It was fitting for my first full day in the Pacific Northwest to start off with a cold and rainy January morning. As I left the Red Lion hotel in Downtown Bellevue to head to my job interview, I had my first chance to glimpse the city by the light of day, and I have to say I was impressed. The towering skyscrapers, busy interstate traffic, and public transit all highlighted by the wet, reflective glow of asphalt conjured recollections of my brief time in Atlanta’s Midtown, not of the suburbia I was familiar with and had been told Bellevue was emblematic of.

Equally surprising (and beautiful) was my brief trip on the Lake Hills Connector; I had certainly been familiar with Washington’s status as “the Evergreen State,” but the moss-covered stands of coniferous trees were a more Northwest aesthetic than I could have possibly expected and a calming accompaniment to my otherwise nervous drive.

The job I had traveled across the country to interview for was at customer service call center in Eastgate. Being on the phone for several hours a day was admittedly not the ideal post-college position for someone with clinical social anxiety, but I chose to power through the process for two main reasons. First, I saw it as the best opportunity available to put my degree to practical use (a B.S. in German Studies from renowned science and engineering school Georgia Tech — I know, go figure). Second, it was my path to establishing roots in a region I had always longed to be a part of. Even before setting foot in Cascadia, its cultural reputation as a forested, chill, liberal, unique, and beautiful place cemented my desire to move there — to belong there.

In my research from the opposite coast, Bellevue had stood out as the natural place for me to settle. Wary of long commutes and moving to a big city that was too different from the familiar suburbia of my youth, I was very impressed by the juxtaposition I had seen that morning. An affluent city with access to real urban amenities while being surrounded by parks, natural areas, and neighborhoods was different from any place I had called home before, and I was enthralled by the prospect of living here. As the HR representative gave me a tour of the fourth-floor offices, complete with their floor-to-ceiling windows and vistas of grey, misty forests in front of the Bellevue skyline, my fate was sealed: this was where I wanted to be.

My endurance for that job may have only lasted three months, but the love for my new hometown has persisted ever since my arrival in early 2015. I’ve since learned that Bellevue’s very proud of its moniker as “a City in a Park,” and my love of this town is definitely directed to both parts of that phrase. I love going to the Garden D’Lights in the Bellevue Botanical Gardens every year and was very disappointed when they were (understandably) canceled in 2020. I love gathering with fellow Sounders fans in bars Downtown and celebrating playoff victories with drunken bus rides home. I love experiencing and learning from our city’s diversity at Crossroads Mall — at first glance a typical suburban mall, yes, but that facade belies its deeper function as a third place, belonging to and reflecting the soul of the community. Contrary to the stereotypes held by many of our compatriots west of Lake Washington, there are myriad reasons to enjoy and be proud of Bellevue as a home.

However, I’ve witnessed this pride be weaponized countless times by people and organizations who benefit from the status quo. Jon Talton’s description of Bellevue as a city benefiting from Seattle’s overly progressive “foibles” is certainly not a novel perspective. The narrative of Bellevue’s perceived superiority has existed amongst our city’s residents long before KOMO’s “Seattle Is Dying” defined the genre — though the piece’s staying power in City Council testimony, in spite of its numerous sensationalized claims, is grimly impressive.

Talton’s economic observations, in lieu of adding new arguments to the discussion, touch on territory well-trodden by prominent conservative leaders: Bellevue’s “leadership wants to work with businesses rather than penalize them,” he notes without acknowledging the city’s woeful unpreparedness for the environmental and social toll that rapid influxes of workers will create. His social observations uncritically look at the civil unrest and protests around racial justice without examining context and undeniable acts of police brutality that predicated protestors’ actions.

Honestly, the piece weaves together several shallow but frequently-parroted threads in a comprehensive way that would be impressive were it not so damaging. However, giving further argumentative fodder to the “Bellevue rules, Seattle drools” crowd so they can confirm their preconceived biases has real material harm. It provides yet another poorly-founded cover for neighbors who are content with the status quo to hide behind in Council testimony, Nextdoor forums, and community group discussions while they block meaningful progress towards making us a city that welcomes the world. Intentionally or not, publicized perspectives like these allow our city’s residents and leaders to shy away from examining our own very real shortcomings.

