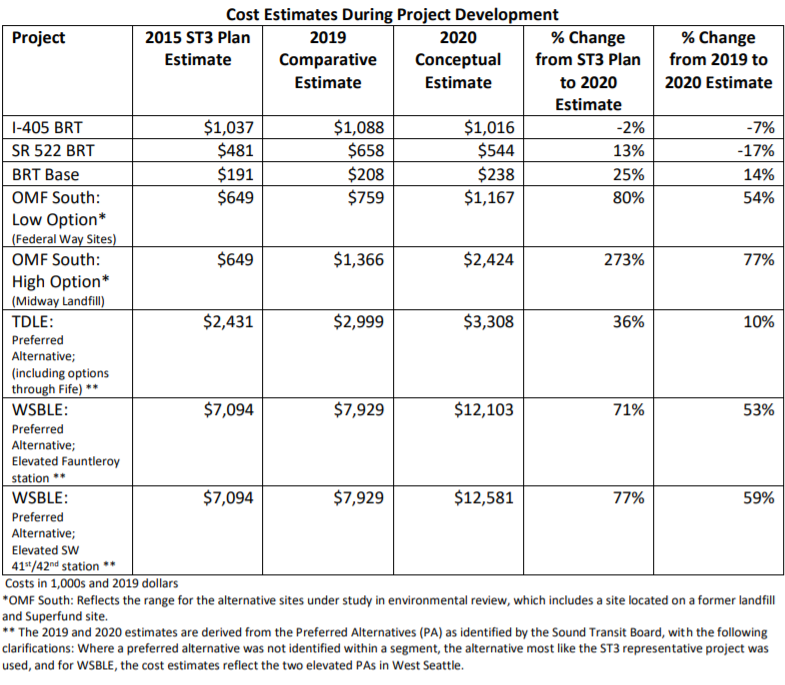

Sound Transit is projecting an additional $4 billion in costs for light rail to Ballard and West Seattle. The projected cost of the two lines jumped from $7.9 billion in 2019 to $12.1 billion–a jump exceeding 50%. The agency revealed the bad news at the Sound Transit Board meeting yesterday and blamed skyrocketing costs for land acquisition, labor, and construction materials. In fact, property costs alone jumped $2.13 billion–a 263% increase.

While the Ballard and West Seattle light rail extension numbers were the most dramatic, all Sound Transit 3 light rail lines are seeing cost escalations. The Tacoma Dome Link Extension costs have climbed from $2.4 billion in 2015 to $3.3 billion as of the update yesterday. The culprit there is the agency’s determination that an extra three miles of elevated rather than at-grade rail will be needed due to concerns about drainage and disrupting indigenous burial sites as the route passes through the Puyallup Reservation.

The presentation didn’t detail Everett Link or Issaquah Link cost projections, but noted they had taken a hit as well. On a positive note, Sound Transit 2 remains on track with 62 miles of light rail expected to be open by 2024, with Lynnwood Link and Federal Way Link opening then and East Link a year earlier in 2023. Northgate Link will open later this year, and revolutionize transit in North Seattle, even if King County Metro’s bus restructure fell victim to budget cuts.

Sound Transit CEO Peter Rogoff tried to assure the board. “While these numbers are sobering, they’re not catastrophic,” he said, suggesting the plan could be fine-tuned and scope adjusted to control costs.

Deputy CEO Kimberly Farley cited transit project examples from San Francisco, San José, and Los Angeles to show rapidly escalating construction costs are an issue regionwide. In a official memo, Farley described how Sound Transit arrived at the new estimates and laid out next steps.

“Given this cost growth, I have initiated an independent assessment of Sound Transit’s updated cost estimates and underlying methodologies,” Farley said. “It will include a focus on what actions Sound Transit can take to reduce costs and update its estimating approaches going forward. The independent assessment will be completed in sufficient time to inform the upcoming capital program realignment process.”

Over-engineering is partially to blame

Some of Sound Transit’s cost escalation is unavoidable; the agency can’t control how much building materials cost or construction contractors charge. They can’t prevent Trump from starting a trade war and increasing the cost of steel with his tariffs. Nonetheless, a portion of the spiking costs seems to be attributable to Sound Transit over-engineering stations and guideway to require greater, more expensive property acquisition than is really necessary.

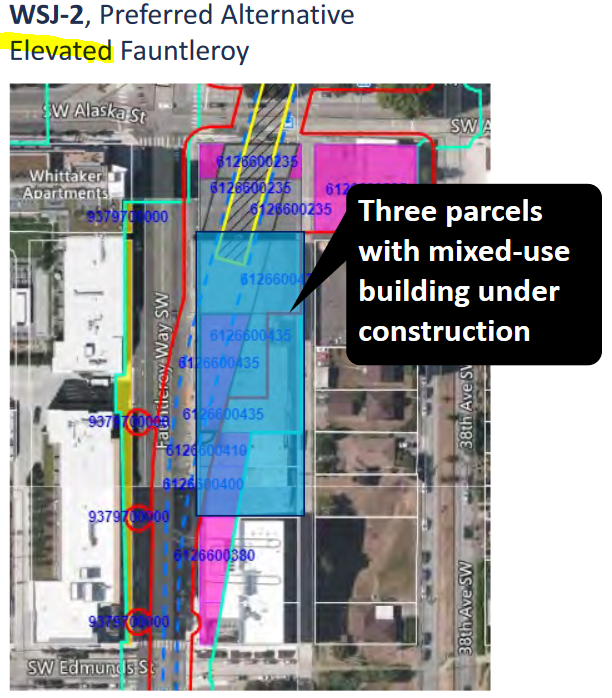

The presentation’s prime example with West Seattle Link illustrates the point. The agency says they expect they’ll need to acquire three brand new apartment buildings on Fauntleroy Way to site the station and track for the Alaska Junction Station. Doing so is projected to cost approximately $250 million and require relocating 306 households, the agency said.

