How King County Metro will restore bus service as the pandemic recedes will be a hotly contested issue. Metro offered a window into the process this week with a presentation on how the agency has been responding to ridership demand changes during the pandemic civil emergency and how an exit from the pandemic could work. There were strong hints that permanent changes could be made as a result of trends where demand has changed. That could mean service cuts in areas where pre-pandemic demand was high. Metro also spoke to some very unpopular bus restructure approaches surrounding light rail expansion and deployment.

Where Metro stands and is headed

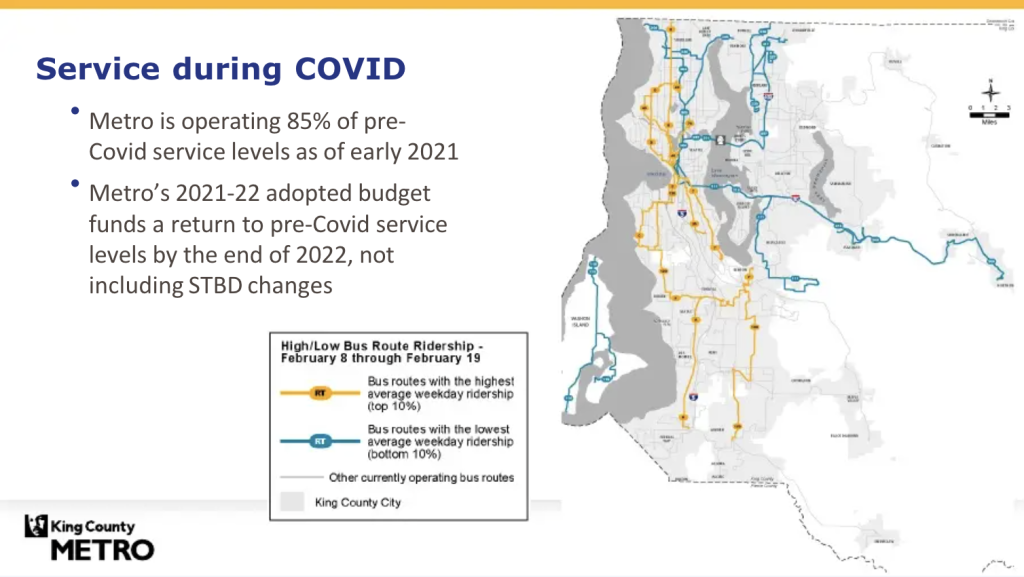

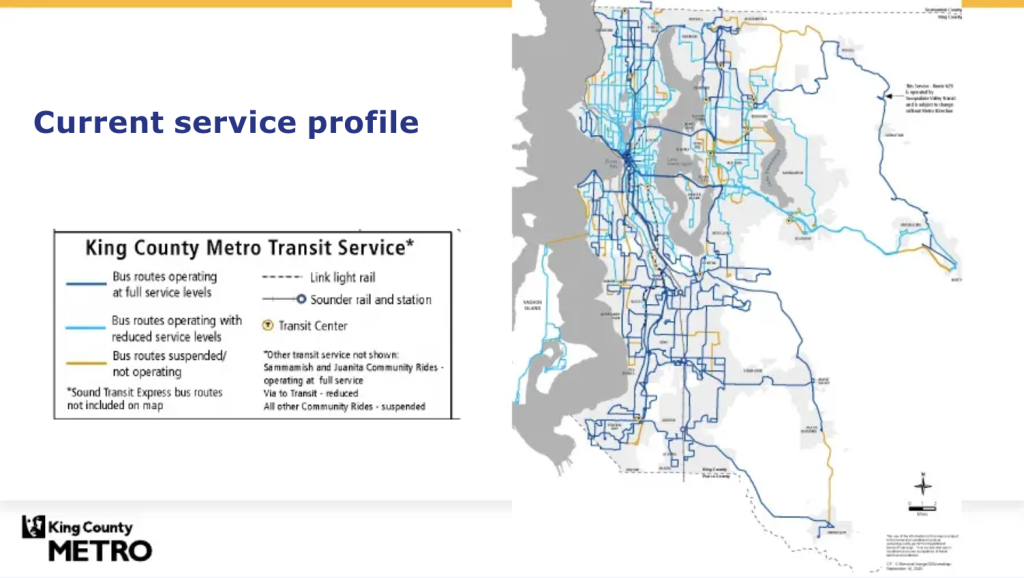

Right now Metro is operating at 85% of pre-pandemic service levels with daily ridership averaging 125,000 (about 30% of 2019’s average). Routes with the smallest ridership declines are all-day routes, RapidRide routes, and routes in South King County. The agency has temporarily suspended 414,000 annual service hours.

