Nikkita Oliver entered the race for Seattle City Council with instant name recognition, having finished a close third four years ago in a run for mayor. Oliver’s profile rose even farther last year during the months of protests against police brutality.

Perhaps the most iconic moment of the summer was the June 3rd march to City Hall when Oliver stood with Mayor Jenny Durkan and delivered a set of demands from a broad coalition that united under the banners of Decriminalize Seattle and King County Equity Now. The images and policy conundrums that march generated may have cemented Mayor Durkan abandoning her reelection plans.

The Mayor stood with her riot police on the steps of the City Hall looking like a nervous despot gripping to power rather than a poised and affable mayor calmly guiding an aspiring utopian city. Oliver reiterated the coalition demands to stop prosecuting (and tear gassing) protesters, halve the police department’s budget, and fund community-based health and safety. The Mayor came across as disingenuous while offering empty promises and explaining why she couldn’t pledge to stop tear gassing protesters that day. It was downhill from there for the Mayor.

“It was a very surreal moment,” Oliver said. “Standing with 12,000 people delivering a pretty clear set of demands to City Hall, I got to see what people power looks like.”

Oliver (who uses they/them pronouns) is a community organizer, cultural worker, artist, attorney, and member of the Seattle Democratic Socialists of America Afrosocialist caucus running with the backing of the Seattle People’s Party. They are executive director of Creative Justice, an art-based nonprofit specializing in restorative justice and healing youth who’ve served time in juvenile detention. Oliver organized with No New Youth Jail to oppose the creation of a new juvenile detention center on 12th Avenue. That campaign convinced the County to reduce the number of beds in the facility and commit to eventually reaching zero youth detention, but ultimately the County persisted in building the jail.

This time Oliver is running for Council Position 9, an open citywide seat vacated by Council President M. Lorena González’s run for mayor, rather than in the crowded field to replace Durkan as mayor. Their platform stresses transforming our system of community safety and justice, but it also draws a web of connections to housing justice, zoning reform, environmental justice, mobility justice, and stopping the homeless sweeps. Oliver said they want to continue the work of the 2020 rebalancing package and budget that redirected about 17% of the Seattle Police Department budget to more community-focused investments, in particular housing.

Housing for All

“We need to take money from an ineffective system and invests it in things we know not just based sociologically but based on what people with a lived experience have told us would actually help them,” Oliver said. “Housing is such a huge part of that. We often talk about issues around public safety and policing as separate from housing, but I think the lack of housing is part of the problem, and creating housing is a huge part of the solution.”

In their South Seattle Emerald interview, Oliver called for spending at least $400 million per year creating social housing, and their platform zeroes in on exclusionary zoning that is shielding much of the city from growth and limiting housing access for working class people.

“It’s no secret that Seattle has a legacy of exclusionary zoning, and our zoning has played a huge part in the problem as to why we don’t have enough housing,” Oliver said. “About 12% of the land is getting 85% of the development, and it’s happening in such a way that not only is it not developing enough housing, it’s also creating displacement in neighborhoods where people are already very much at risk.”

