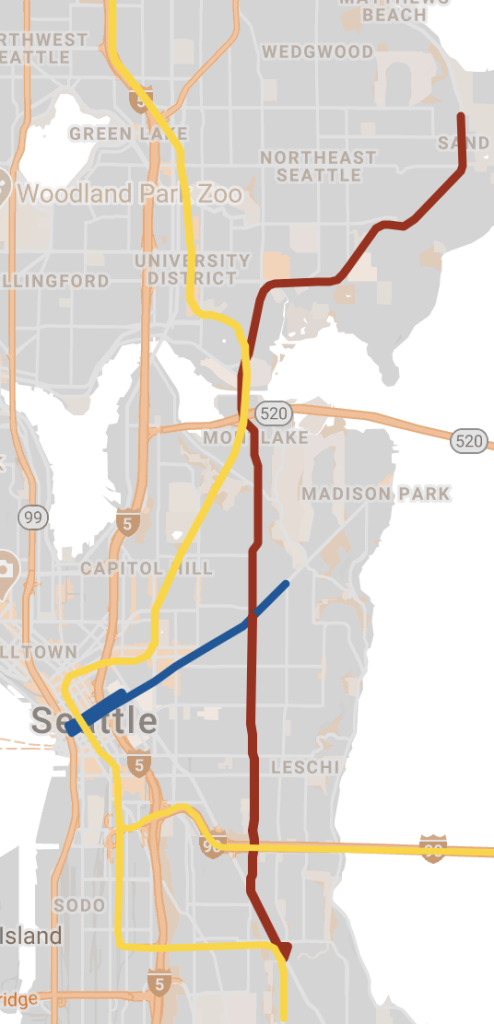

Recently, I proposed a streetcar line down Montlake Boulevard and Sand Point Way as a cheaper alternative to underground light rail expansion through Northeast Seattle. Bus rapid transit (BRT) offers another alternative, and one that could easily extend farther south. My BRT proposal essentially upgrades Route 48 — which operates from the Mount Baker Transit Center to the University District — with RapidRide+ treatment. The city promised RapidRide+ treatment to Route 48 as part of the Move Seattle Levy, and has since shelved the plan.

There would be small alteration to Route 48: instead of bending towards the University District as it currently does, it should continue down Montlake Boulevard and Sand Point Way. This would provide a rapid transit connection all the way from Magnuson Park to Mount Baker via Sand Point Way, Northeast 45th Street, Montlake Boulevard (connecting with light rail at Husky Stadium), 23rd and 24th Avenue East (connecting with the future Madison BRT line), and Rainier Avenue South — terminating at the Mount Baker Transit Center and Mount Baker light rail. Rerouting the tail of Route 48 away from the University District and towards Northeast Seattle may make the campus commute a bit less convenient, but Route 45 already provides service in that area, and the soon-to-open University District light rail station will provide even further redundant and much faster service than the current route configuration of the 48.

This proposal would deliver many of the same benefits as my streetcar proposal, but at a lower price tag per mile, and with the added benefit of connecting significantly more people to significantly more destinations and transit options. This proposal would also roll out the red carpet for bus lanes up and down most of the corridor, ensuring not just the speed and reliability of this BRT proposal, but also providing big speed boosts to numerous other bus routes that operate on different parts of the corridor.

Transit-oriented development opportunity

Building BRT throughout the designated corridor would provide the city with ample opportunities to install greater density in the area — mainly Northeast Seattle — while also improving the bike network. For instance, Sand Point Way, 23rd Ave E, and 24th Ave E all have a common characteristic as roads paralleled by low-density development alongside generally wider-than-normal lanes and an enormous percentage of street space dedicated to cars alone. This is also particularly true of the area around Mount Baker Transit Center, where big investments in good public transportation are currently primarily surrounded by gas stations, single-family housing and low density commercial space, and dangerous and car-centric streetscapes. These areas can be rezoned to create walkable, bikeable, dense, and transit oriented development with street space repurposed to get buses, bikes, and pedestrians moving safely, efficiently, and comfortably.

Building out the Accessible Mount Baker Plan, which would radically transform the area around Mount Baker Station and calm the entire Rainier corridor, should be a city priority — as should RapidRide+ treatment for Route 48. The area around the Mount Baker Transit Center is also prime space for the city to step in with publicly-owned affordable housing. Planned and existing private development in the area, alongside new public housing development, could potentially house thousands of people right next to robust public transit options, and at many different price ranges and with many different housing options.

