These convenient excuses help your transportation department justify widening and adding highways–but they’re dead wrong.

We put our environmental values right into our name in the Evergreen State. But one place we don’t put them is into our transportation system – our state’s number one source of climate emissions. Even headed into third term of a governor who has cultivated a climate leader brand, our state’s emissions stubbornly keep climbing.

Over and over again, we open giant highway megaprojects like the SR-99 tunnel–or the decade spent on the almost not quite there Puget Sound Gateway–and Governor Jay Inslee and other Democratic leaders cut the ribbon and boast of its wonders. How do we square our highway widening obsession with our aspirations of climate leadership? We probably can’t, but maybe we have rationalized each step towards climate denialism for so long that we have started to believe our own lies? Those lies have gotten very complicated and yet routine and official-sounding.

Transportation agencies seeking to widen roads increasingly point to climate impact as a benefit rather than a drawback. If you have pushed back against a project on the basis that catering to single occupancy vehicles is driving carbon emissions–particularly in Seattle with our access to generally clean choices for electricity–you have probably heard a few of the following myths about road widening and how it is good for the climate and environment.

Myth 1: Car idling is bad for the environment so wider roads with free-flowing traffic is good for the environment.

Highway departments frequently claim congested roads and a lack of free flowing traffic leads to cars idling (cars stopped in traffic with the engine on) and thus more carbon emissions and pollution. Idling certainly does emit carbon (and other pollution) to little benefit, however it isn’t a good reason to widen roads or reduce time and opportunity to cross roads on foot at the dreaded “free flowing” intersection. The Department of Energy estimates that 2% of the emissions of a car come from idling as a nationwide average. This means that if Seattle were to eliminate all idling by making traffic free flowing, just a 2% increase in driving due to these newly unjammed streets would equal the CO2 emissions saved from idling.

In brief, induced demand – lower congestion leads to more people driving further (covered here, here, here, and here) – is likely to crush any benefits of reduced idling by increasing the number of miles driven by cars – and likely lead to the return of congestion and idling, now with more cars. While these road width machinations are bound to fail, newer cars already automatically shut off engines to avoid idling and electric cars emit nothing while waiting in traffic. This myth is also well debunked here by City Observatory.

Myth 2: Relieving congestion allows buses to travel faster–it is basically an investment in public transit which is good for the climate.

If you’ve ever asked the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) to remove a lane of general purpose traffic for a bike lane or wider sidewalk you have probably heard this one: “what about the buses?!” On one hand they are right, frequent rapid transit requires decongested travel lanes and leads to more people riding buses instead of driving cars which reduces CO2 emissions. Great! However, adding general purpose lanes where buses, freight, and personal vehicles mix doesn’t solve the problem. Similarly, repurposing general purpose lanes does not cause the problem.

Though widening lanes may provide momentary relief of congestion and help buses move through the city, these benefits are short-lived due to induced demand–a crucial concept to understanding why we can’t widen our way out of congestion, which is why we keep harping on it. Personal cars come back to impede each other and the buses. Rather than widening roads, dedicated space should be set aside for buses and their efficient use of space and low carbon emission per person transportation.

A textbook example of this mythical rationale can be seen in the lurking project to expand the Montlake Bridge. At four lanes wide on the current bridge, transportation and the environment would be better off making two of those lanes transit only instead of expanding the Montlake bridge to be four (wider) general purpose lanes and some window dressing.

Myth 3: More people moving to the city means more motorists needing to get around–hurry, widen the roads!

The idea that a growing population requires adding highway space sounds true, like commonsense even. But reality can be counterintuitive. Seattle is growing rapidly but traffic volumes are basically flat. Local traffic engineers ignore this fact and cleave to their unofficial professional oath to always predict ever-increasing traffic and plan ever-expanding roads. The recent Ballard Bridge study was an example of this. Despite Ballard having an exploding population and mostly static traffic counts, engineers keep predicting traffic armageddon. Widening road out of old habit and traffic engineer superstition is a poor excuse and a terrible vision for the future. A growing population does need more transportation, but it has to be space efficient and have a low environmental impact, such as public transportation, walking, and biking.

Myth 4: Once all cars are electric, road widening won’t be a climate issue anymore.

