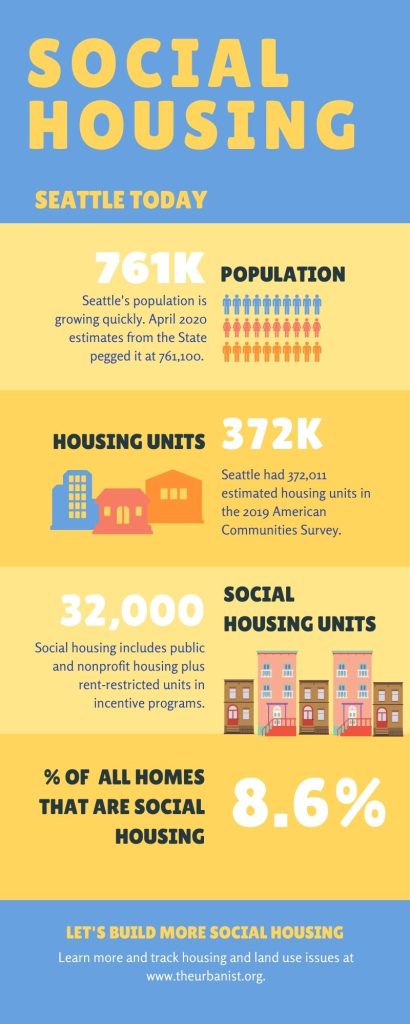

Social housing composes 8.6% of Seattle’s housing stock, which is well below many peer cities around the globe. Some standouts are far ahead. In Singapore, that number is around 80% and in Vienna it’s more than 60%. Other cities are gaining ground fast. Paris is on pace to hit 25% social housing by 2025, and 30% by 2030.

Seattle is picking up the pace of production for social housing, but so too are market-rate developers. That means the social housing percentage isn’t projected to increase much, barring further investments. Social housing encompasses several forms of affordable housing including public housing, nonprofit housing, and rent-restricted homes in market-rate buildings offered via incentive programs like inclusionary zoning. There’s a really strong case Seattle should be building more social housing than it is. Doing so would combat displacement and shrink commutes for working class people, who keep the city functioning and culturally vibrant. Social housing investment would engender mixed-income neighborhoods rather than Seattle slipping into a one-class city of the rich.

“Everyone should have the possibility to live in Paris,” Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo said during her last election campaign.

Hidalgo has pointed to retaining working class residents as the impetus for Paris’ social housing program, without which those folks would be increasingly priced out and pushed out. “To help retain those low- and middle-income residents, Paris has been creating upwards of 7,000 units of new social housing a year under Hidalgo (up from roughly 5,000 a year under Delanoë), for a total of more than 100,000 units added since 2001,” Colin Kinniburgh reported in France24. “It has achieved this through a combination of new construction, conversion of existing buildings and, to a lesser extent, simply buying apartments to take them off the private market.”

What would it take for Seattle to achieve a social housing triumph similar to Paris? Starting just shy of 9% social housing, we have a steeper climb. Nevertheless, the route is open to us if we’re willing to commit, and the need is great.

“We as a city need to do more,” said Mary Steele, Interim Executive Director of Compass Housing Alliance. “Affordable, permanent housing is the foundation for a stable life and the need in Seattle keeps climbing year over year.”

