Leslie Kern teaches feminist geography, but she is under no illusion that straightforward solutions can magically cure the imbalance and violence baked into our cities.

“No amount of lighting is going abolish the patriarchy,” she writes, pointing to research from feminist geographers Hille Koskela and Rachel Pain revealing that widened walkways and improved lighting failed to significantly increase feelings of safety. She observed her students “get really discouraged or annoyed” when they realize there is no easy fix to unequal access and safety in the public realm.

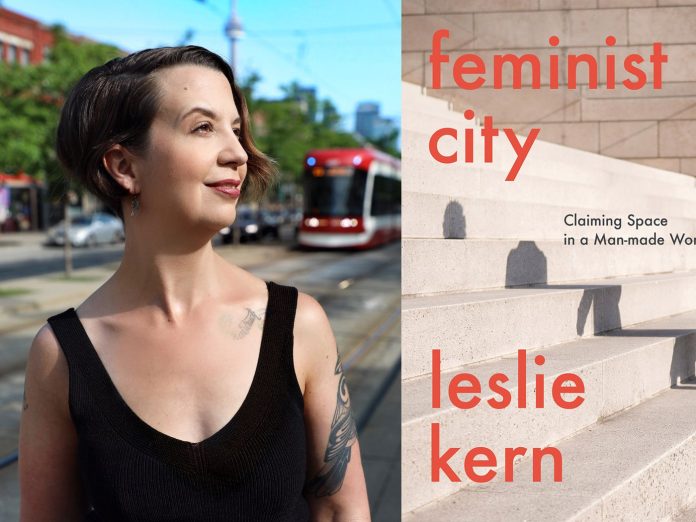

Kern’s book Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-made World, however, attempts to offer deeper solutions and lay out a vision of a city that empowers everyone and overcomes the pigeonholing default of cities as playgrounds for wealthy men. Her policy suggestions go beyond urban design to deep structural reforms across cities. The book follows her early formative experiences in Toronto and London, and later raising a kid in cities not designed with mothers and children in mind.

The city through a woman’s eyes

Through research and Kern’s own autobiography woven into the book, Feminist City carefully dissects how women experience cities differently than men. For cis-gendered men like myself this can offer some important reminders and wake-up calls and aid in the process of checking male privileges and sharpening conceptions of an utopia in the urbanist mold.

The stark reality is that White men dominate the spheres of architecture, urban planning, and policymaking. As an example, Kern highlighted a cover story in the University of Toronto magazine (the school is Kern’s alma mater) titled The Cities We Need that included four articles, each written by middle-aged White man, an identity that influenced which other urbanist thinkers they cited.

“Most of the experts cited by the authors were men, including the ubiquitous Richard Florida, whose outsized influence on urban policy around the world through his (self-confessed) deeply-flawed creative class paradigm might in fact to be blame for many of the current affordability problems plaguing cities like Vancouver, Toronto, and San Francisco.”

This cover story is hardly an outlier. The influence of Florida and other White men like Andrés Duany, Peter Calthorpe, Jeff Speck, and Charles Marohn on urban planning is colossal and clearly the prevalence of this White male perspective causes some ideas and people to be overlooked, while overemphasizing others. Kern notes feminist Sara Ahmed dubbed this phenomenon citationality: “White men cite other White men: it is what they have always done… White as a well-trodden path; the more we tread that way the more we go that way.”

Nonetheless, Kern stresses the deep history of women writing about urbanism and urban life, citing Charlotte Brontë, Jane Addams, Ida B. Wells, Catharine Beecher, and Melusina Fay Peirce.

Moreover, women can lay a strong claim of needing the urban amenities and convenience cities offer more than men can. “As early as the 1980s, my own future PhD supervisor boldly claimed ‘a woman’s place is in the city.’ Gerda Wekerle was arguing that only dense, service-rich urban environments could support women’s ‘double-days’ of paid and unpaid work.” In contrast the “nightmare of suburban living” offered social isolation and long commutes just to do routine errands.

