Seattle’s boundaries are ridiculous. In the north, the city is separated from its neighbors by the width of a street. In the south, the errant wiggles and tight bends of the boundary work to cut neighbor from neighbor while scooping up shreds of parkland.

Politically, the city lines are exactly wrong. For some issues–building transit, responding to climate change and homelessness–the city’s tax pool and effectiveness are not expansive enough to make significant change. For other issues–getting sidewalks built, responsive public education, police accountability–the bureaucracy and the space the city covers are just too sprawling.

The way we cut up our land segregates communities, divides neighborhoods, and ignores the harsh truth: city and county political boundaries are worthless in tackling modern problems. At best they are convenient excuses to exclude. At worst, they create the cracks through which people and neighborhoods fall.

Entrenching the boundaries further, making the walls bigger and the moats wider by pulling Seattle out of King County and establishing it as a county, is the last thing that’s needed right now. Seattle should not be its own county.

Lessons from elsewhere

The first thing to remember about counties is that it’s old language. In European tradition, you have ranking members of the imperial military who were given ownership and administrative responsibility to some portion of the emperor’s domain. That person was a count, like Dracula or Monte Cristo, and their territory was a county.

The 11th century Normans transferred the idea to England, who got county wrapped up with their territorial name, a shire. That’s why the wife of a British Earl is a Countess and the administrator of a county is a shire-reeve or sheriff. Long story short, Robin Hood got in trouble with the Sheriff of Nottingham for thievery in Sherwood Forest because it was in the administrative county of Nottinghamshire.

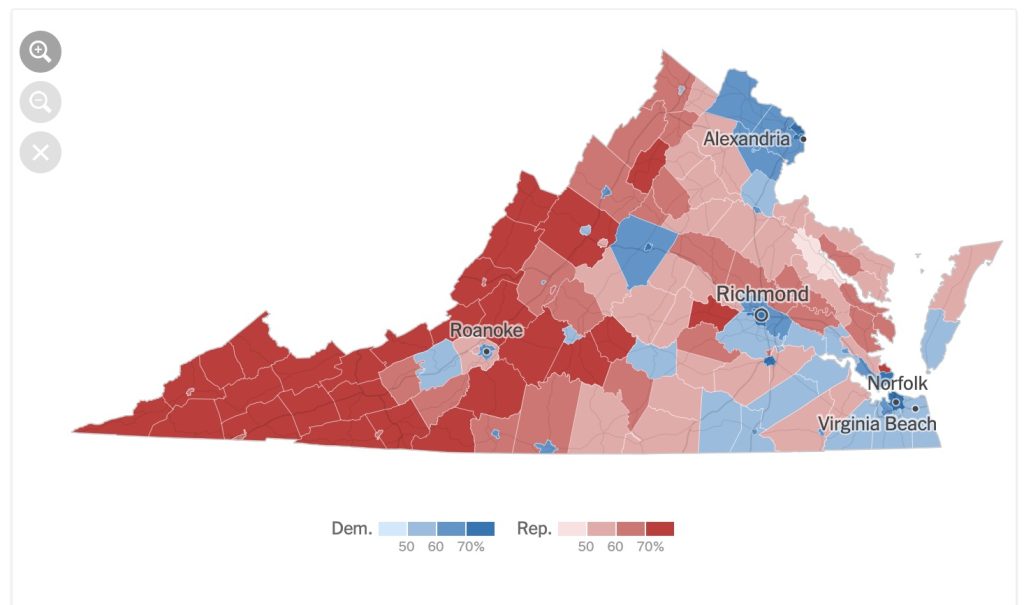

That little trip into history is because, of course, it rubbed off on us. During its founding in the 17th century, shires were set up in Virginia. These evolved into counties fairly quickly, and in the process we imported sheriffs. Virginia’s counties were established to put a state courthouse and sheriff within a day’s travel of every person in the state.

Cities had more specific charges–provide urban services like police, water, and eventually sewer. The cities were taken out of the counties so their taxes could be directed to these services. The cities could expand into the county, annexing land and extending services. This made independent cities the political equals to the counties, but had the competitive effect of removing tax base from the surrounding jurisdiction.

