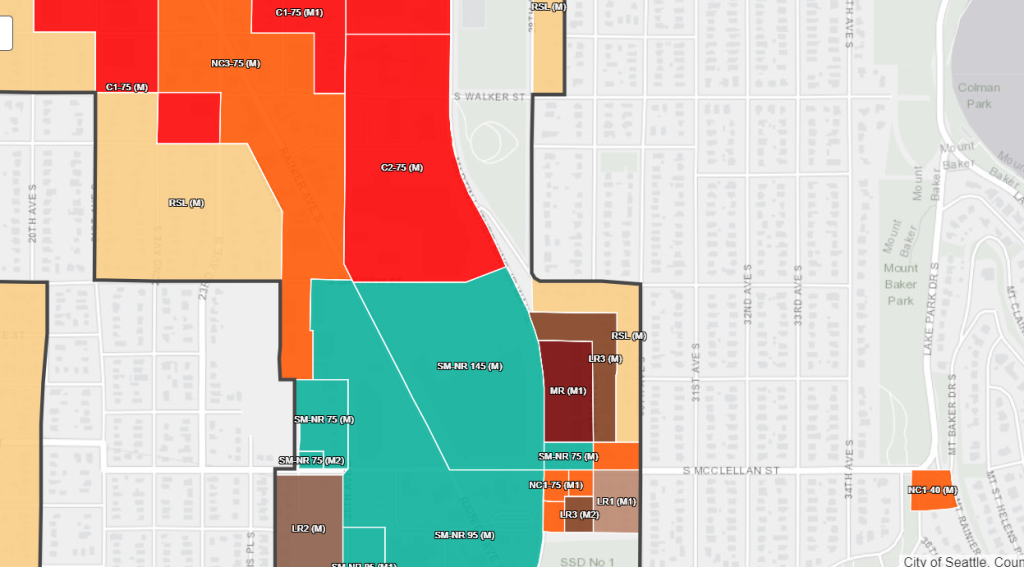

Amazon is planning a distribution center at a coveted site in Mount Baker, Brian Miller of the Daily Journal of Commerce reported Tuesday. Despite zoning allowing 145-foot towers and top notch transit that includes nearby access to Mount Baker Station, plans envision a low-slung warehouse and a colossal parking lot. Simply put, this plan must be stopped. (Sign our petition here).

The plans span two sites on the east side of Rainier Avenue S — a Pepsi plant and Lowe’s superstore. The Lowe’s site alone is almost 13 acres in size and could host almost five million square feet of development built out to capacity (floor area ratio (FAR) tops out at 8.25 including bonuses for affordable housing and open space). Developed primarily as housing, this could work out to more than 4,000 apartments, many of them multi-bedroom homes next to a new open space amenity. The Pepsi site is 10 acres and zoned to 75 feet (5.5 FAR — it’s just outside the station overlay district or this would rise to 6.0), which works out to 2.4 million square feet of developable space and could add another 2,000 apartments or more. Instead of a sprawling warehouse and parking lots, these sites could be 6,000 homes housing 12,000 people or more.

The warehouse proposal is at odds the City’s comprehensive and neighborhood planning and hopes for transit-oriented development near Mount Baker Station (and also within a 15-minute walk of the soon-to-open Judkins Park Station). The City added a section about the Lowe’s site into municipal code trying to limit uses and established a station overlay district to further promote density and walkability with a midblock crossing. Warehouses are not a permitted use in the station overlay district, but Amazon must think they can get an exception. When the City chose to upzone the Lowe’s site to 145 feet — 50 feet higher than anywhere else in Mount Baker Urban Village or nearly all of South Seattle — they did so hoping somebody would actually build highrises there. Instead, the property owners (the families of David Hsiao and Leonard Tall) are trying to make a quick buck selling to Amazon at the expense of the community who lives nearby or would like to.

Disrupting safe streets plans

And the impact on the neighborhood could be severe. The City has pledged to make Mount Baker more accessible and safe for pedestrians, not less. The project is called Accessible Mount Baker after all. Adding a massive distribution center in what should be the bustling mixed-use heart of Mount Baker jeopardizes those plans and adds traffic rather than calming it. The Accessible Mount Baker vision was to “untie” the convoluted intersection of Rainier Avenue and MLK Way and shunt freight and commuter traffic onto MLK Way in order to calm Rainier Avenue and make the street a more walkable, safe, inviting place. More of a destination and less of a cut-through. Historically, Rainier Avenue has been known as the deadliest road in town, regularly competing with Aurora Avenue as the site of most deadly crashes.

