It is time for America to get off the highway hamster wheel. Our dull-eyed pursuit of building more highways is a disaster for the climate and the urban environment for little return to even the motorists the highways are supposed to serve best. The empirical data shows that adding or widening highways induce more cars and trips, which means new lanes end up just as congested after a few years time but pumping out more pollution. And yet, America just keeps building more highways and our state is no different.

Despite declaring the Evergreen State a climate leader, the state legislature and governor have failed to change course on transportation. After ladening the last state transportation bill in highway pork, state Democrats seem intent on doing the same with the next one. How can policymakers justify such a move? What benefit are the people of Washington getting to counter the growing costs — in money, in jobs, in emissions, in suffering, in habitat lost, and budgets starved — of adding more highway lanes? Free flowing traffic, swift travel, and dependable trip times? Not when congestion stubbornly persists. So why do the policymakers continue to layer one pork-laden freeway bill on top of another? Why do we let them?

A large clue lies with the first step in any new highway or highway lane’s life: the transportation study. Here, hundreds of pages and dozens of graphs serve to obscure the fact that these studies are more alchemy than science. And this alchemy creates traffic models that predict never-ending traffic growth and then show how new highway miles ease the congestion. When they need to, they even claim less climate emissions by the magic of reduced idling (Myth #1 in our Five Myths of Road Widening). These claims do not hold up to scrutiny, but the absurdity only has to hold up long enough for another turn of the highway hamster wheel. Just long enough for another project to be “too far along to stop now” or “have an environmental impact study completed and ready for federal funding.”

In search of a better traffic model

However, take only a small step back and the pattern of bad decisions following bad models is clear, as a study of California freeway expansions showed a consistent pattern of underestimating how much extra traffic the existence of wider freeways would create and the impact of that additional driving on society. Transportation experts refer to this pattern of congestion persisting or even worsening after widening highways as “induced demand” or the “fundamental law of road congestion”. If our models miss this basic empirical relationship and don’t help traffic engineers, politicians, and the public that employs them to make good decisions, then we desperately need new models. With climate change bearing down and the ongoing human suffering piling up, we are running out of time.

To undo this planet-cooking feedback loop, we don’t just need better numbers, we need a better way to judge transportation spending as a piece of a larger whole. We can no longer ignore that the decisions we make about roads and highways are inseparable from their consequences on where we live, play, and work, and our hopes of avoiding the worst of climate change by building a carbon-free economy for all. It is long past time that these aspects were included in a more dynamic and transparent traffic model that truly reflects the consequences of these decisions and helps our leaders make better ones.

This new model would be a way to better translate the priorities of the people into the transportation system of the future. Instead of talking about climate change and carbon emissions and then building a highway on top of a four-billion-dollar car tunnel or adding lanes while rebuilding a $4.5 billion floating bridge — as Seattle is doing — we could get a sense of the consequences beforehand. Part of the problem with today’s approach is that it has an incredibly narrow goal — free-flowing traffic. Instead we need to broaden that goal and stop presuming the solution (i.e., more cars).

We believe that holistic transportation model must include and provide transparency on (at least) the following five factors:

- Safety;

- Racial justice;

- Land use and Mobility;

- Climate and Environmental Impact; and

- Cost and Jobs.

Predictions will always be hard, particularly those that include human behavior, but the right model — even conceptually — that illuminates the connection between these factors can help the community and their elected leaders make better decisions. Balancing these priorities will take consideration and strong engagement with the community. We are willing to bet that the result will not be a transportation budget that spends 90% on widening highways.

