Sound Transit boardmembers got a preview of Sound Transit 3 (ST3) realignment scenarios on Thursday. Agency staff walked through four examples of capital program realignment scenarios during the presentation. Each of these are based upon criteria adopted by the board last summer using funding gap assumptions. The agency is facing an $11.5 billion shortfall due to a combination of economic impacts from the pandemic and increasing project costs.

The agency envisioned that Tier 4 projects received the longest delays, which could stretch to 14 years in the no new revenue or as little as two years in the high revenue scenario. On a ridership basis, Sound Transit staff has ranked Graham Street, NE 130th Street, and Boeing Access Road infill Link stations as Tier 4, as are improvements to the RapidRide C and D Lines. However, Graham Street was ranked “high” on the equity criterion since it is one of the most racially diverse station areas in the system. Still, it is not clear if equity will be the determining factor for Sound Transit boardmembers or something else like ridership, phasing, or completing the spine among the eight criteria for realignment.

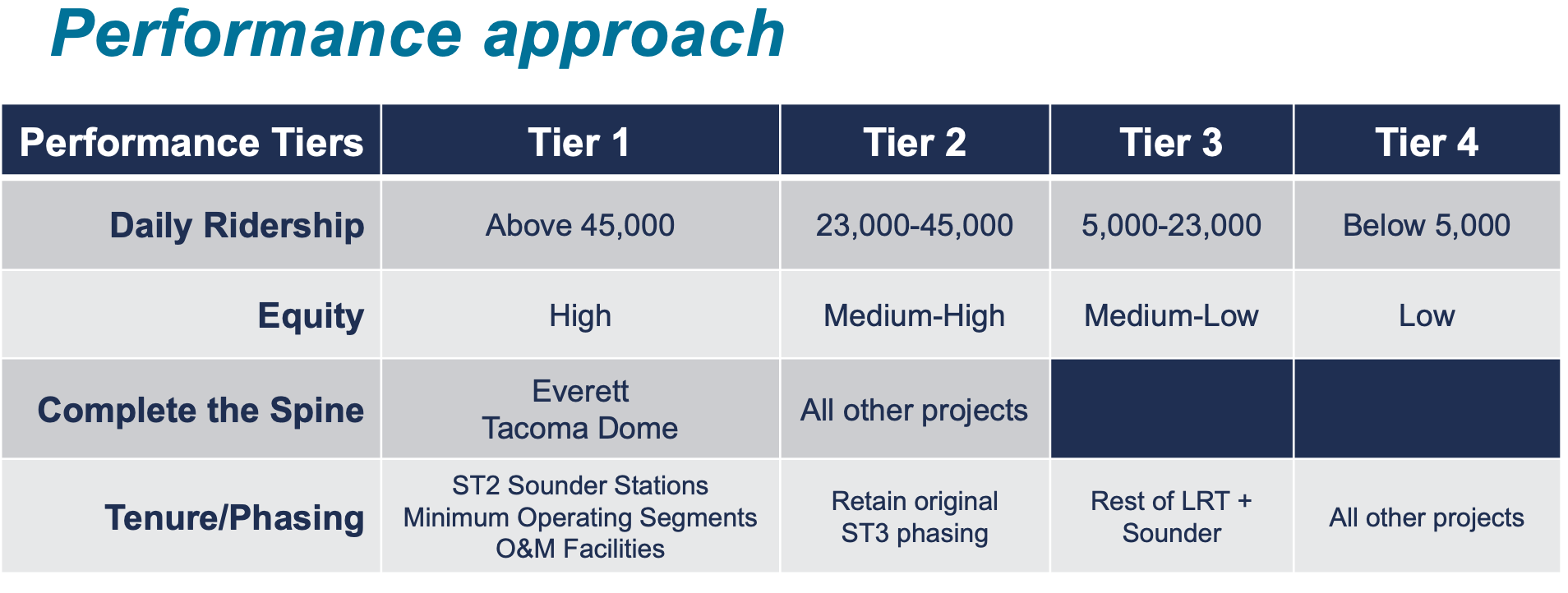

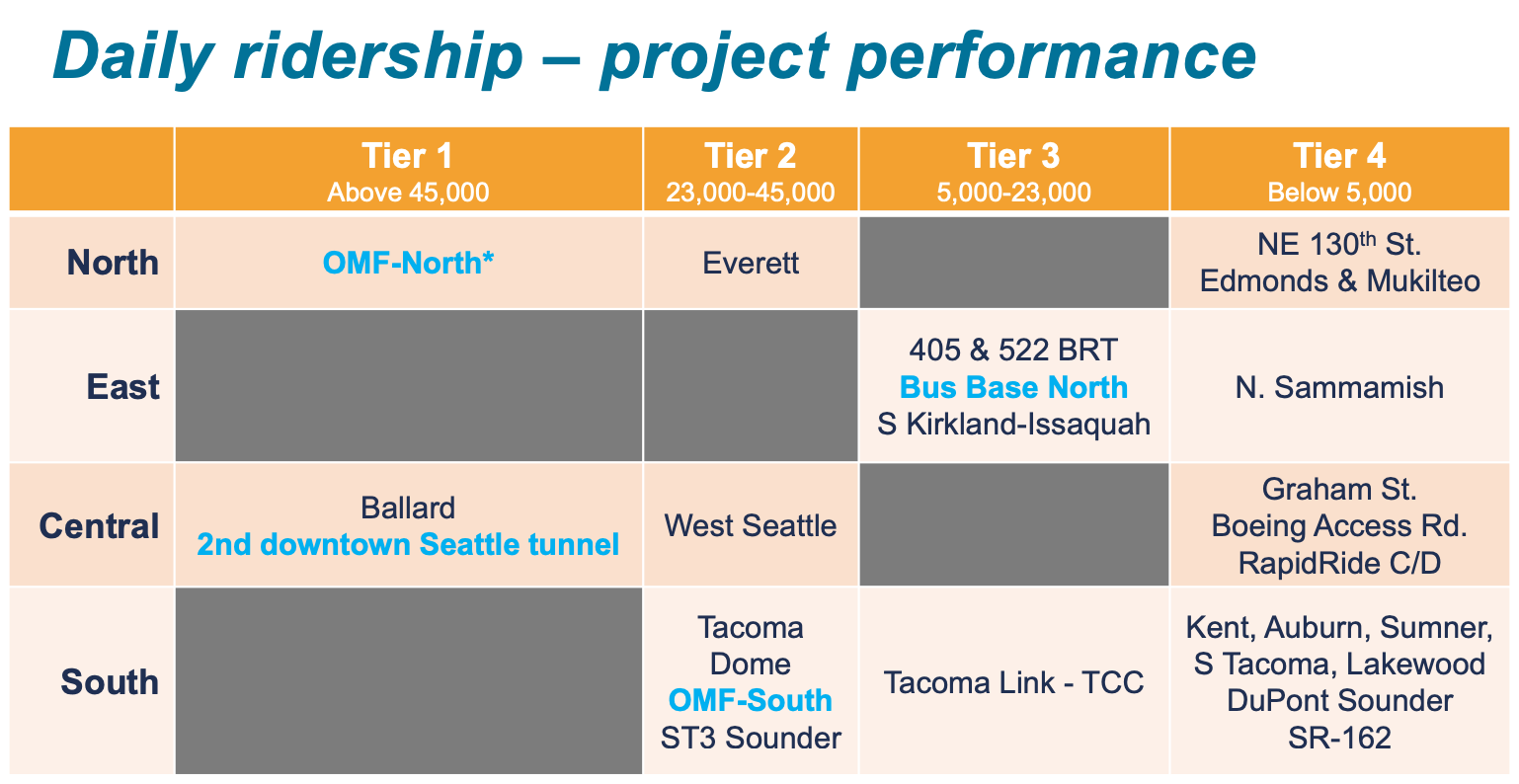

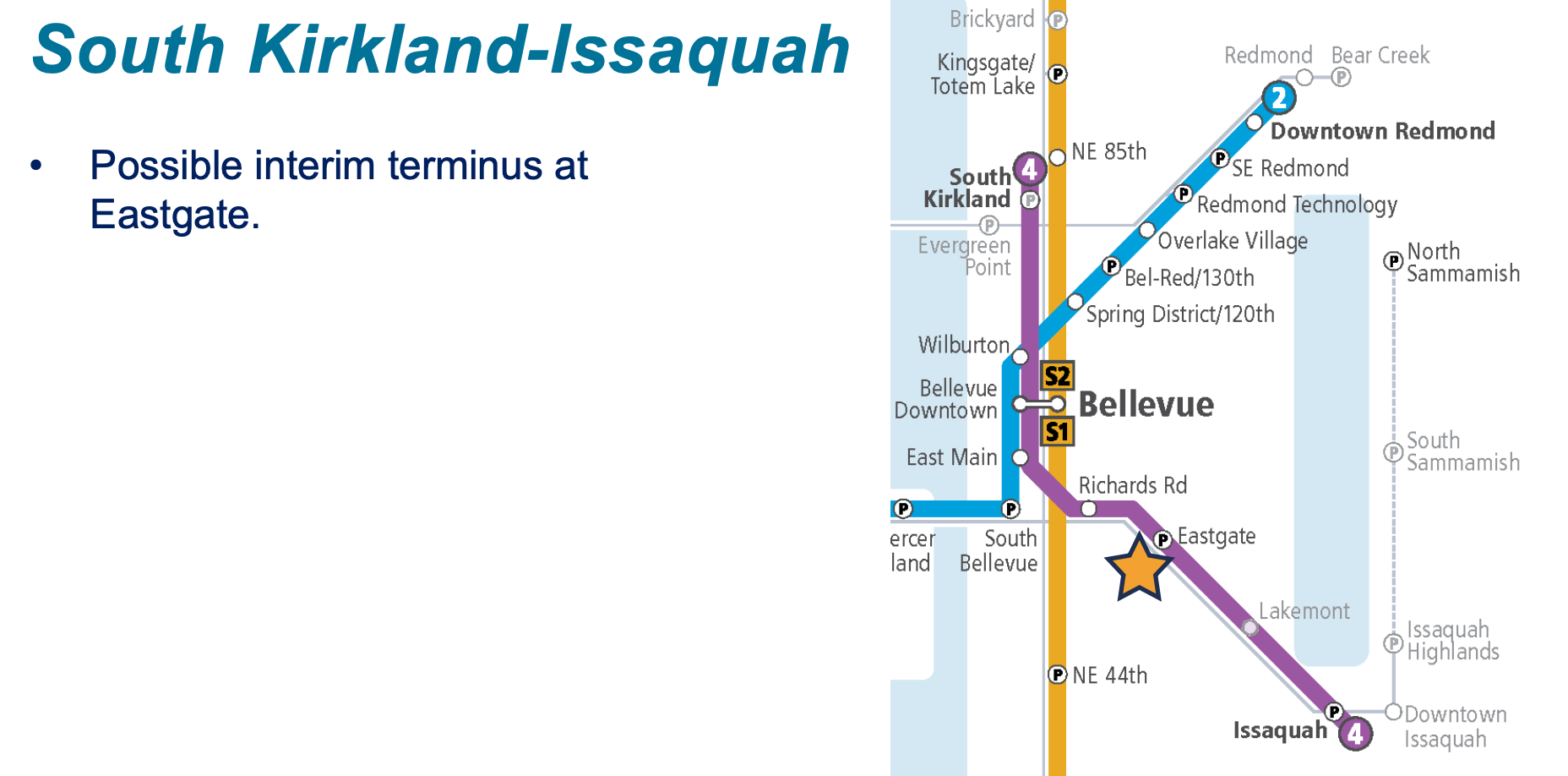

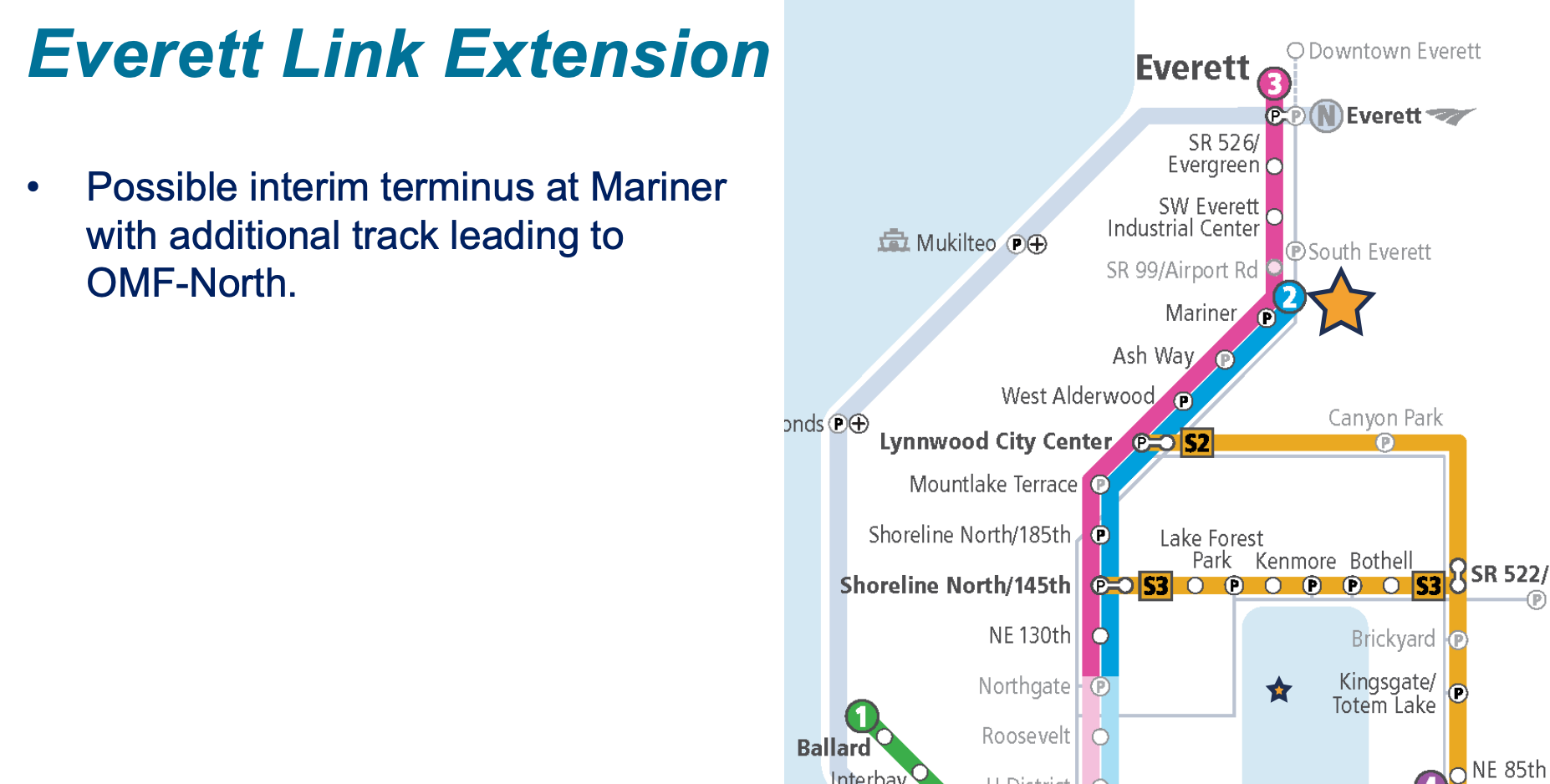

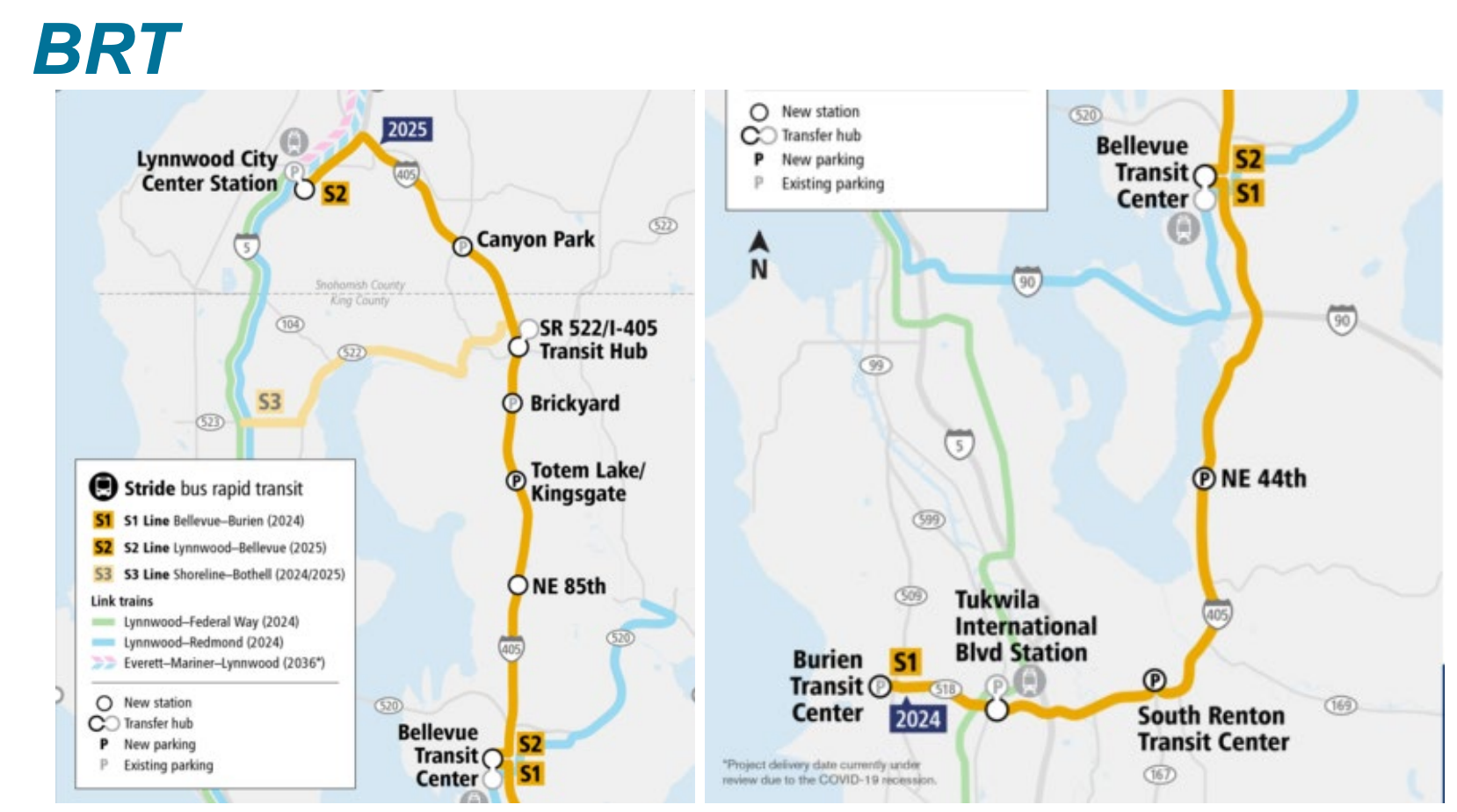

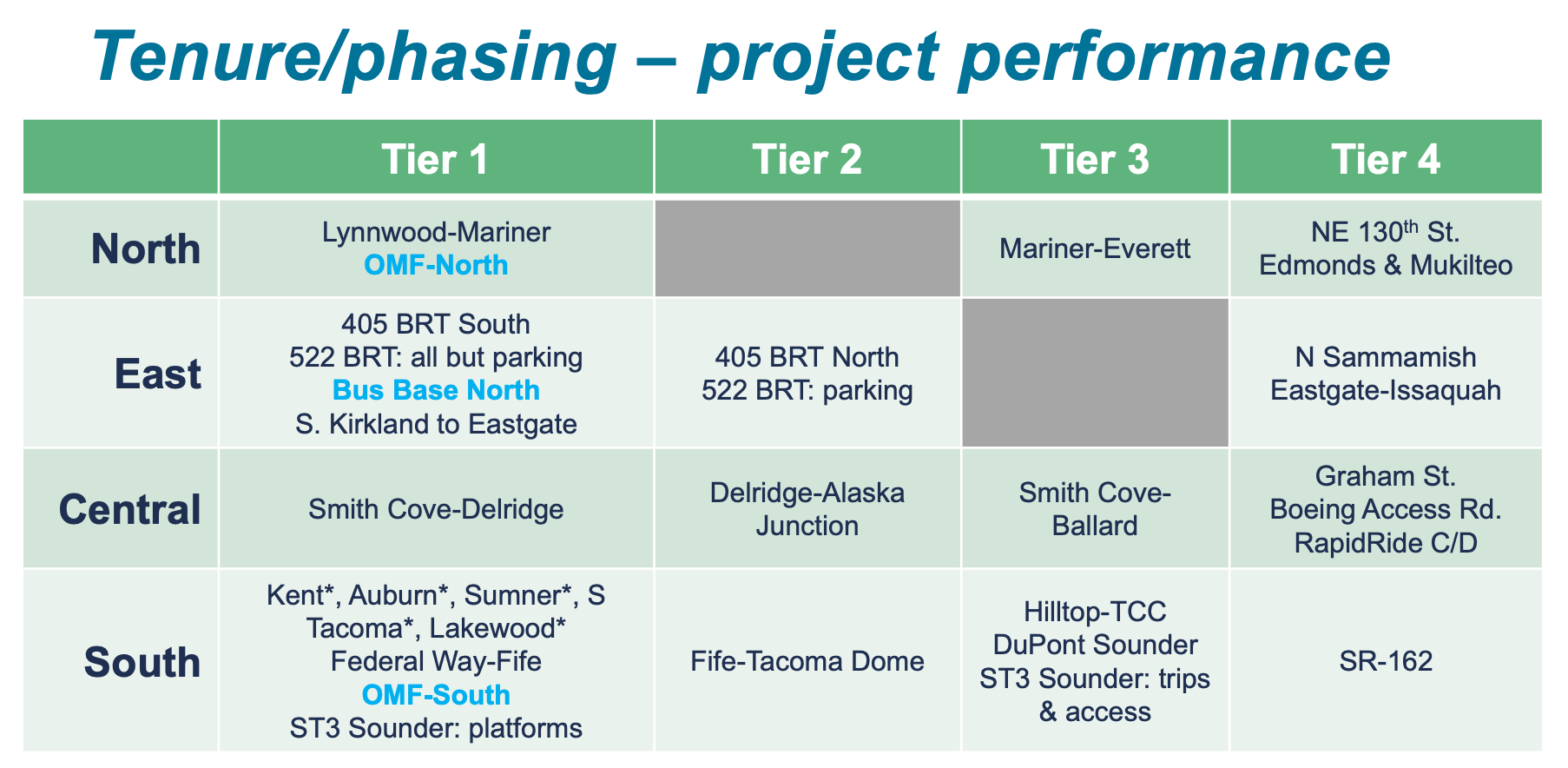

Each scenario first looks at a specific criterion. So on the basis of ridership, for instance, a project’s performance is analyzed by the kind of ridership it is expected to deliver for scoring and then packaged into categories. Sound Transit has packaged together functionally related projects. An example is the Everett Link extension that necessitates a new operations and maintenance facility. Without that element, the extension could not be delivered so it gets wrapped into a package. The same principle applies to the three Stride bus rapid transit (BRT) projects which require a new bus base. Those are four distinct projects, but functionally are one package, though individual Stride lines could be parsed out and delayed.