Virginia has independent cities to this day and their relationship with counties is squirrelly. Structurally, some county seats are actually politically separate from and equal to the county they administer. Salem, Virginia is the county seat for Roanoke County, but independent from the surrounding Roanoke County and the neighboring (also independent) Roanoke City.

Socially, the process of a city annexing county land was blisteringly contentious. The city-county relationship became so toxic that, in 1975, the state established a “temporary” moratorium on city annexations. This was also the last time new independent cities were created, with Manassas and Manassas Park. That moratorium was recently extended to 2024.

In many parts of Virginia, independent cities are experiencing fiscal stress, even before the pandemic. Thriving non-city communities like Tysons Corner and Leesburg have settled into their places within counties. Since 2000, two independent cities have reverted to become incorporated towns within their parent counties. Other cities are looking to do the same.

Good Morning Baltimore

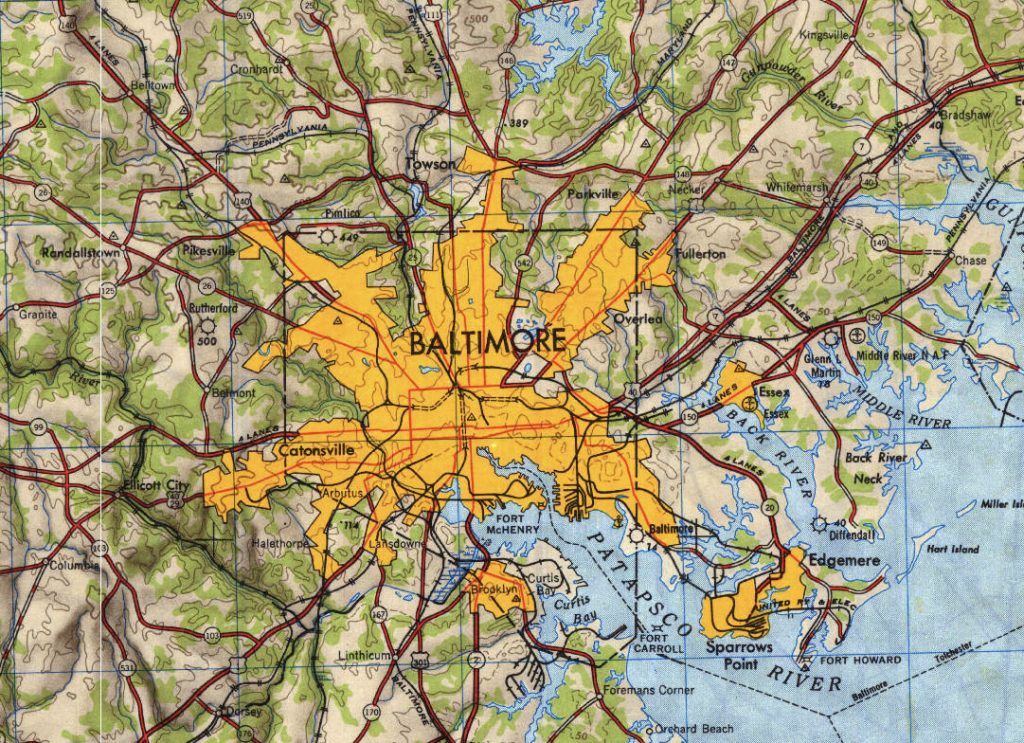

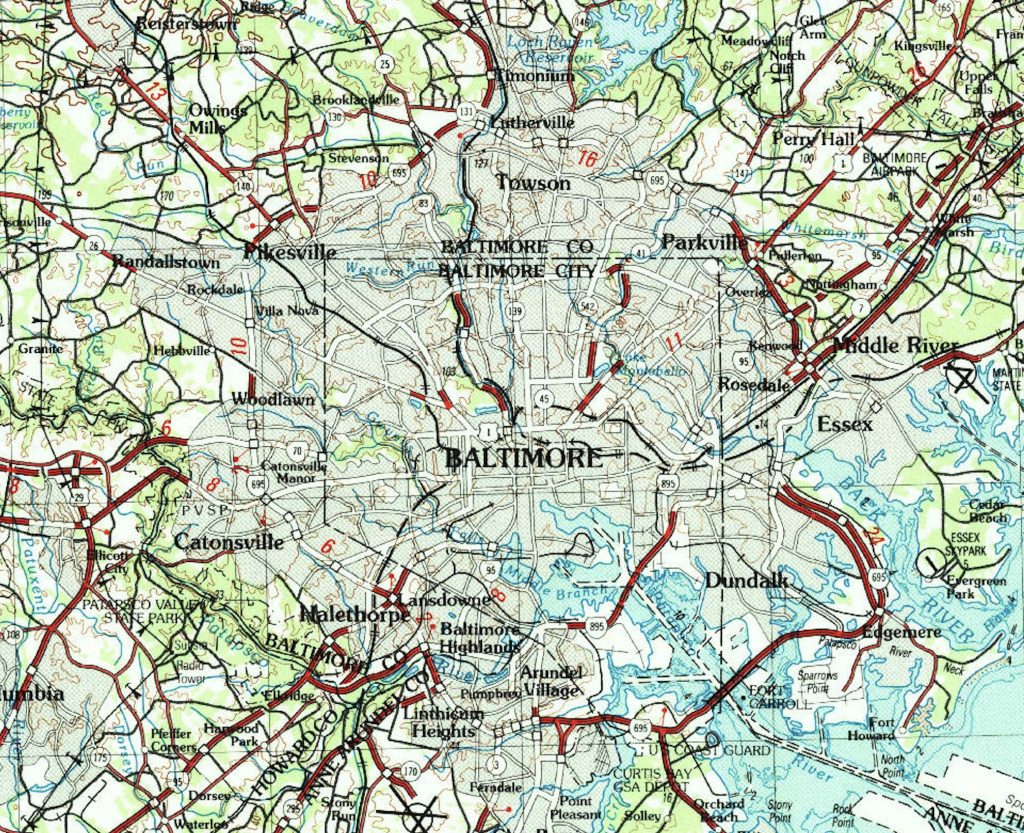

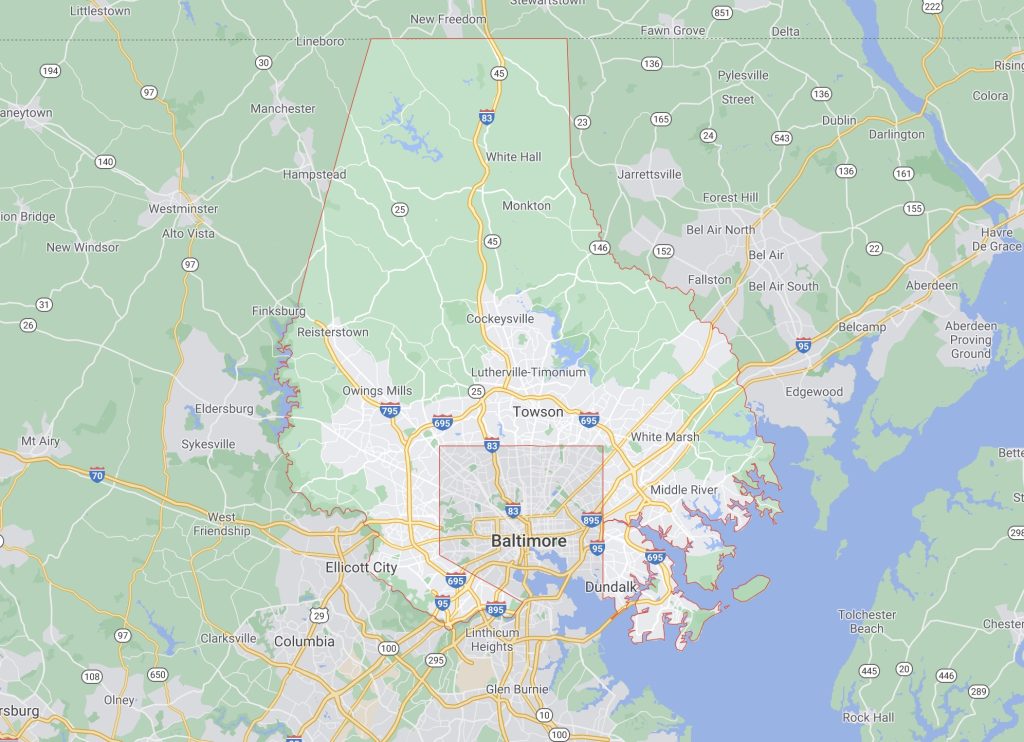

A more explicit argument against large independent cities is an hour up the highway from Manassas (or three hours in traffic). In Maryland, Baltimore City and Baltimore County have been separate entities since the city was incorporated in 1796. The boundaries are set in Maryland’s Constitution, last changing when the City expanded to its present borders in 1918.