Police

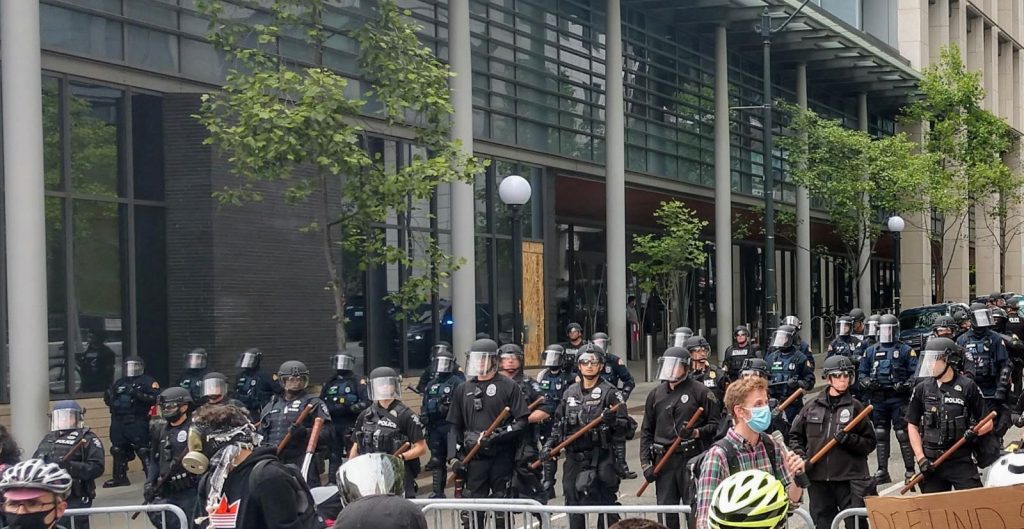

For example, our region’s collective focus on the atrocities committed by the Seattle Police Department (SPD) allowed Bellevue’s Police to escape the summer civil unrest with its reputation largely intact, despite two officers being put on administrative leave in the span of two months.

Officer Nico Roche, who retweeted numerous Q-Anon conspiracy posts over the course of several months in 2020, was ultimately let off with a written reprimand and was left on the force. In spite of uncovering in an interview that Officer Roche knew what Q-Anon followers believed, that he regularly sought out podcasts and media espousing conspiracy theories, and claimed that he was drawn to Q-Anon by “positive messages of equality and unity” (in spite of his tweets representing anything but unity), the independent investigating firm found that “Officer Roche [does not ascribe] to…improper ideologies that call into question his fitness to serve as a law enforcement officer.”

The second officer, David Wright, was put on administrative leave for one and a half months before ultimately resigning from the department because of a domestic violence assault in Redmond.

These incidents, when combined with a recent $125,000 police brutality settlement and the massive and intimidating overreaction to peaceful protestors in October, reveal a public safety apparatus deeply in need of reevaluating — not much unlike our neighbors to the west.

Racial Equity

Underneath nearly all issues of police brutality and accountability are important discussions around racial equity. Beyond questions of “What do police protect: people or property?” and “Which groups are safest and whose interests are protected if the status quo is maintained?” are some deeper debates about our city. “Who is Bellevue for?” and “Who can belong?” are questions that, for a significant amount of time, had explicitly racist answers.

As recently as 70 years ago, Bellevue neighborhoods had land covenants which excluded nonwhite people from owning or renting property. The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II had a particularly inhumane toll on the 300 Bellevue residents who were forced to vacate their homes. After internment, most families did not return. Those that did were greeted with hostile neighbors and ransacked properties.

Although these horrible policies were enacted and vanished long before most of us were born, their impacts persist to this day. Miller Freeman, ancestor of current Bellevue Square owner Kemper Freeman, Jr., was one of the most outspoken voices fomenting anti-Japanese sentiment in the early 20th century. His actions had direct policy consequences which made it impossible for Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans to own property. Because of the impacts of inter-generational wealth, his descendants’ prosperity and influence in Bellevue politics are in large part owed to this explicitly racist legacy. All of this does not even touch on the legacy of exclusionary single-family zoning, which creates artificial scarcity that has historically made it disproportionately difficult for Black and Brown people to afford homes.

It is most certainly possible for residents and elected leaders to not know about these issues. At first glance, it can be hard to draw direct connections between policy choices from decades ago and real-world outcomes today. However, when less than 3% of current Bellevue residents are Black, significantly lower than our neighboring jurisdictions, it is imperative that we start asking some important questions: “How did we get here?” and “Where do we go from here?” It is sometimes hard, but the answers to those questions must acknowledge the historical harms and involve changes to policies that have and continue to do harm. The discussions around racial equity and atoning for previous sins are just as relevant for Bellevue as they are for Seattle. Let’s not pretend that we can sit this one out.

Affordable Housing and Homelessness

Talton’s take on affordable housing funding is perhaps the most lacking in nuance and completely ignores Bellevue’s history in contributing to the housing crisis our region faces today. Putting aside the problems with our city’s land use policies (which The Urbanist‘s Doug Trumm explored heavily), Talton’s uncritical citing of the 25,000 additional Amazon workers coming to Bellevue by 2025 as a positive for the city has a fundamental flaw. Not only does he fail to examine how this rapid influx of workers will impact our limited affordable housing infrastructure, he doesn’t draw attention to the affordability crisis that Bellevue is already facing!

