On Tuesday, State Representative David Hackney (D-11th Legislative District) introduced an exciting bill that could provide Seattle a path to extend rail expansions beyond Sound Transit 3 (ST3) and help avert severe delays in ST3 timelines threatened due to cost escalations and dips in revenue due to the pandemic.

House Bill 1304 amends existing City Transportation Authority (CTA), which was intended for Seattle’s monorail expansion ambitions, to fund grade-separated rail transit instead. The idea is that if the whole Sound Transit Taxing District, which extends from Everett to DuPont, is not prepared to go from ST3 to ST4 in the near future, Seattle should be ready to forge on and plan for the long-term. Fellow Democratic Representatives Liz Berry (36th Legislative District), Joe Fitzgibbon (34th Legislative District), Frank Chopp (43rd Legislative District), Nicole Macri (43rd Legislative District), Steve Bergquist (11th Legislative District), and Gerry Pollet (46th Legislative District) signed on as co-sponsors.

“It’s clear that Seattleites support smart, well-planned transit expansion,” Rep. Berry said. “HB 1304 makes it possible to plan for the long-term, ensure we have resources to build Ballard to West Seattle expeditiously, and expand these lines into other parts of our city.”

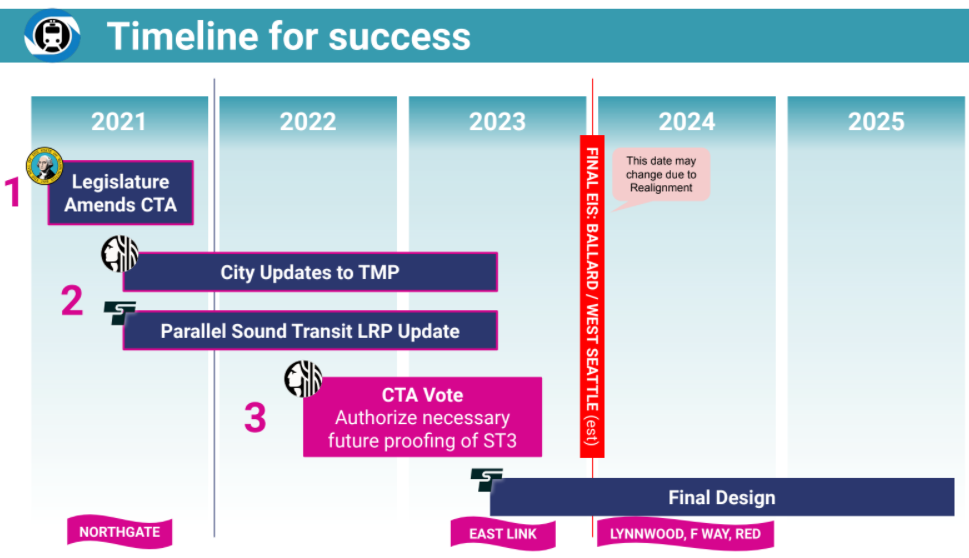

Seattle Subway has been pushing the bill behind the scenes, and has been a big proponent of planning ST3 for expansion and passing a ST4 package to keep building momentum. They have floated using the CTA as a funding source in the past, and this bill would clear the legal obstacles to doing so.

“Our district has some of the worst air quality in the state due to multiple highways cutting through our neighborhoods,” said Rep. Hackney said. ”South Seattle and South King County have the largest gaps in the region between transit service needs and transit provided, making life harder on essential workers still going to work in person. If we are going to solve these issues, make transit more equitable, and avert the worst of climate change, then we need to plan future rapid transit expansion now and find every opportunity to build rapid transit faster. HB 1304 is a key tool to do this.”