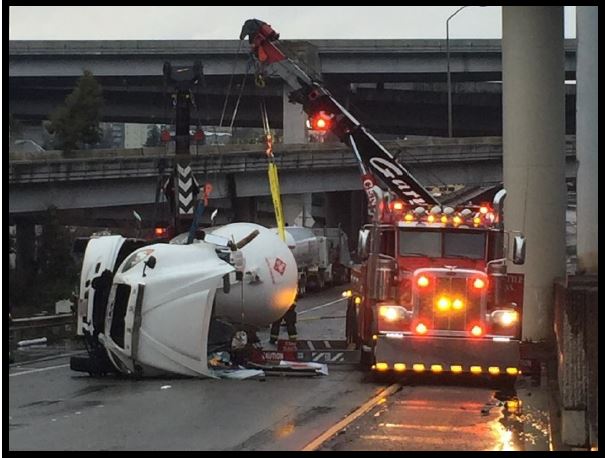

Safety

Highways are not safe. Crashes on state roads are responsible for more than 500 deaths and thousands of major injuries every year in Washington State alone. Nationwide, that annual traffic death figure typically hovers near 40,000. These are unacceptably high numbers of lives cut short and families shattered. Let’s make sure that we design a safer transportation system by explicitly including safety in our models. However, where highway projects are purportedly for safety, they are often a thin veil or easy excuse for highway expansion, as in the added lanes on the SR-520 bridge or the debate over the zombie version of the Columbia River Crossing. By all means, make our bridges safe, but let’s not pretend they have to be wider to do it. A new model would illuminate how the design of our transportation system (speed, roads, and vehicles) inevitably leads to this carnage.

Safety questions a holistic model should answer when considering a transportation investment:

- Does the project get us closer to eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries?

- Does it control motor vehicle speeds and limit conflicts with design interventions in the corridor and nearby streets?

Equity and Justice

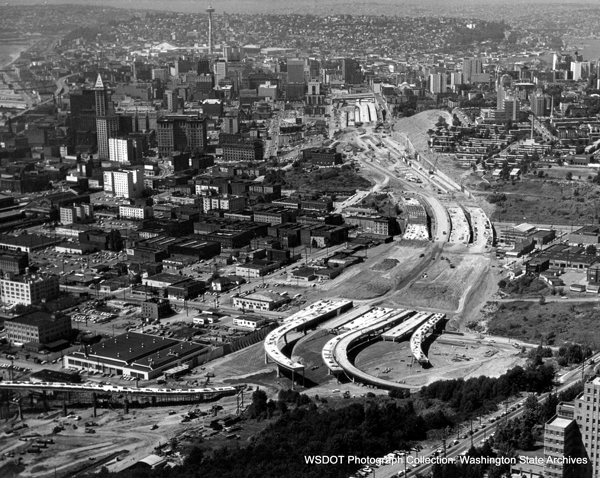

Who are our highways and transportation system for? Many Washingtonians don’t drive and the construction of the highway system displaced whole neighborhoods, and the racism underlying transportation planning meant Black and Brown neighborhoods were frequently targeted. I-5 through Seattle displaced an estimated 30,000 residents. Today those many blocks of land in Cascade, First Hill, the Chinatown-International District, Eastlake, the University District and so forth could have hosted even more residents along with untold destinations.

And beyond land consumed directly, highways cast a long shadow of air and noise pollution that is degrading the area around them and making people sick. Across the country, Black, Latino, and Asian neighborhoods were disportionately targeted for freeway construction, sometimes with “slum clearance” billed as a key benefit of the project. This is one reason why Black and Brown Americans continue to suffer higher rates of asthma and respiratory illness to this day. It’s also why Black and Latino households did not accumulate generational wealth at rates approaching anything close to White Americans living in leafy suburbs those federally-subsidized highways fed.

Racial justice questions a holistic model should answer when considering a transportation investment:

- Is our transportation system accessible to all people?

- Is our transportation — and the people who enforce its rules — safe and welcoming to all people? Especially with respect to racial profiling of Black, Indigenous, and people of color?

- Are we perpetuating past harms or seeking to reverse the legacy of racism transportation planning decisions?

Land Use and Mobility

The definition of travel is to go from one place to another. At first glance, highway expansions seem to be all about travel, however, by ignoring place, highway models and systems fail by being solely focused on movement. Induced demand means we get a lot less movement for our treasure than most traffic models would lead us to believe and highways are actively pushing us further and further apart while becoming barriers to movement themselves that require expensive remedies (see: the very long Northgate pedestrian bridge). A new model must consider how our land use system connects to our transportation system. Destinations that are further apart create expensive car dependence while denser neighborhoods support transit and provide the option to walk, bike, or roll.

Land use and mobility are questions a holistic model should answer when considering a transportation investment:

- Will it lead to lower vehicle miles traveled (VMT)?