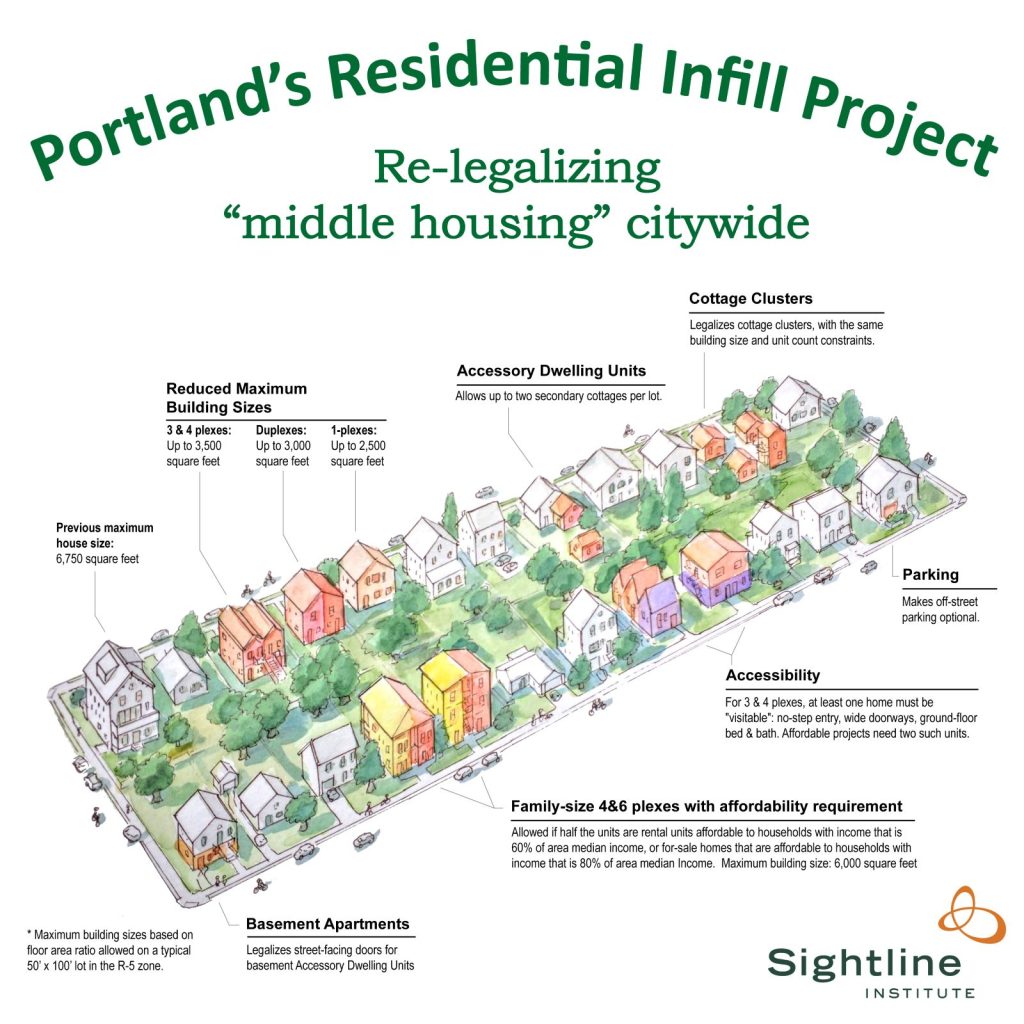

Oliver said the City shouldn’t miss the opportunity that the 2024 update to the Comprehensive Plan provides, and suggested a broad zoning reform like Portland pursued–as have cities like Minneapolis, Olympia, and Sacramento, with Berkeley and Tacoma close behind. Those reforms have sought to welcome Missing Middle Housing, like triplexes and fourplexes, in zones where only detached single family had been allowed.

“I think we could take some advice from Portland with their Residential Infill Project, which relegalized Missing Middle housing citywide,” Oliver said.

Oliver also argued for urban village expansions via the Comprehensive Plan update–which echoed The Urbanist‘s ultimately unsuccessful push to add and expand urban villages during the last major update in 2015.

“Our urban villages are very limited, so [we should be] expanding our urban villages and ensuring more parts of the city are taking on the multifamily zoning,” Oliver said. “We need a diversity of options. Our current zoning has created a bifurcated city, where two-thirds of land is not accessible for most, except for those at the highest incomes.”

Oliver pointed to community land trusts and limited equity co-ops as routes to provide wealth-building opportunities in Black, Indigenous, and people of color communities that were systematically denied access for much of our country’s history and hence have accumulated much less generational wealth.

Stop the Sweeps

While Tim Burgess and the business community are pushing more homeless sweeps and are seeking to use homelessness with a wedge issue to elect more conservative candidates, as Durkan’s campaign did as well, Oliver said that Housing First is the approach that will solve the homelessness crisis. They emphasized that Seattle hasn’t invested enough in a Housing First model since it declared a state of emergency around homelessness in 2015–the business community has impeded those investments, such as with their campaign against the 2018 head tax.

Oliver sees an irony there: “Businesses will actually do better” if Seattle invests in Housing First rather than sweeps. “The reason they feel the way they feel is the strategy we’ve invested in is ineffective,” they said. “Sweeping people that already lack stability is not only problematic, it’s inhumane during a pandemic and economic recession.”

“It’s no secret that I’m not the favorite candidate of the business community, but my interest really is in the entire community,” Oliver said. “And we’re all going to be much healthier–whether that’s folks who’ve been living outside or businesses or workers–if we actually do what it takes to provide enough housing for everyone who wants to come inside.”

Free transit, crosstown buses, and bike lanes

Oliver cited Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law to argue housing access and time spent in transit are major determinants of social mobility and prosperity. Stable housing and short commutes can be a key to unlocking opportunity, but Black and brown communities tend to have longer commutes, spottier transit, and fewer housing options. King County’s relatively expensive transit fares are also a barrier and a burden for lower income households. Oliver’s environmental justice platform starts with, “in a cosmopolitan, 21st century city, public transportation should be universal and free.”

