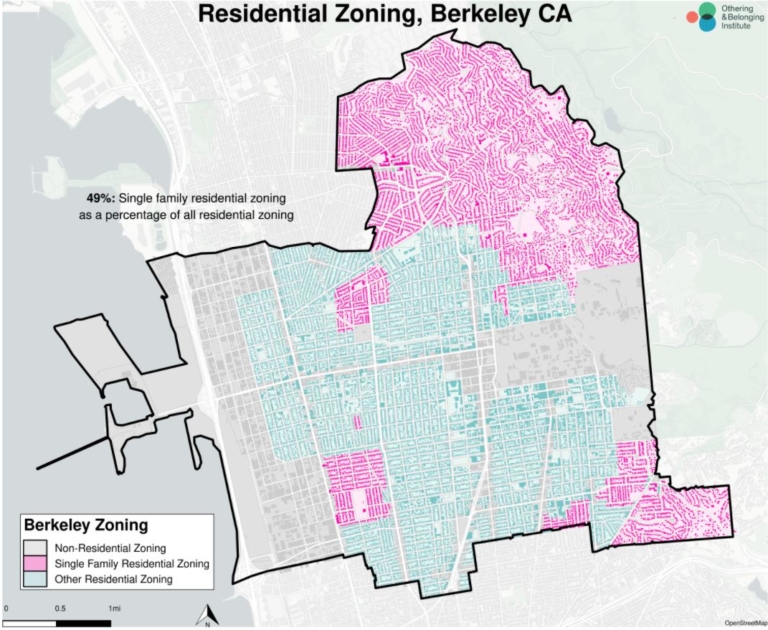

Historically, Berkeley has been a hotbed of resistance to new housing and an innovator in excluding people of color. In fact, Berkeley was the first city to implement single-family zoning in 1916. Last month, the Bay Area city took a major step in changing that legacy. The Berkeley City Council made a commitment to undo racist exclusionary zoning and put itself on a course to end single-family zoning that has frozen much of the city in amber for decades.

The city council’s Resolution to End Exclusionary Zoning is symbolic at this point, but it sets the end of 2022 as a deadline to arrive at a plan to begin dismantling exclusionary zoning and reintroduce multiplexes in all neighborhoods. Crafting the plan will involve considerable outreach and debate. Ultimately, Berkeley could follow in the footsteps of cities like Minneapolis, Portland, and Sacramento, that have scrapped single-family zoning and moved to legalize fourplexes citywide.

Building upon Missing Middle

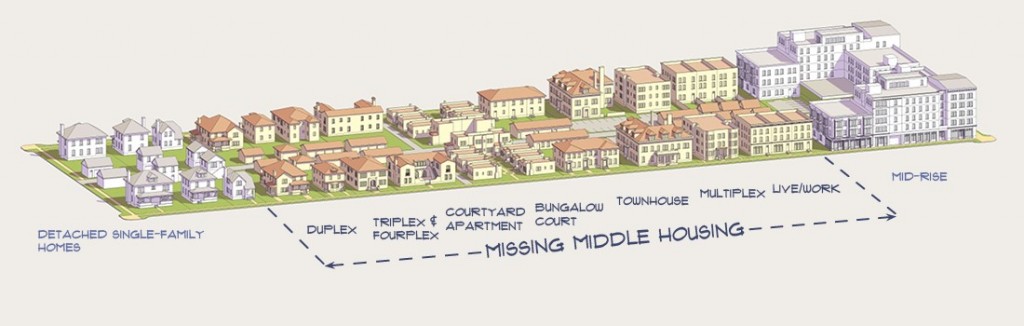

However, local housing advocates want to go further and some have a bolder vision. Berkeley-based housing advocate and architect Alfred Twu published an article and tweet thread highlighting the need for “Missing Large Housing” as opposed to just “Missing Middle Housing” that has largely dominated the discussion in planning and New Urbanism circles. Daniel Parolek of Opticos Design introduced the formalized concept of Missing Middle Housing back in 2010 and defined it as homes more compact than a detached single-family home but consisting of buildings no larger than a 20-unit apartment building. The idea caught fire among urbanists and planners–we at The Urbanist have covered or referenced it many times.

