Comprehensive updates pushing the 30-year-old Growth Management Act to be adaptive, inclusive, equitable, and actionable.

When the Washington legislative session begins in less than a month, the budget and the response to Covid will be at the top of the agenda. It is a tall order to break through these dual massive issues, but at the front of the line will be the first comprehensive update to the Growth Management Act (GMA) since it was adopted 30 years ago.

“Every session covers multiple topics,” Representative Joe Fitzgibbon (D-34, Vashon and West Seattle). “We need to be able to work on more than one big problem at once. We’re also going to have commitment as Democrats to make progress on climate, equity, and racial justice. The Democratic Caucus priorities are Covid relief, racial justice, budget, and climate. Clearly reforms to GMA cover those priorities.”

Fitzgibbon’s House Energy and Environment Committee recently heard presentations from a technical effort that has been underway for several years to identify gaps in the GMA. A group of stakeholders and active GMA users highlighted issues with the Act. Now they are bringing legislation to this constrained session that will fundamentally change the way planning, growth, and conservation function in Washington.

Road Maps

Getting to the point of proposing legislation has been a multi-year process of outreach and engagement. Starting in 2015, the legislature requested and then funded a combined effort by Washington State University and the University of Washington (UW) to convene statewide workshops for groups working with the Growth Management Act.

Instead of the constant stream of small changes being proposed, the legislators asked for something comprehensive. The scope of the issue became apparent. “Talking to people across the state, the workshops came up with four volumes,” University of Washington Professor Joe Tovar said.

Professor Tovar has a deep working knowledge of the GMA, having been part of drafting the act, then sitting on Washington’s Growth Management Hearings Board, then practicing planning in the public and private sectors for several decades. The four volumes of issues were released in 2019 as A Road Map to Washington’s Future, with Tovar a Co-Lead.

The Road Map shows an evolution in the way counties and cities operate within the state’s growth policy framework. The report developed guiding principles based on the many responses. They delved into concepts such as respecting that place matters; maximizing flexibility, adaptation, and innovation; taking a bigger picture of systems; and maximizing collaboration.

“It was different 30 years ago,” Tovar said. “There was a strong belief that the state role should be very passive.” That strong belief translated into our “bottom-up” GMA with protections for local control and barriers between the jurisdictions and the state boards arbitrating GMA issues.

He cited an example of an appeal of a local decision coming before the Growth Management Hearings Board. “When the board says you didn’t comply, it just gets sent back. The Board cannot say ‘this is what you do to fix it.’ They just say ‘that’s the wrong rock, see you in six months.’”

The wall between the board and the localities is part of the longer wall preventing the state from helping cities with more complex issues.

“Bottom up has its merits. Most things fit,” Tovar said. But some issues are regional in nature. “Things like regional housing, it’s hard for a city to respond to a regional need. They don’t have enough influence, let alone data. GMA is not set up to deal with it effectively.” The state has a compelling interest to improve local plans with regional information.

For the last year, with a push but few resources from the legislature, he has been convening a group started by the Road Map. Every other Tuesday during a pandemic, the group has worked to translate the four volumes into legislation.

