The car is an amazing machine. So amazing, that with a little help from cheap portable fuel and a flood of public investment in smooth, wide, and straight (ish) roads (thanks Ike), our car dependent form of living has come to dominate a whole continent. This dominance is so complete, that from behind a steering wheel it is difficult to see the system as anything less than necessary, much less imagine a different path forward or consider the true cost of our continued allegiance.

After tackling Five road widening myths that are delaying climate action, let’s look a little deeper at how cars shape the geometry that we find ourselves living in–and what that tells us about the far reaching consequences of the infrastructure decisions (e.g., bridges, freeways, land use, and zoning) we will face in the very near future.

The car chronicles of time and space

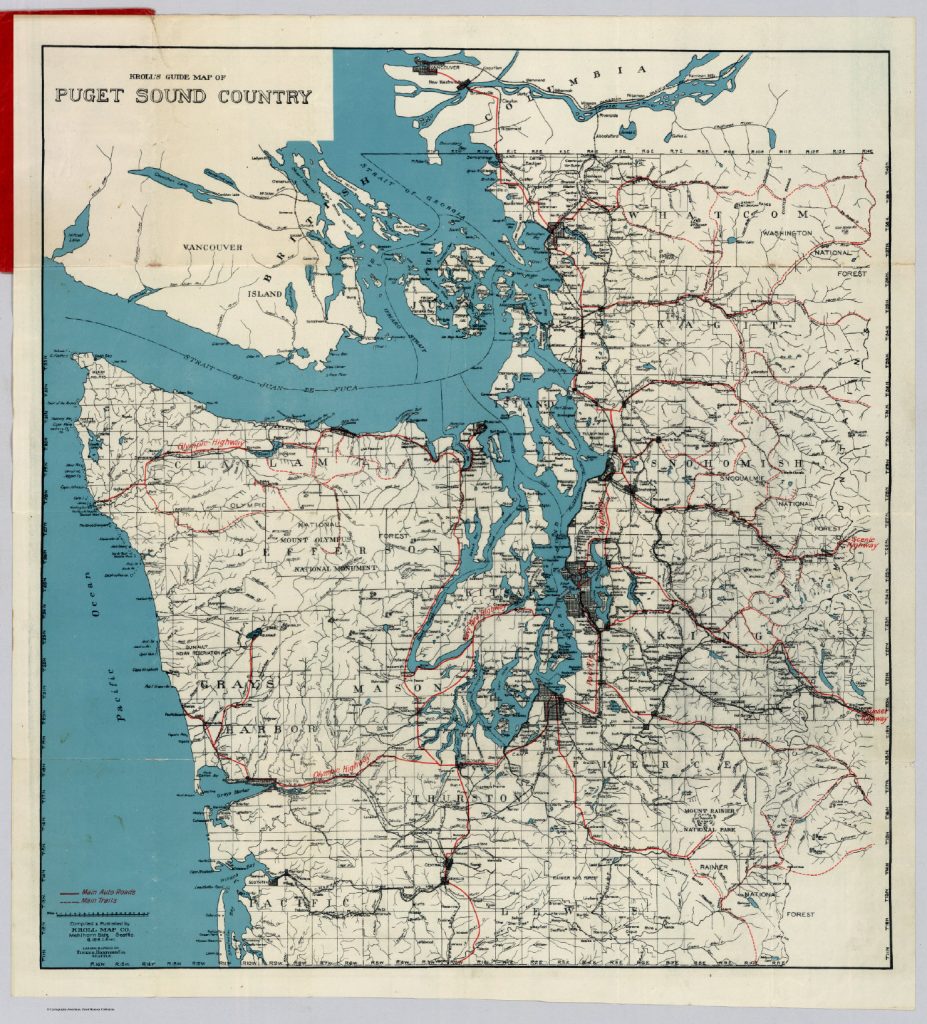

Part of the goal of this piece is to think through the rippling consequences of decisions made locally (widen a road, build a flyover to make an intersection free flowing) on the geometry of how we live in the region. Over the past 50 to 100 years, many of these decisions have focused on how to move more cars and how to move them faster. Setting aside profit motives, lobbying, and devious gambits of the automobile and fossil fuel industries—the faster a person can travel from where they live to where they are going, the more land there is available for folks to live on.