I caught up with Twu on the phone to hear more about his work, the Missing Large Housing framework, and how Berkeley housing advocates have been able to turn back the tides of housing opposition and exclusion. He acknowledged that Missing Middle Housing is a valuable and appropriate concept in many contexts.

“For your average suburban neighborhood, Missing Middle Housing is probably the best thing,” Twu said. “For somewhere that’s next to a train station or next to a giant office building, then no. Missing Middle Housing doesn’t belong there. You want something much larger. And then for rural areas, there are more rural options. We have another article coming up about Missing Small Housing, like tiny houses.” [Update: Missing Small Housing article here.]

Benefits of Missing Large Housing

Twu’s article argues that high cost metropolitan areas like the Bay Area (which would apply to Seattle and Los Angeles, too) are too in demand and too far behind in producing housing to solve their problems with fourplexes alone. Bigger solutions need to be on the table, too.

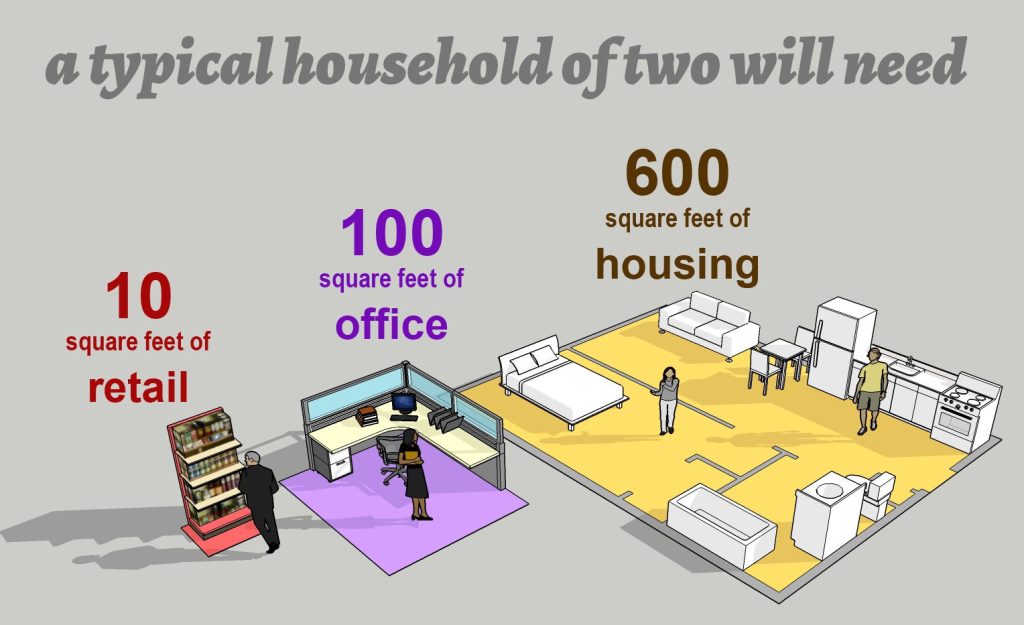

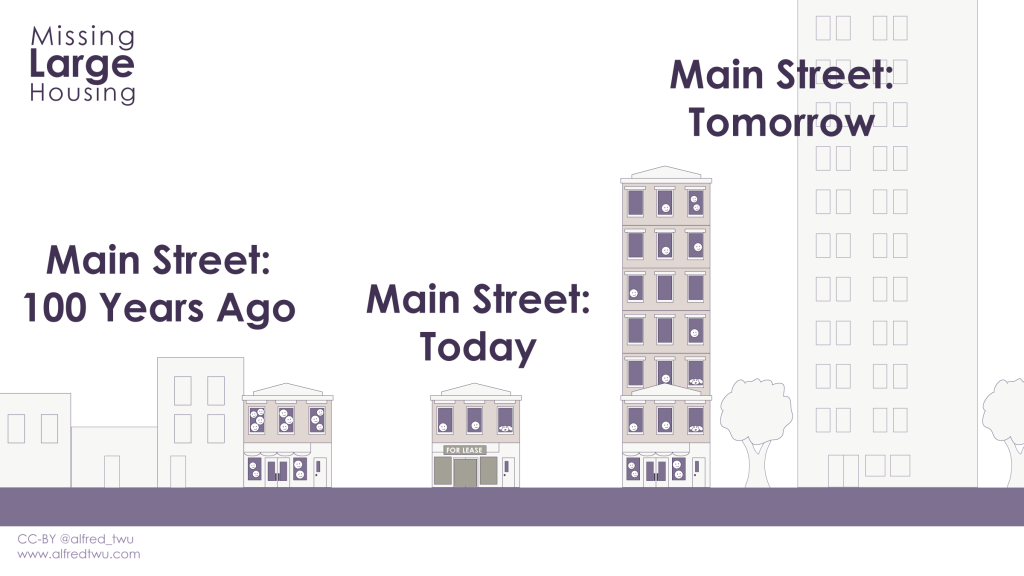