Public housing in the area also provides the city with an opportunity to live out its own climate goals — electric heating, solar panels, passive house standards, and green roofs would set a standard for new, clean housing development in the city. Building out such housing alongside the Accessible Mount Baker Plan, a new pedestrian plaza connecting McClellan Street to the Transit Center, and the conversion of Forest Street to a shared street would create a welcoming, affordable, walkable, and eco-friendly district surrounded by great public transportation options.

Furthermore, buying up adjacent property would enable the city to find room for both bus and bike lanes on Rainier Avenue South — a small tweak I would make to the Accessible Mount Baker Plan. Currently, buses exiting the transit center often find themselves immediately clogged in traffic on the car sewer that is Rainier Avenue. Doing so would ensure the efficiency of bus routes exiting the transit center. The Accessible Mount Baker plan could do more to accommodate rapid bus transportation on Rainier Avenue. The current street space does not allow room for buses and bike lanes in any ideal way.

Ideally, the city would enact new policies to squeeze out the adjacent Lowe’s — a massive, low-density parcel right next to the transit center zoned for 145 foot buildings. The City should also act to rezone the nearby single-family zone. Zoning directly adjacent to the Mount Baker Transit Center allows for buildings of up to 95 feet tall, but just across the street sits a single-family zoned neighborhood. Further changes to this zoning will be necessary to provide the greatest bang-for-the-buck when it comes to the big transit investments the city has already made in the area.

Since 23rd Avenue was just recently rechannelized, it would make little sense for the City to create further changes to the corridor as part of this BRT proposal. Compared to much of North Seattle, the Central District has seen more than its fair share of upzones. This proposal could be built out with minimal changes to 23rd, with the exception of a few bus queue jump lanes at major intersections (like Madison Street and 23rd). A south-bound bike lane on 23rd is something the city should also consider in the future.