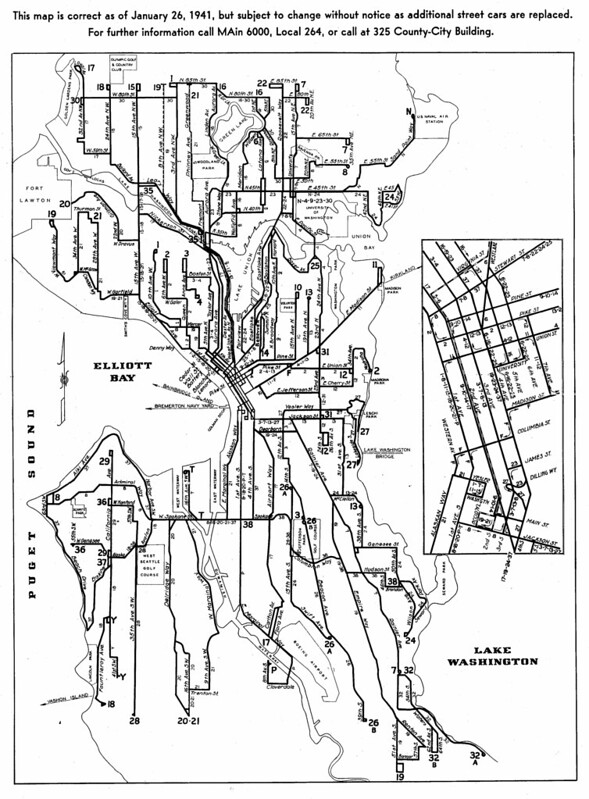

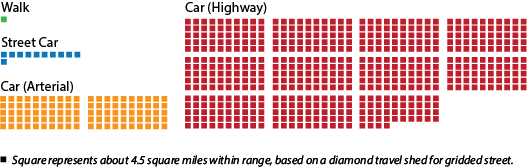

For example, before cars, where people lived was primarily constrained by how fast they could walk to where they are going. At an average walking pace of three miles per hour, this puts anything within 1.5 miles a reasonable 30-minute travel time away. Not coincidentally, the old core of Paris is about a 30-minute walk across. A decent streetcar system can up travel speed to 10 miles per hour, opening up five-mile trips to 30-minute commutes. As more and more people lived in cities, technology like the streetcar opened up more land for people to live on and the imprint of that mode of transportation, even though the tracks are long gone, is apparent in most American cities.

Enter the automobile. Whether we are talking about the humble Model T (top speed 45 mph, 20 horse power) of 1908 or the souped-up dragster Honda Civic (top speed 119 mph, 150 hp) of 2020, cars are fast. Off the shelf (and ignoring traffic and safety), no other technology can take you from A to B (rather than station to station) as fast as a car. Cars are so fast that top speed really doesn’t mean anything, instead we will (optimistically assuming no stops or traffic) use standard speed limits–30 mph for in the city, and 70 mph on the freeway–for the purposes of this journey.

At 30 mph we can now go 15 miles (about tip to tail of Seattle!) in our reasonable baseline of 30 minutes, and if it is on-ramp to on-ramp (so many optimistic assumptions!), a whopping 35 miles on the freeway. For those keeping track at home, the automobile (and freeway system) opened up a lot of land for people to live within commuting distance.

Speed has its consequences

The evidence of the transition to this car car world is written across most North American cities in the transition of a tight regular walkable street grids (black grids on the map below) and streetcar suburbs, to arterials and freeways (outlined in red on the map below) feeding cul-de-sacs and quarter acre ranchettes.

Leaving out why this happened (covered here, and here, among other places with more appropriate detail), high-speed car travel was the technology that made it possible. And now, like peanut butter and jelly, the cul-de-sacs and far flung suburban homes justify the subversion of all other goals to that of moving more cars and moving them faster.

