Getting urbanism right is a big reason Jessyn Farrell is running for Mayor of Seattle.

“In an era where we’re reckoning with systemic racism and fifty years of growing income equality, we really need to show the way where cities can continue to be an excellent way of organizing ourselves, Farrell said. “From a climate perspective it’s more carbon efficient. There’s more resiliency. From an economic vitality perspective, density and ability to exchange ideas and commerce, that all really matters, but there are a lot of ways the city is really failing right now.”

Housing affordability is a central theme in her campaign.

“And the core question for me and that really animated me is: Is this going to a city we want to live in and can afford to live in?”

Farrell has called for a “ST3 for housing” in her platform. Sound Transit 3 was the ambitious $54 billion transit package passed in 2016 that will add several new light rail and bus rapid transit lines and extensions totaling about 60 stations. Farrell doesn’t have a proposal fleshed out, though she said to expect a housing plan in coming weeks. However, the implication of her vision would be to go bigger than we have before.

As a former Transportation Choices Coalition executive director, Farrell led the campaign for Sound Transit 2 (ST2) back in 2008. Elected to the state legislature representing Northeast Seattle in the 46th District, Farrell helped write the ST3 authorizing legislation that paved the way for the rapid transit package (literally in this case since it had to get added to $13 billion worth of highway projects to pass both chambers). With authorization granted from the state, Sound Transit ran the ST3 ballot measure in 2016 and it passed with 54% of the vote within the taxing district. Farrell left the legislature to run for Mayor of Seattle in 2017. She finished fourth with 12.5% of the primary vote. For more on Farrell’s background, check out our earlier announcement writeup.

Open streets and safe routes

Another attention-grabbing Farrell proposal has been to create a 100-mile network of open streets. This would build on the 20 miles of permanent Stay Healthy Streets that Mayor Jenny Durkan rolled out during the pandemic, promised to make permanent, but hasn’t yet delivered on funding. Safe Routes to School is a very popular program, Farrell noted, and could be used as a way to organize and advocate for a rapid buildout of the open street network.

“If we went really robust quickly around rapidly funding those safe routes projects across the city, maybe really focusing on those communities that are farthest from educational justice and have historically been left out of transportation investments, that I think is one way to frame it that people already embrace,” Farrell said.

Safe routes to parks, business districts, and health care could offer other ways to prioritize routes and look to build the open street network.

“One thing families have experienced in Covid is the freedom of not having to drive kids around,” Farrell said. Those trips ferrying kids to school and activities burden parents’ schedules and contribute significantly to traffic congestion, accounting for upwards of a quarter of trips at peak times. She pointed out the benefits of safe routes to school, activity centers, business districts, and health care would have to this problem.

“The safe routes idea and expanding that to parks and activity centers allows kids to have more freedom and agency in getting to where they want to go,” Farrell said. “And then you can build on that framing, which is to say that anyone in the city should have agency and mobility freedom, particularly if you’re at the older or younger end of the spectrum or are disabled.”

“Obviously we’ll be re-upping the Move Seattle Levy.”

Like other candidates, Farrell is hoping for funding assistance from the Biden administration, but she appeared quicker to promise a renewal of the Move Seattle Levy and outline a plan than some of her opponents.

“The place I would start looking because I’m opportunistic and know how this works is the Biden administration and working quickly with the Congressional delegation to get funding in place as it is going through an infrastructure discussion,” Farrell said. “Obviously, we’ll be re-upping the Move Seattle Levy, and using the next couple of years to identify what the top priorities for these ‘safe routes to’ and then fill in the blank. But with a real aim at the goals of increased transportation agency and freedom and then also real trip reduction so that we’re getting to realize our carbon reduction goals.”

Farrell offered a two-part strategy to pass the next transportation levy and make sure that it is implemented better than Move Seattle was, which has most of its promised RapidRide bus lines shelved and several key bike projects delayed or shelved.

“That visionary piece is really, really important and people respond to that, but the second is the relentless dedication then to implementing what gets funded,” Farrell said. “And that is where there have been some problems with the Move Seattle Levy. That is about having people in place at the agencies who are laser-like focused on implementing, recognizing that public support is opened up when there is strong implementation, and people can see oh look my tax dollars are actually resulting in this sidewalk or this bike lane or this light rail station.”

Farrell talked about accountability and setting goal management principles as mayor and then empowering the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) to take the ball and run with it. She also said: “There’s good people at SDOT, full stop” and stopped short of saying a shakeup in managers and top executives is needed.