As a native Baltimorean and resident for many years, I love the City. Any place that produced Cab Calloway, Barbara Mikulski, and John Waters is one of the most gleefully genuine cities in the world. And you can just stop if you think your seafood is any good.

But Baltimore is a damn political basketcase stemming from decades separated from an ever growing region. The eight-mile-by-eight-mile boundary of the city seemed totally adequate to absorb growth when most of it was happening along streetcar lines. That didn’t last long as Americans turned to cars. One independent city did not stand up well to 23 other counties clamoring for road construction in the General Assembly. After the Second World War, the counties surrounding Baltimore took that road funding and put it towards connecting then rural bedroom communities with highways.

Those bedroom communities turned into suburbs turned into urban clusters of their own right. For example, my alma mater is UMBC. Developed in the 1960’s, the University of Maryland Baltimore County could have been located in Baltimore City, and frankly should have been an attachment to the downtown medical and graduate school. But the burgeoning suburbs and straight up racism put the school just outside the city line. Development of the county ossified the boundary around the city. In 1994, Baltimore County’s population passed Baltimore City’s.

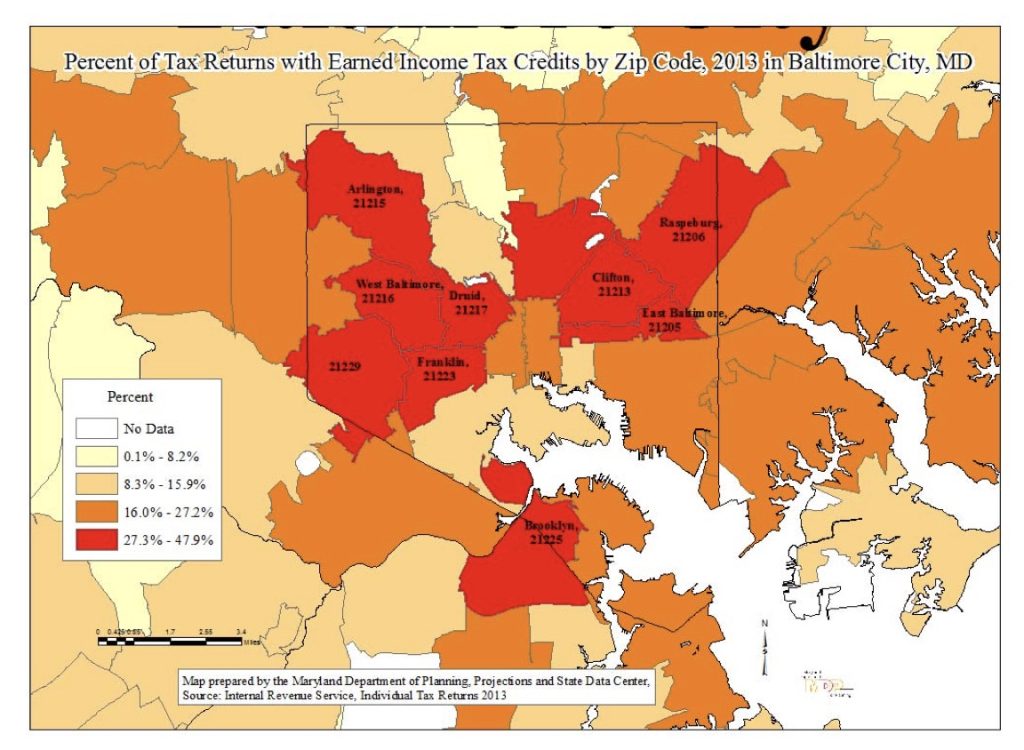

Race is an inexorable part of the equation. The City is 62% Black while the county is 29%. With that segregation comes all the flipped numbers. Homeownership in the City is 47% and the county is 65%. Median income is $49,000 in the City and $74,000 in the County. These numbers make sure that the separation is felt in other ways too. Baltimore County provides double the local funding of their school district than does Baltimore City.