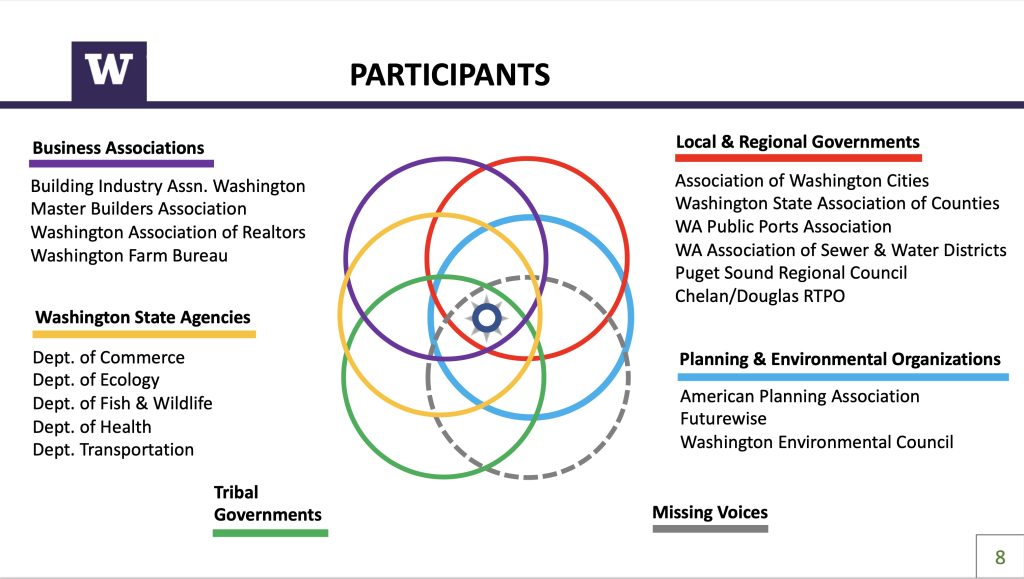

Before we even get to the specifics, the ongoing nature of Professor Tovar’s Tuesday roundtable cannot be overstated. He has not just drawn together a conclave of agencies, tribes, jurisdictions, associations, and organizations. He’s done it with an eye towards those not in the room. Too often, the limited nature of towns and cities prevents that dialogue, or the complexity of regional bodies limits who can attend.

This unique arrangement has produced a draft document that responds to longstanding barriers in the GMA as well as the tumultuous hellscape of 2020. Proposed language from the group goes beyond the always present cities and counties to include regional agencies and tribes. That the group is a continuing dialogue is itself impressive. That they are now proposing legislation with provisions for getting more people in the room is an achievement.

Without broadcasting it, Professor Tovar’s process of translating the Road Map is actually showing that including missing voices is itself a regional issue of compelling state interest.

Safe Harbor

One place where the relationship between localities and the state could change is the proposed Safe Harbor provisions. “I don’t like the term Safe Harbor. I prefer to call it what it is, which is Acknowledgement.” Unfortunately, the battle over names may be one that Dave Anderson, Managing Director of Growth Management Services for the Washington State Department of Commerce, may have already lost. Most people are referring to the provision as Safe Harbor.

In operation, it is very easy to see where Anderson is coming from. From his perspective at the state, his office will formally acknowledge that a jurisdiction took the right steps when adopting development regulations or plans. If a jurisdiction receives that acknowledgement, the Department of Commerce will step in to defend the jurisdiction against appeals.

Anderson said the Road Map showed how cities and counties were concerned “about the cost and delay of appeal with the plans, particularly with new issues they are being asked to take on. Housing, climate change. One of the major concerns is fear of appeals.” Local governments are looking at the issues where concern is tipping to crisis and seeing the expense of fending off litigation.

So the state looked for inspiration from two counterparts. In Oregon, there is formal approval by state agencies that a locality has correctly adopted plans. The other example, much closer to home, is Washington’s own Shoreline Management Act which includes an approval of local government actions by the Washington State Department of Ecology.

This gets into the mechanics of administrative law. Currently, an appeal to the state’s Growth Management Hearings Board is between a party that does not like a land use decision made under the GMA and the town or county that made the land use decision.

Under Safe Harbor, the jurisdiction’s GMA decision has been reviewed by the state before it went into effect. When a party appeals that decision, they’re no longer facing a town. They’re facing the Washington State Department of Commerce. State decisions receive greater deference.

Safe Harbor is not designed to be a carte blanche for all actions by cities and counties. First, the process is voluntary. Jurisdictions do not have to submit their plans and regulations for review by the State. This is a nod to the GMA’s traditional bottom-up structure.

Second, Safe Harbor is reserved for a short list of municipal actions. Plans and regulations related to critical areas, urban growth boundaries, housing, resource lands, and siting public facilities. It is a list developed to encompass the smallest number of different items and catch the most appeals. Like the 80/20 rule, this short list would cover at least 80% of situations. Anderson said. “They’re the handful that represent the overwhelming 90/10 more like.”

There is a deeper logic to the state’s Department of Commerce recognizing these specific actions by a locality. Each of these actions is “a place where the statue clearly stipulated a state interest combined with a set of requirements that rely on really complicated facts.” These are hard questions that the state wants localities to answer well.

Anderson points to critical areas, where specific legislative requirements combine with complicated sets of facts and evidence. For small towns, this occurs in an environment that is politically difficult for local officials. The state can work with the jurisdiction and bring its expertise and its extensive collection of data from beyond the jurisdiction’s limits.