Farrell saw Mayor Durkan’s decision to cancel the safety-focused redesign of 35th Avenue NE and swap in a car-centric design as a clear mistake. “That was not my vision,” she said. “The way the pavement is currently allocated is not an efficient use of street space for anybody, and it’s almost the worst of all possible worlds as a transportation solution.”

Police accountability and narrowed scope

While she hasn’t promised to reduce the Seattle Police Department budget, Farrell supported reducing the scope of their work, mentioning make fares free and ending fare enforcement on transit, repealing the law against jaywalking, and using automatic camera enforcement rather than a police officer for the transportation laws we do want to enforce. Fare-free transit was one of the things the pandemic showed was possible, and that we must fight to bring back, Farrell said. Though in a city with high transit ridership like Seattle, that could require a significant funding lift.

Farrell criticized the 2018 contract with the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) for removing police accountability measures. She credited I-940 and state legislation moving ahead this session for creating better avenues of accountability for police misconduct, limiting arbitration and ability for police to overrule discipline.

Overtime spending is one area she’d look to tighten up and trim costs, she said, as would decreasing the number of armed officers responding to situations, such as the mental health crisis that ended up leading to police killing Charleena Lyles.

ST3 for housing

Zoning changes are a piece of her ST3 for Housing plan, but not the be-all end-all for her.

“The discussions around zoning and planning are really important and they are certainly one piece of the puzzle, but we have to be much more comprehensive about what we are trying to achieve from an affordability standpoint,” Farrell said. “That’s why I’m proposing what I call ST3 for housing, which is to say a robust, regional comprehensive focus on housing — and again not just the zoning but the financing mechanisms, the infrastructure supports that go around it, and a commitment to housing diversity…”

Farrell pointed to racist housing policy as a justification for investment in social housing. She talked about federally subsidized 30-year fixed mortgage creating stability for homeowners, and noted the lack of a program to guarantee housing stability or offer a similar level of investment for tenants. Since the federally-backed mortgages weren’t initially offered to Black, Indigenous and people of color, that program left them behind, as did segregated public housing projects, sometimes used as slum clearance mechanisms.

Farrell stressed a desire to promote community land trusts and affordable accessory dwelling units (ADUs). It’s not yet clear just how that would work, but she suggested the Mayor could play a role as a convener and send a clear signal to the financial community to invest in ADUs. The housing plan she’s promising later this month should have more details.

“I’m supportive of more housing and reforming our zoning so that we are creating more housing. Period. But you don’t get the outcome you want through incentives alone,” Farrell said. “We have to be thinking about public investments that again are undergirding some of these ideas around financing, whether it’s new pathways to ownership through really strengthening and building out community land trusts, particularly around transit stations — whether it is helping some of the infrastructure costs that drive up the cost of a unit quite a bit.”