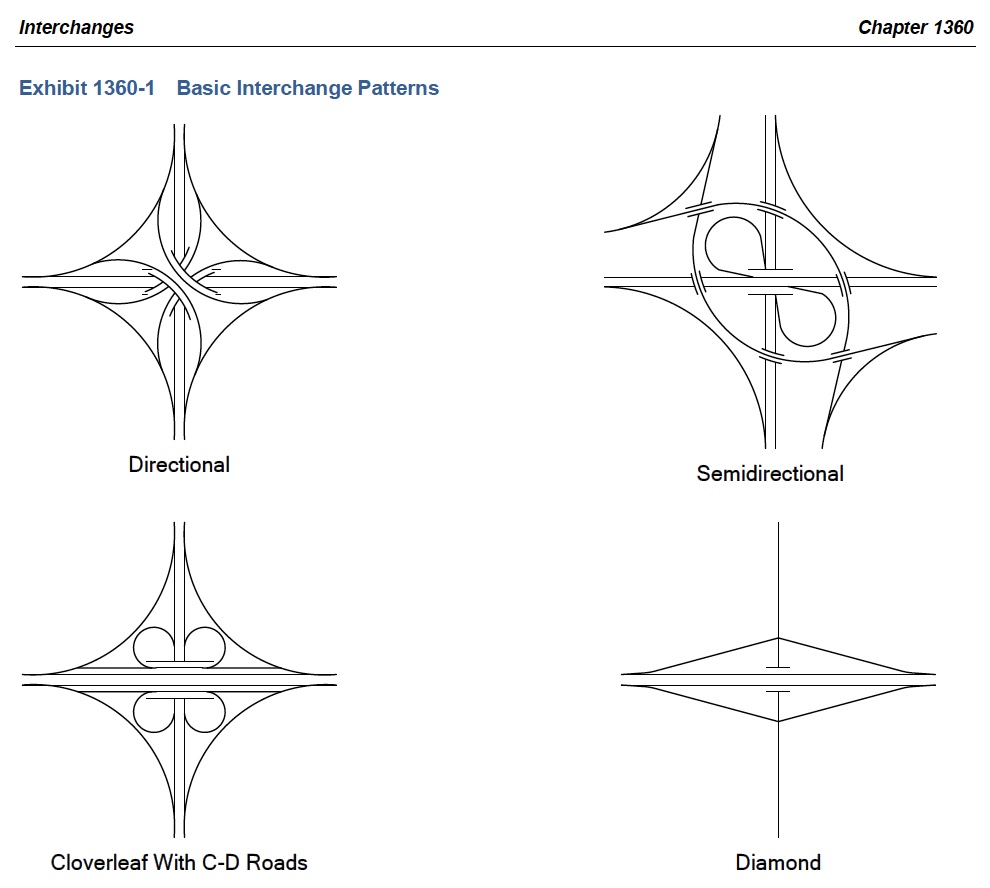

Freeway interchanges that consume whole neighborhoods and valuable urban land? Necessary1 for the wide turns required by the physics of friction if you’re going to keep going fast and change direction (also see acceleration/deceleration for on-ramps/off-ramps).

“Slip lane” at an arterial intersection to avoid waiting behind cars going straight? Have to have it. We can only assume that the road designer is tasked with avoiding the delay and back up if all those cars were piling up behind one another–not the now constant flow of vehicles at deadly speed where some poor soul might want to try and cross the road. This is a car car world after all, we’ll put in a flashing beacon and roadside memorials for the dead as necessary. In fairness, the slip lane—as the low hanging fruit of the road safety world—have started to be reclaimed for people…though they also pop back up even in safety focused updates. Let’s keep that speed up everyone.

A failed transportation system driven through the heart of a broken land use system

Over and over again, we carve out more space for speed and sacrifice goals of safety, health, livability, and the environment. All this effort, money, land, and life, but the system is still failing. The number of people commuting more than 90 minutes each way (61,000 pre-Covid!) and the number of people missing out on time with family and friends is climbing. Too many people live at the end of the freeway, or along that high-speed arterial. The roads fill up faster than they can be widened or plowed through the next ‘unlucky’ neighborhoods. Faster and faster the places people are going are bulldozed to make room for the way people are getting there.

