In 2018, Mayor Jenny Durkan made a splash by embracing the idea of enacting downtown cordon tolling to reduce car congestion, pledging to realize the scheme in her first term. On Tuesday, reporting from KUOW confirmed her administration was no longer pursuing that plan. In its place, they are offering an “electrification blueprint” that hopes to accelerate the pace of electric vehicle adoption and establish an emissions-free zone by 2030, though details and a funding plan are lacking.

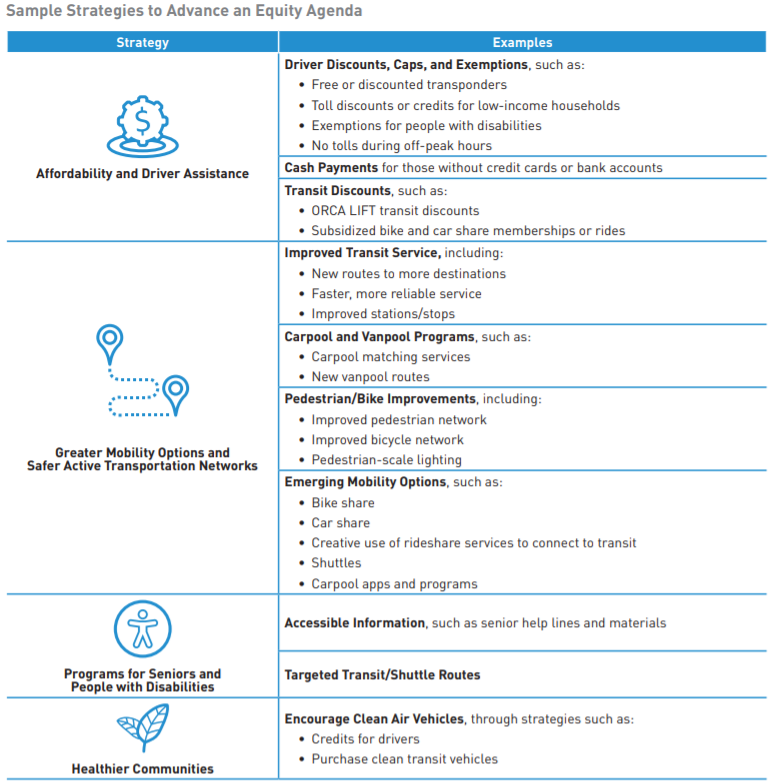

The Durkan administration cited equity concerns in its “pivot” away from downtown decongestion pricing, but those concerns and possible solutions to them have been widely covered since her administration embarked on the plan. We at The Urbanist suggested a few in our initial coverage. The congestion pricing study that Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) released in May 2019 found that most people who drive Downtown are high-wage earners and stressed the need for an equitable design to the program.

The study found that pricing works. “In every case, congestion pricing has reduced vehicle trips, reduced CO2 emissions, and lowered travel times,” study authors wrote. They also suggested a host of ideas to promote equity through the program, such as discounts for low-income motorists.

Very little happened next. The Durkan administration didn’t turn the study into an actual policy proposal, and then quietly informed the Seattle City Council they were pivoting away from the idea in fall 2020, KUOW’s John Ryan reports. The news wasn’t really a surprise since Mayor Durkan had neither mentioned decongestion pricing in her brief state of the city speech in January nor her previous 2020 agenda-setting speech nor really much at all since the initial push in 2018 and 2019.

“One policy that never got a mention in the speech was congestion pricing, which Mayor Durkan had previously presented as a first-term priority key to her climate strategy,” I wrote after her February 2020 state of the city speech. “Inevitably, congestion pricing will face a tough political fight to pass, but that fight is made tougher by the Mayor’s plan to run it as a ballot initiative before voters ever get to see it in action and reap the benefits. The City will be conducting outreach this year to craft the specifics of the proposal and build support, but it seems unlikely that it’ll be on a ballot before 2022 — unless the Mayor is ready to stake her reelection campaign on it in 2021.”

