When it comes to the spotlight for transportation projects and upgrades, buses never get the publicity. To most, a bus is boring. It is a system that is simply there and goes rather unnoticed. Flying cars, autonomous vehicles, drones, hyperloops, and electric vehicle tunnels are all the rage. In Seattle, with so much attention rightfully paid to the expansion of light rail, sometimes we forget about the network we already have and do not realize what it can become.

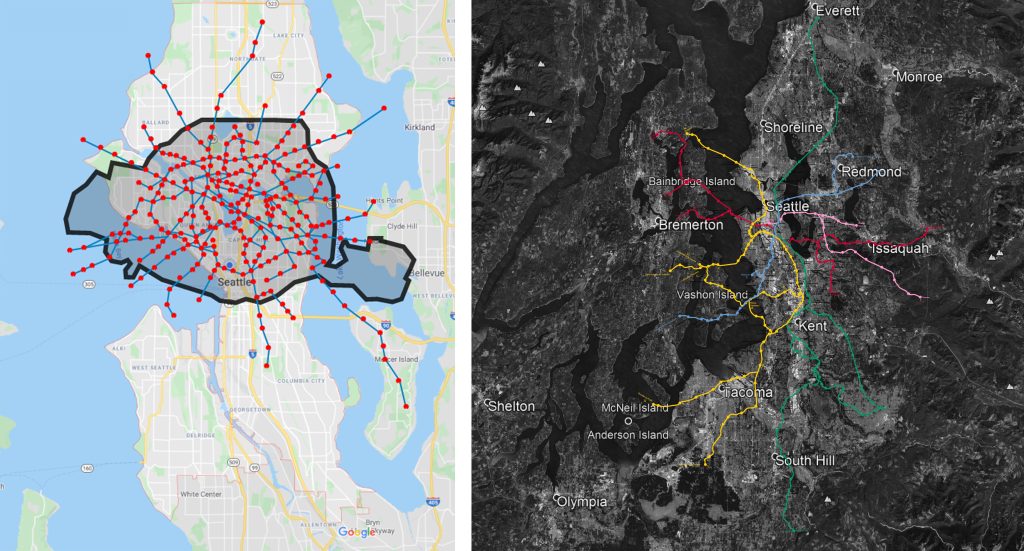

One of the unique things about transportation expansion in America is it tries to do too much. Link is in a complex situation as it connects suburban commuters along a 75 mile spine and operates as the urban system all at once. In Paris, they have two separate transportation systems: the urban rail network of the Métro and the suburban commuter rail network known as the Réseau Express Régional (RER). So many cities in the United States–Seattle included–are not set up to justify the expense it would take to build an urban only subway system. It would lack funding, political will, and ridership. That is why the Greater Seattle Metro area had to build a light rail network from Tacoma to Everett, to get the funding and the votes. King County Metro runs buses across the region as well, with over 100 lines in Seattle itself. This system covers 90% of the city already with frequent walksheds and hasn’t even begun to reach its full ridership potential.

