There are probably a few King County Councilmembers kicking themselves right now for not running a countywide transit measure year. Seattle’s overwhelming 80.32% victory on Proposition 1 results suggests the city could have carried the vote for the entire county if that had been the proposition.

You can’t really blame them. The world was going to hell in a handbasket in March when King County voted to shelve the countywide measure as Covid’s first wave ripped through the country.

The pandemic is raging even worse now–though in a hopeful sign President-elect Joe Biden announced plans for a nationwide mask mandate to tamp down on the spread of the virus. Facing recession and another year of sickness and death, Seattle voted to stand by essential workers who rely on transit and make up one in three riders keeping society running so more fortunate folks can stay home. The revelation that people can be selfless and good is nourishing in cynical times when our ability to stand together rather than turn apart seemed in doubt.

Seattle’s vote will help slow the rate of bus service cuts in the region, but without action by the King County Council’s deeper cuts will be on the way. They will hit transit-dependent families hard. Investing now would be a show of solidarity. It’s the right thing to do, and it seems likely to pass.

Doubters will point to the failure of the 2014 countywide transit measure, but support for transit has grown since then. Running the measure in March was likely a drag on the 2014 measure. We can craft a better package now and run it in November when turnout is higher.

Crafting a package

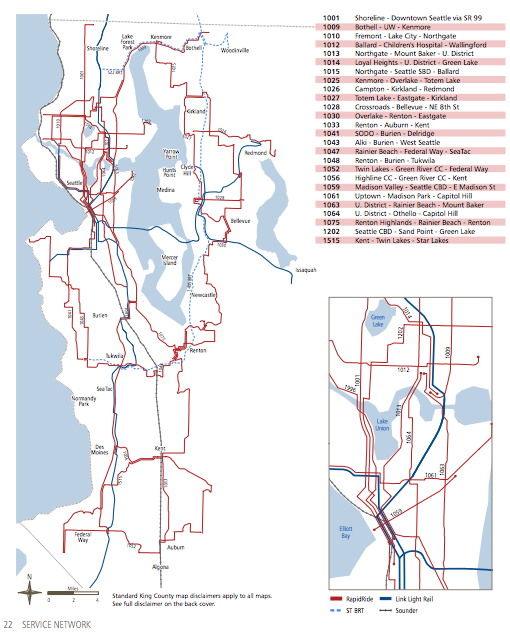

In 2017, Metro laid out a long-term “Metro Connects” vision planning transit investments to take the network to 26 RapidRide lines spanning the county and full electrification of the fleet by 2040, which also means remodeling and adding new bus bases, which is a major investment as well. The County estimated implementing plan would increase half-mile access to frequent transit by 60%, taking the share to 73% countywide–plus, the rate would be even higher in minority and low-income areas, which would reach 77% and 87% respectively. This would be a huge step to take, and a fitting commitment to county’s low-income residents and communities of color who have borne the brunt of the pandemic as essential workers on the frontlines.

Best to get busy building if we plan to achieve those visions, but unfortunately the agency latest actions have centered on scaling back the vision rather than realizing it. A recent update proposes cutting the pace of expansion in half, noting the need for a dedicated funding source.

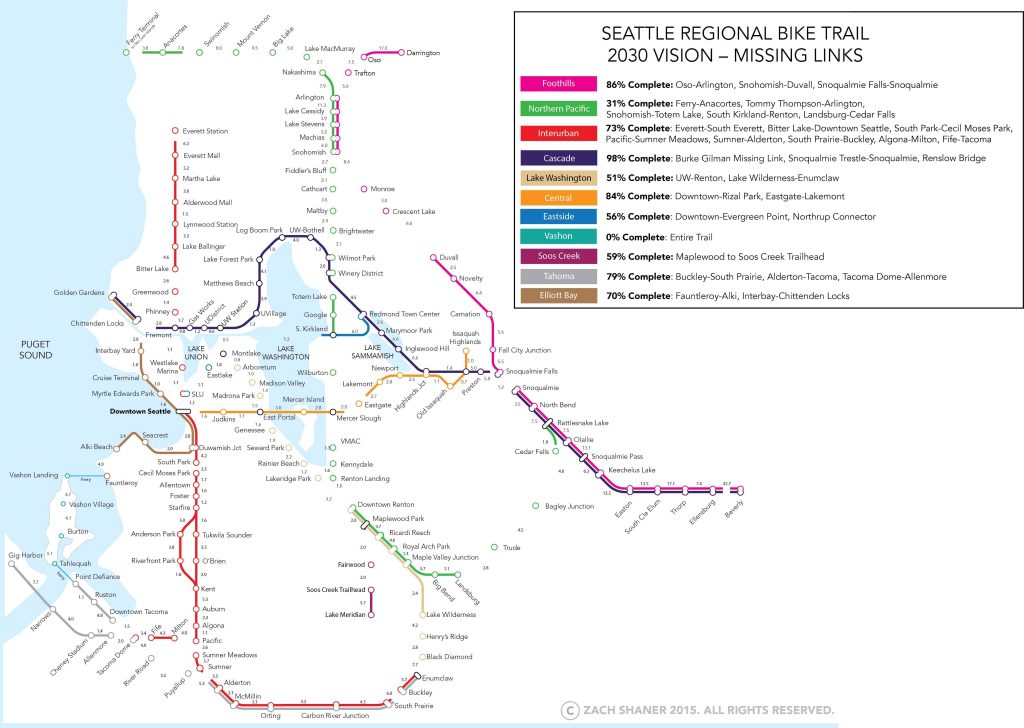

A county transit funding package should be on our near horizon, but we don’t need to limit it to transit alone. Another exciting result at the ballot this year was in Austin, Texas where voters approved both a major light rail and rapid bus package (including a tunnel downtown) and another $460 million measure investing in the protected bike network, pedestrian and trail improvements, and road safety interventions citywide. Austin pledged to finish 70% of its bike master plan for an on-street all ages and abilities bike network with $40 million from the measure, another $80 million is set aside for trails, and $65 million for Vision Zero safety upgrades. King County has some nice trails intermittently, but it lacks a cohesive network like Austin has planned.

