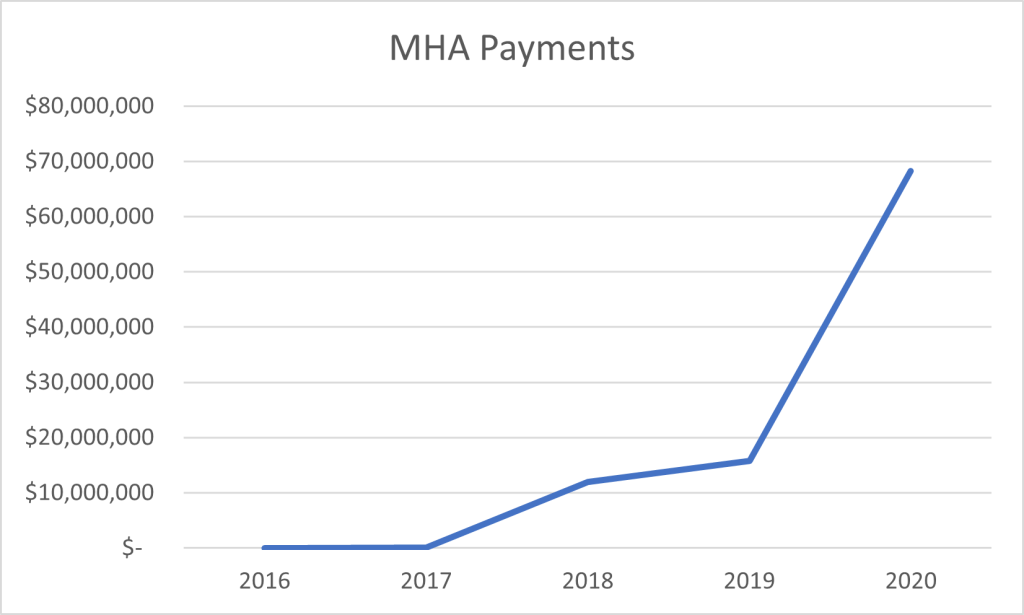

Last week the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program celebrated two years of being in effect in all multifamily areas of the city. The data thus far suggests the program is largely working as intended and on pace to hit its goal of producing at least 6,000 affordable homes in a decade.

The Seattle Office of Housing (OH) dropped a bevy of annual reports earlier this month among them was a report on MHA production.

In March 2019, the City Council passed MHA rezones in 27 urban villages across the city and Mayor Jenny Durkan signed the legislation into law. The Council passed an earlier wave of MHA rezones in the University District, Downtown, South Lake Union, Uptown, and the Central District over the course of 2017, which triggered the inclusionary zoning program sooner in those neighborhoods. However, the “citywide” program was delayed a year and a half by a series of appeals from a coalition of homeowner groups dubbed the Seattle Coalition for Affordability, Livability, and Equity (SCALE). The MHA rezones touched only 6% of single family zones, leaving roughly 75% of residential land still set aside for single family homes — albeit with an accessory dwelling unit (ADU) or two.

The rezones typically added one or two stories of building height in exchange for affordability requirements ranging from 5% to 7% of homes in “M” zones and up to 7% to 11% in the highest intensity “M2” zones where the increases in building heights and allowed densities are much more pronounced. Developers can also pay an opt-out fee calibrated to create an equal or greater amount of housing than the percentage requirement, but at another site. Those in-lieu fees go into the City’s affordable housing trust fund and the Office of Housing adds them to its annual housing investment awards.

Thus far, developers have overwhelmingly chosen the in-lieu fee option rather than performing on-site, with only 104 units on-site so far. The influx in MHA revenues is helping the Office of Housing to ramp up its annual awards, which in turn pushed affordable housing builders to boost production, too.

In 2020, MHA fees contributed $52.3 million of Seattle OH’s record award of $115.9 million in annual housing investments. The previous high was $110 million in 2019. All together “1,286 new affordable rental apartments will be produced through those awards,” the City said. Based on the funding ratio, 580 of those apartments should be credited to MHA. OH’s other major funding source at $56.7 million in 2020 was the Seattle Housing Levy, which voters approved in 2016 and is due for renewal in 2023.

