Last week, the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) released a report (PDF) laying out a framework to advance Cascadia’s high-speed rail hopes. “Rather than relying on congested highways or increasing air traffic, UHSGT [ultra-high-speed ground transportation] offers sustainable alternative to traveling greater distances quickly and reliably,” the executive summary states.

While a plan to design a plan isn’t exactly riveting stuff, the show of support from regional leaders was impressive, and it’s another hurdle cleared on the long path to high-speed rail.

“We are living in unprecedented times that call on us to envision our future in new ways. Transformative infrastructure projects like this one could help us rebuild our economy in the short term and provide us with a strong competitive advantage in the future,” Washington Governor Jay Inslee said. “Imagine fast, frequent and reliable travel with the potential for zero emissions and the opportunity to better compete in a global economy. It could transform the Pacific Northwest.”

Cascadia Rail, an advocacy group formed to promote high-speed rail in the corridor, was pleased with the news.

“The holidays came early this year with the delivery of the latest WSDOT report outlining actionable steps forward into making high-speed rail a reality in the Pacific Northwest,” said Paige Malott, Chair of Cascadia Rail. “We were delighted to see the values that Cascadia Rail has been championing on equity, meeting climate goals, and alternatives to air travel were included on the first page of the executive summary. Our region’s values of prioritizing equity and accessibility for all are highlighting this project as a national example for other high-speed rail systems in development around the country.

British Columbia Premier John Horgan said the report provided a path forward for collaboration.

“Improving connectivity in the Pacific Northwest region through ultra high-speed rail presents enormous potential for job and economic growth on both sides of the border,” Premier Horgan said. “This study provides a path forward for British Columbians and gives us a clearer vision of what can be achieved when we all work together.”

Oregon Governor Kate Brown emphasized the climate benefits.

“Bringing high-speed rail to the Pacific Northwest would bolster our economies while contributing to our efforts to combat climate change,” Governor Brown said. “This study affirms that a regional high-speed rail system would yield an equitable and modern transportation infrastructure that benefits people, the environment, and the economy. This type of bold investment would help position our region for the future.”

Microsoft president Brad Smith also contributed a quote for the executive summary and emphasized the time people would save.

“High-speed rail will shrink travel times throughout the Cascadia Corridor, providing a strong transportation core for our region,” Smith said. “This report provides a valuable roadmap for making this international project a reality.”

Malott suggested Microsoft’s leadership could inspire more businesses to pitch in: “Microsoft has been a visionary supporter since the beginning of this project, and we look forward to more business partners and community organizations getting involved and making Cascadia high-speed rail part of our ‘New Normal.'”

The recipe for high-speed rail

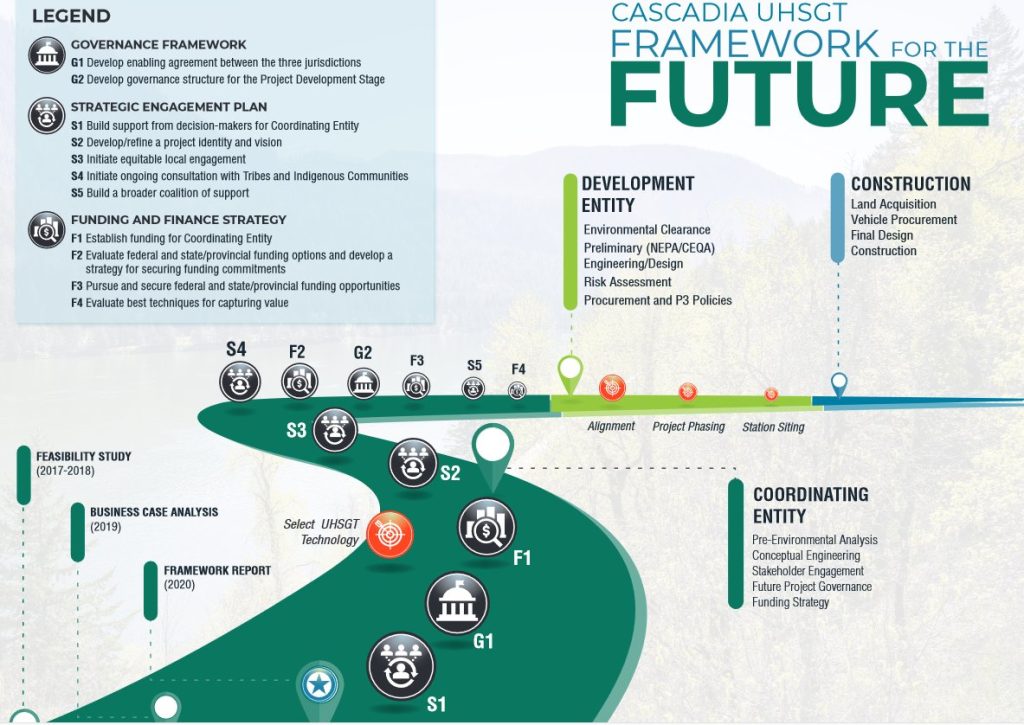

So what exactly is the roadmap to a plan? The report suggests the next big hurdle is setting up a coordinating entity to work across state and national lines and advance pre-environmental analysis, conceptual engineering, stakeholder engagement, future project governance, and funding strategy. The immediate next step is to “initiate equitable local engagement,” which may shows goals like reducing displacement of residents is important and lead to refining the scope to include social housing and upzones near the stations.

The vision from the Cascadia Innovation Corridor, a business-led advocacy group spearheaded by former Washington Governor Chris Gregoire, has been a little different; a recent “Cascadia Vision 2050” report claimed that hub cities of 300,000 residents or more in rural areas are the key to accommodating growth and maximizing high-speed rail’s effectiveness. We at The Urbanist are skeptical (here’s why) and would prefer to grow and invest in existing cities rather than pave over more farmland and forests.