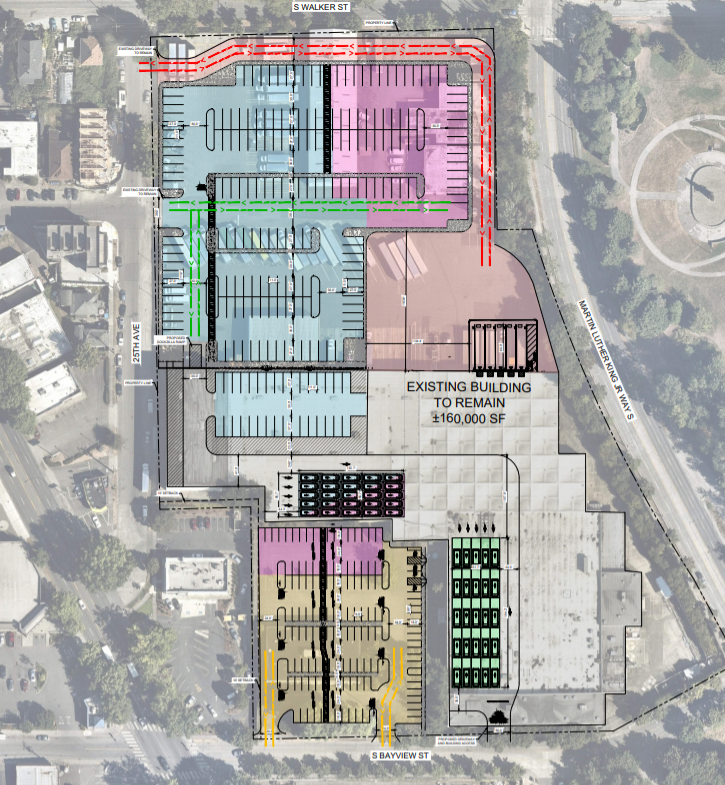

The proposal calls for a curb cut on Rainier Avenue emptying the giant parking lot onto a busy corridor with people walking, rolling, biking, and on transit trying to compete for space with motorists. Route 7 is supposed to achieve RapidRide status (eventually) and a busy trucking interchange where a bus lane should go is a terrible idea. A giant parking lot undermines efforts by safe streets advocates to improve station access to Judkins Park Station. Adding a curb cut on a major transit corridor across pedestrian overlays contradicts the Land Use Code and the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections Director Nathan Torgelson could (and should) reject this aspect of the proposal outright.

Costing us affordable housing

The undersized proposal also would cost the city in affordable housing payments via the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) inclusionary zoning program. At the sites, the residential MHA requirement is $15.36 per square foot (or 6% of the units) and the commercial is $8.29 per square foot. Seven million square feet of housing would pay $107 million into the affordable housing trust fund or add about 360 affordable homes on-site.

In contrast, Amazon’s proposal repurposes the existing building on the Pepsi site and adds a 68,000 square foot structure to the Lowe’s site. The copious surface parking is exempt from MHA and so too apparently is the structure since it can claim an industrial use rather than commercial one. Industrial uses are exempt from MHA. Thus, both of Amazon’s proposal would pays zero into MHA and would have paid just $564,000 into the affordable housing trust fund had MHA-Commercial applied. This industrial loophole, by the way, sets up a very uneven playfield where Amazon’s distribution centers are exempt from affordable housing contributions while the brick and mortar business they’re competing with would have to pay in when they develop property.

This massive underuse of the site will result is far fewer affordable homes in the neighborhood. Many urbanists are skeptical when defenders of apartment bans use buildable lands reports to argue enough housing capacity already exists, and this story is a perfect illustration of why. Capacity for thousands of homes is no sure thing, but it may still count on a buildable lands report because technically someday housing developers could build there. Tenants don’t have that kind of time to wait for more housing.

This land doesn’t come cheap either. The Pepsi site sold for $65 million three years ago. That sale price suggests the Lowe’s site would likely sell for north of $100 million given its larger size and zoning envelope. It goes to show the economic power of Amazon that they wouldn’t bat an eye buying up this valuable land mostly to store delivery vans. Amazon will argue this project brings jobs, but jobs tied to big warehouses and giant parking lots belong in the industrial areas of the city, not in an urban village steps from a light rail station. Amazon’s concurrent proposal for a four-story warehouse on Commodore Way in Interbay make far more land use sense. It’s an indictment on our industrial land use policy (and it’s long delayed update) that big box stores routinely go up in industrial zones, while warehouses are proposed in station overlay districts where 15-story residential towers should go.

Amazon boosters argued their dense South Lake Union campus shows their urbanist bonafides — and indeed it was a much better choice than that of a suburban office park. However, if Amazon wants to be seen as an urbanizing and positive influence on Seattle growth, it can’t just coast on South Lake Union. It has to walk the talk in the Rainier Valley, too. The best Amazon can do is walk away from their Lowe’s plans, allow someone to develop it as 4,000 homes (many of them affordable), and perhaps even help finance the project as part of the company’s affordable housing campaign. Conspicuously all of the announced investments have been in the Eastside thus far. This could change that.

What the City can do

But if Amazon does back away, the opportunity here is too large to squander — 23 acres next to two light rail stations and a future RapidRide is a rare commodity. The City really should step in to block the biggest sites for social housing in the Rainier Valley from being claimed as a warehouse and giant parking lot. A design review board would have good reason to kill the project, but the Pepsi plant project likely wouldn’t need to face a full design review as a renovation.

To send a clear message early, the City should do a warehouse development moratorium at the Lowe’s site (or across all station overlay districts) since the zoning intends dense mixed-use towers. That would be similar to what the City Council did with self-storage facilities in Aurora-Licton Springs or to save the Showbox. Another option would be a surface parking surcharge in station overlay areas to discourage such uses in prime light rail-adjacent real estate.

The site’s history adds another wistful dimension since it used to be publicly owned. In a different life, the site was Sick’s Stadium and hosted the Rainiers baseball club. Owner Emil Sick, who also owned the Rainiers Brewery, sold the stadium to the city in 1965, but the City in a foolish move sold it off again to be developed (circa 1977, according to Miller) rather than keep the land in public hands. It’s timely a reminder that this city could sorely use a prohibition on selling off public land to private developers.

An even more assertive option: The City could pass a right-of-first-refusal law similar to how Paris did and start lining up funds to buy the land once more and then serve as the master developer. We have to get better at seizing the opportunities in this city and building social housing as a matter of course rather than an afterthought.

Take action: Sign our petition.

Correction: This article has been updated to note that the Amazon warehouse proposals are exempt entirely from MHA payments due their use being defined as industrial rather than commercial under the municipal code.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.