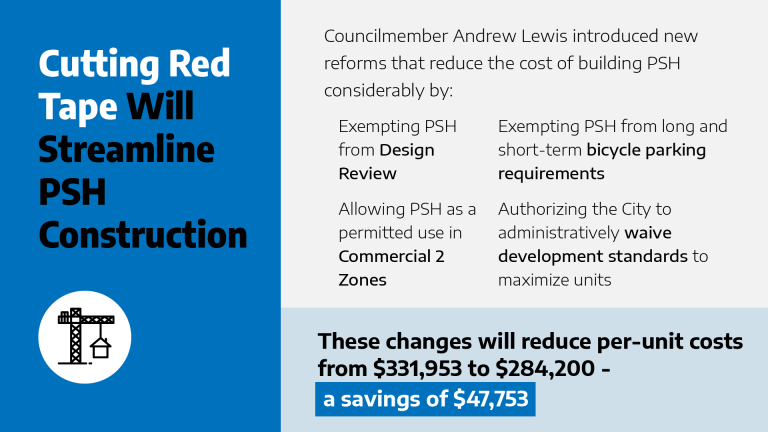

In December, Councilmember Andrew Lewis introduced legislation that could make it cheaper, easier, and faster to build permanent supportive housing (PSH) in the City of Seattle. If all goes according to plan, PSH providers could trim about 15% from building costs.

Permanent supportive housing helps combat the homelessness crisis with an affordable, communal, and service-connected environment for unhoused people. Providers like Plymouth Housing tailor their residents’ needs with a service combination of medical, behavioral, and substance treatment, hospice care, veterans counseling, family reunification, money management programs, and community activities. PSH comes in the form of multifamily residential buildings that may have their services on-site.

Currently in Seattle, PSH developers have to undergo many of the same processes and regulations that other multifamily housing developers follow. The requirements limit PSH developers’ ability to provide the housing our city and chronically homeless critically need. Lewis worked with PSH providers and city staff to craft the legislation and is hoping to change that reality.

Pinning down what PSH is

On December 15th, the Council’s Select Committee of Homelessness, City staff, and PSH providers met to discuss the bill. First topic up was the definition of PSH in the bill, and needed coordination with the Office of Housing to align PSH qualifications, as the department’s funding is omnipresent in PSH projects in the city. PSH was added to Washington’s Growth Management Act (GMA) two years ago, defining it as:

[S]ubsidized, leased housing with no limit on length of stay that prioritizes people who need comprehensive support services to retain tenancy and utilizes admissions practices designed to use lower barriers to entry than would be typical for other subsidized or unsubsidized rental housing, especially related to rental history, criminal history, and personal behaviors. Permanent supportive housing is paired with on-site or off-site voluntary services designed to support a person living with a complex and disabling behavioral health or physical health condition who was experiencing homelessness or was at imminent risk of homelessness prior to moving into housing to retain their housing and be a successful tenant in a housing arrangement, improve the resident’s health status, and connect the resident of the housing with community-based health care, treatment, or employment services

This addition made it illegal to ban PSH in multifamily and mixed-use zones. Today, the City doesn’t have specific regulations that govern PSH development. Lewis’ proposal would refine the GMA definition down to PSH as a multifamily residential use that has at least 90% of units affordable to very low-income households (a memo pins that down to under 50% of area median income or AMI), receives public funding or an allocation of federal low-income housing tax credits, and has a contractual term of affordability of at least 40 years.

The Council discussed amending the AMI figure in the definition to include a mix of 30% of AMI households and 50% AMI households. Lewis (who chairs the Select Committee on Homelessness) had wanted it to be 90% for 30% of AMI households, but the Office of Housing thinks more diversity for the figure will help developers attract low-income tax credit investors, and government aid.

Discussion of the bill

On top of setting the definition, the bill would:

- Establish on-site supportive services as an accessory use to PSH and exempt floor area for services from floor area ratio requirements;

- Exempt PSH from design review and long and short-term bicycle parking requirements;

- Authorize the Director of the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections to waive or modify specified development standards;

- Require developers of supportive housing to submit a community relations plan; and

- Allow PSH as permitted use in Commercial 2 zones and as a street-level use in zones where street-level uses are required.

Discussed in great detail during the meeting was the desire to relieve PSH providers from the bike parking minimums that are required for new multifamily development. Representatives from Plymouth Housing and Chief Seattle Club pointed out the demographic served leans older and disabled, lowering the need for bicycle parking per person in supportive housing. They also discussed the preference for residents who do have bikes to keep them in their homes because they may count them as some of their most very valuable possessions–equating those bikes to the value of a car to a car owner. Probably the most important arguments included the steep $300,000 to $500,000 cost per bike room, space, and funding that could be used for amenities or more housing, and the fact that it would be occupying the more expensive part of a building. Writing in Seattle Bike Blog, Ryan Packer backed the idea of dropping the requirement for PSH.

The representative from Plymouth Housing also estimated that relief from design review would speed up the permitting schedule by four to six months, a figure that the City staff couldn’t produce at the time. City staff did say that they could produce a figure on time savings because during the pandemic design review was waived for affordable housing projects, allowing staff to compare pandemic-era and pre-pandemic affordable housing project schedules. The exemption could also save PSH developers the roughly $200,000 to $300,000 cost of putting together a design review packet.

Councilmember Tammy Morales expressed concerns about a PSH provider being able to waive potentially beneficial amenities. City staff, however, indicated that competition over funding would check hypothetical developer desire to not include a beneficial service for economic benefit. Councilmember Alex Pedersen decided to explore the greedy developer narrative further by discussing a scenario where a developer uses PSH design review exemptions and then decides to pivot out of PSH later. City staff pushed back on the concern with the regulatory agreement attached to City funding. All PSH projects in recent memory have City funding, so they have to meet city funding requirements. They also pointed out the difficulty of going through the whole PSH process, and litigation if a developer did betray funding requirements.

Possibility of funding from the County, rather than the City, was brought up with the recent passage of the county sales tax for affordable housing. If the County or another public source had weaker funding requirements, Pederson speculated that the legislation could be exploited. City staff responded with the need for further discussion with the Office of Housing to see what kind of amendments might be made to lock in PSH projects. Pederson also asked about an internet requirement for PSHs with City staff noting the appropriate place for that kind of regulation would be in housing funding policies and not land use regulations.

Next steps

Based on a May report by the Third Door Coalition, getting to 6,500 units of permanent supportive housing–an estimated $1.6 billion dollars of PSH investment–within five years would be needed to meet the demands of the Seattle and King County’s shelter crisis. The coalition of business leaders and homeless rights advocates outlined building 4,500 new units, and securing and leasing 1,000 more units in scattered sites. They believe that PSH is the best solution for neighbors experiencing chronic homelessness, and that Lewis’ proposal could save providers just under $48,000 per unit.

Councilmember Lewis hopes to get more vetting of the legislation done and perhaps a full vote on the bill this month, or at least in the first quarter of 2021. Contact your councilmembers to back the bill if you support making supportive housing development easier and less expensive.

Shaun Kuo is a junior editor at The Urbanist and a recent graduate from the UW Tacoma Master of Arts in Community Planning. He is a urban planner at the Puget Sound Regional Council and a Seattle native that has lived in Wallingford, Northgate, and Lake Forest Park. He enjoys exploring the city by bus and foot.