Seattle is amidst its most important transportation investment in 100 years. And—to no surprise—some neighbors have a problem with it. Seattle is well known for short-sighted skepticism towards robust transit investments, but never seem to gripe about the high cost of subsidizing automobile supremacy.

While these residents of West Seattle ignore the risk and expense associated with slapping a band-aid on the West Seattle Bridge, there is careful line-item review of Sound Transit’s Link light rail expansion into their neighborhood. Rather than showing enthusiasm for getting a quick and sustainable connection throughout the Seattle Metro region, some neighbors see the expansion as a disruption and a waste of money.

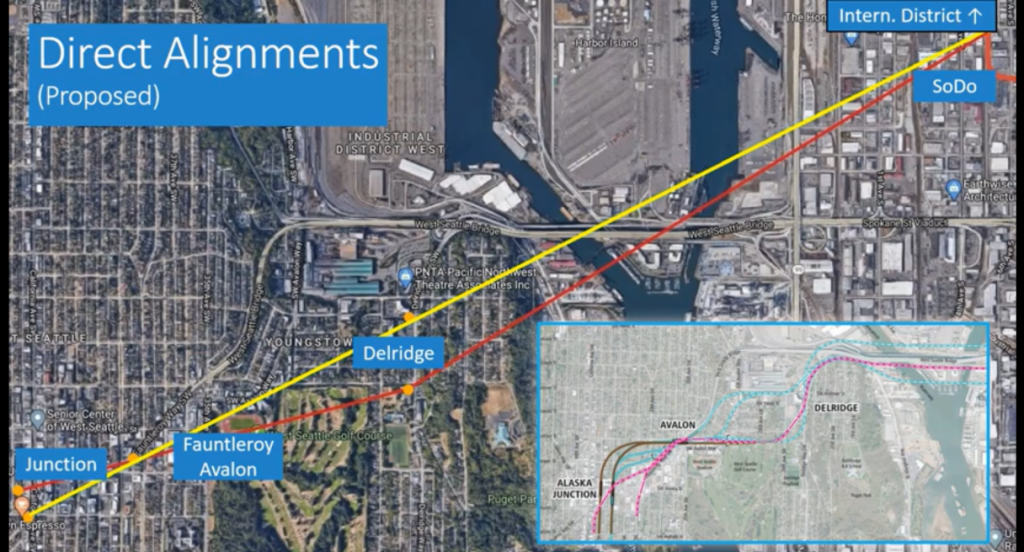

As this light rail expansion is in the planning stages for West Seattle, the effort to sow discord and discredit the plan has enlisted neighbors to propose an urban gondola in its place. Citing cost and schedule, the pragmatic locals see Link as a junket. They focus their complaints about station sizes, train noise, guideway height, and lost street parking. If the desire is to bring transit solutions faster to the peninsula, perhaps advocating for a Sound Transit-ready bridge–speeding up light rail by five years–is the right strategy. Proclaiming the gondola will be operational by 2024 seems unrealistic considering Sound Transit must study the capabilities for building and operating it. That hasn’t begun and wouldn’t even start for another year.