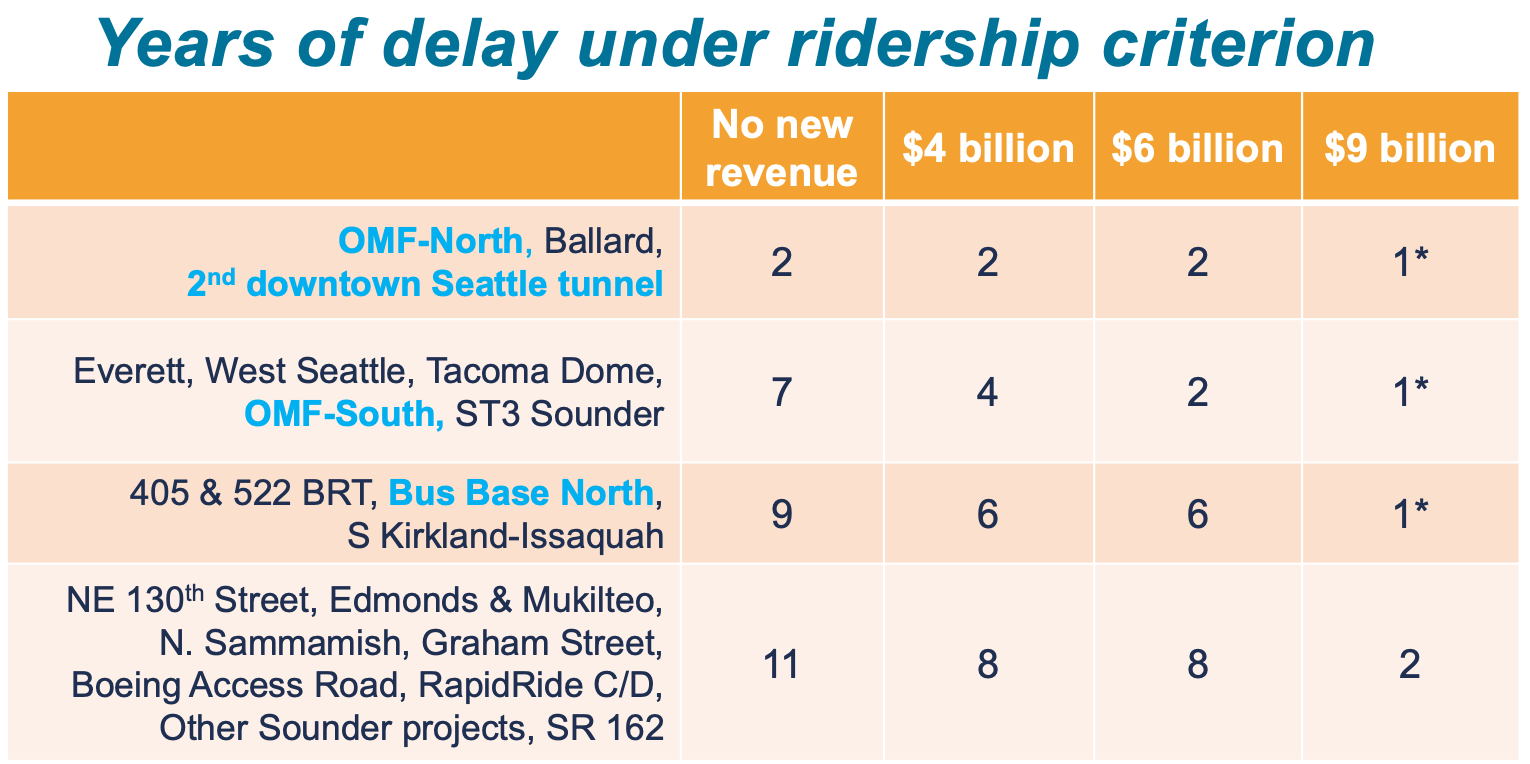

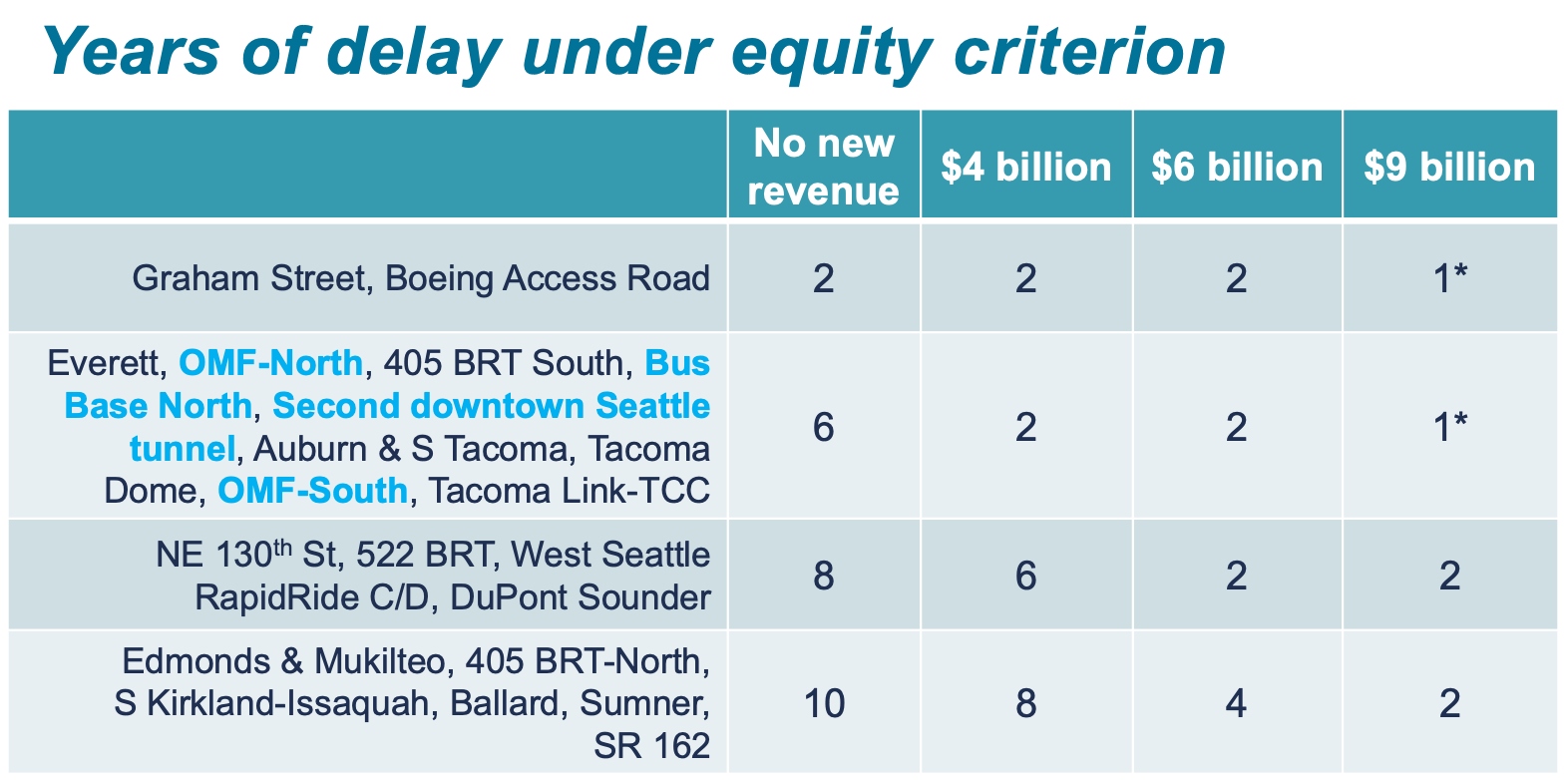

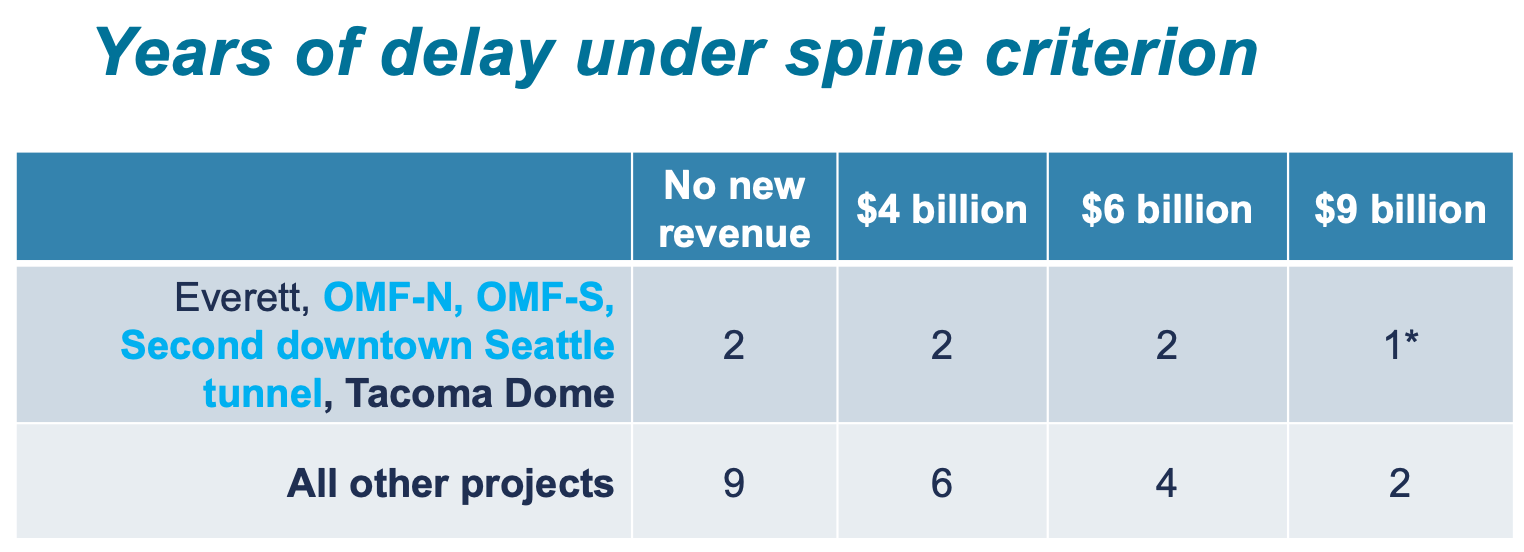

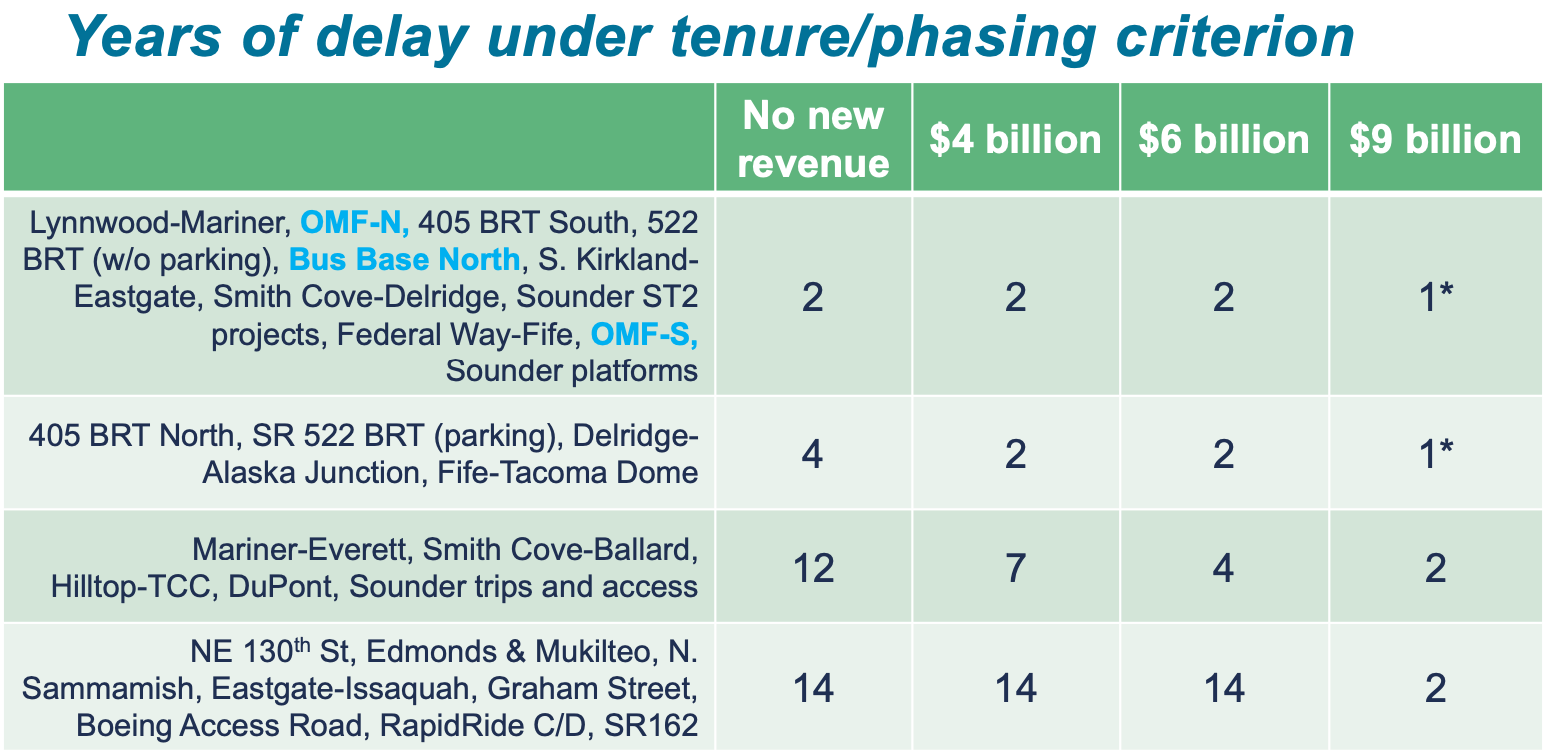

Additionally, each scenario uses revenue assumptions to create four sub-scenarios showing how many years of delay may apply to a package of projects. The baseline sub-scenario, or plan-required approach, assumes no new revenue or capacity would be provided. The alternative sub-scenarios assume $4 billion, $6 billion, and $9 billion in additional revenue or capacity, respectively. This does not necessarily mean that new revenue would need to be raised since project scope could be reduced or other project savings might be found.

The latter three alternatives are consistent with the expanded capacity approach that King County Executive Dow Constantine championed last summer.

None of the scenarios individually presented will form the final alternative that the board may choose later this year. In part, that is because the board is legally obliged to meet multiple objectives of the Sound Transit 2 and 3 plans. The scenarios do not achieve and do not account for specific subarea equity impacts. Agency staff presented the scenarios mainly for illustrative purposes to get the board thinking about tradeoffs at this point in the process.

As a note to the following scenarios, projects that are highlighted in blue require significant system investments to support them and asterisks in the delay tables indicate that current pandemic-related project delays may impact timing and make the indicated delay unachievable.