Denser housing also allows more vibrant main streets and commercial housing, Twu pointed out and illustrated in a series of graphics. A household of two will require about 10 square feet of retail space and 100 square feet of office space, to use a general planning principle. If there aren’t enough households near a commercial district, businesses will struggle to make it and vacancies will abound. If a city is dominated by single-family zoning, its commercial districts will be smaller, more fragile, and at risk of collapse. Commercial districts are also more likely to require tons of parking since residents won’t live near enough to walk, which comes with its own environmental repercussions and financial burdens for both governments and businesses.

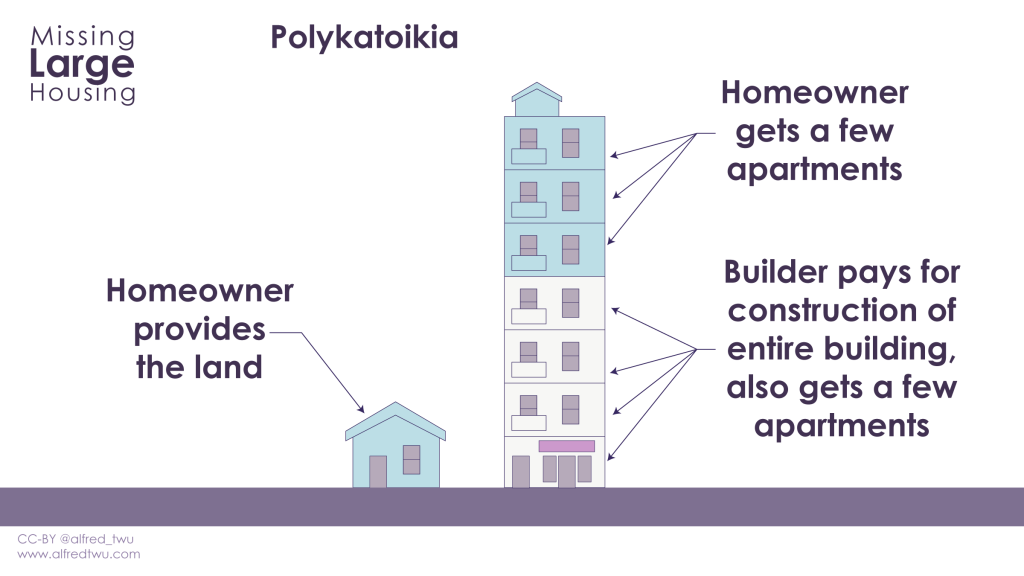

Twu points to some interesting models of development from abroad for inspiration in his Missing Large Housing framework. Among them are Vietnam’s highrise rowhouses and Polykatoikia, each of which address the problem of small lots, which can also be a hard to grapple with legacy of development single-family zoning.

“When most land in a city is already divided into small lots with individual houses, even if zoning is changed, larger buildings come slowly since most homeowners don’t have the money or skills to be a builder. In Greece, this led to Polykatoikias being built using the antiparochi, or ‘Supply in Exchange’ system,” Twu wrote. “The homeowner supplies the land, and in exchange gets a few apartments in the new building.”