Electric cars aren’t coming fast enough, and in cities we have cheaper and better alternatives ready (or nearly ready) to go. In addition, electric cars still consume large amounts of resources (energy, batteries), wear out our public roads, and cause additional environmental damage (particulates from tires and brakes, which kill salmon). Though electric cars will reduce climate emissions of our personal vehicles, that benefit does not justify their priority in cities where there are alternative modes of transportation that are safer and leave more of our public space for the joy of people.

The research suggests electric cars emit half the carbon of their conventional combustion equivalent over their lifecycle, but other forms of pollution remain in similar quantities, such as the tire and brake particles linked to salmon kill offs. Electric vehicles do not solve the issues of geometry or safety. Electric cars still take a large amount of resources to create and are expensive beyond the means for many people. The adoption rate of electric cars (and possible plateaus) are not good enough for our climate goals. Changing to electric cars may be the best option for some, but for urban transportation there are many better options.

Myth 5: It’s a chicken or the egg dilemma, we can’t give up the car while everything is so car dependent.

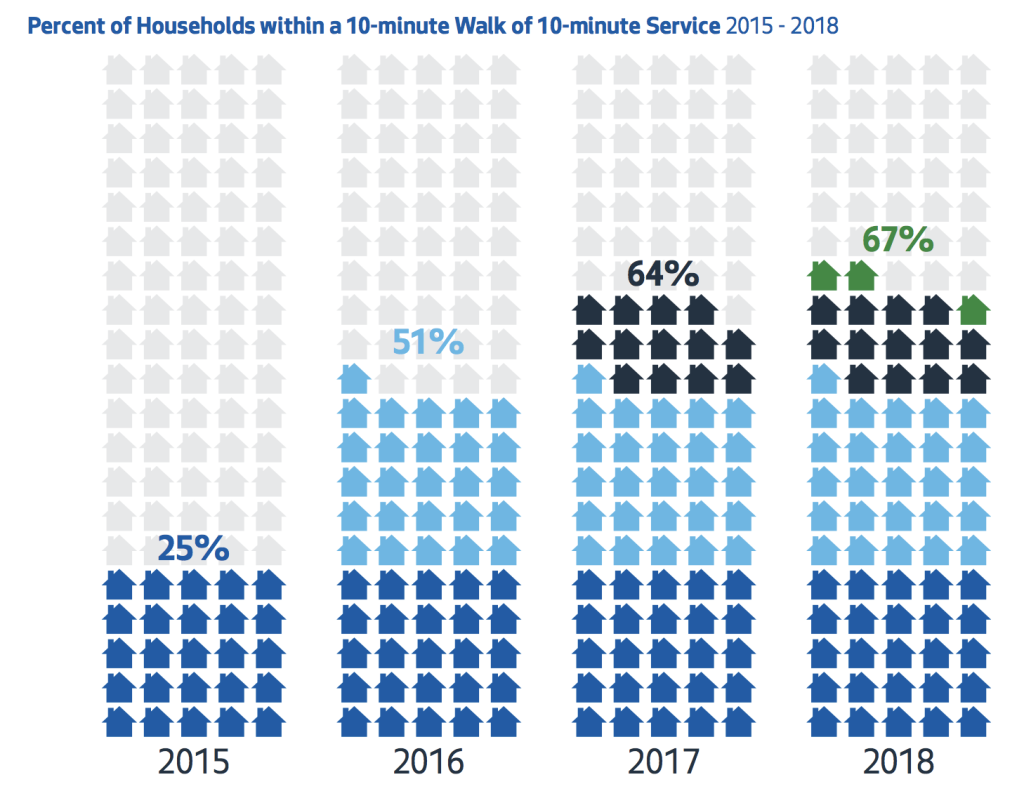

In some ways this is true; we have to be careful and work hard not to abandon people whose only means of accessing the benefits of Seattle are by car. But investing in highway widening crowds out investments in transit, walking, and biking and delays the transition. While some people will claim their city’s transit and walkability must be as good as London’s or Tokyo’s before they can turn away from cars. The perfect can be the enemy of the good, and Seattle’s transit is pretty good. By 2019, 70% of Seattle’s population lived within a 10 minute walk of frequent transit. We’re already a national leader in forming car-free households.

Examples from aboard show that car-dependent cities had to take the leap and once they did amazing transformations were possible. Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, and so on used to be largely overrun with cars, but they invested in biking infrastructure and prioritized transit and became synonymous with walkability, bikeability, transit excellence, and climate leadership. This can be our path too, but we have to choose it. We can’t wait for it to magically manifest.