Every few years, a voice pops up to promote merger between Baltimore City and County. Most recently, that came from Spencer Levy of CBRE, backed by research from the Abell Foundation. Their point is that the region cannot economically prosper without a “massive reset and a merger of its city and county governments.” Many contrary voices don’t oppose the idea, just point out that it’s going to be expensive political suicide. There’s no reason for Seattle and King County to cleave themselves apart and go down a road that Baltimore City and County find themselves trying to correct.

Couldn’t Happen Here

Of course, those cities Back East are in no ways comparable to the gleaming Emerald City. They lack economic development, suffered years of mismanagement, and have a long racist history. Nothing like what goes on here.

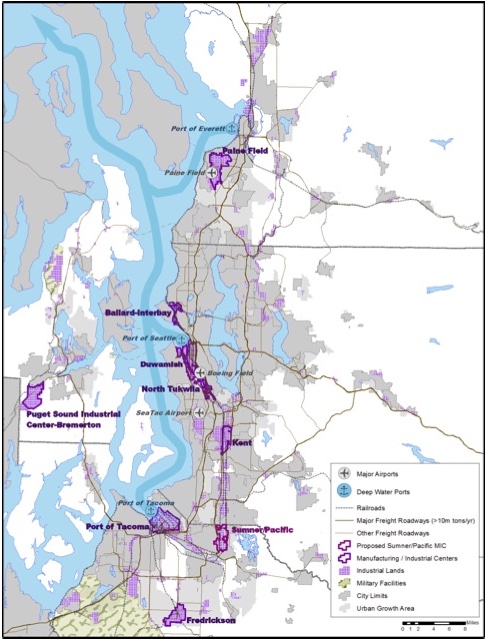

Admittedly, our city lines do strange things to our economic development. In Vision 2050, the Puget Sound Regional Council identifies a dozen growth centers and manufacturing centers and draws them as distinct dots on the map of the four regional counties. But when we pull back to look at the real space those dots cover, we can see the continuous line of industrial areas from Ballard-Interbay to Sumner/Pacific through the Duwamish, Tukwila, and Kent. Industrial Seattle covers ten jurisdictions and sections of two counties already. Adding another county boundary would surely improve some of that industrial loss.

And Seattle’s only had five mayors in seven years, the most recent insistent on gassing neighborhoods with chemical weapons. The city’s also at the center of a housing crisis, capitulating to armed gangs, and struggling to be solvent enough to pay for its bridges. Totally sound management.

And, of course, we don’t have a racist history in Seattle. The map of Covid cases in the city just happens to exactly reflect the 1936 redlining map. King County and Seattle do mistreat Skyway and White Center. They just happen to be predominately Black communities. So we don’t have anywhere near the race problem that they do back east.

We can go on. As has been noted, the difference between a prison and a fortress is which way the guards face. For cities, whether a boundary is good or bad depends on the direction of population flow. Cities are great proponents of strong inelastic borders when they’re on the receiving end of population. When the faucet stops and reverses, those boundaries are chokers. That’s what happened in Baltimore. That’s what happened in a lot of Virginia independent cities. And in Seattle, we have a history of booms and busts.

Lower the Walls

There would be one interesting effect of making Seattle its own county. Among Washington’s 300 school districts, Seattle’s would become the only one concurrent with a county boundary. This would be very in line with many of the counties throughout the South. The reason for them was very simple: racism. The school districts in the South needed to be large enough to maintain two separate school systems. County boundaries that reinforce school boundaries that reinforce service boundaries have created this country’s most severe forms of segregation.