Designing a better transportation system

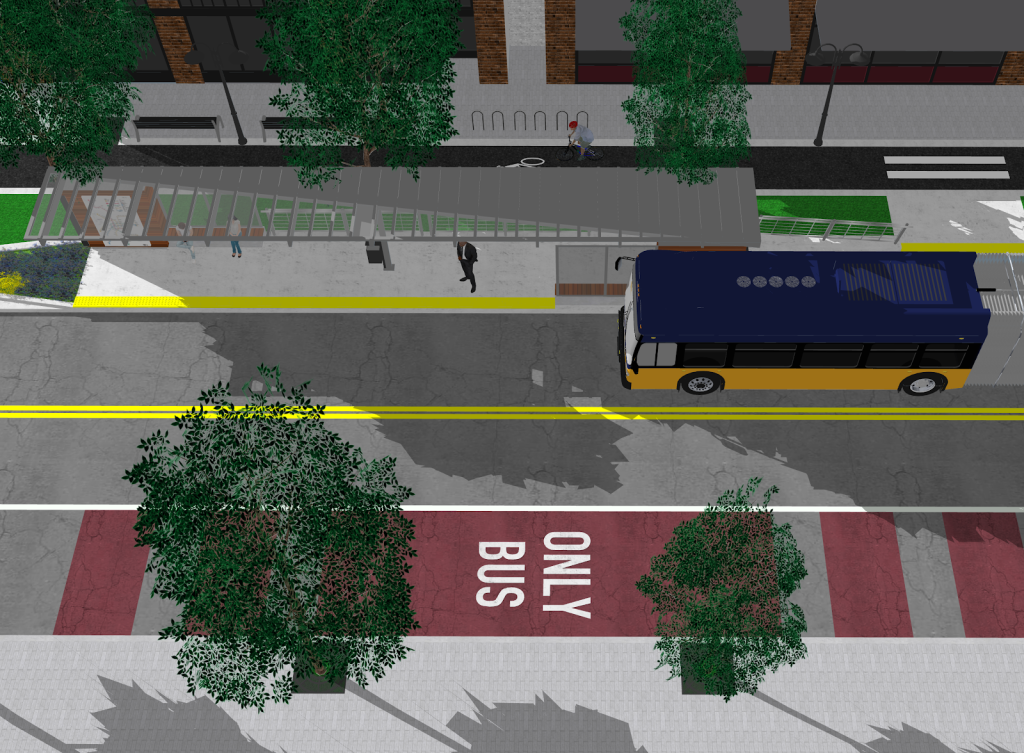

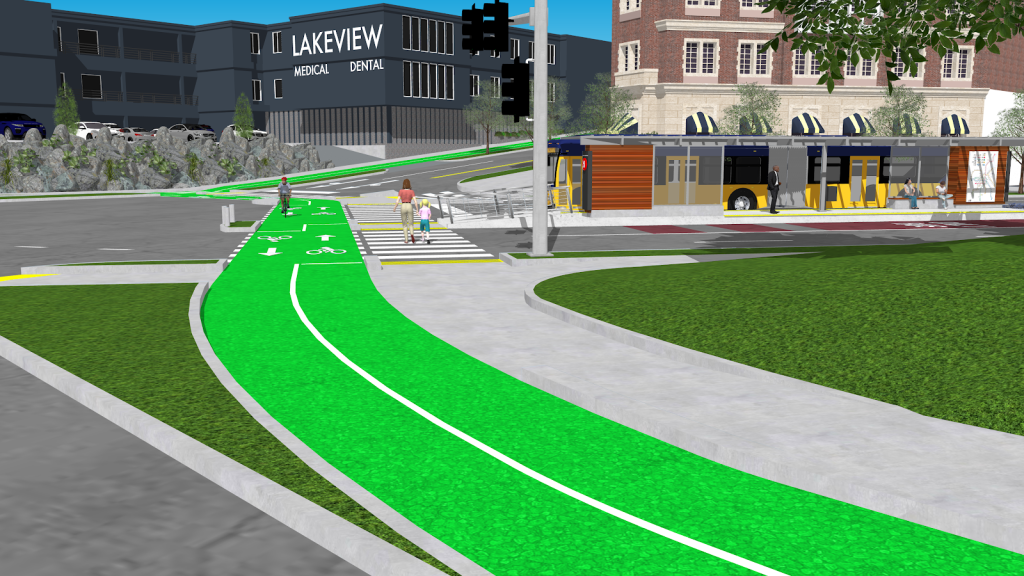

My proposal includes installing bus-only lanes through large chunks of 24th Ave E, while also providing a new south-bound, protected, and elevated bike lane on the west side of the road. This bike lane could be built out at a width of six feet, while the ample road space available could easily provide sufficient space for trees and street furniture on both sides of the bike lane, separating pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicles. Parked cars and bus stations would provide further protection, creating an extremely safe and comfortable bike and pedestrian environment. Such changes would also deliver new customers to area businesses, providing new transit options that would bring in not just drivers but also cyclists, pedestrians, and thousands of transit riders.

New bus-only lanes through the Montlake traffic mess — over SR-520 and the Montlake Cut, and down most sections of Montlake Boulevard both northbound and southbound — would get transit riders moving, while also providing an attractive alternative to drivers stuck in traffic. This would also integrate with new bus stations planned as part of WSDOT’s construction of a lid over SR-520.

While new bus stations in Montlake could be seen as exciting, a deep and unfortunate sympathy to car centrism continues to plague planning in most of the area — there’s talk of a second Montlake bascule bridge that would feature additional car lanes. Certainly, the city has built out significant improvements in the area, but almost exclusively near the light rail station on the corridor. The lack of transit infrastructure on both North 45th Street and Montlake Boulevard — bus-only lanes in particular — leaves area residents with no choice but to wait in traffic if they are to travel West or South. The city, unfortunately, has all but failed to build out bike and bus infrastructure in most of these corridors to provide a viable alternative.

New bus-only lanes down Montlake Boulevard from the intersection with Northeast Pacific Place to the intersection with Northeast 45th Street are essential to ensuring the speed and reliability of this proposed BRT line. Such lanes could be built by borrowing space from the large parking areas that parallel virtually all of this corridor. This would require the demolition of many of the bridges that cross the road, however, none of these bridges comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This would push the University of Washington to make its campus more accessible to people with disabilities. Ideally, the large adjacent parking lots would be repurposed to build a new car-free ecodistrict. This district could be filled with hundreds of square feet of greenspace, welcoming pedestrian plazas, first-floor business space, and thousands of units of student housing mixed with publicly-owned free, affordable, and middle-income housing serviced by nearby light rail and BRT.

