The Washington Post covered the national highway system’s maintenance backlog and State Senator Steve Hobbs (D-Lake Stevens) was heavily featured. Despite a record of favoring highway expansions and skimping on maintenance and multimodal investments in walking, rolling, biking, and transit, Hobbs portrayed himself as a maintenance first guy.

Washington State’s highway-widening excesses certainly predate Hobbs, who wasn’t transportation chair in 2015 when the Washington State Legislature passed a $16 billion transportation package heavily focused on highway expansion. However, Hobbs was on the transportation committee and supported that package, and, after becoming chair, has tried three times to pass another package in the same mold.

Some of these issues may not be so obvious if Roger Millar, who is Secretary of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), hadn’t been speaking out against some widening projects and calling for a shift in priorities. Millar has been sounding the alarm about the maintenance backlog and shortfall, including in an interview with The Urbanist, and has also championed high speed rail as a scalable mobility alternative in the I-5 corridor. Despite those efforts, when stacked up against its peers, Washington ranks as one of the worst offenders at expanding rather than maintaining its highways.

“Washington state officials say their experience illustrates the risks of pumping money into expanding roads and skimping on rehabilitation work. The Post’s analysis shows the state the eighth worst in the country for its share of roads in poor condition, at 27 percent. At the same time, more than three-fourths of the state’s spending on roads went toward expansion — fourth highest in the nation,” the Post wrote.

Transportation Chair Hobbs tried to spin his failure to pass a package for the third straight session as a strategic move to allow the state to react to President Biden’s infrastructure plan and “layer on top of it.” Hobbs’s bill made it out of the transportation committee but never made it out of the rules committee and to a floor vote. State Senator Joe Nguyen (D-White Center), who sits on the transportation committee, said he and several progressive colleagues disagreed with the “transactional” highway-centric approach Hobbs has taken as chair, though he did vote to pass the package out of committee. Publicola highlighted the work advocates like the Front and Centered Coalition are doing to raise the issue.

Failing to make it out of the Senate, in turn, meant scant progress on winning over the House to Hobbs’ approach. The House introduced their own transportation package and it was quite a bit different and spent more than twice as much on transit and bike and pedestrian infrastructure. House Transportation Chair Jake Fey (D-Tacoma) spearheaded the bill, and while much of the highway money is still there, the House’s greater commitment to spread more money around to multimodal priorities made it a significant improvement with a greater chance of winning over the progressive legislators it needs to pass.

Meanwhile, Hobbs has shown little proclivity to increase transit, bike, and pedestrian investments. In fact, his proposal tolled buses and taxed urban housing which would actively undermine those causes in order to fund more highway spending. The housing tax was doubly clumsy because it made enemies out of potential allies in the building and development community. Hobbs has also floated levying an added tax on bikes, which would raise very little money, act as a disincentive to biking, and be a middle finger to bike advocacy groups.

Hobbs said his approach would limit spending on “new highways” to 15% in the next package, which was news to us. The only way the math seems to work is by classifying some of the biggest ticket items as solely maintenance rather than expansion even though they add lanes. The “Highway Improvement Program” and “Highway Preservation Program” together consumed $12.27 billion (with both programs including major expansion projects) in a project list released in April.

“Hobbs, the state transportation committee chairman, introduced in this year’s legislative session an $18 billion transportation funding package that included an infusion into road maintenance and preservation while limiting new construction to 15 percent of spending. The passage of that 16-year plan also is key to an ambitious carbon-pricing effort the legislature passed to address climate change by raising billions of dollars while reducing emissions,” the Washington Post wrote.