Ridership potential scenario

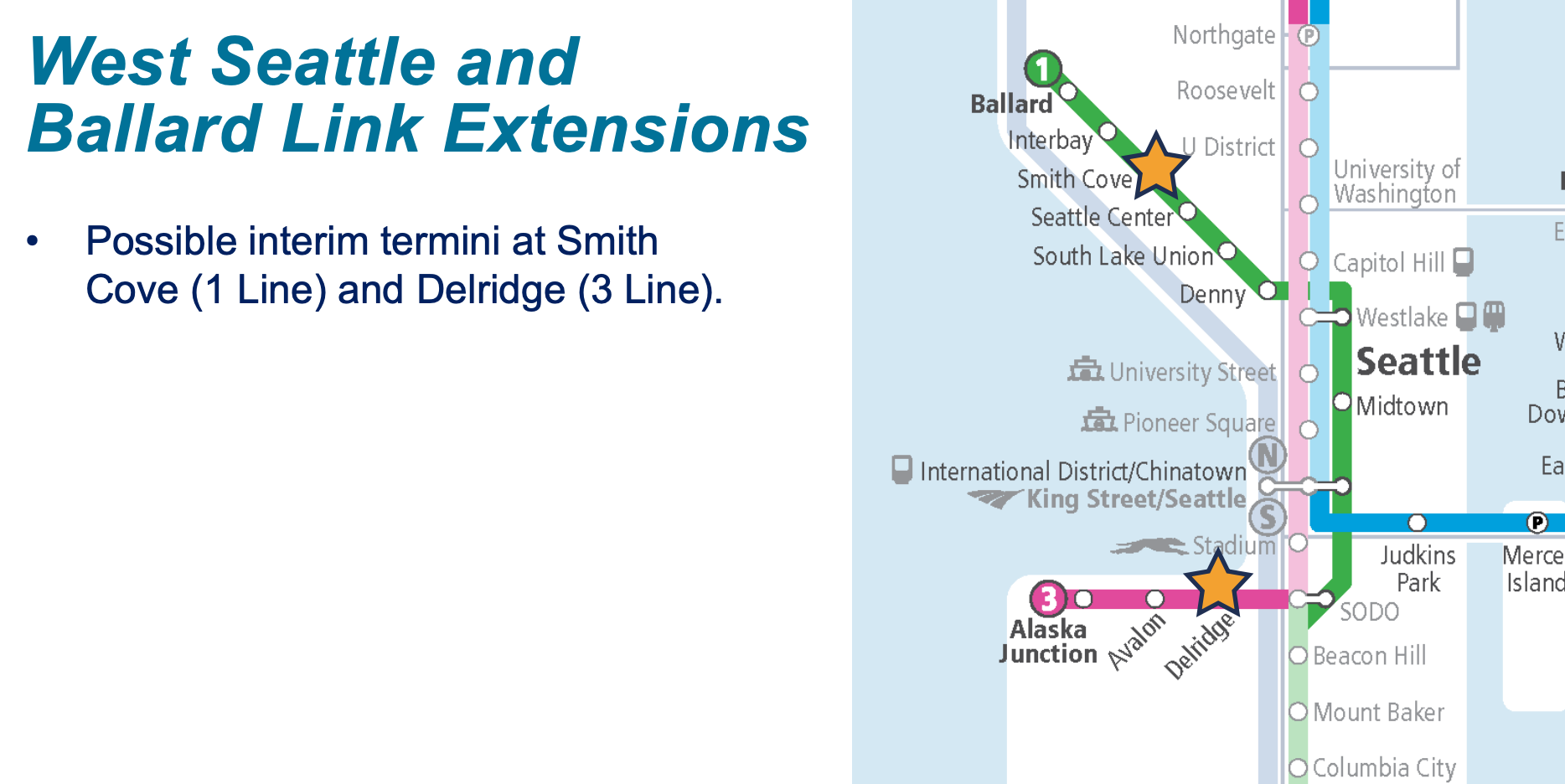

The daily ridership potential scenario is premised on four tiers of ridership. Tier 1 on the high end bundles several projects into one mega project serving 45,000 daily riders. The Ballard Link extension, second Downtown Seattle transit tunnel, and Operations and Maintenance Facility North–all individual projects–are functionally dependent upon each other so they all are identified as the Tier 1 project. Tier 2 has several projects in different geographic areas, some of which are functionally-related but some that are not. Projects in the tier are estimated to serve 23,000 to 45,000 daily riders. A smaller subset of modest scope projects fall into Tier 3 with the Stride projects being functionally-related. Sound Transit estimates that Tier 3 projects will serve 5,000 to 23,000 daily riders. Rounding the tiers is Tier 4 which is mostly smaller bus projects, Sounder commuter rail projects, and station access and parking projects. Among this group, too, is three Seattle light rail infill stations and RapidRide C and D Line upgrade projects. Sound Transit assumes that these projects will serve fewer than 5,000 daily riders.For the Tier 1 projects, delivery would be close to the baseline plan. They would only be delayed one to two years depending upon whether or now financial capacity is expanded. Moving down the tiers though, delays begin to balloon quickly under the scenarios when less than $9 billion in additional financial capacity is analyzed. The Tier 4 projects get hit hardest with as much as 11 years of delay. Tiers 2 and 3 are not all too far behind in the worst-case scenario with seven- and nine-year delays.Equity scenario

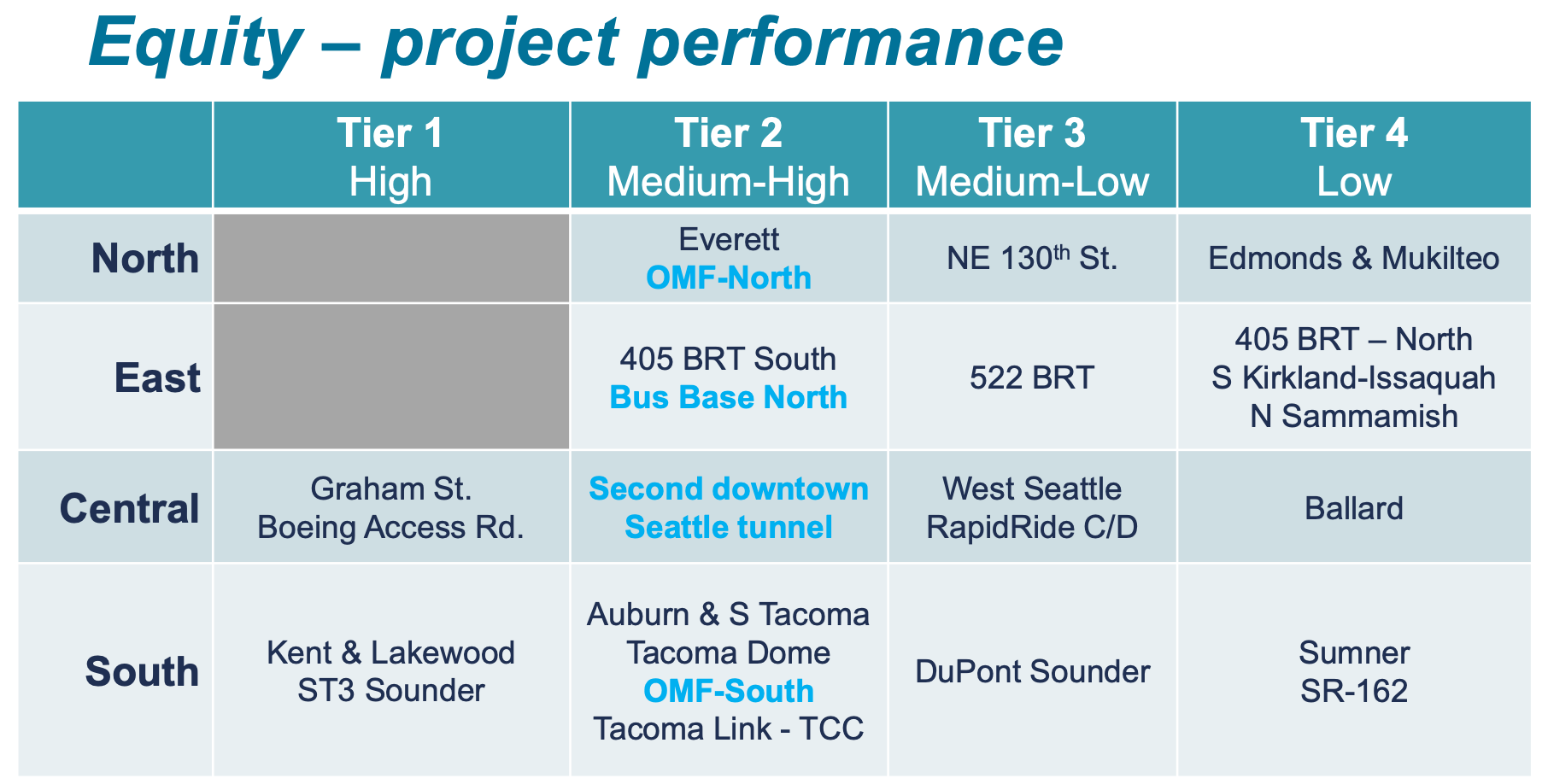

Under the equity criterion, Sound Transit has also identified four tiers that are predicated on projects that prioritize communities of color and low-income communities within one mile of a project. The analysis does not look at those communities that might be further than one mile from a project but might still access it by bus or other means. Projects that fall into Tier 1 for high equity include the two Southeast Seattle infill light rail stations, two station access and parking projects (Kent and Lakewood), and Sounder commuter rail improvements. Tier 2 medium-high equity projects tend to support a smattering of projects in areas north and south of Seattle, leaving out the Eastside and most of Seattle. Tier 3 medium-low equity projects focus on a mix of bus, Sounder, and smaller Seattle light rail projects. Tier 4 low equity projects are rounded out with the Ballard Link extension, Eastside projects, and station access and parking projects in wealthier suburban communities.Delivery of Tier 1 projects would one to two years behind schedule under the varied financial capacity scenarios. Tier 2, Tier 3, and Tier 4 projects could ramp up to as much as six, eight, and ten years delay, respectively, without additional financial capacity. But an infusion of $6 billion of additional financial capacity could keep delays to two to four years and $9 billion of additional financial capacity could keep all projects within one to two years of delay similar to the ridership potential scenario.Completing the spine scenario