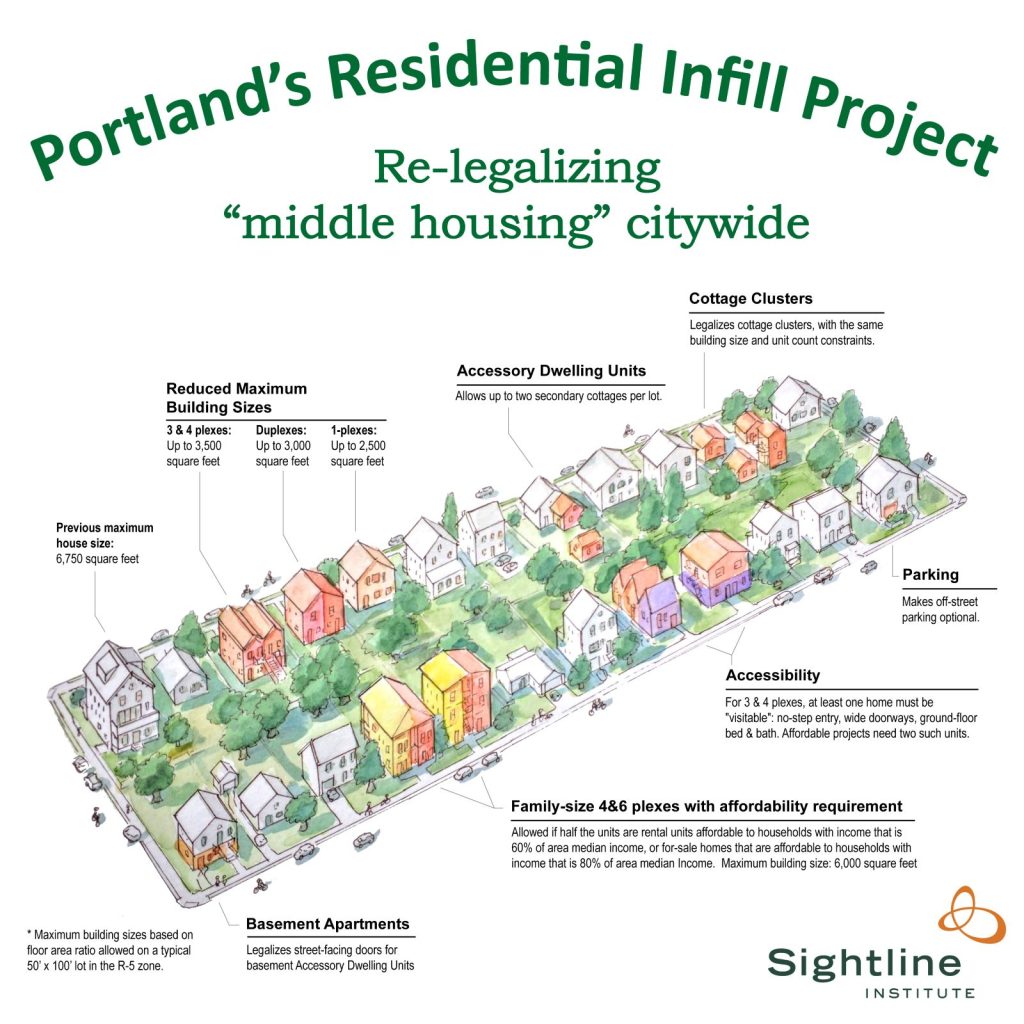

Farrell cited Portland’s affordable housing plan as a model, but it wasn’t clear if fourplex zoning with a sixplex bonus if half the units are affordable will make it into her plan.

Whether the rest of King County could be convinced to go in on a social housing funding plan also could be a sticky issue, at least based on how the lack of progress, and headwinds the Regional Homelessness Authority has faced so far.

Another comprehensive plan goal Farrell has is to ensure affordable child care and embed goals within the plan. The idea seems to build on an ordinance by Councilmember Dan Strauss, who is land use chair, allowing child care centers to be sited in single family zones. She would seek to establish universal child care from birth to age 5.

Climate plan: Green TOD, reducing car miles traveled

Farrell’s climate plan, which she said will be released in a couple weeks, starts with transportation. She said her transportation plans work toward reducing vehicle miles traveled, a key driver of emissions.

The second piece of her climate plan is driving down emissions through housing. She’d focus housing in areas best served by our transportation infrastructure, particularly adding affordable housing in transit-rich areas and building that transit-oriented development (TOD) to deep green standards. “Decarbonizing our housing stock” as she suggested would tackle the second largest source after transportation emissions.

“As mayor this will be one of my top priorities: to fundamentally transform our city’s relationship to carbon,” Farrell said. “And that is why I’m running.”

Support for Lid I-5

In describing her climate plan, Farrell mentioned lidding I-5 could further that goal by encouraging walking and biking in the downtown core and freeing up land for affordable housing. The prospecting of Lidding I-5 could get a boost if President Joe Biden succeeded in getting funding for mitigating destructive freeways in cities into his infrastructure bill.

The advocacy group Lid I-5 has been advancing planning efforts to prove the feasibility of lidding I-5 from Madison Street to Denny Way and prepare some preliminary designs. A Mayor that’s bought into the vision paired with some federal funding support could be the spark needed to realize the lid park dreams.

A crowded field

The race appears to have five major contenders, though more could establish themselves with robust media and/or fundraising presence or announce before the mid-May filing deadline.

Of these, Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda’s interim policy manager Andrew Grant Houston was the first in, announcing in early January. Colleen Echohawk joined later in the month. On February 3rd, City Council President M. Lorena González announced her mayoral run. Former City Council President Bruce Harrell hopped in on March 16th with a centrist data-heavy approach. Farrell joined two days later. Candidates, as with Farrell, are promising more policy details in coming weeks and months, but for now they are generally running on broad strokes.

From her announcement, Farrell has been critical of her opponents, suggesting that González and Harrell share blame for years of inaction by virtue of being on city council. That said, she largely offered plans that echoed or piggybacked on the City Council’s work. And when asked if she regretted voting for Mayor Durkan (who engineered or oversaw much of the inaction) over Cary Moon in the 2017 election, she deflected and said she wished she could have voted for herself. Her endorsing Shaun Scott in 2019 could at least be some consolation to the urbanists out there.

Of this crowded field, only two candidates can make it through the August 3rd Primary to the general election. The Urbanist Elections Committee will issue primary endorsements in July so watch for those to drop.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.