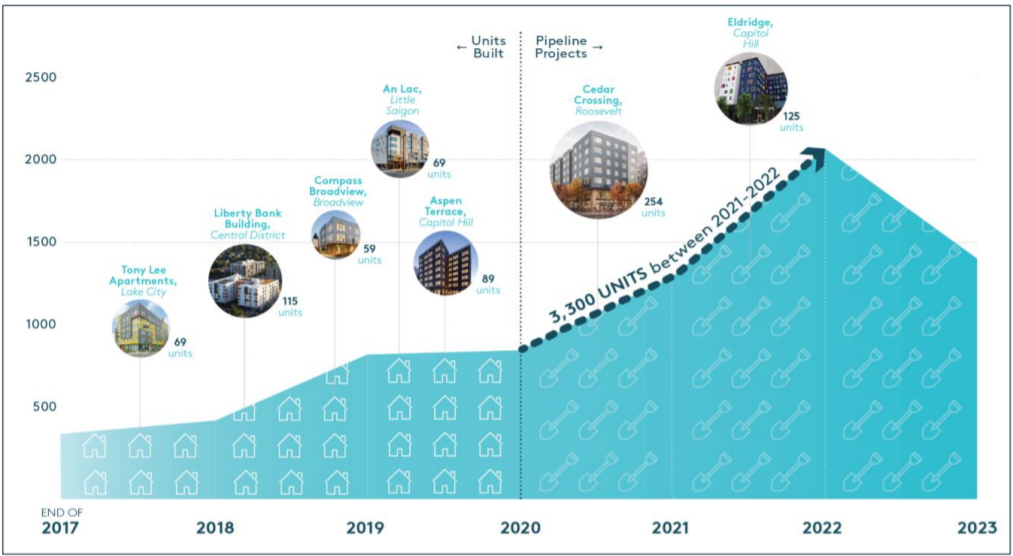

The OH is expecting the pace of production to only increase and is projecting 4,600 affordable apartment units will be completed between 2021 and 2023.

“Through investments over the past 39 years, Seattle now has over 19,000 City-funded rental housing units in operation (14,400) or under development (4,700). In addition, over 1,050 homebuyers have purchased their first home with an affordable City-funded loan and 300 permanently affordable homes are in service or under development with City assistance. Approximately 2,400 new City-funded affordable units opened to new low-income renters between 2017 and the end of 2020 – with 825 of those units commencing lease-up in 2020 alone,” Seattle Office of Housing said in its Annual Investments Report.

Housing production holding steady

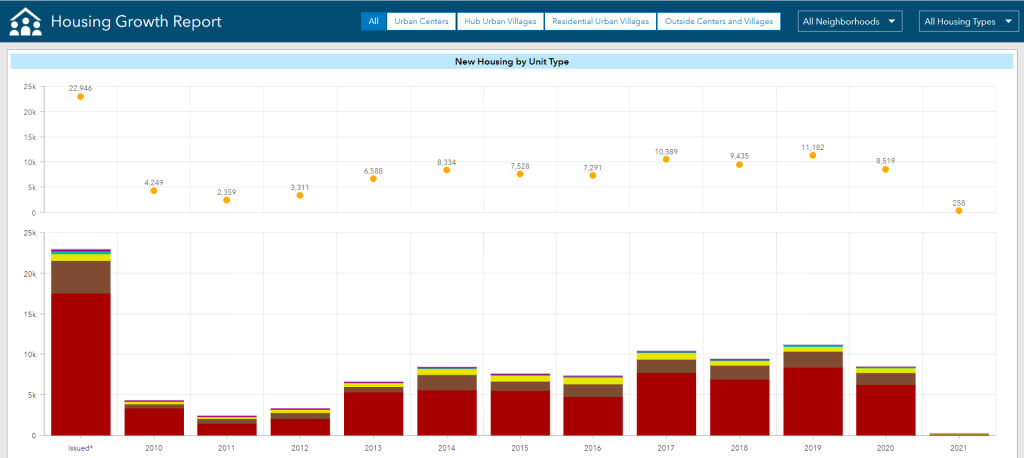

Kevin Schofield of SCC Insight analyzed permitting data from the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) last week and found housing production was holding steady. “MHA seems to have made no significant impact on multifamily housing development in Seattle,” he wrote. “Of course, nothing else has either: since mid-2019 both the number and size of the multifamily projects being applied for has grown, but neither is reflected in the permits being issued.”

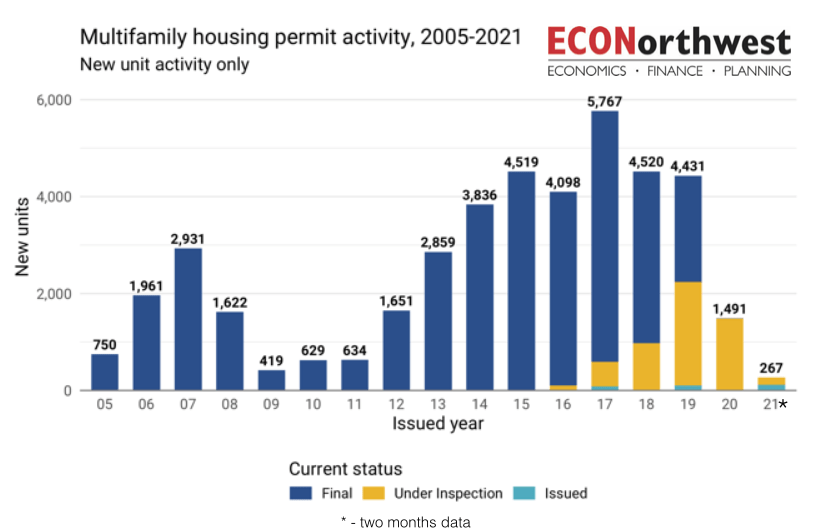

While in some cases developers did appear to race to get their projects vested under pre-MHA zoning to avoid contributing fees or affordable units, overall that phenomenon wasn’t strong enough to lead to a significant slackening of overall housing production in the wake of MHA. Given the development cycle, 2019 may already have been queued up to be a big year, but developers racing to beat MHA requirements may have helped push the total up to 11,182 homes produced.

