In September, King County Metro filed a report on their battery bus implementation plan. Like the Kenmore water taxi report, this paper is the result of a proviso within the 2019-2020 King County budget. The County wanted Metro to discuss major milestones for the 2021-2022 biennium, procurement plans and infrastructure schedules through 2040, cost projections, study and evaluation of battery bus implementation, and a preliminary high-level financing planning in the battery bus plan.

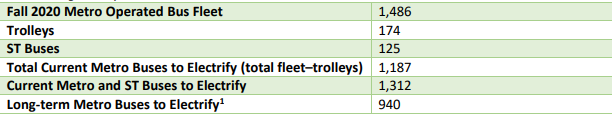

Metro’s battery electric bus (BEB) evaluations began with a 2016 purchase and operation of three short-range BEBs in Bellevue. The short range buses have a 25-mile range and 10-minute charge. The agency’s electric bus program currently exists with 174 trolleybuses, a small fleet of 11 short-range Proterra BEBs—expanded from three—recently concluded testing of 10 long-range but slow-charging BEBs, and an order of 40 long-range (140-mile range) BEBs from New Flyer. Today, 12% of Metro’s fleet is zero-emission buses.

The new buses will be supported by a new South Base Test Facility that will open in January 2022, roughly when the buses will begin operation. Close by, a new interim base at the south campus will be electrified in 2025 and be able to support 105 more battery buses. South King County will host this fleet first as the region is worst effected by air pollution, as discovered by a 2017 study. The study also provided the basis of Metro’s 2040 target for a zero-emission fleet, which the analysis showed would be attainable.

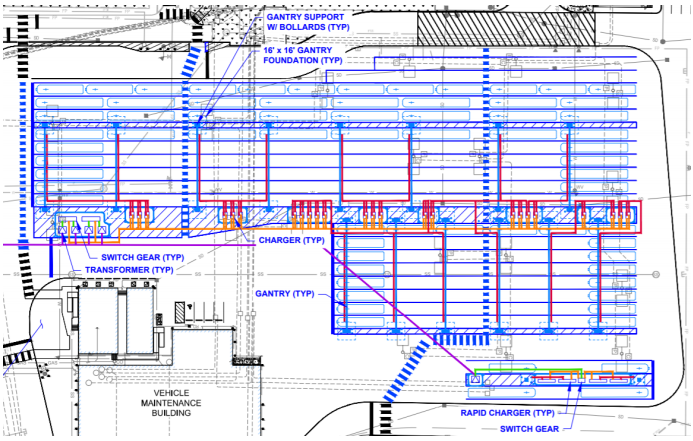

Testing completed in 2020 showed expected and above-expectation performances from the 40-foot buses for range, and a 60-foot New Flyer bus was able to outperform current diesel hybrid buses in snow due to a multi-axle configuration. Cold weather is where performance struggled for the BEBs. Drivers were also happy driving the BEBs. Study on electric base conceptual design found that a “Bridge/Gantry” designed base performed the best overall, and was dominant in future-proofing and efficiency.

The implementation plan was developed with all of Metro’s findings in mind, but also with Covid impacts and no additional funding sources in mind. In Metro’s assumed trajectory for the report, service reduction will occur in 2021 exacerbated by expiration of the Seattle Transportation Benefit District—thankfully that’s been renewed and augmented with a $20 car tab fee passed by City Council. Impact from the pandemic will result in service reduction between 2024 and 2027. A countywide transportation ballot measure was supposed to give Metro the resources to grow their fleet to 1,800 zero-emission buses in 2040, pandemic uncertainty pushed the County Council to delay the effort. Worryingly, with Metro’s gloomy outlook its 1,187-bus diesel-hybrid fleet would shrink to 940 battery buses by 2040. That’s a loss of more than 200 buses from today’s fleet. The electric trolley fleet would grow from 174 to 204 for a total of 1,144 Metro coaches in all. Light rail expansion will pick up some of the slack, but buses will still be essential for feeder and local service–not to mention RapidRide expansion plans–so shrinking the fleet hardly seems wise.