However, better contouring the alignment to Fauntleroy Way SW would likely avoid demolishing these new apartments and save upwards $250 million. Fitting the guideway and station into the Fauntleroy right-of-way and the lower-value properties to the north–a Shell gas station and Les Schwab tire center–appears doable. Since it’s near a station, trains would not be moving quickly at this point.

A station needs to have straight track, so, if this can’t be arranged at the SW Alaska St intersection, a simple fix would be to site just to the south or north along (or straddling) Fauntleroy Way, avoiding the kink. Fauntleroy Way right-of-way is 90 feet wide north of Alaska Street and 80 feet south of it. It’s a wide street that can accommodate elevated rail in its envelope and a station too–though Sound Transit will need to acquire property for staging regardless.

The Urbanist has reached out to Sound Transit to inquire why the agency isn’t avoiding these three costly properties by tightening the turn. Sound Transit spokesperson Geoff Patrick did offer a general statement, but a full response is still pending.

“The Board has selected preferred alternatives for much of the alignment, other alternatives are also being studied as part of the current work to publish a Draft Environmental Impact Statement,” Patrick said in an email. “And the Board won’t select the final alternative to be built until after publishing a Final Environmental Impact Statement. Those three parcels are in play because of the specific alternative that intersects with that location.”

“We always try to minimize impacts to property,” public information officer Rachelle Cunningham added.

While $250 million is only 6% of the $4 billion cost escalation, if this is a pattern and other stations and guideway have been over-engineered to require expensive property acquisition, then it could add up. Like Alaska Junction, Ballard is booming and the station area imagined near 14th Avenue NW and NW Market Street has seen large buildings go in too, as has Interbay near W Dravus Street. It’s a good problem to have to know that light rail will serve a dense and growing neighborhood, but it does make property acquisition more expensive and fraught.

Property costs and construction costs have continued to spike in Seattle right through the recession, so it’s hard to imagine a respite any time soon. Prime properties won’t be getting any cheaper, as King County Executive Dow Constantine argued, saying we must forge ahead.

Fodder for opponents of elevated light rail

Some West Seattleites’ dream of tunneling the light rail line to reduce the “eyesore” and noise. Others are pushing to replace rail with a gondola to lower costs and add whimsy. Elevated rail remains the more expandable and best fit, especially if the land acquisition pickle can be solved. That said, obviously $4 billion in added costs will bolster the case for alternatives, as the West Seattle SkyLink group was quick to note.

Sound Transit’s estimated that a tunnel alignment would add at least $700 million in costs and require third-party funding. (An additional $200 million Pigeon Point tunnel has already been eliminated.) The cost differential between elevated and tunnel alignment may have gotten smaller with this news from Sound Transit, but a tunnel is likely still much pricier–and would continue to be as light rail ultimately extends south toward Burien and points between.

A gondola, on the other hand, while cheaper doesn’t offer sufficient capacity or expandability to meet West Seattle’s needs long-term. Sound Transit projects West Seattle Link will get 35,000 daily riders when it opens–ostensibly in 2031. One of the busiest gondola line in the world appears to be the Line K in Medellín, Colombia with upwards of 30,000 daily riders. Gondolas come more often but are also much smaller than a traincar, which means queuing lines still develop, especially at peak times. Apparently the line to catch a K in mountainous barrio of Santo Domingo Savio can stretch to 45 minutes at peak, but the locals are content to wait since the alternative before the gondola was buses that took two and a half hours to switchback down the mountain. It’s hard to imagine a West Seattleite waiting 45 minutes for a gondola.

Political considerations

The Sound Transit Board has some tough decisions to make. The added costs would mean slower timelines unless revenue picks up or is added. Likely, some suburban legislators will renew their harangues against Seattle light rail lines they see as expensive and less essential than the “spine” from Everett to Tacoma.

Mayor Jenny Durkan complained about transparency, but she raised a good point that boardmembers should be flexible in siting stations to avoid particularly costly locations to buy land.

“Some of this information obviously was available at a time when we should have had it while we were deciding and approving increased costs for projects over the last year,” Durkan said.

Some cost cutters may also press the case for bus rapid transit (BRT) instead of light rail. The bright spot of the cost update news, is both BRT projects are under budget. For SR-522 BRT, the primary reason for being 17% under budget is jettisoning the Woodinville section of the line and cutting back other elements of project scope.

For I-405 BRT, piggybacking on some Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) highway widening projects helped save Sound Transit some money. However, the drawback is that station like Kirkland’s NE 85th Street Station are nestled with 18 lanes of traffic at a busy interchange–not terribly conducive to growing a neighborhood around the station let alone providing a pleasant place for riders to wait and transfer or walk to their destination.

Part of the challenge for transit planners is to put stations where people want to live. People don’t want to live right next to a freeway if they have a choice, and there’s ample evidence doing so is bad for human health, with road pollution linked to elevated rates of asthma, for example. Bus rapid transit is relatively cheap when operating within existing highway right-of-way, but it can’t solve that problem when doing so.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.