Yesterday, Puget Sound Business Journal published a story on Bellevue’s affordability efforts. Despite some optimistic quotes from local leaders, Bellevue has yet to crack the code or doing anything of note, as far as I can tell. Notwithstanding bluster about outdoing Seattle, Bellevue suffers from the same problems, and arguably is worse off and doing less about it.

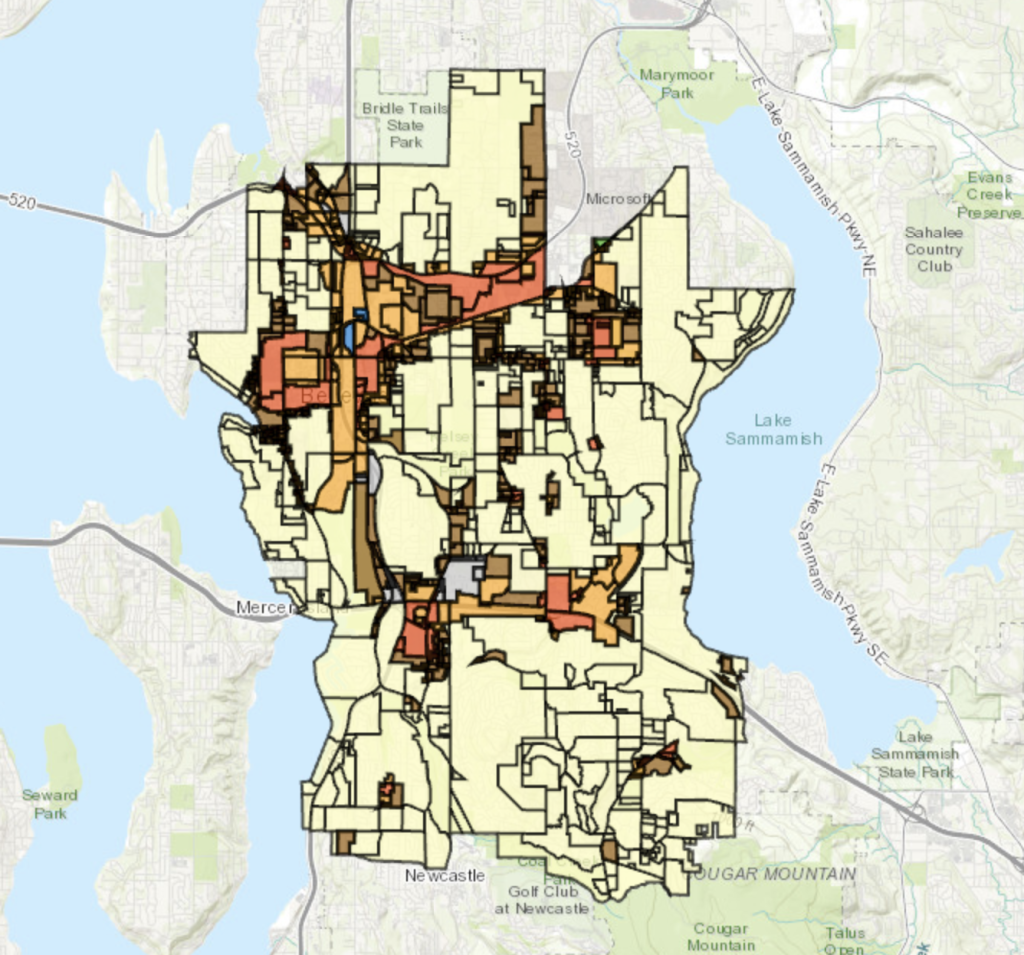

Approximately 75% of Bellevue is zoned for detached-single family homes. Backyard cottages are illegal in those zones and the rules around attached accessory dwelling units (ADU) are restrictive, and unlike Seattle and several other Puget Sound cities, it hasn’t passed reform liberalizing ADU rules.

Four-term Bellevue City Councilmember Jennifer Robertson has even argued changing single-family zoning is impossible because of Bellevue’s “heavy clay soil” and the need for expensive sewer upgrades, which Bellevue, despite being one of the richest cities on earth, apparently can’t afford.

Robertson remains popular. She most recently defeated civil rights attorney James Bible, former head of the King County chapter of the NAACP, garnering more than 60% of the citywide vote. Bible argued the city was too beholden to Amazon, ill-prepared for the influx of office workers, and needed to boost funding for social housing.

Bellevue has followed in Seattle’s footsteps in funneling the bulk of its growth to its downtown core. Tony Lystra’s reporting suggests Bellevue Mayor Lynne Robinson still is hoping that can work: “None of those policies touches single-family homes, Robinson said. Still, she said, with 30% of downtown yet to be built out, there’s a chance for Bellevue to make condos and apartments affordable for those with more modest paychecks.”

Zillow pegs the median home value in Bellevue at $1,056,000, while RentCafe estimates the median rent in Bellevue at $2,188–$200 higher than Seattle’s current median. It’s also on a starling trajectory. “The city saw a 33% jump in its rental prices between 2019 and 2020, according to the Bellevue Chamber of Commerce, one of the steepest increases in the nation among similar-sized cities and larger,” Lystra noted.