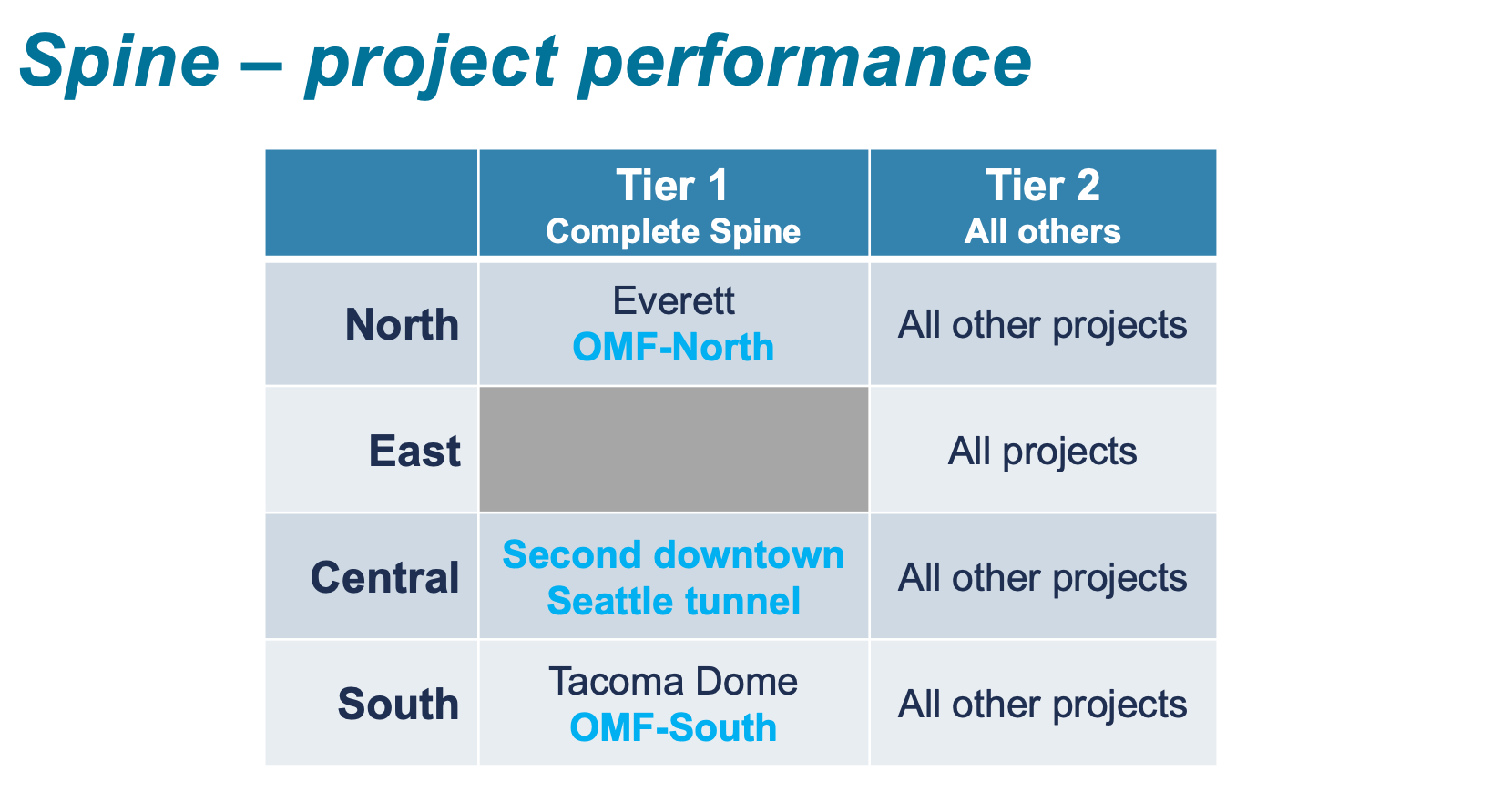

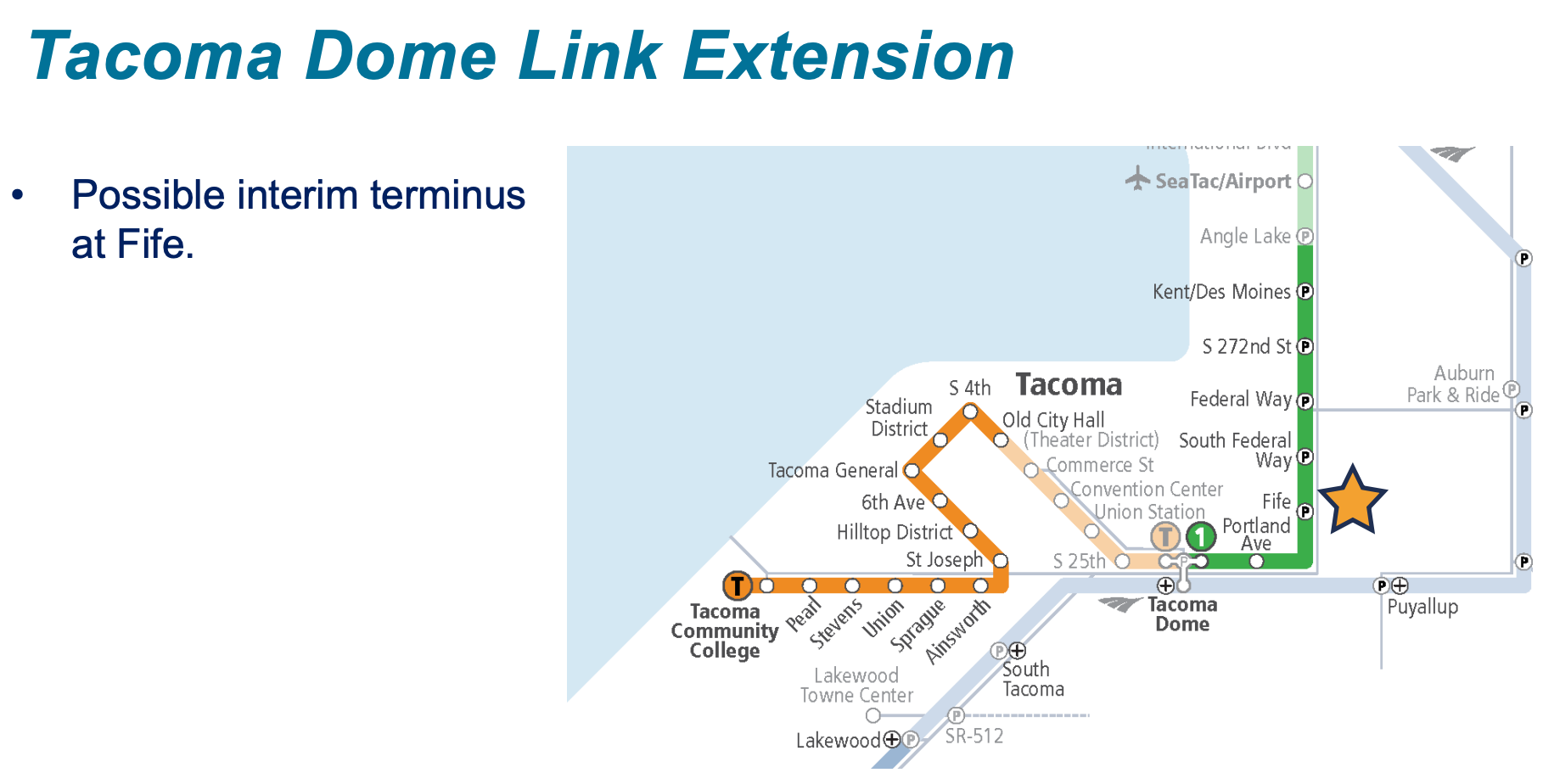

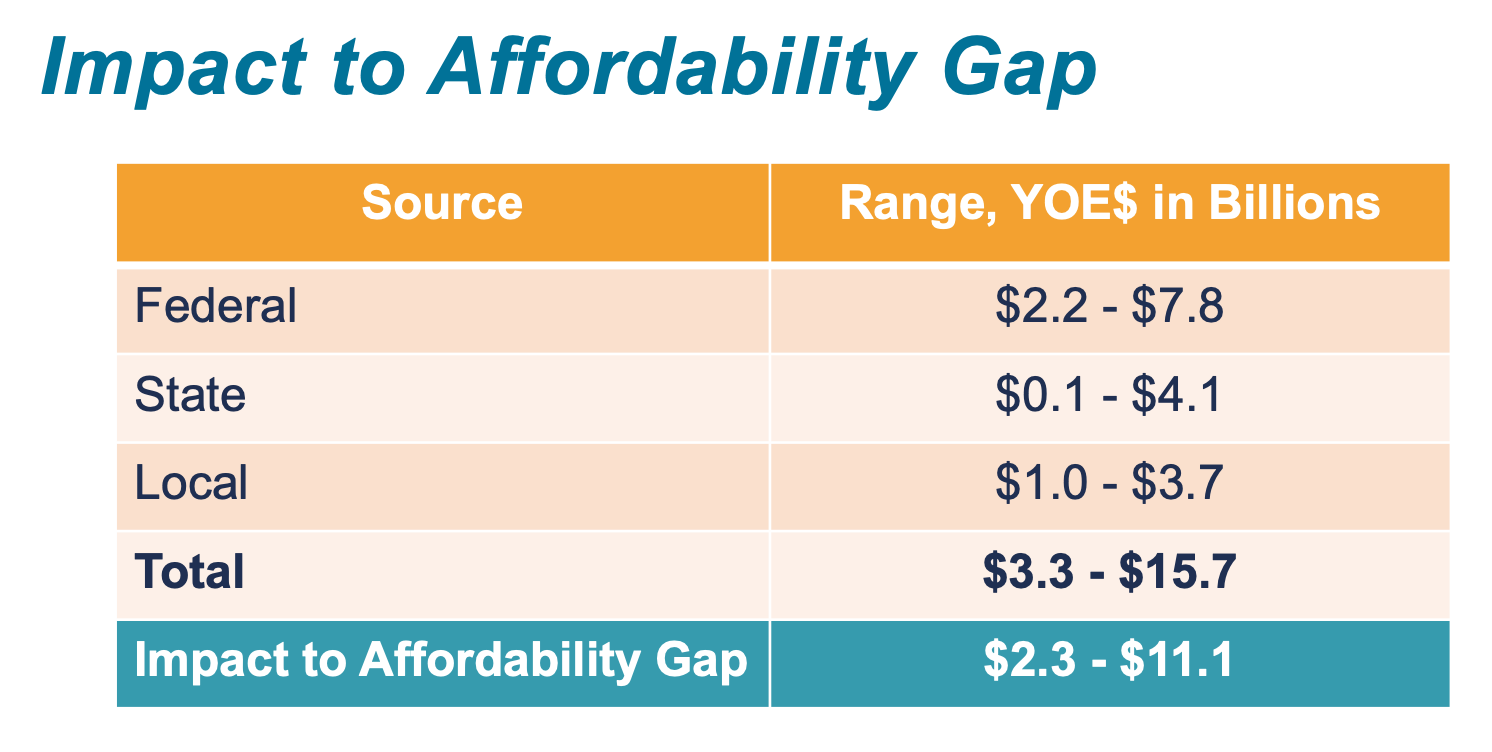

The completing the spine scenario is principally focused on delivery of light rail to Everett and Tacoma. This requires several other projects besides those light rail extensions to be packaged together, including the new northern and southern operations and maintenance facilities and the second Downtown Seattle transit tunnel. This scenario only has to tiers with the aforementioned projects forming the first and all other projects forming the second.With $9 billion of additional financial capacity, the completing the spine projects could be delivered with only a year of delay. With less or no additional financial capacity, the project could still be delivered with only two years of delay. Additional financial capacity primarily affects all of the other projects which would range from two to nine years of delay depending upon how much additional financial capacity is provided.Tenure and phasing compatibility scenario

Tenure and phasing compatibility scenario is notably more complex than the others since it combines two criteria into one with a scattershot of projects across tiers and areas. According to an adopted resolution, the criteria are supposed to ask: “How long have voters been waiting for the project?” and “Can the project be constructed and opened for service in increments?” This scenario is interesting in that actually splits apart some projects like the Tacoma Dome and Ballard/West Seattle Link extensions. Ballard and West Seattle Link, for instance, become Smith Cove-Delridge, Smith Cove-Ballard, and Delridge-Alaska Junction, which are three distinct extension projects.Without getting too deeply in the organization of tiers, there are some projects that appear to rank low despite being very long-awaited projects. Examples of that are the Graham St. and Boeing Access Road light rail stations that were both Sound Transit 1 provisional projects. Likewise, the RapidRide C and D Line projects should be on the same schedule as the BRT projects, but somehow falls two or three tiers behind. On the flip side, all of the Ballard/West Seattle Link extension projects rank ahead in the tiers. The degree to which the projects and tiers have anything to do with the tenure seems tenuously connected to reality and really more to do with phasing.Consistent with other scenarios, the Tier 1 projects would only be delayed one to two years. Tier 2 projects fall a little further behind with one to four years of delay depending upon additional financial capacity. Beyond this, tiers quickly see delays rise as much as 12 years for Tier 3 and 14 years for Tier 4. However, the primary benefit of this scenario is that Tier 1 and Tier 2 projects can make major progress on big project in all subareas. Despite the pressure it puts on delay for other projects in the lower two tiers, this could give the agency time to come up with new revenue options to solve for those projects, possibly reducing their delays, too.Affordability gapThe affordability