The Timeline

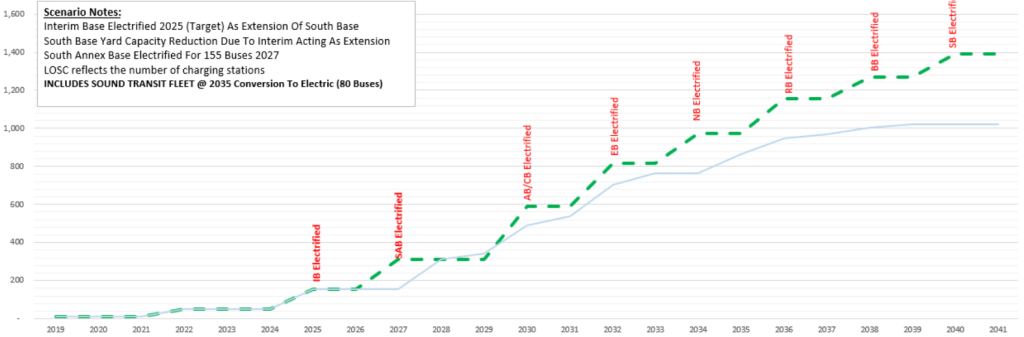

In their implementation plan, Metro outlines two timelines for a completely zero-emission fleet. One finishes conversion by 2040 and the other in 2035, acquisition plans are the same for the two plans up to 2035. The 2040 timeline opts to space out the bulk 2035 order that the 2035 plan leaps for. In addition, the last new 13 diesel-hybrid buses will arrive in 2023 for RapidRide G‘s completion, and Metro plans to expand the trolleybus fleet by 30 buses in 2029.

Simultaneously, Metro would also be constructing capital upgrades to provide charging infrastructure to expand BEB capacity. Here the 2035 implementation plan accelerates the BEB infrastructure timeline to provide capacity for 1,393 battery buses in 2037 rather than 2040. Problematically, this timeline also limits the ability to expand the battery bus fleet between now and 2030, as capacity and projected fleet size closely follow one another until the mid 2030s. Even if the fleet was the same size as Metro’s projected capacity, we wouldn’t be able to even return to today’s fleet size until 2036 in the accelerated 2035 timeline if Metro adheres to a zero-emission fleet.

Somewhere in the timeline, a more sophisticated charge management system will also be developed and implemented to optimally charge a burgeoning fleet of BEBs and control electricity costs and usage. This will involve a system of chargers, battery packs, and software to minimize charging during peak electricity demand, prioritized buses to require more charging, and automatically lower or stop power levels to buses that do not require more charging. This is aided by the mix of short-range/quick-charge and long-range/slow-charge buses that will help increase the flexibility of the system.