That reelection campaign never materialized after Mayor Durkan’s popularity nosedived in 2020. Durkan faced criticism as she stood by her police department as it tear-gassed and blast-balled Black Lives Matter protesters, medics, nurses, journalists, and bystanders alike, and oversaw the abandoning of the East Precinct building when the protesters persisted. The Mayor drolly declared it “a summer of love,” simultaneously alienating the Left and the Right in one masterful stroke. In December, the Mayor announced she was not running for re-election, arguing this would allow her to focus on executing on policy in her final year. Road pricing was no longer on her mayoral bucket list, though the Mayor said road pricing would still be considered as part of broader equity-minded reforms.

“Given recent community feedback and the evolving nature of the dual crises of COVID-19 and systemic racism, the staff leading this effort are pivoting the conversation from specifically addressing ‘Congestion Pricing’ to instead focusing on how best to fund the transition to a more equitable transportation system,” the Mayor’s Office wrote to council members according to KUOW. “Pricing will be considered, along with an exploration of other progressive funding tools that can support [greenhouse gas] reduction and invest in a more equitable transportation system.”

In its place, her administration released an “electrification blueprint” last week, which we would spend more time covering if it wasn’t so likely to end up in the dustbin like the pricing scheme that preceded it. The blueprint’s goal of creating an emissions-free zone is a good one, but the Durkan administration’s track record delivering even on the intermediate steps to get there is not good. Progress on new walking, biking, and transit infrastructure has slowed.

When Durkan first announced her congestion pricing push, it was the same week she delayed the rollout of several key protected bike lanes Downtown. Delaying or canceling bike lanes, RapidRide projects, and the Center City Connector streetcar has become a hallmark of her administration. Without a steady pace of walking, biking, and transit improvements, it’s hard to imagine how an emissions-free zone or a pricing system would thrive, let alone get off the ground. Ryan Packer highlighted the dearth of progress on the bike network under Durkan in their writeup in Seattle Bike Blog.

“That goal actually comes directly from a commitment the City made in 2017, when then-Mayor Tim Burgess signed onto a declaration along with eleven other cities from around the world to ensure that a major zone in their city is zero emission by 2030,” Packer wrote. “At the time, Mayor Burgess was quoted alongside Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo as saying, ‘Responding to climate change’s threat requires big thinking and bold action.’ Paris has proceeded with a fundamental reshaping of the city’s streets, with around 30 miles of pop-up bike lanes added in just 2020 that will likely all remain permanent. Seattle built around 2 miles of protected bike lanes last year.”

Visionary mayors like Hidalgo were rapidly pedestrianizing streets and deploying protected bike lanes before the pandemic and ramped up the pace after declaring Covid emergencies in order to give residents more options to safely recreate and get around their neighborhoods. Mayor Durkan did greenlight the Stay Healthy Streets program that topped out at about 25 miles worth of open streets. The method was primarily to deter through traffic on existing neighborhood greenways with temporary signs and barriers. The greenways should have been designed this way from the jump, but it was a welcome change.

There was a problem though: Stay Healthy Streets mostly snaked through single-family areas and never reached mostly avoid apartment-heavy areas and business districts. We argued for greatly expanding the program and focusing on the densest neighborhoods, where the lack of open space was most acute and physical distancing to limit Covid spread most challenging. By fall though, SDOT had begun to dismantle parts of the open streets program, such as the highly popular segment on Lake Washington Boulevard, rather than continuing to expand it. While Mayor Durkan pledged to make 20 miles of open streets permanent, she did not fund it in her subsequent budget. That put SDOT in the awkward situation of proposing to shelve some more bike projects in order to scrape together money to continue the open streets program.

All this is to say big visions are well and good, but an administration also needs to take all the smaller steps to get there — sometimes in the face of fierce resistance from some neighbors and business owners. Fewer cars polluting Seattle would be good. Emissions-free zones would be great. The path is paved in smaller, less sexy projects like repairing and adding sidewalks, protected intersections, road diets, and a complete network of protected bike lanes and frequent bus lines.

The pandemic has given us a temporary respite from the severe congestion that has plagued Seattle — if not the deadly crashes. But we can’t take it for granted or let it go to waste. Now while traffic volumes are lower would be the perfect time to add dedicated bus lanes, pedestrianize streets, and pilot protected bike lanes. If we start now, we might not find ourselves chasing the next fad in four years’ time in an effort to rebrand the last four years of spinning our wheels.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.