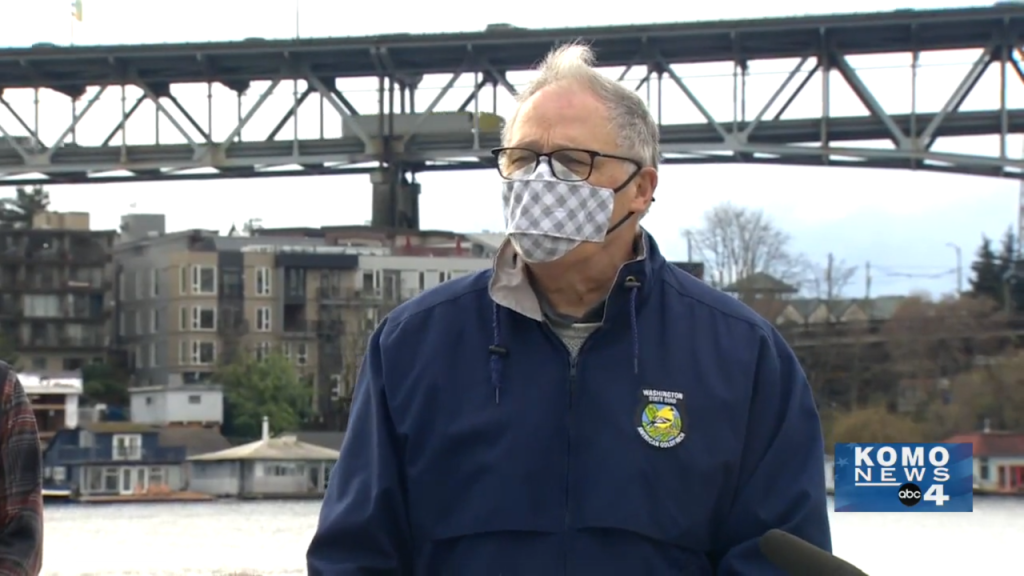

The Washington Post seems to have missed that Governor Jay Inslee vetoed the linkage to the transportation package in the carbon pricing legislation. Future revenue from the Climate Commitment Act (CCA) will fund electrification of the state ferry system and transit, but it’s no longer dependent on the 16-year plan Hobbs had in mind. In fact, it may well be the reverse; Hobbs needs to link his bill to the CCA in order to greenwash the highway investments enough to make them palatable.

Highway spending accounts for a lot more than 15% in his proposed bill, but Hobbs classifies expensive projects like the Columbia River Crossing I-5 project in Clark County — with Washington State on the hook for $1 billion of a project that could cost $5 billion or more — and the $1.8 billion Highway 2 Trestle project in his district as “preservation” projects even though they also widen the roads and beef up interchanges. Rather than getting serious about Washington’s highway expansion addiction, lawmakers are doing linguistic gymnastics to rebrand expansion as “preservation.”

Hobbs’s other highway-widening earmarks include $500 million for SR-18 in Issaquah, $414 million for SR-3 widening in Gorst, $175 million to beef up a SR-520 interchange in Bellevue, $90 million to widen SR-522, and numerous smaller projects. Already we’re passed $4 billion in highway expansion in the big earmarks highlighted, which is more than 22% of the package. The smaller projects appear to add at least a billion more. I’ve reached out to confirm the math with Hobbs’ office and a spokesperson confirmed that they’ve calculated Hobbs’ package as 15% new construction, but are excluding projects in the “preservation” bucket from the new construction tally.

At the end of the day, Hobbs is still willing to make a case for highway expansion; that argument is that Washington is growing too fast not to widen roads. The Evergreen State did grow at about twice the national average over the last decade with 14.6% growth, but traffic and population don’t have a simple 1:1 relationship.

The Ballard Bridge is an illustrative example. Even though Ballard’s population has dramatically jumped over the past thirty years, vehicle volumes on that bridge have stayed essentially flat. State traffic data shows no indication traffic is growing at the same rate as population, and such a policy goal would conflict with other goals anyway, such as those around qualify of life, climate action, and environmental justice.

“Part of the problem you have is just the rapid population increase that’s happened over the last 10, 20 years and the need for infrastructure that matches that,” Hobbs told the Washington Post.

That doesn’t explain how traffic congestion will improve (it won’t) or state climate goals will be met or pollution reduced. It doesn’t explain how putting out more highway bonds so that 44% of gas tax revenue goes to debt service will lessen the maintenance backlog rather than create a bigger crisis for future legislatures. But it does get closer to the heart of the impasse. Senator Hobbs is still a highway man at heart.

And highwayman as he is, Hobbs is the person the Democratic caucus has elevated to guide state transportation policy.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.