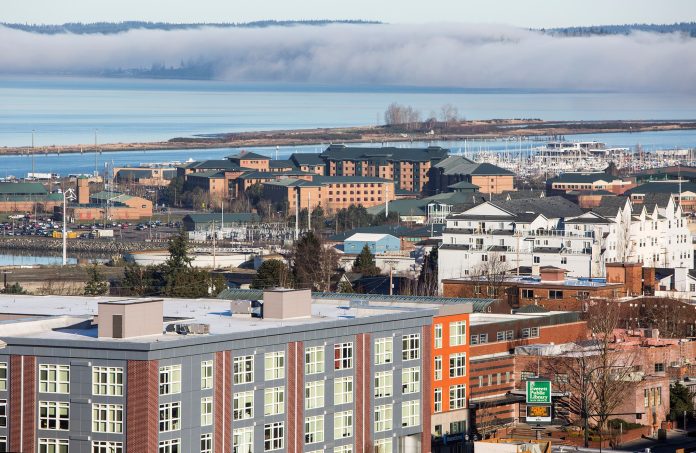

In early November, the Everett City Council adopted sweeping zoning and development regulation changes to simplify the land use code and encourage more urban infill development. The zoning and development regulations came about as part of the city’s “Rethinking Zoning” initiative, which will be followed up by a more in-depth “Rethink Housing Action Plan Process” to develop solutions that could deliver more affordable housing in the city. This all comes on the heels of Metro Everett, which led to significant downtown zoning changes adopted in late 2018. That zoning process incorporated many form-based zoning principles into the land use code and permitted more highrise development in the city center, topping out at 25 stories.

The city’s zoning and development codes have long been a hodgepodge spread across various titles of the municipal code and 56 separate chapters. The “Rethinking Zoning” changes adopted fully consolidated regulations in one title with 35 separate chapters under the banner of the “Unified Development Code” similar to Snohomish County. Many of the chapters simply were ported over to the Unified Development Code title, but there were some deep amendments made in some to consolidate zoning and reform development standards.

Through the update process, Everett was careful in how Metro Everett was dealt with. The adopted legislation does technically repeal the Metro Everett provisions, but has essentially reincorporated them into the new chapters of the land use code mostly as they were. This was done through consolidated zoning and applying a citywide approach to height limits, uses, bulk regulations, urban design standards, and street improvement standards.