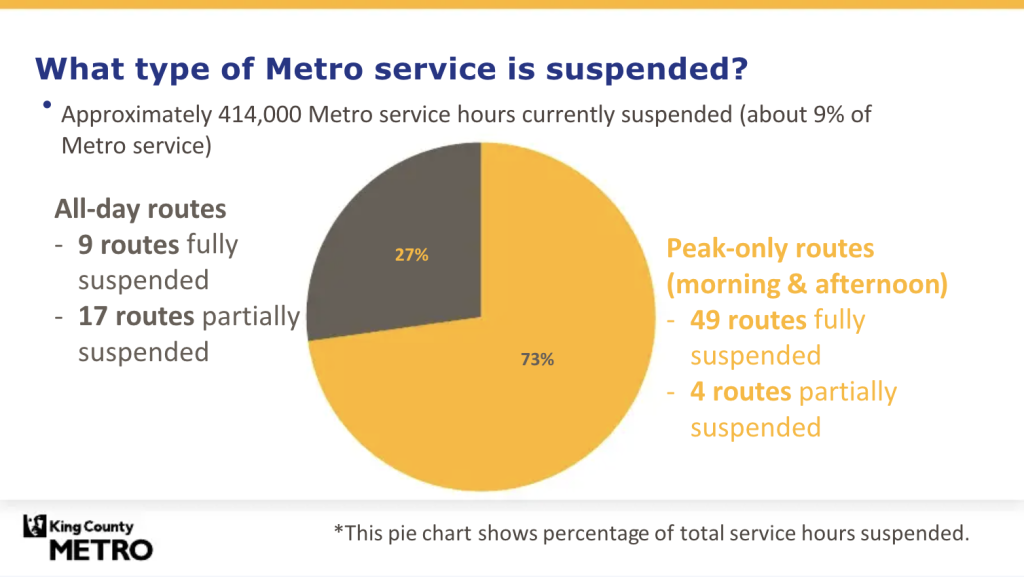

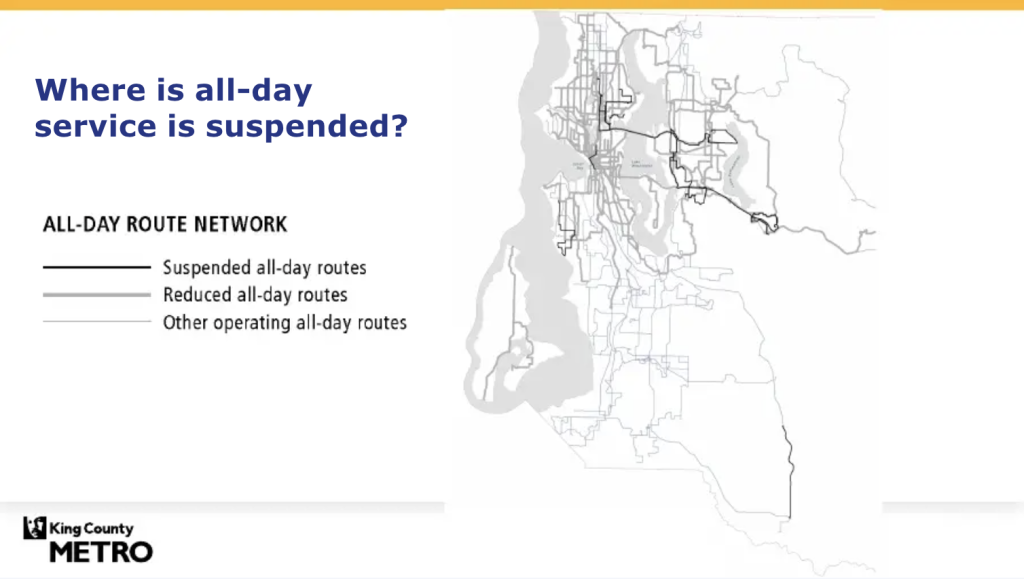

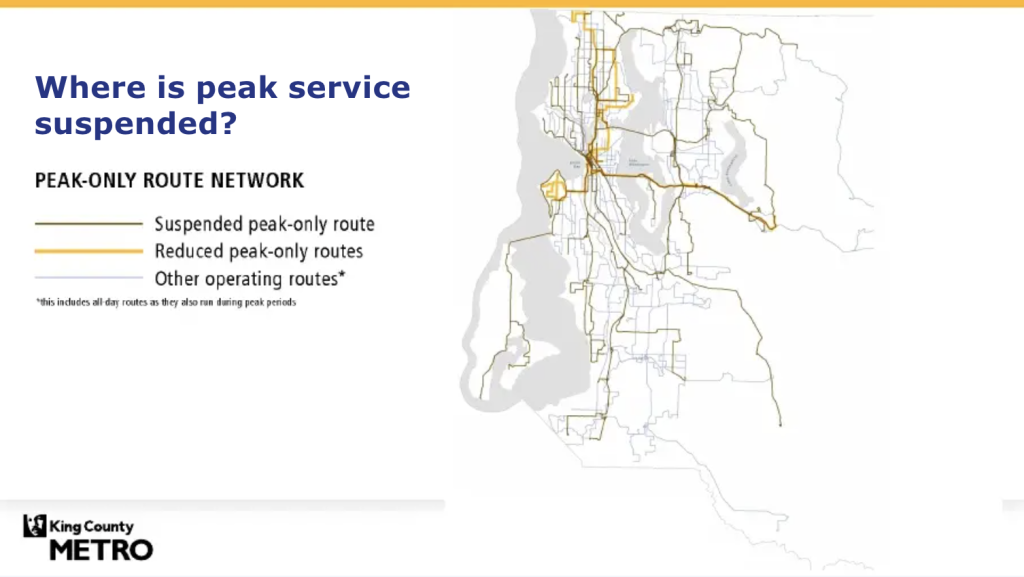

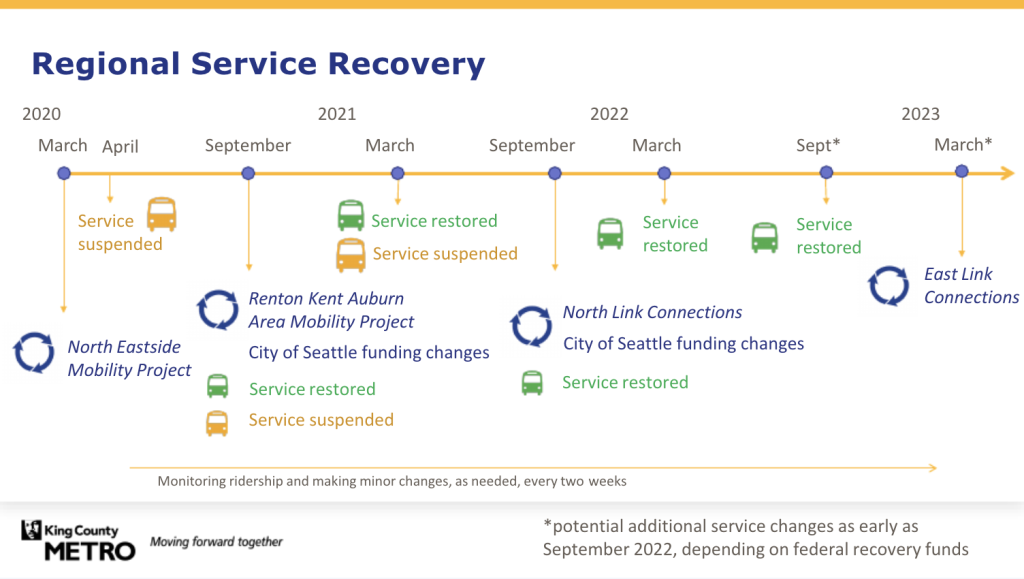

The vast majority (73%) of the suspended service hours fall into the peak-only route category, which has meant fully suspending 49 routes and partially suspending another four routes. All-day routes — the smaller category of suspended service hours (27%) — are affected, too, with nine fully suspended and 17 partially suspended routes. Most of the all-day routes affected by suspensions are in Seattle and the Eastside whereas peak-only route suspensions are all across the county. Metro is poised to restore a very small number of service hours this month with the bulk of restorations coming in the fall when the agency brings back another 200,000 annual service hours.