“When we see an ordinance, we can consult with agencies that have expertise, who have developed the recommendations. We can ask, ‘is this consistent with the science?,’ and make that assessment before it goes into the appeals process. ‘Is this going to be enough?’”

Together, the Safe Harbor provisions provide both protection from appeal and data to reinforce decisions. Which may be why Anderson recognizes his “Acknowledgment” name for Safe Harbor isn’t going to stick for cities and counties. “They’re not alone in that appeal process any more. For them, it seems like a safe harbor.”

Net Ecological Gain

Sections of Washington’s land use framework, particularly efforts to protect critical areas, rely on a legal standard called “no net loss of ecological function”. Conceptually, this means that after a plan or development, the existing condition of shorelines and critical areas should remain the same.

Representative Debra Lekanoff (D-40, Whatcom, Skagit, and San Juan Counties) sees a failure in this standard. Actually, she sees the failure in everything happening around those shorelines and sloughs that are being kept at a status quo. “You see one line where the habitat just stays the same. You see another where salmon just goes straight down. Climate goes straight up. Unless we make the habitat line go up, the others will not change.” To make that habitat line go up, she has been championing a concept called Net Ecological Gain.

Generally, Net Ecological Gain would replace the old standard and require a development or plan to correct its impacts beyond a strict status quo. “Build buildings that reduce impacts,” Rep. Lekanoff says. “Instead of planting flowers, plant a habitat for the area. Invest in soft [shoreline] armor and green building.” In a descending list of preference, these mitigations could be: avoidance, minimization, rehabilitation or restoration, offset, and compensation.

In the 2020 legislative session, Rep. Lekanoff co-sponsored a bill to make Net Ecological Gain the legal standard for projects, policies, plans, and activities. The first draft of HB 2550 defined the standard and mitigation hierarchy. A substitute bill that narrowed the scope to simply study the issue was cheered by municipal organizations, but did not make it out of committee.

While the standards are debated, the data is not, partially because some is not there. Science is missing a lot of information from its understanding of the Salish Sea and its ecosystems. Adaptive, basin-wide data and science across Puget Sound requires the coordination between cities, counties, and tribes, a relationship that has been absent for the first three decades of the Growth Management Act.

To bridge this gap, proposed amendments for 2021 include improving relationships between the state and tribes. Tribal representatives have participated in the Road Map process to develop the amendments. A provision for “Participating Tribes” allows broader participation for the tribes to voluntarily take part in the county and multicounty planning process.

Rep. Lekanoff sees the net ecological gain in this cooperation, a picture where some of those trend lines get more attention. “With the tribes on customary areas, now the state has city data, state data, and collaboration with tribes. A holistic approach to monitor scientifically. This is what success looks like. It’s not going to happen in my generation. It’s going to be a generation from now. We see the light a little bit.”

Adaptive Planning

When asked what Washington looks like in five years if GMA amendments are successful, an urban planner like Yorik Stevens-Wajda suggests, “It would be cheating to say the world is a better place.”

Stevens-Wajda is the Legislative Chair for the Washington State chapter of the American Planning Association. Such a goal is cheating because “better place” needs some hard data. “Everything, and it’s a theme of planning lately, is a focus on implementation. There are many metrics that are not going the right way. Health, climate, economy, salmon runs. Many could be vastly improved. Quality of life in a dynamic urban-rural state may be harder to quantify. The rest can get better on the ground.”

Proposed GMA amendments look to broaden data collection and share it regionally. Integrating participating tribes into data collection will provide a more holistic picture of ecosystems. Safe Harbor provisions will offer local decision makers wide access to regional information.

Just collecting the data is not an endpoint. Crucially, the complete data must be used to answer the right questions and hold comprehensive plans to their goals. Is the data showing improvement where the plan projects improvement? Did it produce the outcomes expected?

What becomes more difficult is doing all that again and again, year after year. Too often, the plan itself is the end. “This plan will not sit on a shelf! It’s a focus on action!” Stevens-Wajda notes is a phrase that most planners have heard many times. (Occasionally from our own mouths.) But the promise hits the reality of time as “many of these comp plans have been going on autopilot.”