In contrast, Portland observed a big building blitz ahead of its inclusionary zoning ordinance followed by a sharp dip in permitting that lead to critics assailing the program as the culprit. Cities should be open to fine-tuning the program, especially if it’s clearly obstructing development. Portland is seeing a metro-wide construction slowdown; thus, inclusionary zoning may not necessarily be the primary drag on production since surrounding suburbs didn’t pass a program. Portland’s regional slowdown could mean that the race to beat inclusionary zoning requirements may take longer to absorb than in the hotter markets like Seattle. Developers have also complained about the rent stabilization program that the Oregon state legislature passed. New rentals are exempt from rent controls for their first 15 years, which suggests a capital strike may be at play rather than pure economics. Moreover, part of Portland’s issue seems to be that their inclusionary zoning program exempts projects of 20 units or fewer, which has encouraged developers to just build smaller projects, even bundled together as shown below.

Seattle’s program exempts single family zones, but every project benefitting from an MHA rezone triggers the affordability requirement. If Portland continues to see development gravitating toward projects under 20 units, they may want to rethink their design.

Overall, multifamily permitting activity is down 66% in Portland city limits and down 42% in Seattle, according to ECON Northwest’s analysis of HUD data. Even in fast-growing Salt Lake City, which doesn’t have an inclusionary zoning program (but is considering enacting one) permitting activity is down 26%, while Denver is down 22%. On the other hand, Sacramento (+89%), Austin (+52%), and Nashville (+34%) are cities where permitting activity is picking up, ECON Northwest reports.

Dip in office development

Schofield highlighted that commercial permitting activity had plummeted after a banner year in 2017. This is negatively affecting both MHA contributions and City revenue overall, since sales tax and real estate excise tax are major revenue sources in a city lacking an income tax or capital gains tax.

“Between 2016 and 2020, the annual count of new construction permits was fairly consistently between 260 and 350; however, the total value of those permits dropped dramatically starting in 2019: from over $3 billion in 2017 to under $700 million in 2019 and 2020.”

The per square foot MHA fees for office development are lower than for residential. Still, plenty of large office projects slipped their permits in and vested before MHA went in effect. The biggest of the bunch was the 58-story Rainier Square, which is just now coming online with 720,000 square feet of Grade A office space, plus high-end hotel rooms and apartments. The 44-story F5 Tower opened in May 2017, and 38-story 2+U Tower (now christened Qualtrics Tower after its anchor tenant) opened in late 2019, each adding a similar amount of office space. Plus, Amazon’s 38-story “re:Invent” tower opened in 2019 with 1.1 million square feet.

Amazon is the largest employer in Seattle, with about 50,000 of 75,000 employees in the Seattle region based in the center city. However, Amazon has said it will focus regional office jobs in Bellevue going forward, partially as a rebuke of Seattle for passing a payroll tax hitting them and not being grateful enough or electing its preferred City Council candidates. Amazon adding more jobs in Bellevue rather Seattle is another reason why permitting is slowing west of Lake Washington. However, it may be a bit of a moot point on housing growth long-term, particularly once East Link light rail opens in 2023, because workers may choose to commute to Bellevue from elsewhere since the Clay City’s housing market is even pricier than Seattle’s and affordability efforts haven’t been very aggressive.

Slowdown in townhome development

While Seattle’s housing production is hanging in there, some sectors are lagging and a long drought in permitting activity could dry up the pipeline and cause prices to shoot back up and displacement pressure to jump. Townhome permitting activity has dropped recently, and developers like Marco Lowe have pointed to MHA as the drag here. Rents are down in Seattle during the pandemic, but the market for single family homes is incredibly hot, which is linked to people wanting to upgrade for more space while they’re working from home. Townhomes and small co-op or condo buildings could help ease this market pressure, which is why the drop in activity is a little surprising.

Lowe works for the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish counties (MBAKS) and is also a developer of small apartment buildings himself. I toured Lowe’s Beacon Hill small efficiency project last month and talked to him about his experiences as a developer and will follow up soon with an article based on what he and other builders are saying is happening to their projects in low-rise zones.

Potential fixes include streamlining permitting and design approvals for smaller projects to decrease risk for developers, reforming single family zoning to allow townhome projects all across the city, boosting the density bonus, and/or payment plans for smaller projects so they don’t need to pay MHA fees upfront.

On the whole, MHA is allowing Seattle to pick up the pace of social housing production closer to where it needs to be, which is welcome news. This bump shouldn’t lead us to get complacent. We could improve our housing outlook further by taking MHA truly citywide, investing more in social housing, jettisoning predatory delay mechanisms, and fine-tuning the program if certain zones continue to see little to no development after the economy is humming along once more.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.