Paradoxically, cities are also unwelcoming places for women and transgender people given the risk of sexual harassment and violence. “Male power and privilege are upheld by keeping women’s movements limited and their ability to access different spaces constrained,” Kern wrote. “As feminist geographer Jane Darke says in one of my favorite quotes, ‘Any settlement is an inscription in space of the social relations in the society that built it…. Our cities are patriarchy written in stone, brick, glass and concrete.‘”

Transit and sidewalks not maintained for the needs of parents with strollers and kids in tow is one example of how that patriarchy (and ableism) is written into stone, as is the lack of affordable family-sized housing and the scarcity of childcare centers.

“Every aspect of public transit reminded me that I wasn’t the ideal imagined user,” Kern wrote. “Stairs, revolving doors, turnstiles, no space for strollers, broken elevators and escalators, rude comments, glares: all of those told me that the city wasn’t designed with parents and children in mind.” That in turn led to her revelation that she had overlooked challenges disabled people face in accessing transit as well.

Unprotected bike lanes, disjointed sidewalk networks, and unsafe pedestrian crossings make walking, rolling, biking, or jogging a white-knuckle experience and another example where a daredevil man or a person in a car is the imagined user, rather than a woman or a disabled person.

Cities and safety nets

Perceived fear of crime and danger is often divorced from the actual risk of crime, Kern notes, but the threat of violence still greatly affects how women experience urban spaces. Part of the issue arises in how fear of dangerous men is displaced into places.

“Fear of crime surveys ask participants who they fear, and for women the answer is always men. But men as a group can’t practically be avoided,” Kern writes. “Women’s fear of men takes on a geographic logic. We figure which places to avoid, rather than which people. Feminist geographer Gill Valentine explains this is one way of coping with a constant state of fear: ‘women can’t be fearful of all men all the time, therefore in order to maintain an illusion of control over their safety they need to know where and when they may encourage ‘dangerous men’ in order to avoid them.'”

This urban geography reflects then reflects the socialization and experiences of the individual. “For women of colour, who report higher levels of harassment and violence than white women, white men and male authority figures such as police officers may be especially worrisome,” Kern wrote. “But since we have very little control over the presence of men in our environments, and can’t function in a state of constant fright, we displace some of our fear onto spaces: city streets, alleyways, subway platforms, darkened sidewalks.”

Part of the fear is driven by the real worry that police are not effective protectors, do not take women seriously, and perpetuate the myth that women who experience rape and sexual assault were “asking for it.” Women have fought back with Slutwalks focused on dispelling that myth. “They remind the public that rape culture is pervasive, and that the police have usually done more to uphold rape culture than to challenge it,” Kern wrote.

Kern underscores the importance of friendship between women to overcome the obstacles cities present and thrive. “We took each to the hospital after falls, bike crashes, and stomach bugs. We kept each other safe, and even more, helped each other learn to take up space, to fight back, to be ourselves despite the constant reminders about how we were supposed to look or behave. My friends were my safety net, my city survival toolkit,” Kern writes. “Being with my friends helped me to challenge deeply-ingrained unconscious belief I should take up very little room, physically, emotionally, verbally. They helped me to direct my frustrations onto schools, systems, and structures rather than other women, and to feel strong and less afraid. Female friendship, in short, was more than a life raft: it was power.”

The theme of female friendship (though historically sidelined) is increasingly reflected in pop culture with shows like Broad City and Issa Rae’s Insecure, Kern noted.

City as protest

“Some places just seem to have the spirit of resistance built right into them, where long histories of protests have saturated communities even as demographics of those communities have changed,” Kern wrote. “This was how Chicago’s Lower West Side was described to me when I visited the neighborhoods of Pilsen and Little Village to do research on environmental justice activism and resistance to gentrification.”

Those neighborhoods hosted numerous strikes and radical labor activism, including seminal events like the Haymarket Riots and the Battle of Halsted Street Viaduct. But gentrification and displacement pressure are threatening to change that as higher income creative class types encroach on these working class communities of color.

Many cities have neighborhoods where resistance “was not only in their blood, but also in the bricks and mortar of their communities,” Kern argued. New York City’s Tompkins Square is one of places, launching the Occupy Movement. In Seattle, Cal Anderson Park have surely entered this pantheon after a string of protests that highlighted the issue of police brutality and accountability, briefly led police to abandon a precinct and tolerate a pedestrianized autonomous zone. This movement pressured City Council to divert 18% of the Seattle Police Department budget outside of the department, some of it toward community-based safety and equity-focused investments.