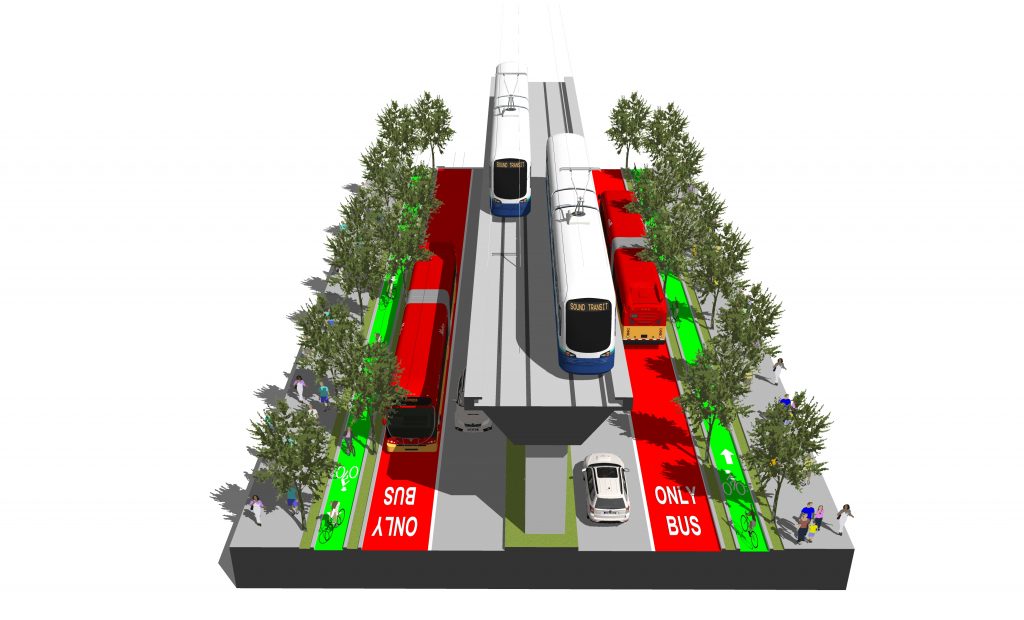

Having a voter-approved funding source for further expansion would allow Sound Transit to build ST3 with expandability in mind, Jonathan Hopkins, political director at Seattle Subway, said. As an example, Seattle’s second downtown transit tunnel could be planned to include a track turnoff toward Aurora Avenue for a future light rail line. Doing so would save a lot of future expense and the need to shut down service during construction, as we saw with 10 weeks of single tracking during East Link construction–dubbed Connect 2020.

“One of the inspirations for this bill was Connect 2020,” Hopkins said. “To shut down the system after you have it operating for 10 years is wholly unnecessary. They should have added a junction in 2009 when the light rail line wasn’t in operation when we shut down the tunnel. We knew we wanted to connect to Bellevue and Redmond. We knew we wanted to go across the floating bridge. We knew exactly where we wanted to do it. There just hadn’t been voter approval to connect there so Sound Transit couldn’t spend a dime because of a quirk in state law and their authorizing legislation.”

Hopkins said the bill would help rectify the issue. Moreover, a voter-approved expansion plan would also allow (and legally permit) Sound Transit to begin acquiring properties for stations and staging areas sooner, Seattle Subway said. Rapid jumps in property values are the biggest factor driving up costs over initial estimates, so acquiring land sooner could save hundreds of millions of dollars. The bill would not provide enough revenue to singlehandedly close the ST3 budget shortfall that has climbed to nearly $5 billion, but it would provide tools to control costs and promote better system planning going forward.

“[Sound Transit builds] what the voters tell them to, and not a penny more,” he added. “It’s all they’re allowed to do. It creates a bias that they extend rather than densify the system.”