Social housing today

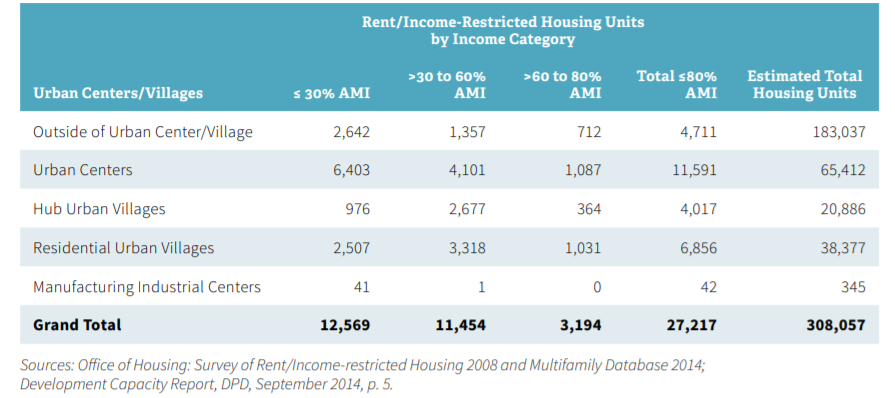

In 2015, the Seattle Office of Housing (OH) estimated the city had 27,217 social housing units in the Seattle 2035 Comprehensive Plan, and 80% of them were in designated Urban Centers and Villages. In fact, Urban Centers (the Downtown core, University District, and Northgate) accounted for 42% of the city’s total–11,591 social housing units. While there is a popular conception that Downtown is only for the rich residents, that’s not the full story–in fact much of the our social housing stock is there. Urban Villages hosted another 10,873 social housing units. The rest of the city, which is predominantly single-family zoning, accounted for just 4,711 social housing units, meaning just 2.5% of housing in these zones.

Miriam Roskin, Acting Communications Manager at the OH, said OH through its partners has increased the social housing portfolio by more than 5,000 since 2015, pushing Seattle past 32,000 social housing units. Investments announced in December 2020 will add 1,285 social housing units and preserve another 154 units.

Top social housing sources in Seattle

- Seattle Housing Authority: 8,000

- MFTE: 7,117

- Bellwether: 2,100

- Community Roots: 1,600

- DESC: 1,400

- LIHI: 1,300

- Plymouth: 1,027

- Catholic Housing Services: 833

- All sources: 32,000+

That social housing production must hold surf in a city where market-rate production is also robust. Seattle had 372,011 housing units according to the 2019 American Communities Survey. In the last three years, Seattle has built about 10,000 new homes per year. Growth has been overwhelmingly via apartment buildings in the city’s Urban Centers and Urban Villages, planning designations with the most permissive zoning and land use codes that compose less than a tenth of the city.

Imagine the housing options we’d have if “urban villages” were the norm instead of the exception. Social housing providers would have a lot more room and less intense bidding wars if that were the case. More of the city would be open to social housing and people priced out of market housing.

Hitting 20% social housing by 2040

Perhaps it’s easier to think about social housing targets via a few benchmarks. To reach 15% social housing, we would need 75,000 of 500,000 total units to be social housing. Working from our latest tallies of housing stock, that’d mean adding 43,000 social housing units and 85,000 market-rate homes. If we assume this takes a decade, that means adding 12,800 homes per year, with 33% of it social housing. This jump in social housing production to a 4,300 annual pace can’t happen immediately, but it is an obtainable goal in the medium term. For example, Seattle could reach 4,300 social homes per year with a mix like this:

- 1,000 via the Seattle Housing Levy (due for renewal in 2023 and should be doubled or tripled in size);

- 1,000 via big business taxes like Jumpstart Seattle;

- 1,000 via Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program–Seattle’s version of inclusionary zoning;

- 800 via the Multifamily Tax Exemption (MFTE) program, which grants property tax breaks in new buildings that set aside a certain number of units (typically a quarter) as moderately affordable; and

- 500 from the Real Estate Excise Tax (REET) and county and state programs.

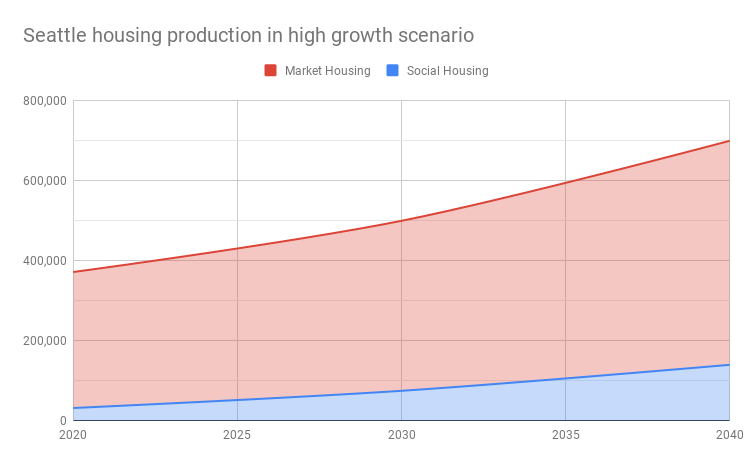

Getting to 25% social housing would require ramping up production even more. Reaching a benchmark of 140,000 social units out of 700,000 total homes would be 20%. To do this in a decade from the 15% benchmark could be achieved by keeping the one-third social housing mix of new production and adding 20,000 total homes per year.