Even before Amazon’s announced arrival, the City Council’s 2017 Affordable Housing Strategy target of 2,500 affordable units created or preserved in 10 years is but a drop in the bucket for the 16,000 Bellevue households, or 30% of residents, who are already cost-burdened by housing. Nearly 11,000 households are presently below 50% Area Median Income (AMI), and although Bellevue is currently slightly outpacing the forecast set by the Affordable Housing Strategy, only 11% of the 1,223 affordable units added since 2017 have been for people making less than 30% AMI, the residents most vulnerable to homelessness.

Additionally, Bellevue reneged on its responsibility to contribute to a regional solution when Council voted to supersede County action that would’ve targeted housing initiatives towards this vulnerable group, instead choosing to collect its own tax to be spent on city initiatives focusing on higher AMI units. This lack of urgency to meet the very real need for affordable housing places the city in a precarious position; either these new workers will live in the city, likely displacing current residents and driving housing costs even higher due to policy failures, or Bellevue will rely on workers commuting from other cities, who will subsidize our affordable housing needs. None of this has even touched on how we have nine years to enact significant policy changes to prevent the worst impacts of climate change, how land use reform must be an important part of that transformation, and how Bellevue’s emission reduction progress has been lagging (although there is some room for optimism).

Forgotten in Talton’s perspective is the responsibility that municipal governments have to their citizenry beyond merely fostering a good economy. Governments are (and should be) tasked with missions of equity, sustainability, justice, and affordability, because these are policy goals that the private sector cannot achieve alone. Reducing the narrative of our region to one highlighting Bellevue’s economic success at the expense of Seattle’s because of the latter’s overly-“woke” electorate is unfair to those of us trying to find comprehensive solutions to meet the moment posed by Bellevue’s (and our region’s) many crises. To allow the story Talton puts forward to uncritically remain the prevailing narrative of our region is a disservice both to the residents who demand accountability from our city’s leaders and to the organizations and neighbors who want Bellevue to be a more equitable, sustainable, and safe place to call home.

Final Takeaways

After an entire article pointing out my city’s policy faults, it’s certainly important to acknowledge several key points. First, I am not advocating for a Seattle-sized solution to all of Bellevue’s issues. As Talton rightly notes in his piece, Bellevue is not (and will not be) Seattle. Due to our size and our position in the larger county-wide ecosystem, we will less be able to enact meaningful changes on our own. We must rely on regional partnerships and collaborations with neighboring jurisdictions, including Seattle, that distribute costs and responsibilities fairly and equitably. This task is not well-served by publishing a perspective that (intentionally or not) entrenches preexisting narratives that sow division with our largest neighbor.

Second, there are many local leaders who understand the urgency of these crises and are leading the charge in addressing them. In this year’s budget, Bellevue City Councilmembers Jeremy Barksdale and Janice Zahn introduced funding for their Bellevue Centers Communities of Color initiative, which seeks to build authentic relationships and community-directed plans to update Bellevue’s equity policies. These Councilmembers have undertaken critical work to help make equity a core tenet of all municipal operations. King County Council Chair Claudia Balducci is another star advocate for our city — one who frequently speaks about (and acts to address) the intersections between transportation, land use, affordability, and climate change. And our city is well-served by the many organizations fighting for a just and sustainable future that works for all of us.

Finally, in spite of all these faults, I still love my city. Nothing that I cited above can take away the life I’ve built here, the communities I’ve been a part of, and the experiences I’ve shared with them. Some readers may take all the arguments above as evidence that I’d be happier in Seattle — and they’re not necessarily wrong. People of my persuasion might certainly be more common in Seattle, but I’ve taken great joy in finding and building the communities of people to whom solving these intersecting crises equitably and sustainably is a priority — and contrary to Talton’s implication, I believe these people are more common here than he thinks.

I didn’t experience a sunny day in that Eastgate office until a week after I had started the job. The lighting gave the forest a different hue than what I had gotten used to, but that wasn’t the only interesting development. For the first time, I could see the Seattle city skyline in the distance: the Columbia Center standing tall, the Space Needle barely poking above the hilly horizon. I had hardly even explored the region at that point, choosing instead to get settled in my new apartment and finding ways to spend time nearby. I have a lot of memories from back then of sitting in Bellevue’s Downtown Library and getting some internet time in before getting out and walking around Downtown. As weird as it may sound, those early experiences were rather formative for me in developing a sense of place and a connection to my new home. Those days were long before I truly understood the gravity of the crises we find ourselves in, but these experiences unintentionally defined my present identity in ways I wouldn’t have understood at the time. No matter the allure of the Seattle skyline in the distance, Bellevue is my home, and my home deserves a community that will work hard to make it better for everyone.

Chris Randels is the founder and director of Complete Streets Bellevue, an advocacy organization looking to make it easier for people to get around Bellevue without a car. Chris lived in the Lake Hills neighborhood for nearly a decade and cares about reducing emissions and improving safety in the Eastside's largest city.