The cost of electrifying the bus fleet

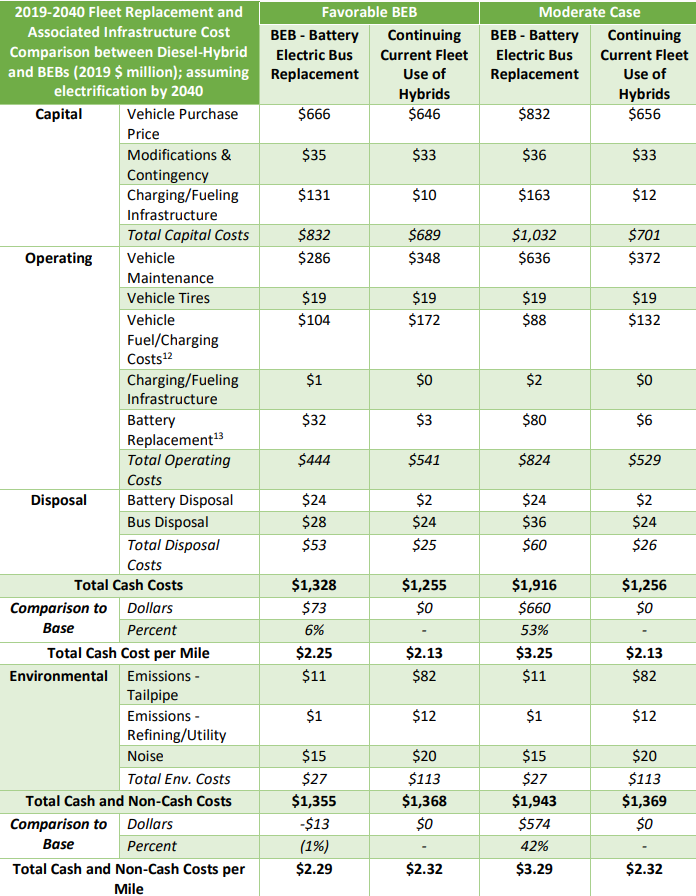

This fleet and infrastructure update will be by no means cheap, two cost scenarios are run to update 2017 results that initially found a 6% increase of Metro’s life-cycle costs for a zero-emission fleet transition. The difference went down to 2% when factoring in societal costs like emissions and noise. These numbers are mirrored in Metro’s favorable BEB scenario, where input variables are adjusted to favor battery buses and the only difference is that BEBs are 1% cheaper than diesel-hybrid buses when considering societal costs. Positives begin to evaporate when Metro runs down the costs in the moderate scenario that the agency is most confident in as an accurate estimate.

In the moderate case, battery buses would cost around $1,916,000,000, or 53% more than hybrid buses, in 2019-2040 lifecycle window, and 42% after societal costs. That respective cost differential translates to 270,000 and 237,000 service hours over the 19-year period. According to the report, “The analysis assumes fueling and charging infrastructure are amortized over the life of the infrastructure. Electrical infrastructure has an assumed asset life of 40 years, direct vehicle charging infrastructure has an assumed asset life equivalent to the vehicle life of 15 years, and diesel underground storage and pumps have an assumed asset life of 40 years. Additionally, the costing is based on maintaining the current diesel-hybrid fueling infrastructure compared to building new BEB charging infrastructure.”

Discussed in detail is Metro’s confidence that operating costs for battery buses will be greater than hybrids. This goes against typical expectation that electric is cheaper to operate than hybrids. They point to underestimation of infrastructure costs in the 2017 study, as their data has improved. Maintenance costs are acknowledged as volatile and possibly cheaper than hybrids. The agency also specifically addresses a June 2020 study by the National Renewable Energy Lab that found that BEBs would make up the difference with hybrid buses after three years. They note that the results aren’t applicable to Metro as the lab uses retail prices of diesel versus wholesale cost, the modeler’s declining costs compared to expected increasing electricity costs for Metro, Metro’s higher estimates for equipment costs, and the inclusion of grant funds that Metro sees as unreliable.

On grants and funding, the agency has historically funded fleet acquisition from cash and grants. Debt financing, leasing, and even private partnerships are also presented as options. A specific financing plan isn’t present in the plan, but the agency notes that new revenue and various financing methods would be needed to fund the task of transitioning the remaining 89% of the fleet to zero-emission vehicles.

King County Metro ends the report on their proposed 2021-2022 budget to support 260 battery buses by 2028, and their commitment toward a zero-emission future. As nice as that sounds, the agency’s report paints a rather bleak future with a smaller fleet and an expensive transition to a zero-emission fleet. This future only exists in a world where the County and its residents don’t properly support the agency’s public transportation.

Without additional funding, the County will go in the wrong direction in a world where car tires are collapsing local salmon runs, and vehicle miles traveled needs to drop 30% by 2030 to keep global warming under 1.5° Celsius even in the optimistic scenario where the United States adds 50 million electric vehicles by then. Hopefully, a countywide transportation ballot measure is able to materialize to help both electrify and increase the service hours of Metro. Otherwise, I’m not sure if the cost of electrification is worth the service hours we could get with a hybrid fleet.

Clarification: This article has been updated to note the expected fleet of 204 electric trolleys in 2040.

Shaun Kuo is a junior editor at The Urbanist and a recent graduate from the UW Tacoma Master of Arts in Community Planning. He is a urban planner at the Puget Sound Regional Council and a Seattle native that has lived in Wallingford, Northgate, and Lake Forest Park. He enjoys exploring the city by bus and foot.