“We’ve learned something really great during the pandemic, which is we can make transportation free,” Oliver said. “So we need to figure out how to keep that in place, because I’ve heard from so many people how that has been a major safety net for them.

The ORCA for All campaign convinced Metro to institute an income-based fare pilot in February 2020 offering free transit to low-income individuals, though the pandemic forced them to extend that to everyone shortly thereafter. King County Metro suspended fare collection starting in March 2020 as a Covid safety measure, but reinstituted fares in October. “We’ve been fighting for ORCA for all for such a long time,” Oliver said.

Oliver also pointed to adding more crosstown bus routes and protected bike lanes as priorities to rectify gaps in our transportation network and improve safety.

“Over the pandemic I’ve gotten way more into cycling and personally see not just the health benefits, but also the opportunity to not be driving my car,” Oliver said. “I also get terrified riding my bike sometimes.”

Oliver highlighted the need to renew the Move Seattle Levy, and also explain to the public why some levy campaign promises weren’t met.

“In many ways, we’ve fallen short of the goals that were in that,” Oliver said. “So I hope as a City we can offer a clear explanation for why some of those goals were not achieved so that voters have confidence to vote for the next Move Seattle Levy so that we can keep adding the infrastructure we need so our cyclists can be safe and that our children need to be walking to the buses, and our elders and our disabled community has what they need as well.”

Lowering transportation emissions, which is Seattle top source by source, is crucial to head off climate catastrophe, Oliver said, which underscores the need for investments in emission-free modes.

Defund March

In a way, Oliver’s campaign is a continuation of the organizing work from this summer–her campaign coordinator Shaun Scott also helped organize protests and advocate for police accountability, as did other campaign staff members and volunteers. Relatedly, the moment Oliver said sticks with them from the march to city hall was not on the steps with Durkan, but the teamwork that led up to it.

“When we all arrived at City Hall and we had been asked to come inside, but we didn’t just want a single set of organizers going on their own. We said we’d come if we could come with three people and live stream,” Oliver said. “And when we tried to get into city hall, the police said we weren’t allowed in that entrance. And we looked and we saw 12,000 people that we needed to make our way through to get back up the hill to 4th [Avenue], and the community acted basically as one body and made space for us to be able to walk through with ease.”

“It just felt like such a powerful showing of how much solidarity there really is around the movement to not just defund police but actually invest in communities, like Black communities and Native communities, that have been marginalized and disenfranchised historically and presently,” Oliver said. “It really was just an all around empowering moment to see 12,000 people act in concert around a shared set of demands that only been released maybe 12 hours before that rally.”

While Mayor Durkan was resistant to specific actions to redirect police funding and increase police accountability, she did glom on the rhetoric of reimagining policing and public safety. How that lofty rhetoric corresponded to policy was less clear.

“I’m not sure what they mean by reimagining policing other than, in a lot of ways, preserving the status quo,” Oliver said. “If we’ve learned anything from 2010, it’s that reforms don’t work. They require us to invest more in a failed system of policing and a failure of accountability rather than actually addressing the root cause issues.”

“The way in which I see that vision contrasting with the one that the movement has brought forward and which I hope I can be a part of bringing to City Hall is that rather than reimagining policing, we would reimagine a city that meets the basic needs of its residents,” Oliver said. “Actually taking care of people’s wellbeing promotes safety for everyone, and that is a more effective public safety model.”

Negotiating the police contract

Does Oliver imagine voting for a Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) contract, which is due for renewal? They didn’t rule it out, but laid out some specific conditions.

“If [the contract] was constructed in a way that allow us to continue the work of defunding. If it was constructed a way that we can continue to civilianize 9-1-1,” Oliver said. “If it rather than focusing on protecting officers from accountability, it focuses on protecting residents’ rights, and ensuring that when harms do occur there is a viable pathway to setting that right, including removal of officers from the force.”

Oliver said the MLK Labor Council expelling SPOG from its ranks was a welcome sign that negotiations would go differently this time and allow the City more control over how SPD’s budget is structured. At the same time when, the fact hardliner Mike Solan is SPOG President did give them cause for concern.

“Mike Solan has shown himself to believe that policing as institution is not just working fine, but great and that officers are ‘under attack.’ I do not think he’s going to bargain in good faith with the interest of protecting the rights of community members,” Oliver said. “It is going to be a considerable fight.”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.