- If your city, county, and/or state’s climate plan calls for lowering VMT, can this project justify planning for more VMT?

- Will it empower people to walk, bike, roll, and ride transit safely and efficiently?

- Does the land use and zoning nearby suggest the transportation project will support equitable growth or will it enrich existing landowners without providing opportunities for people looking to move to the area and find healthy, livable housing?

- What else could be done with the land taken by highways, their sprawling intersections and the wider and wider roads they demand?

Climate and Environmental Impact

Transportation is a climate issue. In Washington State personal cars and trucks moving freight account for 45% of the climate emissions emitted in the state. Ignoring for now the carbon dioxide emitted in building the highways and the cars that support a car dependent transportation system — or the forests chewed into by the sprawl it supports — a maybe too simple but illuminating equation can be written to relate transportation investments to climate change emissions.

Total CO2 Emissions = P x T x D x ((fcar x alphaco2) + ((1 – fcar) x alphaother))

P – Population

T – Trips per capita

D – Average trip distance

fcar – Fraction trips by car

alphacar – CO2 emitted per mile car (data)

alphaother – CO2 emitted per mile other

Here, to get the total CO2 emissions from a simplified transportation system, the total people population in your transportation system (P) is multiplied by the trips per person (T) and the average distance per trip (D). To get the rest of the way we multiply the fraction of the trips that are made by car (fcar), and the CO2 emission per mile by your average car (alphacar). The remainder of trips (1 – fcar) are made in some other way and given a different emission per mile (alphaother). For our purposes here we will assume alphaother is approximately zero and sadly ignore our walking, biking, rolling, bus, and train trips.

In addition, we will account for induced demand by making the fraction of car trips a function of lane miles. Here we can borrow some concrete numbers from a study by the Rocky Mountain Institute that shows increasing lane miles leads to increasing driving (increased fcar) and increased carbon emissions. For example, using the University of California Davis model for induced demand set to San Francisco — adding a 100 lane miles induces 773.1 million additional VMT. At 0.466 tons of greenhouse gases emitted per 1000 VMT (to borrow from similar analysis done down the highway in Portland) that is an additional 0.36 million tons of greenhouse gases emitted a year (for context, all of Washington State currently emits 99.6 million tons of greenhouse gasses per year).

Very few of these values are fixed, but this equation serves to show how the whole system drives CO2 emissions and how we might change those emissions. For example, when people live closer to the places they want to be both their trip distance and trips by car go down and reduce the vehicle miles traveled (see average vehicle miles traveled in Seattle (~6,000 miles/year/person) vs. King County (~8,400 miles/year/person). In addition to density (which reduces energy use on its own), investments in sidewalks increase walking, investment in safe bike infrastructure increases biking, same for frequent bus networks, light rail, and commuter rail. Build it and they will come. This kind of induced demand (more safe options → more trips) might increase both total trips per capita but will also steal trips from the car trips, making a higher fraction of trips that have much less CO2 emissions per mile.

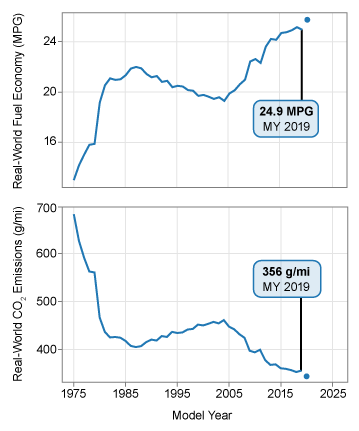

Finally, and in a paragraph all its own, electric cars. Increased adoption of electric cars and trucks has the potential to reduce the average CO2 emitted per car trip (alphacar) and thus reduce the overall emissions from the transportation system. The more miles driven that are powered by electrons the better (for the climate — the weight and particulates of electric cars are still a problem for energy use, human and ecosystem health, and road maintenance). However, though the roll out of more electric vehicles is promising for greenhouse gas emissions, we have a long way left to go. Electric vehicles currently make up 50,000 of 8,042,128 vehicles registered in Washington (0.625%), while the increased size of combustion engine cars has actually taken overall efficiency in the wrong direction.