Getting into the legislation

Chapter 35.95A RCW of state law governs City Transportation Authorities. The existing law only allows the performance of monorail functions by city transportation authorities—namely in Seattle. However, the bill would broaden that performance to grade-separated transportation function, and allow for the function of grade-separated transportation facilities to transport passengers. The bill defines those facilities as:

[L]ight, heavy, or rapid rail facility, monorail, inclined plane, funicular, trolley, or other fixed rail guideway component of a transportation system operating principally on exclusive rights-of-way that is not regulated by the federal railroad administration or its successor that utilizes train cars running on a guideway, together with the necessary passenger stations, terminals, parking facilities, related facilities, any lands, interest in land, or air rights over lands, or other properties, and facilities necessary and appropriate for passenger and vehicular access to and from people-moving systems.

From Section 1(7) of House Bill 1304

Existing language in Chapter 35.95A RCW distinctly excludes fixed guideway light rail system. This expansion is important because a CTA is a municipal corporation and an independent taxing authority. It would be an additional avenue for Washington cities to generate funding for light rail and other rail projects–potentially high speed rail— as long as the electors within the authority area approve of the taxation. Sorry gondola advocates, permitted use would be limited to station access in this bill and is prohibited in existing CTA law.

However, an important change is the increase of the population requirement of a city to have these powers. The language in the bill raises that threshold to 500,000 residents, up from 300,000. This would pull it even farther out of reach for Washington’s mid-sized cities like Spokane, Vancouver, and Tacoma. Those cities have populations that are all around 200,000, and could feasibly hit the existing text’s 300,000-resident requirement in the foreseeable future. If Spokane and Tacoma continue to grow at a more leisurely 7% per decade (like they did this past decade), it would be more than 40 years before they hit 300,000. Considering how fast Bellevue is growing (21% in the past decade), even it could be in play with the existing threshold–though much rides on zoning decisions.

Hopkins said upping the population threshold was intended to increase the bill’s chance of passing, but that he supports lowering the threshold if local legislators back it. This could be done in a future bill if they’re not ready to get onboard at this juncture.

“Expansion to include Tacoma in this law would further equity in the region,” Tacoma transit advocate Chris Karnes tweeted. “We need to allow qualified first class cities to get ahead of the growth. Transit plans and projects have a long gestation period already (20+ years).”

Legislators may have reason to lower the requirement to 200,000 residents if advocates win over their representatives. But, reading between the lines, it appears state legislators in places like Spokane, Tacoma, and Vancouver don’t want to bring the funding authority to their districts. Car tab increases, as a revenue option, are controversial in many districts outside Seattle.

Empowering Seattleites to build more rail

Here’s how Seattle could exercise these new powers if the bill passes.

Seattle City Councilmembers would be able to propose creation of an authority by ordinance, or a petition signed by 1% of qualified voters in a proposed authority area could propose an authority. The authority area can encompass a portion or the whole city. Backers would propose what kind of public grade-separated transportation function will be exercised by the authority and propose an initial array of taxes. The proposal would then have to be voted upon by the voters in the proposed authority area. If approved, the city councilmembers in the authority area would become the governing body of the authority and form the authority with bylaws and officers.

With approval of voters, the authority would have the power to:

- Levy annual property taxes of up to $1.50 per $1,000 of assessed value, a special yearly excise tax not exceeding 2.5% on the value of every motor vehicle (in 2002, a 1.4% tax was worth $1.5 billion for the Monorail Green Line), a up to $100 per vehicle license fee per year, and a 1.944% sales and use tax on rental cars–back of the envelope math suggests that these taxes and fees could raise $500 million or more per year if fully leveraged, primarily through the property tax;

- Issue bonds to borrow money;

- With its funding, the authority could acquire, lease, construct, add to, improve, replace, repair, maintain, operate, and regulate use of public grade-separated transportation facilities;

- Fix rates, tolls, fares, and charges for the use of facilities;

- Contract with other governments and private persons or corporations to design, construct, operate, or maintain facilities; and

- Establish local improvement districts and exercise all other powers necessary and appropriate to carry out its responsibilities.