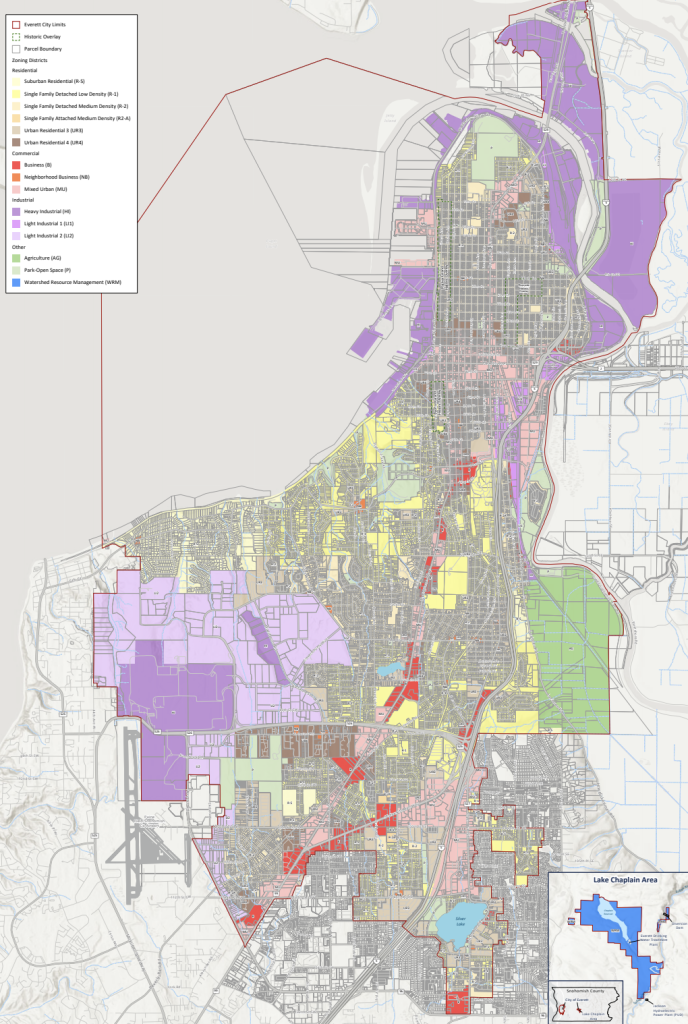

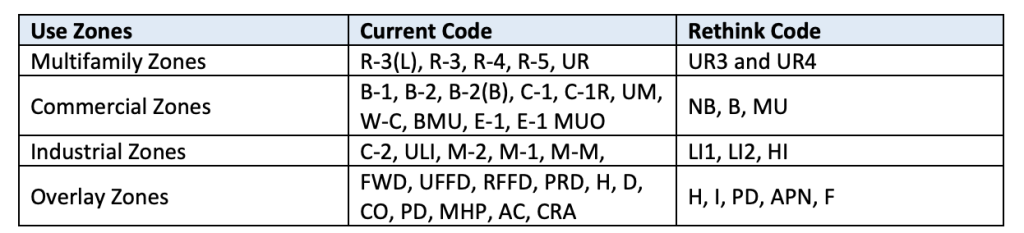

Chief among the zoning changes are consolidations of multifamily, commercial, industrial, and overlay zones. The number of zoning districts was trimmed from 25 to 15. Overlay zones were also reduced from 11 to just five. Single-family zones were the only zoning classifications to escape changes for now, which include Suburban Residential (R-S), Single Family Detached Low Density (R-1), Single Family Detached Medium Density (R-2), and Single Family Detached Medium Density (R2-A) zones, though an earlier concept had envisioned trimming single-family zones down to two with more flexibility. By category, zoning districts were collapsed into the following:

- Six multifamily zoning districts became just two as as Urban Residential 3 (UR3) and Urban Residential 4 (UR4) zones;

- Eleven commercial zoning districts became only three as Neighborhood Business (NB), Business (B), and Mixed Urban (MU); and

- Five industrial zoning districts became either Heavy Industrial (HI), Light Industrial 1 (LI1), or Light Industrial 2 (LI2).

Everett also reformed open space and critical environments into three zoning districts, namely the Agriculture (AG), Park-Open Space (P), and Watershed Resource Management (WRM) zones.