The official study from WSDOT didn’t wade into that controversy and was much more focused on the nuts and bolts. Developing an enabling agreement between the three jurisdictions is one of the more immediate tasks. That enabling agreement will also need to come with funding to support the coordinating entity as it conducts all the needed stakeholder engagement and planning. Consulting tribal governments and indigenous communities is listed as a step, which is crucial since the line is likely to cross several reservations and may open up old wounds stemming from the first wave of intensive White colonization in the Northwest fueled by transcontinental railroad construction and the dubious land grabs and treaties signed and ignored along the way.

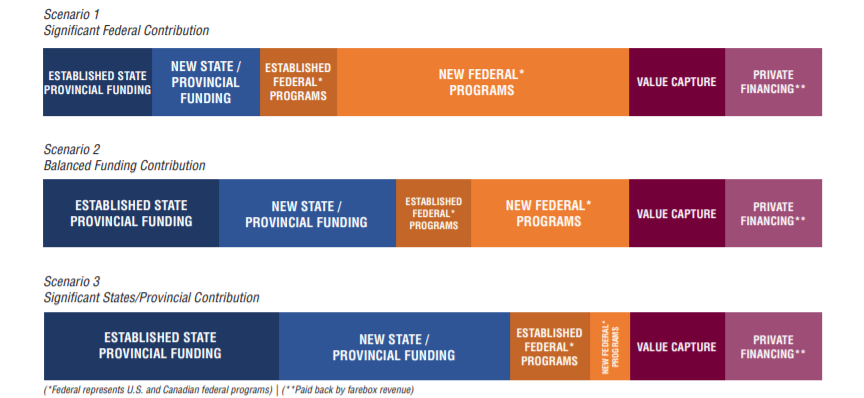

Each of the three state and provincial jurisdictions (plus Microsoft) has chipped in to conduct the planning so far, but the sums are sure to increase significantly as planning progresses, making federal matching funds more instrumental–and the report offers three funding scenarios with one even suggesting federal dollars could cover the majority of planning costs.

If the coordinating entity successfully navigates the planning process, it will then have to determine how to fund construction costs as it hands the project over to the development entity. Capital costs for high-speed rail from Portland to Vancouver, British Columbia is currently pegged at $24 billion to $42 billion, according to the feasibility study. Similarly, the report offers three scenarios, largely varying by how much federal match is included.

Federal funding opportunities, Green New Deal

The report offers some possible revenue options for each jurisdiction. For Washington, the report suggests a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system and/or regional property tax near station areas. For Oregon, cap-and-trade or regional property tax around station areas is proposed, and for British Columbia, a provincial appropriate, a motor fuels tax hike, or regional property tax near stations. The report also notes existing federal programs in both the United States and Canada that would fund a project like Cascadia high-speed rail.

A federal stimulus or Green New Deal climate packages could theoretically include high-speed rail funding, as well, which Cascadia Rail and The Urbanist have noted, flagging Rep. Seth Moulton’s (D-Massachusetts) bill dedicating $205 billion to high-speed rail. It’s hard to imagine that bill surviving Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and his exhaust-huffing Republican colleagues, which is yet another motivation to take back the senate–and the two runoffs in Georgia at least tie us up if Democratic candidates Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff prevail.

If high-end ridership forecasts come to pass, the feasibility study predicts the line will operate in the black, with revenue able to cover operating costs. But as 2020 has showed us, a lot can happen that disrupts forecasts. The enabling agreement will need to determine how to split operational costs or profits between the jurisdictions.

Learning from mistakes like Columbia River Crossing

WSDOT’s consultants, which include WSP and EnviroIssues, also provided an analysis of how large cross-jurisdictional projects like this get tripped up. Interestingly, the Columbia River Crossing I-5 expansion project (examined at Page 35 of the report) was one of the case studies, though the report had to tread lightly since it was a WSDOT report trying to note how WSDOT had botched a project while that same department is simultaneously trying to revive that project with minimal changes.

Thus, a misguided freeway expansion megaproject predicated on a number of road widening myths (including made-up traffic projections and climate denialism and greenwashing) gets diplomatically boiled down to WSDOT had a hard time “managing project identity over long periods of time and through uncertainty.” That said, there is truth in the observation that complicated megaprojects are inherently slower which means greater challenges for project managers in maintaining a narrative and weathering changing political moods. “After more than 15 years in the public’s imagination, and after multiple shifts in course, it became more difficult for the project to tell the full story, or to pivot communications without confronting its sprawling history,” the report notes of the Columbia River Crossing. The phrase “confronting its sprawling history” takes on many layers in an urbanist’s imagination.

In a weird twist of fate, it could be joining lots with the Cascadia high-speed rail project that could be what finally gets the Columbia River Crossing built since dual-use supporting high-speed rail could be a major selling point for the new bridge–originally envisioned as a highway sprawl project. But we have to make way for the future, whether the highway engineers are ready for it or not.

The other case study was the California High Speed Rail project, which faced significant setbacks. One takeaway from the analysis is California business leaders, particularly in Silicon Valley, have not been very supportive of the project, especially when it comes to financial assistance. Microsoft’s leadership hopefully means Cascadian business leaders will be more visionary and helpful. Another lesson was to integrate high-speed rail with local transit networks and provide immediate tangible benefits rather than California’s route, which (to be blunter than the report was) is to build really fast trains in the Central Valley without a workable plan to reach Los Angeles or the Bay Area yet in place.

What’s clear from the 77-page report is that much work remains just to get this project shovel-ready let alone build it, but at least there’s a recipe to do that work now.

An earlier version incorrectly identified Brad Smith as CEO rather than president of Microsoft.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.