The Seattle City Council is contemplating issuing bonds for $75 million to be spent on bridge maintenance projects instead of funding $80 million in safe streets maintenance and improvement projects over the next two decades. Even for people who like that tradeoff, the catch is that Seattle’s bridge funding shortfall can be measured in the billions, making this gutsy bonding maneuver still a drop in the bucket. Plus, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) Director Sam Zimbabwe told the council that the agency doesn’t have shovel-ready bridge projects just yet and suggested a steady drip might be better than receiving all of the maintenance money upfront followed by a twenty-year drought while bonds are repaid.

Transportation Chair Alex Pedersen, the lead author of the bridge bonding proposal, waived away Zimbabwe’s concerns and continued on his quixotic quest to solve the bridge maintenance backlog in nickel and dime fashion — those nickels and dimes coming invariably from bike and pedestrian infrastructure and transit. Pedersen spoke of federal matching funds and favorable interest rates, but his plan still entails about $40 million in debt service costs and uncertain prospects with federal grant awards.

It’s a tiny band-aid on a gaping wound, but what would a real fix look like? The discussion among councilmembers suggested some were looking ahead to renewing the transportation levy in 2024 and anticipating that as the main funding opportunity to really address the City’s maintenance backlog. Let’s look at the transportation levy and some other alternative funding sources that may be able to handle the heavy lift.

The levy option

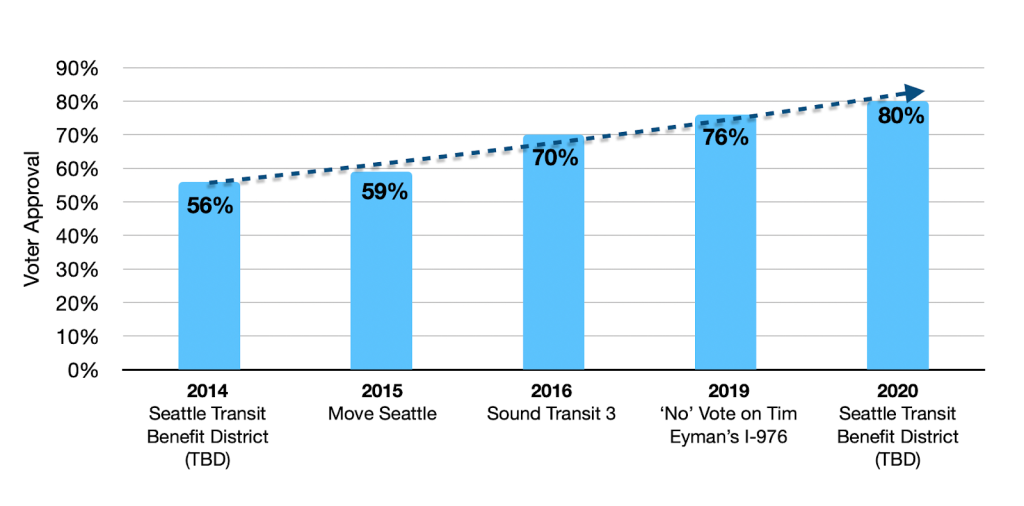

The nine-year Move Seattle levy passed comfortably in 2015 with 59% of the vote. Since the renewal is due in 2024, the levy approach also has a timing question. With President Biden rallying to pass his $2.25 trillion jobs plan, the next four years could offer unique opportunities for federal support for infrastructure projects and waiting until 2024 could risk missing out. Still, the levy is the largest obvious funding opportunity on the horizon for SDOT and provides a substantial portion of its budget.

The $930 million Move Seattle levy hasn’t stretched that far considering it was tasked with basically doing it all, from Lander Street Overpass bridge to pothole repair to bridge maintenance to “intelligent” traffic signals to a major buildout of RapidRide lines, protected bike networks, safe routes to school, and new sidewalks. Move Seattle has ended up falling short of several of its promises, shelving four planned RapidRide lines and delaying promised bike lanes.