This is a city with an affordability crisis arguably worse than Seattle’s, caught flatfooted about it, but still acting superior and on top of things.

Bellevue badly needs to tackle its restrictive zoning and land use policies, like nearly every city in the region. But unlike many other suburbs, Bellevue is a hotbed of high-end office growth to serve the various tech giants. Amazon has made a splash pledging it will bring 25,000 jobs to the city in the next four years, while hinting it will spurn Seattle due to frustration with its failure to buy the Seattle City Council and thus prevent the City from taxing it. In 2020, the Seattle City Council passed a progressive payroll tax (which hit Amazon most of all) as part of the JumpStart Seattle plan aimed at Covid relief and funding social housing.

Likewise, Kirkland is focusing its rezone efforts on promoting office growth rather than housing growth. It’s NE 85th Street plan calls for nearly four times as much office space as housing, with a 10-acre site near its NE 85th Street bus rapid transit station set to become a major expansion of Google’s Kirkland campus. Kirkland, at least, liberalized its ADU rules to allow two per lot.

Eastside leaders seem to relish the opportunity to siphon corporate jobs from Seattle, but they haven’t grappled with the consequences to their local housing crises. While they tout housing investment efforts from Microsoft and more recently Amazon, municipal leaders have yet to provide the broad upzones those corporations say are needed to support their job growth with housing growth.

In 2019, Redmond-based Microsoft made a $500 million affordable housing commitment to the Puget Sound Region–mostly in the form of low-interest loans, though some grants were included too, and it added another $250 million in 2020. Last week, Amazon made a $2 billion pledge–again mostly low-interest “below-market” loans to affordable housing providers–across its three headquarter regions, meaning Puget Sound would share the bounty with Northern Virginia and Nashville.

The company says its initial investment in the Puget Sound Region will be $161.5 million in loans and $24 million in grants. The grants will be used to preserve 1,000 homes in King County at rents below 80% area median income–470 of which have already been acquired in Bellevue. Amazon is partnering with the King County Housing Authority on the investments, which does not operate in Seattle city limits. The omission could carry with it a message to Seattle’s leaders for passing the JumpStart tax.

Amazon and Microsoft have admitted their sizable investments are not enough to solve the housing crisis and encouraged officials to take more actions to promote affordability. Since Amazon’s strategy is to preserve rather than build new homes, it’s also primarily mitigation rather than directly ramping up housing production.

Like the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, Amazon says it supports zoning reform, but hasn’t flexed its political muscle to get it–even with Bellevue portraying itself as the city that will partner with companies rather than antagonize them with taxes and rhetoric.

Republican-leaning Bellevue City Councilmember Jared Nieuwenhuis boasted of the fact while conversing with conservative radio host Jason Rantz: “Quick, side story: Myself and a couple of colleagues–like Councilmember Jennifer Robertson–met a couple of folks from Amazon at a business dinner recently, and we actually went up to them and said, ‘We’re glad that you’re in Bellevue, welcome. Let us know if there’s anything we can do for you.’ And they looked us like we were from Mars.”

Apparently, Amazon’s direct entreaties haven’t included broad zoning changes–or those councilmembers were exaggerating their cooperativeness.

Amazon lobbyist Guy Palumbo is a former state senator who pushed a “minimum density” bill preempting local zoning in order to promote density near transit back in 2018. Palumbo failed to get his ambitious bill passed. At Amazon’s lobbying shop, he’s continued to make the case–though he and Amazon have also backed conservative candidates that oppose zoning changes, like Seattle City Councilmember Alex Pedersen. Amazon also gave $2,000 to Jennifer “clay soil” Robertson in 2019, according to Public Disclosure Commission filings.

“It’s up to cities and counties to change zoning laws that are creating scarcity,” Palumbo said in a recent tweet. “If they can’t, then the state needs to. It shouldn’t be illegal to build a duplex in a majority of the state’s largest city. #housingequity”

A city of 148,000 just across Lake Washington from Seattle, Bellevue will be the beneficiary of East Link light rail expansion in 2023. The city is looking to promote growth near its light rail stations, particularly East Main, Downtown, Wilburton, Spring District, and Bel-Red. Downtown Bellevue already got a rezone, and East Main and Wilburton rezones are in the works. Like the Spring District master plan, these plans tend to emphasize office over housing growth, though Sound Transit’s transit-oriented development site is a welcome exception. So far citywide changes don’t even appear to be on the radar, despite efforts by advocates like Christopher Randels to start a conversation about zoning and transforming to a 15-minute city.

With Amazon’s next 25,000 jobs in the region apparently headed to Bellevue, it’s crucial the city get it right. Their zoning is much more restrictive than Seattle’s, with higher parking requirements and backyard cottages banned. Amazon appears to have leverage to push for changes, but instead of using it they’ve supported candidates who oppose changing zoning outside of a few narrow areas. Instead of being a visionary city of the future, Bellevue may end up known as Clay City–famous for being stuck in the mud and providing excuses why it can’t change or end its apartment bans.

Update: I added a sentence noting Kirkland’s ADU reform.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.