A Brief Digression for the Climate Consequences

Now, on the edge of cities and metropolitan areas, we carve disconnected neighborhoods out of forests and farmlands. If the shredding of community and the environment is not bad enough, this also has consequences for the carbon emissions causing climate change. Every year carbon dioxide is emitted as those speeding cars take people home to the newly accessible land–but carbon is also lost in clearing that land. If you will forgive one last exploratory mathematical digression (details and caveats below2), the average person living in King County drives about 8,000 miles a year, leading to carbon emissions of about 0.84 tons carbon per year (considering an average fuel efficiency).

In addition to these direct emissions, Pacific Northwest forests are a tremendous store of carbon, both pulling it from the atmosphere throughout the year and storing it in their trunks, branches, and roots. Estimates show that forests here can remove 0.56 tons of carbon from the atmosphere per year per acre to store in their biomass. So, if this average person’s house sits on a quarter acre suburban lot, clearing that forest not only removed all the stored carbon already there–that suburban lot worth of 200-year old forest (young!) is holding about 33 years of our average person driving–but also quenched the 0.14 tons of carbon per year captured from the atmosphere. That annual carbon uptake is similar to if you were adding another 1,300 miles of driving per year.

Time for speed to take a backseat

We built a car car world to get us there fast, we sacrificed neighborhoods, lives, our health, and our wealth but the promise of speed has not been realized. The automobile is an amazing machine, but a transportation system built around it–even in the narrow goal of going A to B–no longer serves us. We can continue making decisions intersection by intersection to relieve some congestion, only for it to appear a little way down the road at the next bottleneck, or we can start thinking about each intersection in context of the whole system, opening up room for goals like justice, happiness, and health. We can start allowing people to live closer to where they need to go, allow them to slow down, and make more places to be, rather than just places to pass through. Maybe even get to know our neighbors once the busy car streets are calmed.

Fixing this isn’t going to be easy, but we can start by considering the true costs of the car car world and then completely abandoning the mantra of ‘more cars faster’. Instead, let’s make each decision about a system that works for people–not to mention salmon, forests, climate change, entire ecosystems, and the future of the planet. Those decisions, while seemingly small and disconnected add up–whether it is how tall our buildings are allowed to be and who can live in them, closing one slip lane, or rebuilding I-5. Optimistically there may even be some help from the incoming Biden administration where $10 billion is being considered for highway removal. There is no time to waste.

1The Washington State Department of Transportation actually suggests twice the frequency of interchange spacing in urban areas (every one mile) versus rural areas (every two miles), chewing up even more land where people live more densely.

2A few more details on the carbon stored in Pacific Northwest Forests. We are using estimated carbon stored per area numbers from here and here that are based on the wet side of the mountains forests. The range can be large and forests grow at different rates throughout their lives. It is also quite likely that the person living on a quarter-acre lot in the King County suburbs drives more than average, as the average includes folks that walk to work from the apartments downtown. Carbon emissions per year from driving: average vehicle miles traveled per capita (8,000 miles per year per person in King County 2019) divided by average fuel efficiency (25.1 miles per gallon, US) multiplied by 2,400 grams of carbon in a gallon of gas. For carbon removal from the atmosphere per year by forests: carbon per area (250 megagrams of carbon per hectare after 200 years) divided by 200 years multiplied by quarter-acre lot (0.10 hectares). Finally, this is strictly looking at carbon, but forests provide many benefits beyond just their carbon capture and storage.

Author’s note: Updated figure of square miles to reflect a transportation shed diamond of 4.5 miles square and clarify calculation.

Gregory Quetin

Gregory Quetin is a climate scientist and aerospace engineer with a PhD and bachelor's degree from the University of Washington. He advocates for a city full of housing, commerce, industry, and recreation as ways to increase resilience to climate change and reduce carbon emissions.