When Governor Jay Inslee held a press conference with Washington State Secretary of Transportation Roger Millar and other area officials at the Lake Washington Ship Canal in March, one word was emphasized: maintenance. “We need to make the investments first, and I emphasize first, in maintenance of our existing transportation system”, Inslee said, calling maintenance “woefully underfunded” in Washington.

In 2019, WSDOT estimated that there was an annual gap of $690 million between funding available for maintenance and the amount the state would need to spend to maintain a state of good repair on its state highways. This is around 20% of the department’s annual budget of $3.6 billion per year — filling that gap would mean more than doubling the amount currently spent on maintenance, around $550 million.

Neither of the two funding packages currently being discussed in the House and Senate Transportation Committees would fully close that gap despite the fact it may be the state’s last chance: if the funding levels for maintenance stay at current levels, the cost to repair the roadways later could triple. Instead, both packages would spend more on new highway projects rather than on maintaining existing ones.

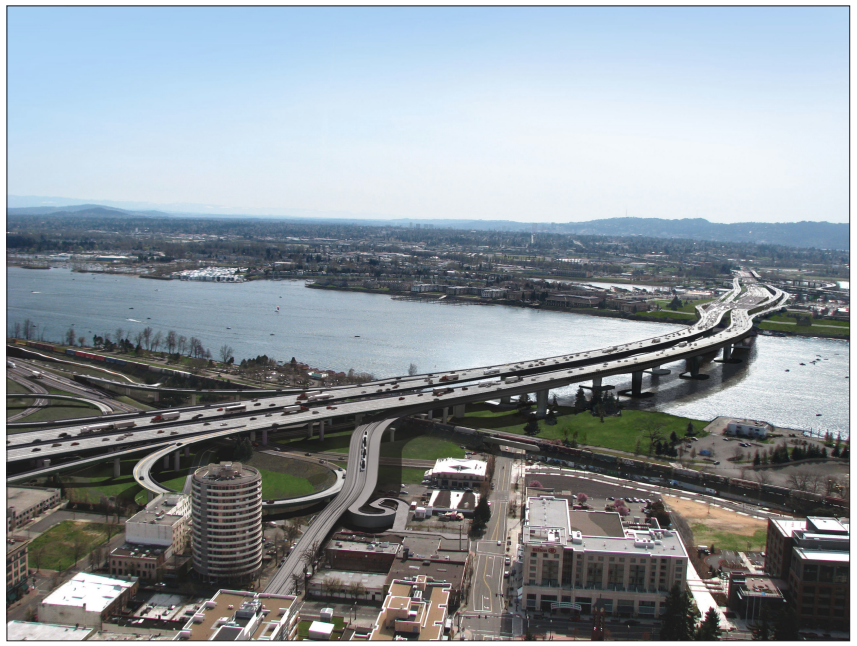

But there’s one project that both packages made sure to include: the “replacement” of the I-5 bridge between Washington and Oregon. This project continues to be lumped in with the state’s deferred maintenance backlog. But there’s actually no design for the project yet, and all signs point to a carbon copy of the failed Columbia River Crossing project which was (allegedly) cancelled in 2013. That project was far from a replacement for an aging bridge structure.

Columbia River Crossing 2.0

The Interstate Bridge Replacement, as the new iteration is called, looks like a brand new project. It has a flashy new website. New groups have been assembled to provide input into what the project will look like: an Executive Steering Group, made up of representatives of public agencies and governments around the project area; a Community Advisory Group, which includes voices for different regional interests; and the Equity Advisory Group, which includes voices who will ensure the project centers equity. But materials have noted that the project office will “leverage past work as appropriate to ensure effective and efficient decision making that includes new data and public input,” and the project team wants to work fast and get this project approved.

One reason being used to justify moving fast is the claim that $140 million in federal funds could need to be repaid if significant progress isn’t made by September of 2024. This is related to another big tether to the Columbia River Crossing: the state DOTs are relying on the federal Record of Decision issued in December of 2011 to hold the project’s spot in terms of environmental review.