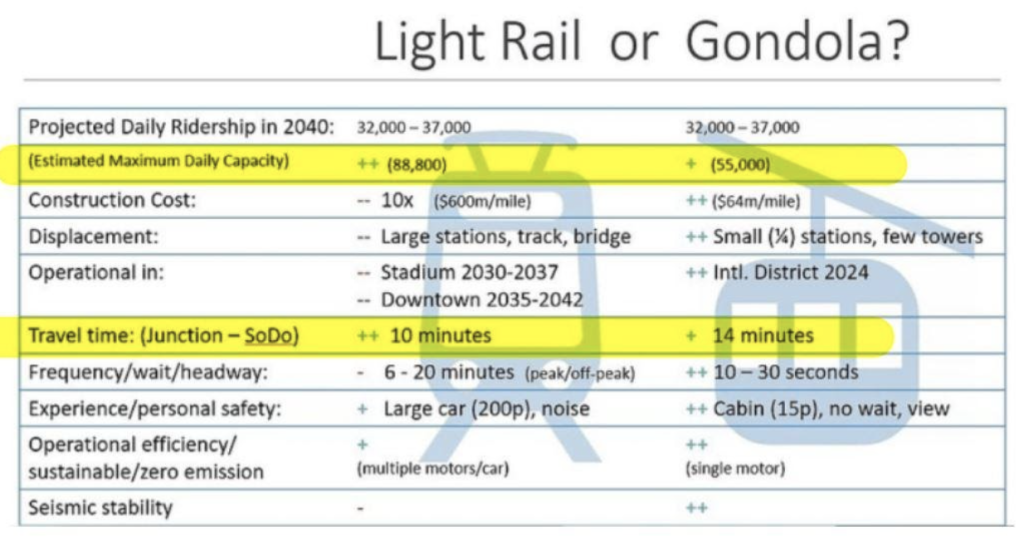

The reality is that the gondola will take 40% longer than Link to get downtown and it carries 38% less passenger capacity than light rail. The local activists praise the 30-second frequency of gondolas over the six-minute wait time for a train (Sound Transit’s four-car trains carry 800 people with six-minute frequency planned at peak). The gondola system that they have proposed can only carry 360 passengers in six minutes. So, while the frequency sounds great, the reality is it will take nearly 15 minutes to move the same amount of people light rail will, thus, half the frequency. Then a gondola would dump riders in SoDo or International District Station (if manages to make it that far) for a transfer, adding another time penalty.

And yet, the West Seattle proposal still praises urban gondolas around the world as cutting-edge, catch-all transit, citing examples in Europe and South America, even though they are best suited to niche transit problems.

Gondolas promise to be cheap, but they routinely face cost overruns and significant operational costs. They also promise transformative high frequency solutions that don’t deliver the same level of ridership as other technologies and don’t fundamentally address other urban problems. If light rail plans to move more than 30,000 people with twice the frequency during rush hour, then a gondola taking twice as long will only convince people to get back in their cars creating more menace and congestion on our streets. Part of the problem is gondolas take a simplistic approach of avoiding the root problems of planning streets. Light rail may be elevated, but it still works within the grid and helps solve over-dedicating street space to cars.

A particularly oft-cited urban gondola example is Medellín, a city with a unique use case. Having five lines that fan out from mainline transit, the gondolas reach and bypass informal settlements (barrios, colloquially) in very steep, hard-to-reach hillside terrain. These informal settlements would require complicated routes and infrastructure to reach with a bus or train. Here, a gondola system makes sense by reaching communities directly without plowing through them indiscriminately.

But ridership of Medellín’s gondola system is hardly worth mentioning, carrying just over 50,000 daily riders–16 million in total ridership in 2019. That’s comparable to Seattle’s three RapidRide bus lines–the C Line included–that together carry more than 43,000 people per day in a normal year. That ridership further disappoints considering that Medellín has twice the density of Seattle (clocking in at nearly 18,000 per square mile to Seattle’s roughly 9,000 per square mile) and an overall population of 2.7 million. Medellin’s busiest gondola line (Line K) manages 30,000 daily riders, but the others see middling ridership.

West Seattle’s Link expansion, which may require purchasing a few $800,000 homes for market value, is not the same type of complex, informal settlement or inequitable displacement. Nor, as activists have admitted, would it be faster service. It also certainly is not cost-prohibitive or an engineering challenge from a topographical standpoint for light rail.

The West Seattle light rail line, however, is not the end of the system. There has always been a vision to expand it further south to serve communities like High Point, Westwood, Highland Park, White Center, and Burien. Future expansions could also bring the line near the airport and reach Tukwila, Renton, and beyond. A gondola could certainly be expanded to serve those communities, but the mode would operate at slow speeds and falter from capacity limits.

Link’s system already carries 26 million passengers per year. Over the next five years, another dozen stations will open. This overall network is critical to create both the urban and suburban commuter rail network needed for sustainable travel. Abandoning it now to gamble on a low-capacity and difficult-to-expand system would be yet another shortsighted transportation mistake.

Voters approved light rail expansion as part of Sound Transit 3, and many live in West Seattle. They did not vote for the chance to throw it all away because a few neighbors are mad about losing parking and train noise. Link is a starting point for a much broader system expansion. In fact, Link is so popular that Seattle Subway is already working to shape a fourth transit package. After a handful of stations are opened this fall in North Seattle, popularity of the network will only grow. Rather than asking for gondolas, neighborhoods along Aurora Avenue–areas currently with the highest bus ridership in the state–may be asking for their own light rail line. Hey, wait a minute, they already are.

Ryan DiRaimo

Ryan DiRaimo is a resident of the Aurora Licton-Springs Urban Village and Northwest Design Review Board member. He works in architecture and seeks to leave a positive urban impact on Seattle and the surrounding metro. He advocates for more housing, safer streets, and mass transit infrastructure and hopes to see a city someday that is less reliant on the car.