King County Metro and the Seattle Department of Transportation should consider station access and street safety improvements as part of RapidRide upgrades, and that could be a way to allocate those investments. That said, a few marquee investments in the county trail networks could increase the measure’s benefit and buoy its prospects with voters.

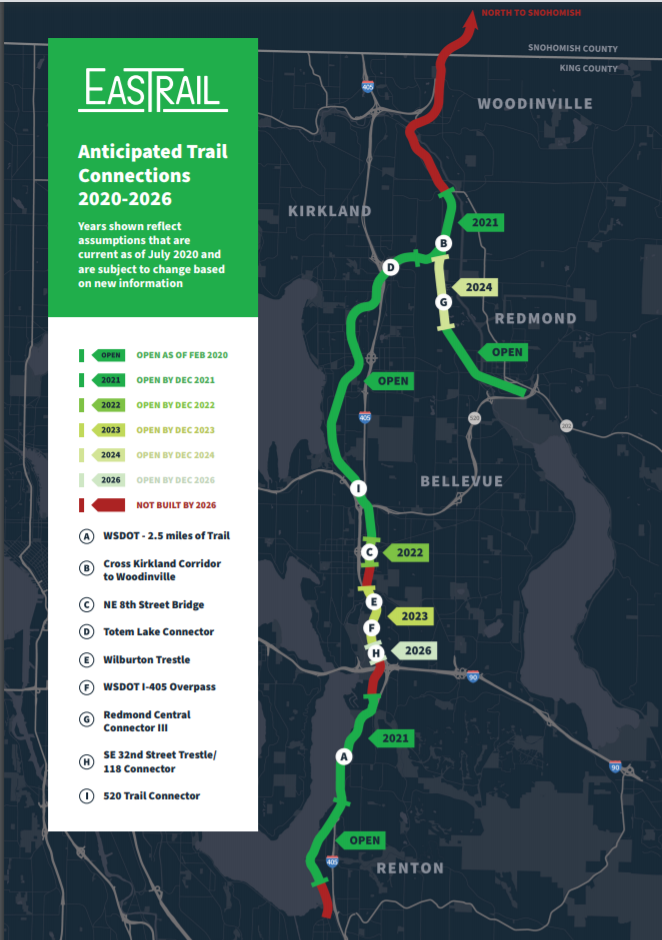

Southeast King County could use more trail connections and Shoreline is seeking a Trail Along The Rail tracking planned light rail opening in 2024, but will need funding to realize that vision. Another opportunity is closing the remaining gaps in the Eastrail Trail, a multi-use trail which would connect Renton to Woodinville via Bellevue and Kirkland by 2026, save for a few gaps.

The King County mobility measure could extend the Eastrail Trail northward and close the gaps in Bellevue and Renton. Improving and widening the Burke-Gilman Trail, Chief Sealth Trail, Interurban Trail, and turning Lake Washington Boulevard into a proper bike/pedestrian corridor could be some enticements on the Seattle side of the lake.

How much would it cost?

That leads to the question of how big the measure would need to be to fund all this. It’s somewhat scalable depending how many RapidRides we want to add, how much bus base work is needed, and how heavily to invest in trails and Vision Zero. RapidRide A through F Lines are in operation. Seattle’s Move Seattle Levy, though it promised seven RapidRides, appears set to build three. The County has salvaged RapidRide I Line from more ambitious earlier plans, and a Kirkland-to-Bellevue RapidRide K Line has been shelved. That means 10 RapidRides are already operating or funded.

Filling out the alphabet to 26 would take 16 more lines. Assuming a rough average of $50 million per RapidRide (which would leverage another $50 million in federal grants and perhaps more local match) would cost roughly $800 million. Accelerating electric bus base plans and doing some trail improvements would likely cost another few hundred million. So we’re looking at a billion-dollar package, at least, spread out over the length of the measure. With King County’s population of 2.26 million shouldering that load seems feasible, especially considering that Austin’s population of just shy of a million is investing a lot more than that in its bus, bike, pedestrian, and street safety network.

If a countywide transportation benefit district is the mechanism, then sales tax or flat vehicle license fees are the currently allowed funding sources. The County could lobby the state legislature to add more funding sources, such as a corporate payroll tax or income tax, or make the vehicle license fee more progressive by pegging it to vehicle value (like Sound Transit’s Motor Vehicle Excise Tax does). Another option would be run the measure as a levy relying on property taxes (with a low-income homeowner rebate).

We are at a tipping point where either we manage the decline of the county’s ambitious transit and climate plans or we invest and rebuild our momentum. On Friday, King County Executive Dow Constantine announced a $100 million low-interest loan to the Washington State Convention Center in order to continue construction on its $1.9 billion expansion on the site of a former county-owned bus station. If we have billions for a convention center, we should be able to fund transportation and climate action via an electrification and rapidification plan for our bus network. It’s just a matter of making it a priority.

Update: Did a little math and if Seattle passes a measure with 80.3% of the vote like it did with Proposition 1 in 2020, that measure would need only 34% in the rest of King County to pass countywide. This assumes Seattle accounts for about 36% of the county’s vote total, as it did this year, which might slip a bit. Regardless, it’s clear there’s a path to a countywide measure if the campaign is as strong as Prop 1’s was.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.