gap remains around $11.5 billion through 2041, which is the base program period. An independent audit should come out in March that looks at program costs and the affordability gap further. That review could push the gap in either direction. Then in April, the agency plans to update revenue estimates, conduct a final cost estimate update, and revise the affordability gap update. This will be used in developing capital expansion program realignment alternatives.Agency staff have identified several ways that the affordability gap could be addressed through additional revenues without raising taxes or legal debt capacity.On the federal level, the agency has identified five primary tools to raise additional revenue:

- $1.5 billion to $4.5 billion in new federal Full Funding Grant Agreements (FFGAs);

- $1.9 billion from Moving Forward Act that would increase the federal share of existing FFGAs;

- $195 million from President Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan using formula grants;

- $180 million to $200 million from the American Rescue Plan through Capital Investment Grants; and

- $500 million to $1 billion by better federal loans terms.

At the state level, agency staff identified three primary paths:

- A direct grant through state transportation appropriations ranging between $46 million and $3.8 billion;

- Modifying state law to allow Sound Transit to receive mobility grants which could net between $50 million and $166 million; and

- Reducing the fees that Sound Transit is charged by the Washington State Department of Revenue (DOR) for tax collection, which could save $137 million.

Sound Transit has reason to believe that it is being overcharged for state tax collection.

On the local level, agency staff have also identified three tools:

- Pursuing a regional vote within the taxing district to increase the debt capacity limit, which would free up anywhere from $1 billion to $3 billion in debt that could be issued without increasing taxes and fees;

- Enacting a voter-approved business tax of up to $24 per employee per year, which could net up to $685 million; and

- Increasing the rental car tax to net up to $71 million.

Together, these measures could significantly close the affordability gap, shrinking it somewhere between $2.3 billion and $11.1 billion. While new revenues could be as much as $15.7 billion, which is higher than the affordability gap, there is a “mismatch” between when the new revenues might be raised and when capital expansion program expenditures are made. That means that additional revenues would be somewhat less impactful to outlay costs that the agency is taking on. Nevertheless, if the affordability gap could be narrowed to $11.1 billion, that would virtually solve the problems that the agency is facing with only minor project delays.

The capital expansion program realignment process will continue through July when the board will make final decisions on a plan. In the meantime, the agency will work through a framework for realignment, seek feedback from the public, and develop alternatives.