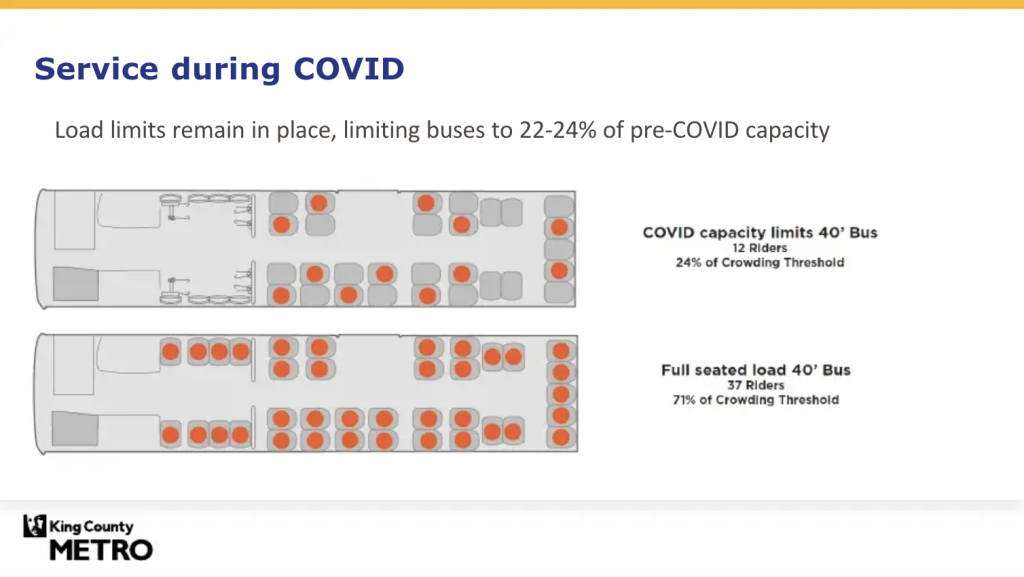

Capacity of buses remains at 22% to 24% to provide for social distancing of passengers. For the purposes of service planning, 24% capacity is being treated as a “crowding” threshold in allocating additional trips to routes to reduce passenger loads. Ordinarily the crowding threshold would be at 71% of bus capacity inclusive. Capacity is inclusive of standing and seated passenger limits.

Metro is trying to be strategic in how service restorations will be made once the pandemic civil emergency ends. The agency plans to use several factors in that decision-making, including ridership, crowing, equity, productivity, and employers.

For ridership, Metro will look to last year’s system evaluation report that is based on the Service Guidelines. Routes that had higher ridership pre-pandemic will be prioritized using that report. Crowding will continue to be based off the current lower threshold for social distancing purposes, making midday and afternoon periods the highest immediate priority. This is especially the case for the RapidRide A and E Lines and Routes 7 and 36. But this will eventually revert back to the normal crowding threshold metric once social distancing protocols lapse.

On equity, Metro will look toward filling service gaps in Equity Priority Areas that are served by routes with high Opportunity Scores. Equity Priority Areas have higher rates of priority populations, such as people of color, people who are low-income, or people who were born abroad. And then there is the metric of productivity where Metro intends to continue de-prioritizing service restoration on routes that had low productivity under the Service Guidelines pre-pandemic. These routes tend to be peak-only routes, though there are all-day routes that rank in the bottom 25% of all routes with similar operational periods and service characteristics. Routes that into the bottom 25% for productivity would ordinarily be candidates for permanent service reduction and there is a high probability that suspended service on them could be permanently reduced.

The agency has also begun looking at a variety of key data and engaging major employers and stakeholders, and conducted a wildly expansive online rider survey — which was so long as to be useless. Metro hopes to complete a model to estimate work-based ridership demand for the fall.

The model is based on a combination of ORCA transit pass data, rider surveys, and direct discussions with employers like the major hospitals, REI, Amazon, Expedia, and University of Washington. These employers are particularly key because many of them have ORCA Business accounts for employees. Workers who hold those employer-provided ORCA passes accounted for 41% of all boardings and 51% of fare revenue for Metro in 2019, but ridership among those passholders has fallen 85%.

Employers have so far indicated that they expect to see workers and students begin reporting to their worksites and campuses in the summer, but more earnestly in the fall. This, of course, is predicated on the trajectory of the vaccine rollout and how effective vaccines will be at suppressing the pandemic longer-term.

Employers have also generally indicated that they intend to permanently adopt a hybrid workplace approach where workers will be able to split up the workweek at home and the office. This presumably could cut daily office worker loads by half, which would be a huge demand change to downtown office centers. Still, workers may make more local trips throughout the day, so such a shift does not necessarily weekday ridership amongst this group would fall by half permanently. It does, however, suggest that peak-only routes and service may become less important in the network.

Metro’s road to recovery may stretch out through 2023. The bulk of service should be restore in the fall and next year. Federal funding assistance from the American Rescue Plan Act will no doubt be a boon, plugging the revenue hole from reduced ridership and farebox recovery.