Kern discussed the importance of intersectionality, the Black Lives Matter movement, and ensuring feminist and LGBTQ rights movements aren’t centered on wealthy White people. She recounted in 2016 when “Black Lives Matter Toronto (BLM TO) brought the massive Pride Parade to a grinding halt for 30 minutes” raising the critique that “Pride was a corporate, white-washed space, one that ignored the ongoing marginalization of the most vulnerable members of the community in return for mainstream support from the city, corporations, and organizations like the police and military.” The counterprotest of BLM TO activists and Indigenous drummers refused to budge until the head of Pride agreed to the list of demands; the most controversial demand was a ban on police marching in uniform and carrying guns at the parade.

“BLM is one of the fiercest examples of intersectional urban movement organizing going,” Kern added. “Started by three women in the wake of the murder of Trayvon Martin, BLM recognizes the deep interconnections among issues like gendered housing insecurity, gentrification, domestic violence, poverty, racism, and police brutality.” Kern did a whole chapter on protest because “I’ve learned that a feminist city is one you have to willing to fight for.” She also noted that James Baldwin, as a queer Black man, was regularly harassed by police on the same Greenwich Village streets that inspired Jane Jacobs to write about delightful diversity and the ballet of a busy city sidewalk.

Creating a feminist city

Feminists have long offered ways to improve how we organize cities, but many of those recommendations have not been implemented at scale, particularly in North America. “Visions of the ‘non-sexist city’ often centre housing issues, noting that the nuclear family home is a really inefficient way to utilize labour, one that keeps women tied to the home with little time or energy for other pursuits.” Building affordable family-sized housing in sufficient quantities ran into the buzz saw of austerity regimes that the neoliberal era ushered in during the 1980s.

Feminist housing designs have emphasized shared common areas and on-site day care to promote social bonding and lessen the burden of childrearing on women, Kern notes, but with the North American governments pulling back from social housing creation, that kind of housing was rarely built.

As in many things urban, Vienna is a shining example of a different way, as it adopted a “gender mainstreaming” approach. The City of Vienna surveyed residents in 1999 and found “vast discrepancies between men’s and women’s use of city services and spaces,” Kern wrote. “Vienna attempted to meet this challenge by redesigning areas to facilitate pedestrian mobility and accessibility as well as improving public transport services. The city also created housing developments of the sort imagined by feminist designers, including on-site childcare, health services, and access to transit.”

Gender mainstreaming has a longer history and greater adoption in Europe. Some cities even used the approach to rethink their snow plowing strategy. “In most cases, cities plow major roads leading to the central city first, leaving residential streets, sidewalks, and school zones until last,” Kern wrote. “In contrast, cities like Stockholm have adopted a ‘gender equal plowing strategy’ that instead prioritizes sidewalks, bike paths, bus lanes, and day car zones in recognition of the fact that women, children, and seniors are more likely to walk, bike, or use mass transit. Moreover, since kids need to be dropped off before work begins, it makes sense to clear these routes earlier.” The strategy has the added benefit of encouraging people to use active transportation rather than drive.

Kern also highlights where gender mainstreaming can run amuck by reinforcing existing gender norms and roles around paid and unpaid work. She cites the example of Seoul where “high heel friendly” pavements and “pink” parking spots designated for women have been rolled out, but not serious efforts to equalize or subsidize domestic and childcare labor.

Riffing on Jane Jacobs-esque scenes Kern concludes: “We need to set aside the rose-coloured glasses and notice who is missing from that picture of idealized city life. Where do we begin? For one, the faces of urban planning, politics, and architecture have to change. A wider range of lived experience needs to be represented among those who make the decisions that have enormous effects on people’s everyday lives. An intersectional analysis must be a common approach to decisions big and small: where to place a new elementary school, how far apart bus stops will be, whether small businesses can be operated out of comes, etc… Planning to improve safety for women can’t reproduce carceral models that target poor people and people of colour.”

All in all, Kern has created an excellent field guide to feminist urban geography and creating a feminist city. Not all of the proposed policy solutions are sharp breaks from the progressive urbanism canon, but they could offer superior ways to frame and mobilize around them.

Thanks to Verso Books for a review copy of the book. You can order Feminist City on the Verso Books website or your preferred bookseller.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.