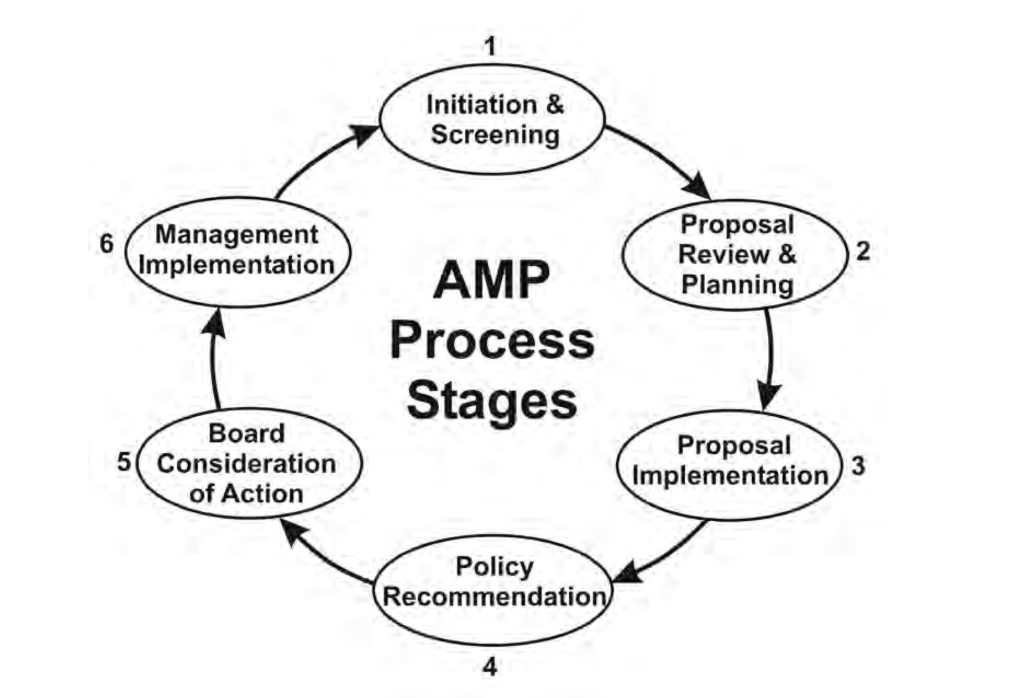

To move away from autopilot, comprehensive plans need to, well, perhaps be a little less comprehensive. With all that data coming in, cities need to monitor their plans, to figure out how well their plans are hitting projections and targets. But here’s the trick: we need to match the correct level of monitoring with the correct level of government to take on the issue. Enter adaptive planning.

Adaptive planning is restructuring aspects of growth management and implementation to the appropriate scales, then developing processes for monitoring and evaluation.

If you want to fix the watershed, you need to plan at the watershed scale, to implement at the watershed scale, and to monitor at the watershed scale. You can’t expect positive results when there’s twelve separate plans for different towns along a river, two counties collecting data, and no one doing implementation.

We can repeat this for all of the hard problems facing Washington today. Housing. Ecosystem restoration. Economic development. Transportation. None of our boundaries are the correct size. We need to find the correct level of governance to tackle these problems and plan from there. Adaptive planning is finding the right sized patch for the hole.

On the local level, adaptive planning means moving away from a one-size-fits-all model. For smaller or slower growing places, adaptive planning means added flexibility through voluntary participation and incentives replacing certain ironclad regulations. The comprehensive plans for these towns will sit on a shelf and collect dust if the town doesn’t have the authority to monitor and implement the programs. Adaptive planning is finding the right sized plan for the town.

In jurisdictions that adopt full comprehensive plans, adaptive planning means more responsibility in some places and more cooperation in others. Counties and larger cities will identify tasks and schedules in a work program to implement their comprehensive plans. Implementation will include benchmarks, indicator monitoring, and cooperation between jurisdictions. In doing so, the city and county may have to hand off some of its authority to a larger body that fits the problem. Adaptive planning is finding the right-sized region for the system that’s under duress.

Most interesting is the question of what happens when monitoring shows that indicators are not being met. The broader field of adaptive management is a “structured, iterative process of robust decision making in the face of uncertainty with an aim to reducing uncertainty over time via system monitoring.” It involves meeting objectives, accruing information, and improving future management. The concept has been used in wildlife management, international aid, and logistics.

The short answer is that we don’t know. Washington’s growth management does not iterate very well. Changing that may be the first test of this new approach. The GMA has waited 30 years for a comprehensive rewrite. Shortening the time for iterating the next round of changes would be a tremendous victory for adaptive planning. Just like the comprehensive plans written under it, the Growth Management Act should gather no dust.