For recent Seattle standards, this would be breakneck production, but the feasibility of growing this fast is boosted by the fact social housing production can rise above the slumps and busts in the private market and smooth them out. With one-third of Seattle’s housing production henceforth being social housing in this scenario, the countercyclical building capability would be pretty significant. The graph below shows this scenario of hitting 700,000 homes by 2040 with 20% social housing.

A 25% mark, meanwhile, could be hit by hitting 200,000 social housing units by the time Seattle has 800,000 homes or 250,000 by the time it has one million homes. The scenario laid out is a lot more aggressive than the conservative growth targets in the Seattle 2035 Comprehensive Plan. The planning document predicted just 70,000 new households by 2035, and at least half of that estimate has already happened in just five years. That inspired the more ambitious goals enumerated below.

The passage of MHA rezones in all Urban Centers and Urban Villages has increased Seattle’s housing capacity while also creating affordable housing via all new commercial and multifamily projects. Because the MHA affordability requirements are tied to the intensity of the zoning capacity increase, Seattle could upzone further to increase the requirement. The fact that single-family zones, which consume three-fourths of buildable land, are exempt from the MHA participation is a further oversight. As it stands, the existing MHA program will be a significant boost.

“As to longer-term plans, both the Seattle Housing Levy’s rental housing and MHA programs establish production goals,” Roskin said in an email. “The Levy’s seven-year rental housing production goal (through 2023) is to add 2,150 units. We are well on track to exceed that goal. The MHA program’s 10-year goal is to support production of 6,000 new units. The program is still ramping up, but as noted in the 2019 year-end report covering MHA and predecessor programs, MHA payment proceeds from the first full year of implementation supported six projects (844 units) that received Office of Housing funding awards in 2019.”

Why social housing?

The benefits of social housing are significant and setting an ambitious social housing target isn’t about bragging rights. It’s about making Seattle a better city and increasing quality of life for all people, not just the rich. As it stands, Seattle is deeply unaffordable for households not pulling in six-figure incomes.

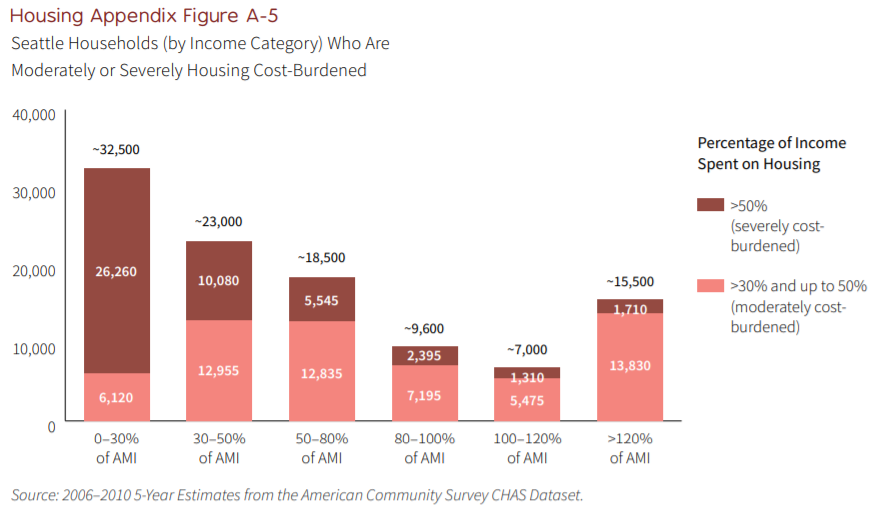

Back in 2015, the City calculated 21% of renter households are severely cost-burdened, spending more than 50% of their household income on housing costs. Housing costs only continued to jump in the following years. Those statistics lend support to the idea of Seattle targeting at least 20% social housing. No household would need to be severely cost burdened if sufficient social housing existed. Freed from their rent burdens, working class folks would pump money into the economy, invest in education, business ventures, cultural creation, and their personal wellbeing.