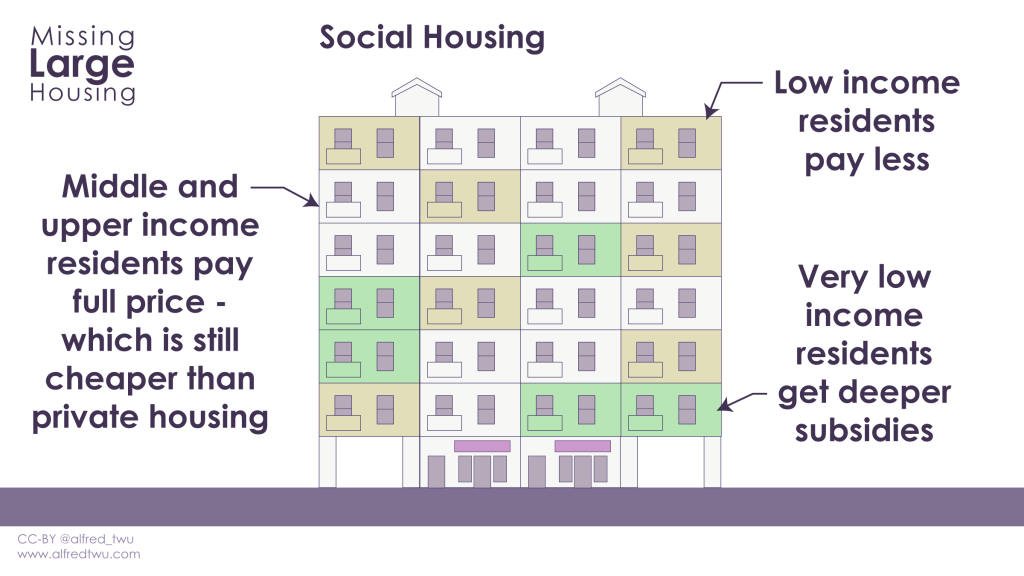

Missing Large Housing is also more compatible with social housing, which is called out in Twu’s graphic. Social housing covers public, nonprofit, public-private partnership models of providing below-market affordable housing and across the county (particularly the West Coast) it’s in woefully short supply. Given the massive need and way social housing funding and financing works, large projects do most of the heavy lifting. Unfortunately, we don’t allow typical models of social housing on the majority of urbanized land. Missing Large Housing makes space for social housing development to scale up.

Overcoming and reversing years of housing opposition

Raised in New Jersey, Twu has been living in Berkeley for 18 years, moving for college and sticking around for his career designing building small, large, and in-between. Housing development had only recently began loosening up when Twu arrived.

“It’s been a long time coming. In Berkeley in the 70’s there was a backlash against development that led to pretty much a freeze on any new development in the city,” Twu said. “So we have lots of buildings built in the 50’s and 60’s and almost nothing until the late 90’s.”

At that point, Twu said, Berkeley, spurred by anti-sprawl environmental advocacy, passed a downtown plan to put more apartments in its core. Downtown Berkeley did get built up and revitalized, but housing prices continued to skyrocket as the tech industry took off in the Bay Area. Single-family zoning neighborhoods were largely untouched.

Bringing together housing coalitions can vary considerably based on local political terrain, Twu said. San Francisco has some of the strongest tenant protections in the country and the Democratic Party is so dominant that it contains both pro- and anti-development forces. Other cities in the Bay Area are different, with Silicon Valley suburbs seeing anti-housing advocacy more associated with Republican leaders, Twu said.

Whatever the local coalition, simply showing up at public hearings to advocate for housing proposals can help counter housing opposition and get the momentum rolling, Twu said. In other words, the “Yes In My Backyard” (YIMBY) crowd can overcome “Not In My Backyard” (NIMBY) crowd by putting in the work and leading with a positive vision of the future. Adding Missing Middle Housing in suburban areas and Missing Large Housing in transit-rich areas provides a compelling alternative to increasingly expensive and segregated present. Widespread social housing, cohousing, Baugruppen, and dense shophouse models like Polykatotikia would make a brighter future.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.