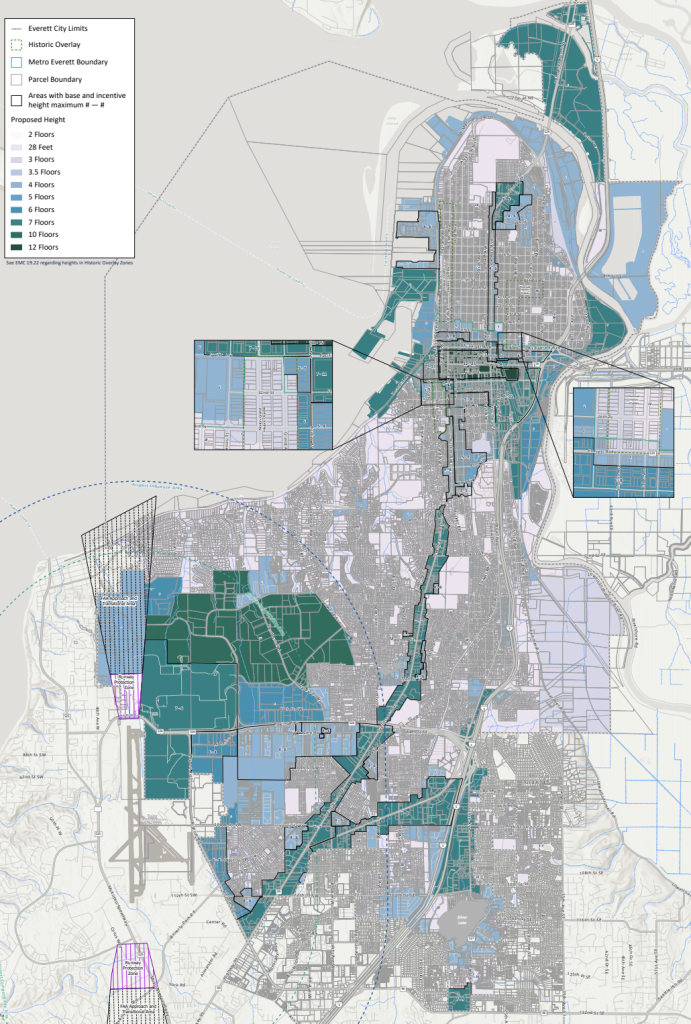

To retain unique bulk attributes that many of the zones contained, Everett adopted a height map that overlays zoning districts and new general height standards. This largely retains the status quo with regard to height limits that were in place, but there were some cases where things went up or down. Building height measured in floors is 15 feet for the first floor and 10 feet for each floor above, meaning that a lot limited to three stories would be limited to 35 feet in height. However, single-family zones are strictly limited to 28 feet in height and UR3 zones are still limited to a maximum of 50 feet in height.

The adopted legislation builds upon Metro Everett which used this overall height limit approach. In some cases, development on properties with higher intensity multifamily and commercial zoning or a TOD street designation will need to meet minimum height limits to avoid underbuilding. New transition standards were also implemented when taller development is adjacent to residential zones, decreasing the height limits at the border.

Other notable changes that the legislation made, include:

- Simplifying uses by combining the general use table (160 recognized uses) and Metro Everett use table (70 recognized uses) into one use table with 83 listed uses. This also involved the creation of corresponding definitions for each use since not every use had a definition previously.

- Streamlining other bulk standards (i.e., setbacks, lot coverage, and density) by using simplified tables. There were changes that lifted density caps in some zones, introduced density minimums to prevent underbuilding, and allowed setback averaging exceptions to provide flexibility.

- Expanding the street designation approach to regulate street improvements, building form, and street-level uses that Metro Everett introduced. This was introduced to areas outside of the city center to reach Broadway, Rucker Avenue and Evergreen Way, Everett Mall Way, 19th Street SE, and areas zoned NB and with CO overlays. Application of these standards on the new streets could result in wider and more sidewalks, greater overhead weather protection, restrictions on street-level uses, and building transparency requirements.

- Triggering street improvements at three dwelling units instead of five dwelling units and sidewalk improvements at one dwelling if located in a sidewalk priority area (i.e., Metro Everett or within a quarter mile of a frequent transit corridor, major arterial, public school, or public park).

- Consolidating building form and design standards for development in zones and other cases where it is required into three streamlined chapters for residential uses (e.g., single-family detached, townhouses, cottages, and accessory dwelling units), multifamily development, and non-residential development.

- Allowing one accessory dwelling unit (ADU) to be paired with each duplex, triplex, and townhome in addition to a single-family home, increasing the allowed size of ADUs from 800 square feet to 1,000 square feet with some conditions, adding additional height flexibility, and eliminating ADU parking requirements when located within a quarter mile of a transit stop.

- Eliminating parking requirements for some housing for seniors or people with disabilities when located near frequent transit.

- Expanding the environmental review (SEPA or State Environmental Policy Act) categorical exemption of up to 200 dwelling units of residential development to all UR4 and MU zones.

To facilitate these zoning changes, Everett also adopted a slate of updates to the Comprehensive Plan. These largely involved acknowledging the new zoning names and consolidated zoning types as well as better defining the purpose of zoning districts. The adopted Comprehensive Plan update also made a spate of changes to the city zoning map and Future Land Use Map for consistency.

Last month, Mayor Cassie Franklin announced that Everett would begin a multiyear process to “Rethink Housing“. The process will look at how the city will be able to deliver affordable and no-income housing across the income spectrum for residents through a housing action plan.