New to these powers would be the ability to work with other transportation authorities like Sound Transit and public transportation benefit districts. Proposed changes would also allow CTA to negotiate and solicit competitive bids from private firms and corporations, establish offices, departments, boards, and commissions, appoint or remove officers and employees, fix compensation, employ specialized personnel, determine risks, hazards, and liabilities. Many of these new powers are spelled out to ensure that an authority can comprehensively execute its duties.

Among those responsibilities is a new one to take into account and report 30-year projected ridership, number of affordable housing units within a 15-minute walking radius of stations, and the number of transit-dependent households in the area. These numbers would be taken in the context of financing and systems plans, so that a CTA would have to plan with long-term ridership, and equity in mind. This could mean expedited additions of future services and future-proofed infrastructure to expand light rail to places like Renton, South Park, Georgetown, Kenmore, Burien, Edmonds, and the Aurora corridor in order to serve our region equitably and add them without disruption to the system.

Beyond adding funding, the ability to plan ahead will also stretch existing funding further, avoiding expensive late-in-the-game property acquisitions or major alterations to add junctions in light rail lines already in service.

“Imagine trying to tap into an underground tunnel when it wasn’t built to accommodate that in the future,” Hopkins said. “It’s going to require shutting down the system for a year, and it’s going to cost hundreds of millions of unnecessary dollars. So originally this bill was devised as a way to get ahead of that process and fix our planning process. So we build with the future in mind.”

The status quo isn’t serving the region well. “Every time we build something, we build it like it’s the last thing we’re ever going to do,” Hopkins said. “And that’s no way to run a railroad.”

Other Provisions

Section 9, which discusses post-completion and dissolution of the authority, has been nearly entirely rewritten. Previously, a petition could propose dissolution of monorail authorities through a process that ended up with a vote in 2007–an amendment in 2007 created for the 2008 dissolution of the Seattle Monorail Authority, whose economic woes led to a 2005 final vote that ended the Seattle Monorail Project. The bill would change this to allow dissolution of an authority once its work is done, debt is paid, and upkeep and operation transferred to another body. Alternatively, the authority could downsize to just carry out upkeep requirements like operation and maintenance.

Other sections that the bill would add to Chapter 35.95A RCW create systems for a city transportation authority to be more equitable. Section 11 would allow for a rebate program to refund low-income individuals up to 40% of special excise tax or vehicle license fee imposed by the authority. Section 12 goes much further, requiring an authority to create a system plan for implementing equitable transit-oriented development. This section dictates that at least 80% of disposed or transferred surplus property (such as staging areas used during transit construction no longer needed afterwards) must be offered at no cost, sale, or longer-term lease first to local government, housing authority, or nonprofit developer to develop affordable housing. This can be waived if it would be in conflict with a federal grant program eligibility, or if a transfer is done to facilitate permitting, construction, or mitigation of grade-separated transportation facilities and services.

Some equity measures were already built into the chapter, such as requiring signage that is accessible for persons with disabilities, non-English-speaking persons, and visitors. Another new section requires a city transportation authority to receive state funding to submit a maintenance and preservation management plant for certification by the Washington State Department of Transportation.

Next Steps

This bill is still fresh. Let your state representatives know if you support the bill and what amendments you’d like to see to it. If you live in a mid-sized Washington city and you would like to have the power to establish a local city transportation authority, let your representatives know you want the population limit reduced.

House Bill 1304 offers our cities more power to pursue emission-free transportation options, improve the quality of our urban built environment, and lessen our carbon footprint and environmental impact.

Doug Trumm contributed to this reporting.

Update: This article has been updated with the Hackney quote, the estimate of total revenue, the timeline graphic, and a caveat about limited use of gondolas for station access being possible under bill language.

Shaun Kuo is a junior editor at The Urbanist and a recent graduate from the UW Tacoma Master of Arts in Community Planning. He is a urban planner at the Puget Sound Regional Council and a Seattle native that has lived in Wallingford, Northgate, and Lake Forest Park. He enjoys exploring the city by bus and foot.