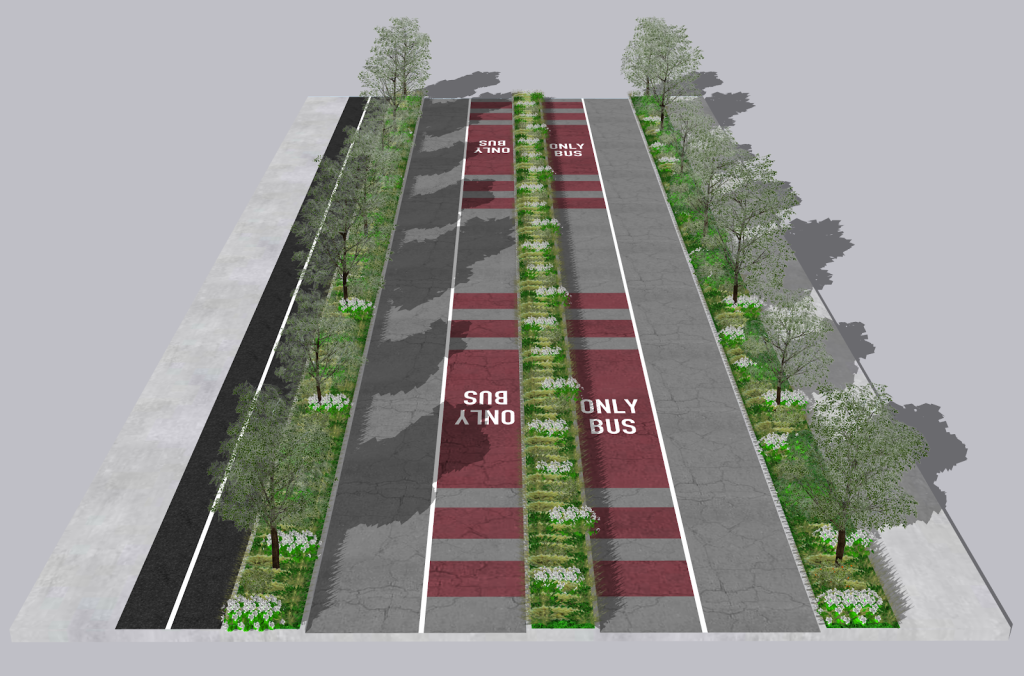

Center-running bus-only lanes would keep this proposed BRT line moving throughout the rest of the corridor, down Northeast 45th Street and Sand Point Way. The intersection of Mary Gates Way, 35th Ave NE, and Union Bay Place, however, is a major chokepoint. Signal timing that gives buses priority, as well as new bus-only lanes, are both essential. New bike lanes from the Burke-Gilman Trail down 35th and across the intersection into Laurelhurst would connect area residents and cyclists with the new bus infrastructure while also adding much-needed safety improvements at the intersection.

Buses that can accommodate boarding on both the left and right side of the bus would be necessary to accommodate the center-running lanes, albeit at a higher cost than a standard bus. However, boarding options on both sides of the bus would save on infrastructure costs by allowing the city to build stops where it’s most cost-effective, while also allowing for the greatest flexibility in road planning in such a way that bus efficiency and reliability could be maximized.

BRT on Sand Point Way would also provide an opportunity for the city to improve safety through the corridor. As I pointed out in my proposal for rail in the corridor, Sand Point Way has lanes up to 15 feet wide — highway lanes. Many places lack sidewalks, speeding is common, and safe bike infrastructure is non-existent. Building out center-running bus lanes, narrowing traffic lanes to 11 feet wide to accommodate buses and freight, investing in sidewalk infrastructure and new planting strips, and building out bike infrastructure through the corridor would greatly improve safety. Crosswalks at intersections throughout the corridor are also essential.

Making the most out of transit policy

This proposal would provide not just connections to the Madison BRT and light rail, it would also connect residents and workers to area businesses, shopping centers like University Village, hospitals like Children’s and the University of Washington Medical Center, and Magnuson Park. It would also integrate well with the Burke-Gilman trail, allowing area residents to access the new line by bike and then bus. It remains, however, pivotal that zoning changes are considered to draw in new residents and businesses along the corridor.