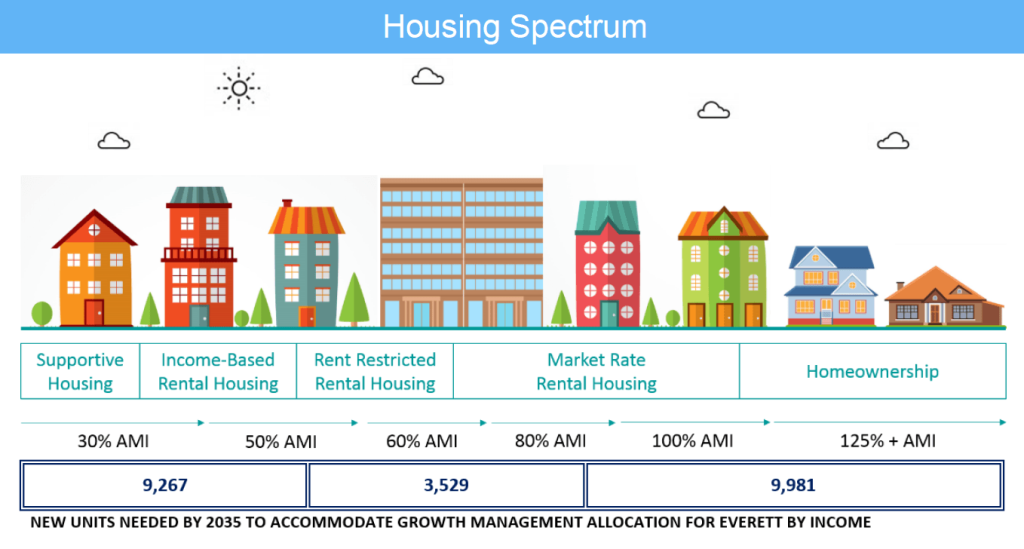

Everett estimates that about 9,267 housing units will need to come online in the next 15 years to serve people in the supportive housing and income-based rental housing band, which is generally below 50% of the area median income (AMI). Another 3,529 housing units will need to be created that serve people in rent-restricted housing and market-rate rental housing bands below 80% AMI. Beyond that, Everett thinks that 9,981 housing units will be needed for people with higher incomes looking for homeownership and market-rate rental housing. In all, that’s 22,777 homes over 15 years–a 1,519 per year pace.

In her directive, Mayor Franklin outlined progress that the city has made in addressing housing needs. “Since 2018, we have made meaningful progress in our efforts to encourage building capacity,” she wrote. “We have implemented actions such as adopting the Metro Everett Plan that increases residential densities in the downtown core and adjacent areas, expanded the Multi-Family Tax Exemption to other areas of the city, adopted reduced residential parking standards and adopted a special connection charge exemption for affordable housing.”

However, Everett continues to suffer like much of the region in making housing affordable and access to people. “…[L]ocal incomes are increasingly out of step with the cost of housing. In 2019, the median house purchase price in Everett was $389,000,” she noted. “Rental prices increased by 53% between 2010 to 2018. The median household income in Everett is only $55,000. Owning a home in Everett is out of reach for too many of our residents and even renting a home is challenging. Many households are one paycheck away from housing instability.”

She also explained at length that homelessness was especially acute in Everett due to a lack of resources and expressed a need for additional shelter and permanently supportive housing. Last year, low-income housing opponents waged a campaign that succeeded in blocking a Housing Hope supportive housing project, arguing such projects shouldn’t go in single-family zones or near them.

Her directive comes with three specific initiatives. The first deals with a public engagement process and development of a housing action plan by the end of June. The second calls for improving the city’s procedures and permitting processes around development. This specifically involves preparing for transit-oriented development and light rail that includes higher densities and mixed-income housing as well as encouraging more affordable and market-rate housing developers through reformed housing policies and incentives. The third directs the city to develop recommendations and solve student homelessness, pilot a shelter program with the state using Pallet shelters, allocate emergency federal funding for rental assistance and housing stability, and hire additional social workers.

In the coming month, the city will be hosting several events to engage in the process and help residents learn about housing challenges. The most concrete and long-lasting actions of the process though will probably be the recommendations derived from the housing action plan that the city will be able to pursue and further reforming procedures and processes around development.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.