With the housing crisis already in full swing, the Covid-19 pandemic and recession added a new threat and devastated many working class households in Seattle. For households who lost income, severe rent burdens could turn into a wave of displacement and evictions after the City lifts the eviction moratorium.

Likewise, the suburbanization of poverty was already a growing issue in Seattle and many other booming cities before Covid added further disruption and displacement pressure. Social housing in the urban core counteracts the problem. Beyond cutting housing costs, it also helps working class households reduce their transportation costs by putting them in walkable neighborhoods close to amenities and the heart of our regional transit network, as opposed to car-dependent suburbs with spotty transit access.

Covid impacts

To make matters worse, Covid disrupted plans for social housing investments as Roskin alluded to in her comments.

“The Council’s spending plan [for JumpStart Seattle] cites a preference for 62% of those funds to be allocated to Housing and Services starting in 2022,” she said. “As we saw last year, COVID-19 devastated city budgets around the globe, and Seattle was not immune.”

Social housing builders are also adapting to pandemic realities. Plymouth Housing spokesperson Lenna Mendoza said the organization altered its plans to respond to the crisis.

“In 2019, we launched a capital campaign to raise funds to grow out our portfolio. Our original goal was eight buildings (~800 units), but we ended up closing the campaign early so we could focus on supporting staff and residents through COVID-19,” Mendoza said in an email “This brought the number of new buildings to six, one of which had already opened, and is included in the above total. The other five buildings are currently in our development pipeline, for a total of 487 units on the way. All together these five additional buildings will bring Plymouth’s unit count to 1,514 units across our 20 buildings by the end of 2023. Only one of those buildings will be outside of Seattle, in Bellevue. That property will have 95 units, so our Seattle-only total for 2023 will be 1,419.”

The pandemic has also underscored the need for social housing, as Seattle OH Director Emily Alvarado noted in December.

“We must do more than a craft a housing response to this crisis that does more than return Seattle to the status quo,” Alvarado said. “We must both stabilize renters and homeowners now and embrace a long-term vision for housing justice that’s rooted in racial justice. The investments we announced today are not sufficient to solve Seattle’s affordability crisis, but these investments reflect our commitment to act with urgency and undo failures in the existing housing system.”

Having a safe home with good ventilation has become even more essential to public health in an era of airborne viral loads and wildfire smoke. Stable affordable housing helps families weather financial crises instead of exacerbating them. highlighted the build back better element

Social housing builders are seeking to rise to the occasion–Bellwether and Community Roots each say they have about 1,000 social housing units in the pipeline to lead the charge, but many others have upped production too. Among this new wave is Seattle’s first affordable highrise in over 50 years, which is a partnership between Bellwether and Plymouth in First Hill. Still, the city, county, state, and federal government should all be investing more to address the housing crisis.

Hitting 20% social housing in twenty years is doable, but it’s going to take a moonshot effort. A series of smaller steps can build momentum, like doubling the housing levy in 2023 and taking MHA truly citywide by ending apartment bans in all residential zones during the 2024 Comprehensive Plan update. This would make inclusionary zoning apply citywide, meaning all market-rate housing would generate social housing too. Bigger upzones would also mean bigger affordability requirements.

Taxing the rich to fund social housing is likely to be the central battle. It also happens to be a powerful tool to combat wealth inequality and heal the damage racism has inflicted on the generational wealth of Black, Indigenous, Latino, and Asian communities for far too long. The JumpStart corporate tax was an important step in that direction and proved progressive taxation in Seattle was possible even with our restrictive state laws and the entrenched local capitalist elites.

With our politics here (and everywhere) at risk of falling victim to small-minded and fear-based appeals, the salve is to dream bigger and relentlessly execute on bold progressive vision. The idea that everybody has a right to the city regardless of race, gender, age, and socioeconomic status is big enough to cut through the noise. So, let’s get chasing that vision.

This article has been updated with Emily Alvarado’s quote.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.