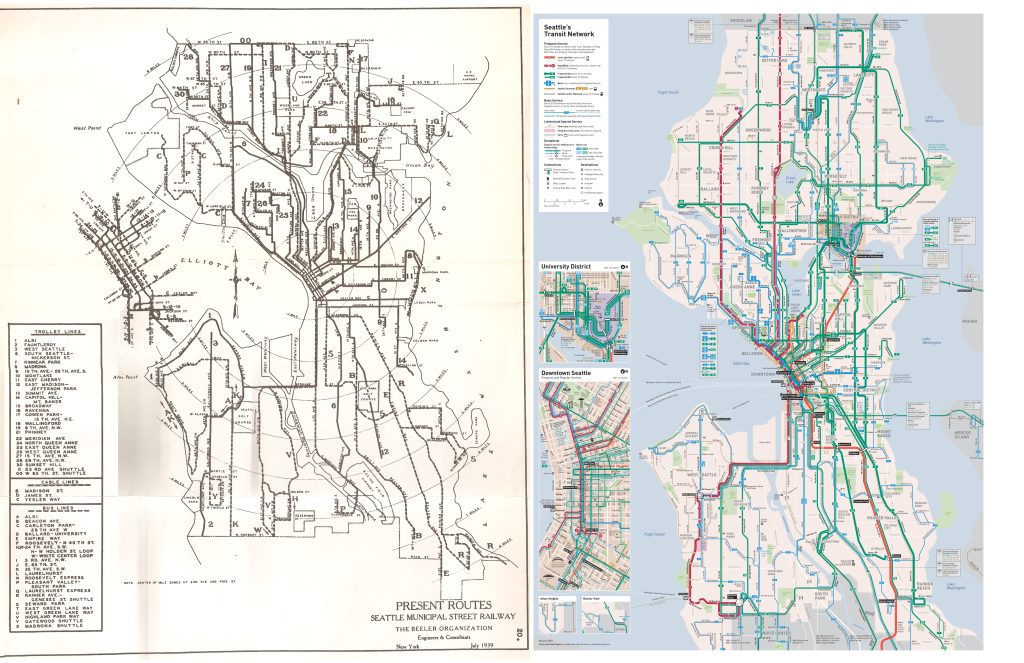

When we look at our transit history, a lot of commentary is made about Seattle’s lost streetcar network, a network that connected nearly every neighborhood with a permanent rail system. We romanticize over photos of what once was and look back on the mistake of ripping up lines so we could pave the way for car commuting. But when we study the old streetcar map and our current bus map side by side, did we really lose the network or did we simply replace it? One benefit with buses is how quickly they can be planned. We can create new routes or modify existing routes with ease, and supply newer parts of our city in a short period of time. Plus, we have already seen how painful it is to connect our two downtown streetcar lines with gripes over cost and ridership, so why wage those battles with our basic urban network? Buses are quick to deliver and cheap to upgrade.

Metro’s RapidRide bus lines each carry daily ridership figures over 10,000. Among them the D Line carried 15,000 a day and the E Line carried 18,000 a day. These buses prove how powerful small upgrades are when we prioritize buses. With more than 100 bus lines in the city already, Metro’s system could carry over 1.5 million riders a day in Seattle alone if they all operated like the RapidRide system. The RapidRide system uses its own bus-only lane, allowing them to bypass suburban commuters stuck in traffic. With off-board payment, there is no more queueing lines and buses stop and go in a blink of an eye. When Route 358 was upgraded to bus-only lanes, higher frequencies, and a off-board payment system to become the E Line, ridership grew from 11,000 a day to 18,000 a day in five years. With higher frequencies, more people get on buses or can simply wait another minute for the next one to come. If Seattle chose to grow up and grow out of its suburban land use constraints, and become a denser city of two million people, our bus network could easily carry 15,000 a day per route and grow the system’s ridership by 300%.

Former Governor Christine Gregoire expects one million new residents in the state of Washington over the next 20 years. Stuck in her ways, she feels we need to build more cities and more networks to move these people around. I disagree with that. Seattle is 84 square miles and has more than plenty of land to house every single one of the expected newcomers. Land use problems aside, the city’s systems can easily handle growing by one million more people and doing so would allow these new Washingtonians the opportunity to use the systems we have and not worry about bulldozing more forests to build new cities or neighborhoods.

Leveraging our bus system locally frees up the light rail to operate more like a regional transit system, moving suburban commuters sustainably and much faster than by means of the car. The bus system should not be in competition with the light rail, but rather, supplement the network so we can rely on both systems, instead of one.

Upgrading bus routes is easy. Painting bus-only lanes is cheap. Adding buses to increase frequency provides flexibility as the rest of our neighborhoods begin to grow and densify. Bus system upgrades may not turn any heads like a new train will, and it may not garner the attention by adding more buses and throwing down some paint. But those cheap upgrades can go the extra mile.

Now, we just need to be a city of two million people. How we get there is for another day, another post. But for now, let us look at the assets we have and not try and reinvent the wheel.

Correction: This article was updated to replace a 1941 bus and streetcar map with a 1939 map that provides more clarity on historic streetcar lines.

Ryan DiRaimo

Ryan DiRaimo is a resident of the Aurora Licton-Springs Urban Village and Northwest Design Review Board member. He works in architecture and seeks to leave a positive urban impact on Seattle and the surrounding metro. He advocates for more housing, safer streets, and mass transit infrastructure and hopes to see a city someday that is less reliant on the car.