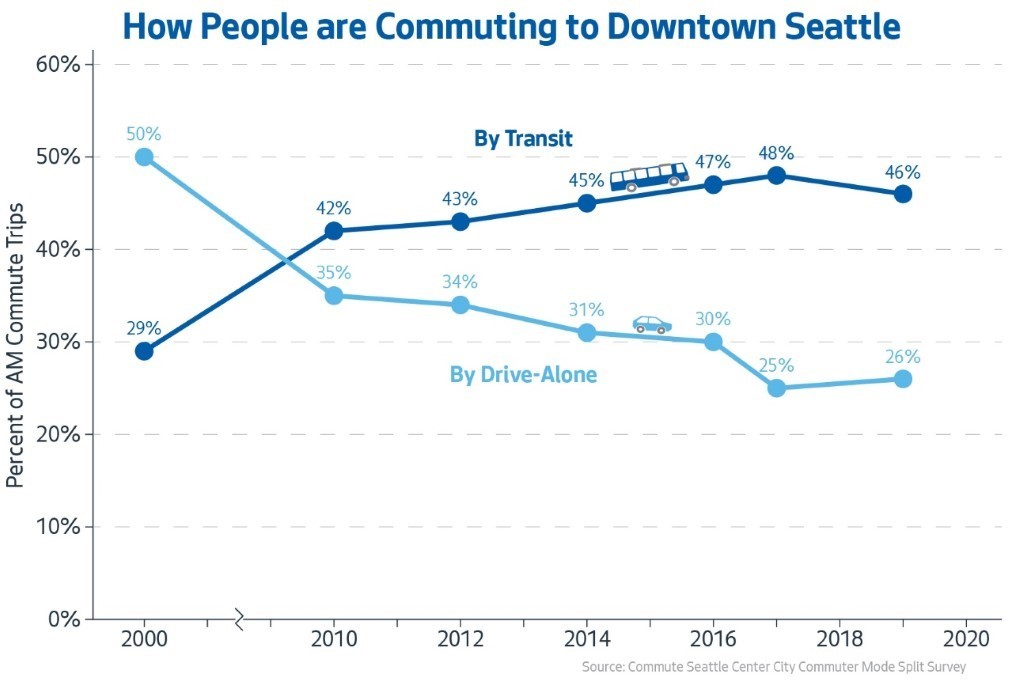

This proposal would add five miles of fast, reliable bus service from the Mount Baker Transit Center, through the Madison Valley, all the way to Magnuson Park. It would come with new bike and pedestrian infrastructure to improve safety in the area and move forward Seattle’s goal of zero traffic fatalities. It would get bus routes moving through the Montlake corridor while providing a viable alternative to driving for area residents. It would greatly reduce area traffic by moving residents from cars onto bikes and into light rail and buses. It would bring hundreds of new customers to area businesses on bike, bus, and foot. And it would come with new density along the corridor which would create new walkable, bikeable urban villages serviced by a robust transit route. This is not just a transportation solution, it is a housing, climate, and justice solution, too.

If the City of Seattle is serious about its climate goals, then we do not have time to wait to build out a robust mass transportation network. While the pandemic has punched a big hole in the city’s budget, our squelching carbon emissions, warming climate, and rising sea levels do not pause. Austerity measures put our planet, and all living things on earth, in jeopardy.

We must move, immediately, to secure additional federal funding for essential transportation infrastructure projects. Instead of cutting mass transportation projects when our climate needs them most, we could instead impose a wealth tax on the 68,000 millionaires living in King County alone. We could enact impact fees on new development or post-pandemic congestion pricing measures in downtown Seattle. We could create Local Improvement Districts (LIDs) to cover the cost of transportation projects in wealthier areas like Northeast Seattle. Our climate needs these projects, and our workers — many of whom now face unemployment — need the jobs infrastructure upgrades would provide (not austerity measures), to get back on their feet post-pandemic. There is no shortage of options available to raise the revenue we need to continue these projects.

We must also face the city’s long-time affordable housing crisis. It is essential that the city takes a hard look at the restrictive single-family zoning that blankets the city. In the face of rampant gentrification, it is imperative that the city distributes new development to the areas that can afford the costs of development — such as Northeast Seattle. And, it is critical that new density comes with publicly-owned affordable housing and a portion of below-market rate private development to provide housing for all. To take on the climate crisis, Seattle must rapidly and aggressively invest in bike lanes and mass transportation infrastructure. We must commit to new density to rein in sprawl. And we must provide housing for all. Our racist, climate-destroying, car-centric, and exclusionary single-family zoning cannot endure.

With cars alone accounting for over half of Seattle’s emissions, there is no debating that the city must move to expand frequent transit service and the bike network alongside this new density and walkability. This corridor is but one area the city should consider changes to, in order to take on the dual and intersecting crises of housing and climate. Urgent action must be taken by the city to avoid climate catastrophe and house all of our neighbors. We do not have time to waste.

Joe Mangan (Guest Contributor)

Joe Mangan is an urban studies and political science double major at Vassar College. He organized the Seattle Climate Strike, led weekly strikes outside Seattle City Hall as the founder of Fridays for Future Seattle, and was later a coordinator with the Seattle for a Green New Deal campaign. His redesign of NE 65th Street was declared “Better Than SDOT’s” by the Seattle Bike Blog.