The preceding Bridging the Gap levy also had a spread-too-thin problem. That $365 million transportation levy also authorized a commercial parking tax and an employee hours tax that were expected to generate an additional $179 million — though the City Council rescinded the employee hours tax hoping to stimulate job growth during the Great Recession. The City Council had pulled back from an earlier $1.1 billion levy proposal to put the smaller version on the ballot instead. Given the 53% support for the $365 million version, that may have been prudent electoral decision, even if it did kick the can down the road.

On the other hand, the lukewarm support arguably could have been tied to an overemphasis on maintenance over new mobility options like added transit service or pedestrian infrastructure. The City promised “Transit and Major Projects” 15% of the levy but delivered only 10% based on its 2015 report. Bike and pedestrian infrastructure was promised 18% and got it. Maintenance was promised 67% and got 72%. Move Seattle placed greater emphasis on street safety and transit and passed by a more comfortable margin.

Given the trend of transit measures getting stronger and stronger support in Seattle, the authors of the next transportation levy would be wise to make transit a focal point. But if there several billion dollars in bridge maintenance needs, that threatens to subsume the levy even if City funds are matched by the federal and state governments. Voters might not look at a maintenance package as favorably as one centered around transit, walkability, and safety given recent ballot measure results.

But how big would the measure need to be to avoid the stretching too thin problem that has undermined implementation of the last two transportation levies? And will a significant jump in state and federal aid really be in the offing?

How much bridge money is enough?

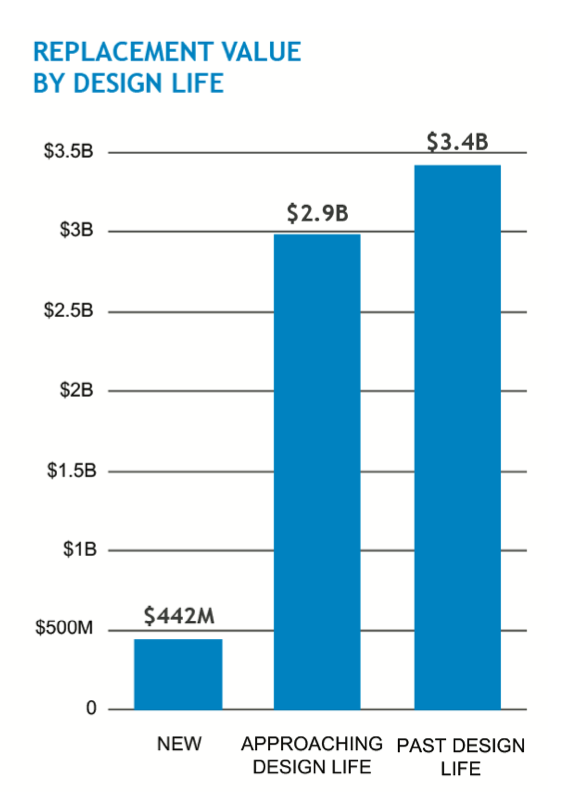

Councilmember Pedersen seems to have namedropped every major City-owned bridge in town in his maintenance and replacement crusade, but to act on this scale would take a massive investment.

- $34 million to $102 million per year in ongoing bridge maintenance needs according to the City Auditor;

- $1.5 billion high-end estimate for a mid-level replacement of the Ballard Bridge (built for 20% more car capacity);

- $420 million high-end estimate (2018 dollars) for a 1:1 replacement of the Magnolia Bridge, which District 7 Councilmember Andrew Lewis has endorsed.

- Hundreds of millions to upgrade or replace the University Bridge;

- Hundreds of millions for the 2nd Avenue Extension Bridge;

- Hundreds of millions for replacing 4th Avenue bridges near new Chinatown light rail station.

Over a decade, we’d be talking $3 billion or more just in bridge costs, which doesn’t account for everything else a transportation levy should cover. Assuming the City manages to leverage its bridge investments 3:1, that’s still $1 billion from the City to cover its perceived bridge needs. The levy still would need to fund road maintenance, arterial repaving, transit upgrades, court-mandated curb cuts to meet Americans with Disability Act (ADA) standards, and safe streets improvements like sidewalks, protected bike lanes, and protected intersections. Even a two-billion-dollar levy would be stretched thin without getting bridge costs under control.