This year, the advisory boards were asked to develop new Purpose and Need statements for the project, essentially setting the scope and goals before the project team started to develop the actual design. A draft purpose statement included a direct reference to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and the need statement mentioned the current inequity of transportation costs. But before that language could even be approved, the project team checked with the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) to see if those changes could get made and still allow the project to use the 2011 Record of Decision. Last month the advisory groups were told that no, they likely can’t add language on reducing greenhouse gases and addressing equity.

Greg Johnson, the administrator of the Interstate Bridge Replacement program, responded to a follow-up question from The Urbanist about the proposed changes to the program’s Purpose and Need with the following statement:

Our recent engagement efforts validated there is widespread agreement that the previously identified transportation problems still exist. Other priorities identified by stakeholders and the community included equity and climate considerations. While we are continuing to advocate for updated language in Purpose and Need, we do not yet have final direction from our federal partners regarding the extent to which we can modify language without restarting work as a new project. No matter what the outcome of that conversation is, the program is continuing its work to weave equity and climate considerations throughout the program in actionable and measurable ways.

Portland Transportation Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, a member of the Executive Steering Group, is not on board with rubber stamping the Purpose and Need developed over a decade ago. “Climate and equity are two of the most urgent needs of our time. And I would still like to see these centered with the Purpose and Need for this project…relying on the same framework as the CRC is not serving us well today,” she said at an ESG meeting earlier this year.

Oregon Metro Council’s President (and former WSDOT Secretary) Lynn Peterson also appears to be another voice on the ESG pushing back, saying, “We’re getting to the point where it’s starting to sound like the old way of doing business, and I don’t want to slide into that.” Currently the schedule calls for the project to finalize new Purpose and Need statements by the end of May.

Very Far from a Replacement Project

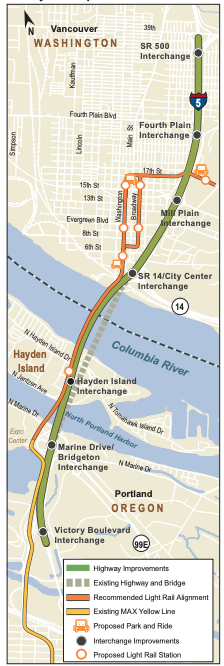

The fact that the project is trying to reuse the 2011 Record of Decision makes clear that the project is not a replacement project. The purpose of the Columbia River Crossing project, according to that document, was to “improve I-5 corridor mobility by addressing present and future travel demand and mobility needs in the CRC Bridge Influence Area (BIA)”. The Bridge Influence Area extends way beyond the segment of I-5 over the Columbia, and the CRC included expansions to seven highway interchanges on either side of the river: Victory Boulevard, Marine Drive, Hayden Island, SR-14, Mill Plain, Fourth Plain and SR-500. It even extended to improvements to the local street network around those interchanges.

The number of lanes planned for I-5 itself is another instance where the project would expand capacity in the guise of replacement. The CRC design showed two additional lanes in each direction on the main bridge span, going from six to ten. But a bit further south on I-5, the Oregon Department of Transportation’s current project to expand the freeway in Portland’s Rose Quarter has been shown (thanks to records requests filed by advocates) to include space for even more lanes than the project’s initial plans appeared to suggest. We have yet to see how updated traffic volume forecasts will impact this project’s size, and even that should be taken with a grain of salt.

Again, there is no project yet, but a conceptual finance plan presented to lawmakers last year showed estimates for the Columbia River Crossing with a fresh coat of Interstate Bridge Replacement paint were as high as $4.81 billion. The Washington legislature is set to earmark at least $1 billion if a transportation package is able to pass both chambers by the end of the session this month.

That’s $1 billion that’s set to be invested in expansion over maintenance, over safety, over multimodal access for the approximately 25% of Washingtonians who don’t even have access to a car. The conventional wisdom is that replacing the I-5 bridge is the prudent and responsible thing to do, except this project uses that as an excuse to accomplish goals that aren’t related to maintaining infrastructure at all. Don’t get fooled by the name: the IBR is a highway expansion project and should be treated as such.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.