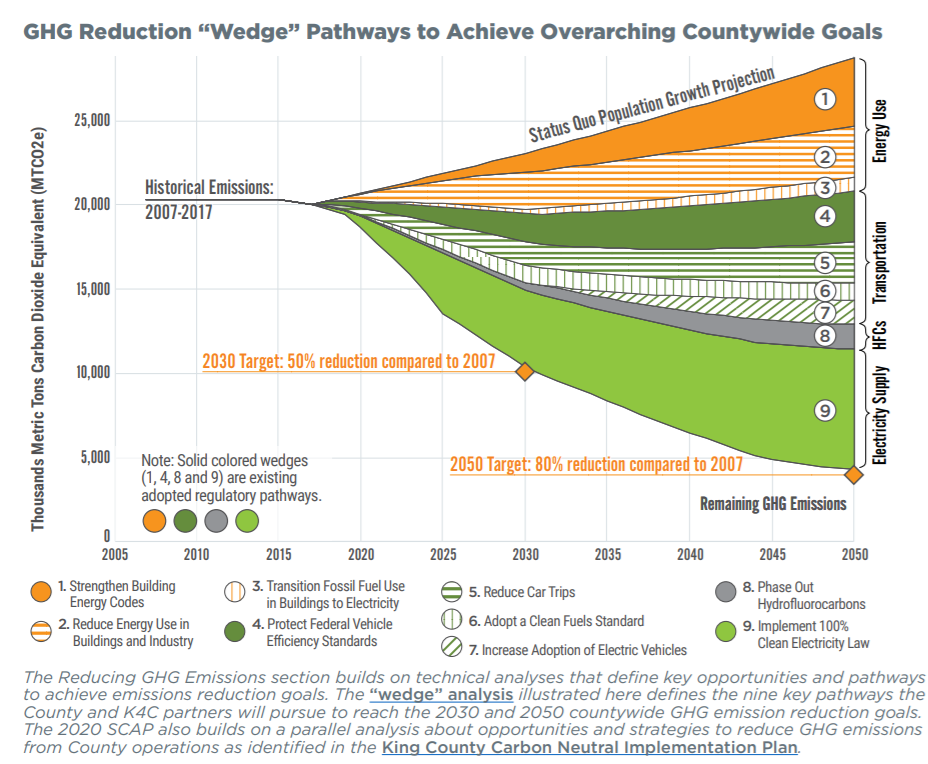

Executive Constantine released a Strategic Climate Action Plan (SCAP) update in May and highlighted it in his State of the County speech. The plan aims to meet the County’s goals to reduce countywide emissions 50% over 2007 levels by 2030 and 80% by 2050. It’s not easy when the County doesn’t control all the levers, he said, but electrifying the transportation system is a key way to get there, as is sustainable deep green building techniques.

In addition to electrification and green building, Constantine said he was optimistic that advances in battery and carbon sequestration technology would provide further avenues for getting to carbon neutral and even reversing the damage from climate change. The County is also using the old-school sequestration technique of planting tons of trees. Constantine celebrated completion of a one million tree planting campaign in April and followed that up by launching a three million tree campaign.

While neither King County, the state, nor the nation has gotten its respective climate emissions on a sharp downward trajectory just yet, Constantine remained bullish that momentum is swinging the other direction and much needed climate action would kick into high gear. From Sound Transit expansions to sustainable housing growth to renewable energy and carbon pricing, the county has reasons to be optimistic. At the same time, we’ve burned through our time to dawdle or drop the ball.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.