A guiding vision

So many competing projects compels us to strategically prioritize needs and aligning investments with a long-term transportation vision for Seattle. This is exactly what Transportation Chair Pedersen has not done. Rather than planning for the future he’s continued to plod along with antiquated paradigms, just as traffic engineers envisioned ever-increasing traffic volumes when they proposed supercharging the Ballard Bridge and its freeway style interchanges.

If we instead imagine and seriously plan for weaning ourselves off car dependencies and carbon intensive travel, we’d be planning slimmer roads and bridges with bus lanes, bike lanes, and wide sidewalks becoming routine rather than the rare exception. We’d forget about a 1:1 for replacement for the Magnolia Bridge, which serves a neighborhood of about 20,000 people with a third bridge for little reason other than this is the way it’s always been done (an Armory Way alternative, by the way, would cost half as much while offering better multimodal connections.) We’d discard freeway style interchanges for the Ballard Bridge and focus on walkability and safety in the corridor instead.

The Urbanist Editorial Board laid out this principle of downsizing bridges last year. By overbuilding roads and bridges, we create the next generation’s backbreaking maintenance backlog. We funneling more cars onto bridges, we also increase the wear and tear on them, which seems to have more to do with the West Seattle Bridge’s failure than a lack of maintenance funding. It’s a hamster wheel and we can’t seem to stop exhausting ourselves chasing the tantalizing but illusory cheese that is level of service for cars. Let’s get smarter.

Alternative funding strategies

Seattle overreliance on the transportation levy to solve every transportation problem is part of the issue. Other options are out there, and having a wider variety of revenue streams could be a big asset.

- Parking tax and fees – Harkening back to Bridging the Gap, Seattle could jack up commercial parking tax (currently at 12.5%) and add parking meters across the city. The downside is this could be a volatile funding source, sagging as parking garages are redeveloped, cratering in economic downturns, and/or dipping as people switch to riding transit, biking, walking, or ridehailing.

- Payroll tax – One progressive revenue source the City has access to is a payroll tax, but the nexus may be stronger with housing. JumpStart Seattle enacted a progressive payroll tax on large companies last year. The City could increase the tax, but likely won’t want to kick up the big business hornet’s nest again so soon.

- Income tax – One positive outcome of the Trump-Proof Seattle tax, which was struck down in court, was establishing that Seattle has the right to pass a 1% income tax. Again there would be competing needs for this revenue stream, and bridge maintenance may have a hard time outshining some others, whether municipal broadband, social housing, or some other Green New Deal style program.

- Road pricing – Mayor Durkan briefly glommed onto the idea of road pricing and studied the idea of putting a cordon toll around Downtown Seattle. She has since distanced herself from the proposal, but road pricing could generate significant transportation revenue, decreasing road pollution and climate pollution, and better manage road demand to lessen congestion. The nexus would be stronger with bridge maintenance, but the idea is politically fraught and both the Durkan administration and Transportation Choices Coalition have insisted that road pricing would have to go to the ballot first, even though the statutes don’t seem to require a public vote.

- Impact fees – Transportation impact fees are a favorite of Councilmember Pedersen’s, but it’s not clear they could raise the kind of money needed for expensive bridge overhauls without suffocating development. If enacted, revenues would be more wisely applied on cost-efficient projects like sidewalks, protected intersections, and bike networks. It’s also a volatile funding source tied to development cycles.

- State package funding local bridges. – The state has invested billions in highways, but has mostly funded state routes rather than local ones. With cities and counties across the state grappling with maintenance backlogs akin to Seattle’s, the state would be wise to focus on fixing bridges and roads first (whether state-owned or local) before adding and expanding new highways. Are they likely to do that? Probably not as long as Steve Hobbs runs the senate transportation committee. Still, it’s worth a shot next session as the legislature once again takes up a transportation package hoping the fourth time is the charm.

Of the bunch, road pricing seems the best fit for bridge funding, but in all cases Seattle has more needs than it has revenue sources. The key factor will be right-sizing our bridges so we are not rebuilding our backlog and over-investing in the wrong priorities that take us farther from our climate goals. Our elected leaders owe Seattle a bridge plan that future generations can afford.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.