Estimates abound for how fast we can get electric cars on the road in significant numbers (reducing alphacar) but increasing vehicle miles traveled will be taking us in the wrong direction. Nine hundred residents of King County switching from a combustion engine to an electric one (costing residents $45 million in new electric vehicles, expensive solution as has been noted) is equivalent to avoiding (or removing) just one lane mile of highway using the University or California Davis calculator set to San Francisco (conservatively saving residents $8 million of highway expansion per the University of California Davis calculator as above).

This suggests that we must approach this with a ‘yes and’ approach to types of mobility (except combustion cars, these gotta go). However, the size of the electrification mountain we have to climb (and the subsequent reduction in CO2 emissions) is very dependent on the type of transportation system (including all of the above considerations) we invest in. Given the costs and additional benefits of (at least) not inducing more driving, living closer together, and alternate modes of travel — if you care about climate you should care about vehicle miles traveled.

Environmental questions a holistic model should answer when considering a transportation investment:

- Will it increase total trips by high carbon dioxide emitting modes of travel?

- Will it decrease the amount of trips taken by low to no carbon dioxide emitting modes of travel?

- Will it reduce the distance of high carbon dioxide emitting trips?

- Will it increase noise and particulate emissions that damage nearby wildlife and people?

Cost and Jobs

For better and for worse, highway projects are very expensive but this also means that they employ a lot of people building and maintaining them. However, this money doesn’t come from nowhere and every dollar spent is an opportunity cost to employ people doing something else that provides more mobility and public benefit. Data shows that investments in public transportation actually create 70% more jobs per public dollar spent expanding highways. This is before even considering the benefits of investing the billions it takes to expand a lane of highway ($110 billion for one more I-5 lane from Oregon to British Columbia in each direction) in something that provides affordable housing close to amenities (investment needed for affordable housing) avoiding the need for more highway capacity all together. If we can get more jobs and a more successful transportation system for less money — that leaves more money for other priorities.

Economic questions a holistic model should answer when considering a transportation investment:

- What investments beyond roads can provide the same (or better) utility to the transportation system?

- What investments provide more and more stable employment?

- What other costs are required to support the mobility investment (e.g., enforcement and first responders)?

Support for a new model

Existing traffic models, while rarely effective at predicting the future, are deeply ingrained into the transportation engineering and planning progressions. It won’t be easy to get the industry to embrace a new way, especially when highway building is also a political apparatus with a built-in lobbying machine that unites business, labor, car enthusiasts, and leaders of both major parties. Nonetheless, that is the task before us if we are to meet our state’s ambitious climate goals. Reaching net-zero by 2050 won’t happen without making bold changes.

A daunting task though it may be, there’s also evidence support for a more holistic approach to transportation and land use is picking up steam. The Washington State Legislature, pressured by Futurewise-led coalition that included The Urbanist, passed major Growth Management Act (GMA) reform for the first time since passage. The goal is to promote a diversity of housing types with dense infill housing added to the existing mix which is heavy on single-family zones in developed cities and to require cities to plan for affordable housing. While it may sound like a minor commonsense tweak, considering how land use planning has been done in our state for decades, it’s a sea change.

Imagine if transportation planning also had a requirement to truly plan for a diversity of users, not just people who own a car. Imagine if transportation engineering and planning also require us to advance our equity and racial justice goals. Imagine if transportation projects were required to be aligned with the climate action plans in that jurisdiction and demonstrate that they further those goals in order to get funding. Many jurisdictions have identified the need to lower VMT, including King County’s goal of trimming VMT 20% by 2030. In 2008, the Washington State Legislature set the goal of halving per capita VMT by 2050. Few have set about reorienting their transportation system to match VMT reduction goals. King County and Washington state continue to plan for more cars, not less.

A new model can’t win all these fights for us single-handedly, but it can give us a powerful tool and jumpstart the shifting paradigms. Regardless of if a more holistic model is adopted, it’s clear the old endless VMT growth model must be relegated to the dustbin of history. If transportation planners chase pseudo-science into climate catastrophe and environmental ruin, they’ll have no one to blame but themselves and their conventions. Once we hop off the highway-building hamster wheel, we’ll have so many more resources for better investments. And at least we won’t be going in circles.