Growing up in the Old Northwest, I was used to townships and counties being small, arbitrary but generally orderly boxes that operate as the base unit of rural government. Around Indianapolis, the suburbs grew such that school districts, municipalities, and townships were generally contiguous, imbuing place into previously meaningless squares on a map. Indianapolis, the largest city, outgrew Central township and merged with Marion county in 1970.

King County is enormous, the twelfth most populous county in the United States despite roughly a third of the county being uninhabitable mountains. Large counties make good sense when public services need economies of scale in the sparsely populated Columbia plateau, or when a county can fully capture an urban area like Thurston, Whatcom, or Spokane. King County, however, sprawls while failing to encompass Greater Seattle.

The City of Seattle, which is well on the way toward 800,000 residents, would be the fourth most populous county in Washington all by itself. With my experience in Indiana, I have wondered why Seattle wasn’t already a standalone entity, particularly as Seattle already operates independent of King County in many ways by virtue of being both large and old, providing its own electricity (Seattle City Light or SCL), libraries (SPL rather than KCLS), and parks (King County manages no facilities within city of Seattle, though the current parks levy does invest in Seattle alongside the rest of the county). Interestingly, SCL and Seattle Public Utilities (SPU) boundaries are not contiguous with the municipal boundaries, but neither are the King County water treatment boundaries, which highlights how we optimize rather than align jurisdictional boundaries.

Why change?

Seattle is the clear center of the region, but we are not a monocentric agglomeration (think Chicago). Our regional vision is for Bellevue, Tacoma, Everett, and Bremerton to be metropolitan cities alongside Seattle. Separating Seattle would structure our political subdivisions to better reflect this vision.

Elevating the Seattle mayor to be coequal to county executives would should right-size our regional discourse and better place Seattle to interact with its immediate neighbors to the north, south, and east. For example, population, a crude measure of proportionality, would be more balanced four ways rather than three (Snohomish and Seattle at about 800,000, Pierce at 900,000, and King excluding Seattle at 1.5 million). Rather than one dominant entity surrounded by economic supplicants, giving Seattle and King coequal seats at the table both shift power away from a single entity while also elevating Seattle and King in our regional structures.

The current Seattle city boundaries are arbitrary, as are many county boundaries. Whether the boundary should be adjusted is an interesting question I will not delve into, but there should be a boundary. Even if we merged Central Puget Sound into one “city,” we would need underlying political units. We can call them boroughs to fulfill our destiny as the new New York City, but we would eventually reinvent the wheel under a new name.

There are very few urban problems that need to be tackled at the county level. The big problems facing our region–transportation and housing–cross county lines and require coordination with neighboring counties whether Seattle is contained within King or is standalone.

So then why not shift everything to the regional level and call it a day? In a word, subsidiarity.

Subsidiarity

Subsidiarity is a framework in Catholic Social Teaching that was developed to find a third way between fascism/socialism and laissez-faire liberalism. “Subsidiarity is an organizing principle that matters ought to be handled by the smallest, lowest, or least centralized competent authority,” the Wikipedia entry states. Our federal structure that devolves all unenumerated powers to sovereign states rests on the same principle of Subsidiarity.

In an urban context, the principle would suggest we should attempt to tackle most issues at the neighborhood level and then work upwards for issues that cannot be resolved at that level. For example, zoning and land use decisions should generally not be at the neighborhood level for political reasons, while public works departments should generally not be at the neighborhood level due to economies of scale.

The framework, however, does not mean that every neighborhood is an independent city. Carnation is a standalone municipality because of its geography and should remain that way. Medina, on the other hand, is likely better organized as a community council within Bellevue, akin to the East Bellevue Community Council, rather than an independent city.

Why Seattle?

Why, then, is “Seattle” and “Not-Seattle” an important delineation in the hierarchy of competent authority? I posit there is a cultural and political break between Seattle and the rest of the region. I won’t dwell on the political science–I don’t understand why Seattle votes socialist while Burien, Bremerton, and Bothell do not–but the discontinuity is apparent.

A vibrant example that comes to mind is safe injections sites; disagreement is more about culture than science. Seattle and the rest of the region have sharply divergent views on how to move forward with improving public safety and public health and both entities should be enabled to follow their respective values. But the difference does not simply need to be around the hot-button issues of today. For example, let’s address public transit:

- Technical differences: When pursuing electrification, Seattle can expand upon the trolleybus network, while Not-Seattle must focus on conversion to an electric battery fleet.

- Structural differences: The suburban built environment is likely more conducive to various microtransit innovations, while Seattle has the density to focus on high quality fixed route transit and does not need to be distracted by the latest microtransit fad.

- Goal differences: Seattle would focus on creating a high frequency grid and maximizing the population within it, while the county would likely structure express service oriented to maximize productivity and local service oriented to maximize coverage, with an equity framework to address the inevitable tradeoff.

As shown in the structural differences, Seattle can strive to have its cake and eat it, while not-Seattle is differently constrained and needs to spend political energy grappling with. Differences in geography and built environment not only limit and guide our policy choices, but they also direct our political energies to address different dilemmas.

What next?

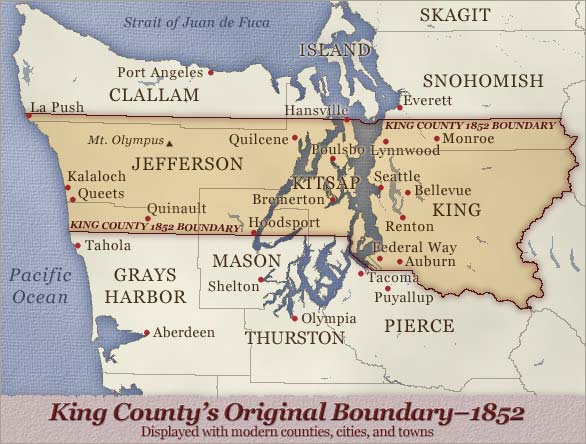

Washington has a long history of carving new counties out of existing counties.

Washington has created new counties through history, gradually evolving from one county to 39, but a new county hasn’t been created since 1911, so any next steps would be wildly speculative. Which city would host the county seat? Kent, alongside existing court and detention facilities, or perhaps Renton, as the bridge between South and East King? Do we also shuffle other boundaries? Skykomish to Snohomish, please!

Major assets would presumably be divided by geography, but it will not be a clean process. For example, the King County Metro North Base sits outside of Seattle city but serves Seattle routes; who owns it? Some assets will need to be duplicated. Seattle will likely consolidate city and county administrative facilities into a single downtown campus, requiring King County to stand up new administrative facilities elsewhere at considerable expense.

Nonetheless, I believe establishing Seattle as a standalone city-county, independent of the remaining King County but closely integrated with King, Snohomish, Pierce, and Kitsap counties, would be a positive evolution for the region.

This is a two-part series weighing the pros and cons of Seattle becoming its own county. Here is Ray Dubicki’s article arguing against the proposition.

AJ McGauley

AJ McGauley was a temporary transplant in the Seattle area, living in East King with his lovely wife for five years before returning to the great Midwest. Having lived in nine very different cities in the six years prior to moving to Washington, he discovered the wonky side of urbanism after reading The Urbanist and is interested in why cities grow (or don’t grow) in different ways. He worked for Sound Transit and can still be found riding transit for fun.