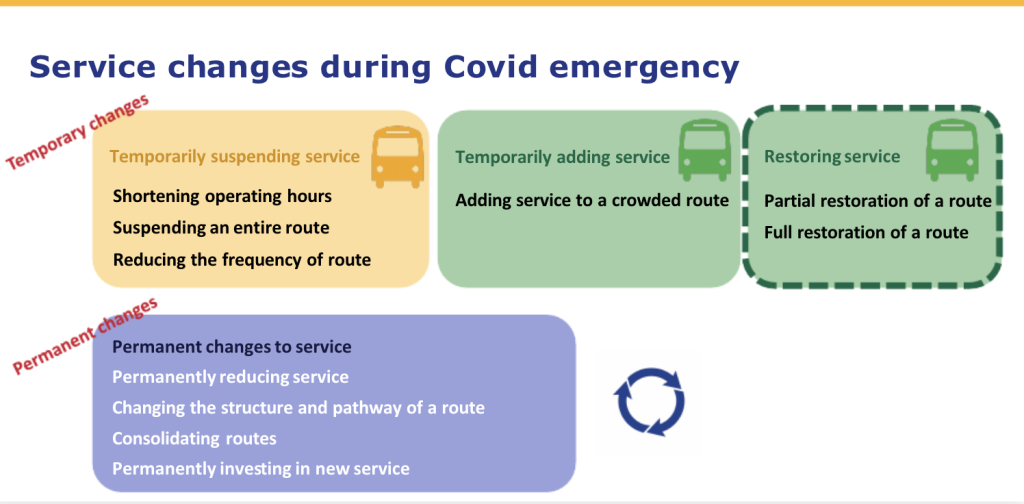

Going forward, Metro will have a more solid strategy and set of policies to deal with a range of civil emergencies that make require alterations of service. A likely scenario is the mega-earthquake that the region may be due for that could gravely hamper service. Updates to the Service Guidelines will include situational responses to a variety of scenarios and provide flexibility in how changes will be made. This could include temporary service suspensions and additions and partial service restorations. A civil emergency may also greatly affect long-term performance of routes necessitating permanent changes.

In terms of the pandemic, Metro has promised that the agency will use pre-pandemic data for service restorations once the civil emergency has ended. But that does not mean further service changes according to the Service Guidelines are permanently forestalled. If ridership remains low, that could mean eventual cuts to some routes and service reinvestments elsewhere. However, Metro cannot make a permanent reduction of routes more than 25% under the Service Guidelines without approval from the Metropolitan King County Council.

Future bus restructures around light rail are thorny

In terms of the bus restructure issue surrounding light rail expansion, updates in Metro’s Service Guidelines will provide more clarity on how this should occur. Route 41 is an example of where Metro is deleting a duplicative route from Northgate to Downtown Seattle once the Northgate Link extensions opens in the fall. Its 47,000 annual service hours are to be reinvested South King County, not the North Seattle/Shoreline area in accordance with the agency’s equity framework. This could continue to be a thorny issue since service hours that Metro had been providing to a community may simply evaporate when new light rail service is delivered.

Metro, however, contends that the service light rail provides is superior to equivalent bus service and that the practice of deleting routes around bus-light rail restructures would only apply to truly duplicative routes, not other local routes. That means all other local bus service hours that are modified by bus-light rail restructure would stay within the service area.

Policymakers and local officials still worry that they could wind up losing critical service hours that they pay for and that dwindling service hours in a service area near light rail stations could hamper the efficacy of light rail service itself. Put another way, if the 47,000 annual service hours saved from not running Route 41 were reallocated in the North Seattle service area, Metro could ramp up local routes to be even more frequent and possibly add more east-west service to connect communities and the light rail stations.

However, the double whammy of the pandemic zapping revenue and Metro scurrying away Route 41 annual service hours from North Seattle/Shoreline wound up making the Northgate Link bus restructure feel more like an exercise in severe austerity than anything resembling an effort to improve access to light rail and communities. The “final” proposed plan was a far cry from the bold vision shared pre-pandemic — and it may not be so final after all since restructure did not factor in funds from the Proposition 1 bus measure that Seattle voters passed resoundingly. Still, it is no wonder that policymakers would fear for equally disastrous bus restructures in their communities as future light rail expansions come on line. Fortunately for the Eastside though, Metro has little duplicative bus service along the East Link and Redmond Link light rail expansions, leaving decisions on duplicative bus service mostly up to Sound Transit in 2023 and 2024.

Still, some policymakers on the Regional Transit Committee think that Metro should adopt a policy of holding back on moving service hours out of a service area for at least one to two years. That way the agency can review ridership data to see if there are actually redundancies in service needs.

The bus restructure issue will likely continue a key concern as the Service Guidelines update carries forward. The Regional Transit Committee will tackle the update at large next month, so expect more debate.

Correction: Details on capacity and productivity metrics were further clarified.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.