Planning Dividend

To be honest, this last term does not appear in any of the proposed legislation or presentations. But the cost of putting together any plan looms like a guillotine over all parts of the GMA process in this tight budget year.

Washington has 281 municipalities, of which 126 have less than 10,000 people. These small municipalities range from the smallest, Kahlotus with 193 people, to Port Townsend with 9,831. Not all are vanity HOAs like Medina. Eighteen of these cities are county seats, representing just less than half of Washington’s counties. For small jurisdictions, paying a planning staff to develop a comprehensive plan with a long list of state-mandated requirements is impossible. For large jurisdictions, even with paid planning staff, the problem gets exponentially larger.

One of the biggest hurdles to implementation is “going to be the resources to do it,” says Stevens-Wajda. “Anything that adds a requirement would take time, resources, and create risk of appeal. Somebody’s got to write the plan, figure out what the plan will do to avoid unintended consequences, and someone is going to sue you.”

That last part may be partially alleviated by the Safe Harbors proposal, but the overall costs still remain.

Each county and municipality in Washington faces a budget shortfall similar to the State, without the same scale of revenue or taxing and bonding authority. In order to confront regional issues like housing or existential threats like climate change, pools of money larger than individual towns is necessary. As Tovar puts it, “These issues have never been more urgent and we’ve never been more constrained.”

When it was passed in 1990, the GMA was accompanied by $16 million in state aid to help jurisdictions come up to speed with the new law. Since that time, the funding has dwindled. There was an infusion of $5 million to plan for affordable housing in 2019 under HB 1923. Last year’s legislative session failed to fund Tovar’s work to convert the Road Map to legislation. The program relied on funding from an agency agreement between UW and the Department of Commerce as well as outside grants from American Planning Association and Amazon.

Every conversation about the GMA turns to the immense financial savings of smart planning. Updating the GMA now and funding localities to implement it will pay enormous dividends tomorrow. “To the extent there is the ability to devote resources to this work, it will produce positive outcomes and be worth it,” Stevens-Wajda said.

“You can plan for growth and plan for redevelopment,” says Commerce’s Anderson, “but that’s ultimately going to need infrastructure. Planning is a lot less expensive than concrete.”

An investment in planning comparable to the 1990’s $16 million would be $31 million today. To compare, Washington’s capital budget–which funds mostly concrete–is $8.8 billion for the 2019-2021 two year budget. The capital budget for environmental restoration efforts is $115 million. The budget for highway improvements is $2.9 billion. The total budget for Sea-Tac’s new International Arrivals Terminal is also approaching $1 billion. Compared to these capital costs, a $31 million investment in making sure they are being developed in the right places is almost a rounding error.

But planning is about avoiding error. It’s a planning dividend because properly funded, planning can avoid many of the costs of putting the wrong road in the wrong place. Rep. Lekanoff sees a dividend from the coordination between agencies. “When your conservation department walks across to the planner and says ‘you’re looking at zoning, this is what salmon looks like in that area. You’ve got billions, you don’t want to zone that way.’ Department of Ecology can walk to Commerce and sit down, before Washington state dumps $3 billion in culverts and puts in $4 billion in salmon recovery on top. Let’s do this right. That’s what this is about. How do we streamline in Washington state recognizing the investment?”

Tovar expands the planning dividend beyond concrete. “Pay to have this improvement process continue, or pay more expense in appeals and acrimony and not getting the results people want.”

And that is vital, because the planning dividend extends beyond mere construction. More than one discussion came around to the concept that housing policy is social justice policy is climate policy. As Rep. Fitzgibbon noted, GMA amendments closely tie to the House Democratic Caucus’ priorities of Covid relief, racial justice, budget, and climate. Tovar thinks GMA amendments will get traction in the session because “it’s all part of the recovery.”

Unfortunately, in this weird year, it’s not always clear which recovery we’re talking about. But let’s just appreciate for a moment that we are talking about the future. In this time of loss and division, Washington is in a position to look multiple steps ahead, past this recovery and into the next. While we chirp at the ways the GMA has fallen short, we can appreciate its incredible successes preserving land and prompting good planning. With some amendments to the GMA, we can get great planning in the future. Our ability to see there is a future comes from the solid work of the past.

Chalk up hope as a planning dividend too.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.