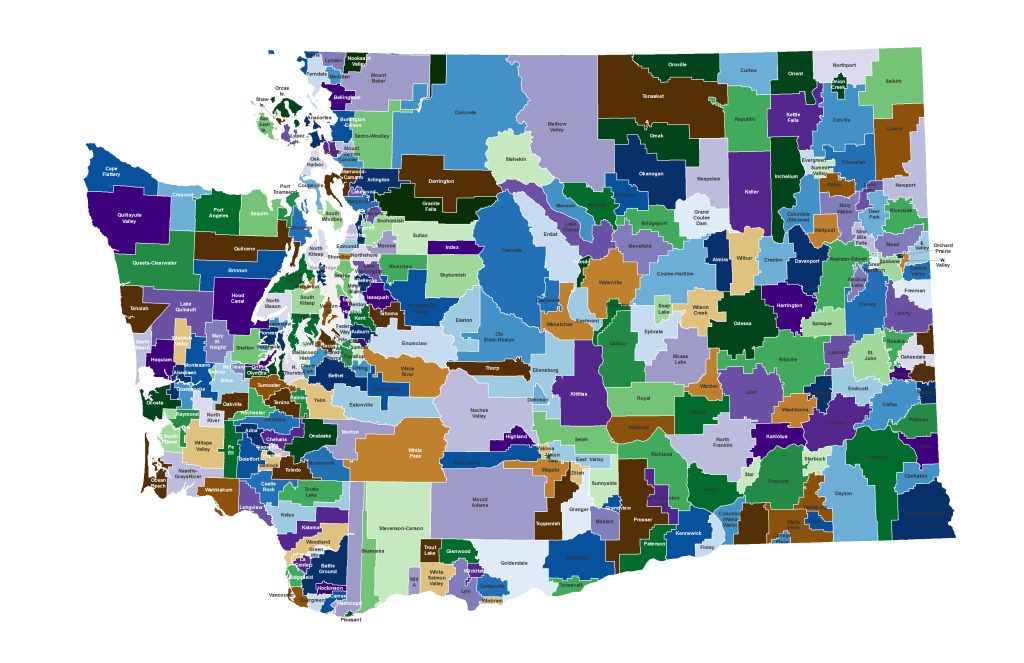

That kind of proves the point, though. If Seattle were to secede from King County, a whole lot of services would match the new county’s border. Policing, education, fire, libraries, garbage, and all the rest would not just be citywide, but countywide. If we’re looking for more equitable and responsive ways to do these things, perhaps the question isn’t whether Seattle should secede and become its own county. Instead we should ask why the current services don’t uniformly cover the whole of developed King County. Why are municipal services broken up and provided differently on one side of 145th Street than the other? How can we improve that?

During its last extension of the annexation moratorium, the Virginia General Assembly required a state commission to examine whether its independent cities should be allowed to resume annexation. The commission came to a hard no, calling a resumption of annexations “an ineffective solution.” They saw the animus and volatility of annexation leading to litigation and fiscal stress. “These scenarios would lead to a significant disruption in the lives and operations of many of the Commonwealth’s citizens and businesses, respectively, and run counter to fostering positive intergovernmental relations in the Commonwealth.”

Instead, the Virginia boundary commission recommended:

- 1. Modify reversion and consolidation statutes to remove obstacles.

- 2. Make reversion and consolidation more cost-effective through incentives.

- 3. Grant additional powers to counties through reversion and other interlocal agreements.

- 4. Evaluate mandated service delivery methods to identify appropriate service level.

- 5. Relax the requirements for the establishment of joint authorities and special districts.

- 6. Provide planning grants to explore interlocal agreements and other operational efficiencies.

- 7. Evaluate adequacy of local fiscal resources to identify enhancements.

- 8. Create or expand programs to reduce local fiscal stress.

- 9. Incentivize additional regional cooperation and regional programs.

Virginia is not trying to make new counties. The state that set up many of the norms for counties on this continent is now talking about winding down those boundaries and cooperating regionally. Those are the new experiments in democracy, not reinforcing tired old lines.

Any line, even if developed for the most austere administrative reason, will become a method of segregation. Lines are important for all sorts of reasons, so we have to draw some of them. Our job should be to minimize the number of lines and lower the stakes of being divided by them. Being caught on one side or another should not determine a person’s education potential, future earnings, or lifespan.

If Virginia sees that tougher, more impenetrable boundaries are not the route to healthy jurisdictions, Seattle should take some notes from their 200-year head start. Seattle’s boundaries are already screwed up. Our residents and jobs and goods flow freely across the city line. We should be looking for ways that tax money and services and good governance can do the same. Take those down those city borders rather than etch them in stone.

Read AJ McGauley’s counterargument making the case for a separate Seattle county here.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.