Abolishing apartment bans is how we grow as a region, not sprouting entire new cities in pasture.

The Cascadia Vision 2050 report made it onto KUOW with its claim that four cities of 300,000 to 400,000 residents need to be built from scratch in the I-5 corridor running from British Columbia to Oregon in order to accommodate growth.

Natalie Bicknell covered the “hub cities” idea in depth in an October article. There are pros and cons, obviously, but it seems more clear the study is being used to justify a fatalistic attitude toward reforming zoning in the Seattle region, rather than an idea really centered around environmental sustainability as billed.

“Unless existing cities like Seattle are willing to bulldoze 40% of their single-family homes, those cities won’t grow dense enough to fit all the people coming to the area in the next few decades,” KUOW’s Joshua McNichols said. “Because of this, housing will get more expensive, urban sprawl will increase and emissions will rise, the report says.”

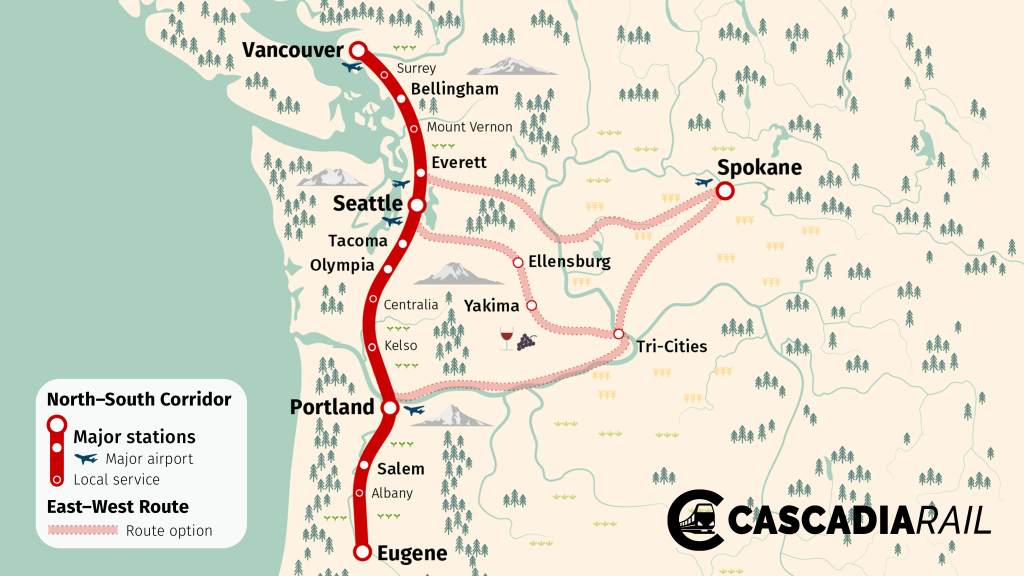

The Cascadia Vision report comes from Cascadia Innovation Corridor, a partnership between the Business Council of British Columbia and Challenge Seattle, which is led by Christine Gregoire, former Washington Governor, and brings together the region corporate moguls to try to solve problems and influence long-term planning. While the partnership made its name pushing for high-speed rail from Vancouver to Portland–which is a goal The Urbanist shares–they may be tackling the wrong problem with their hub cities plan. In contrast, Shaun Scott’s op-ed today in Crosscut laid bare that ending apartment bans is the fight, not simply to meet ambitious growth projections but to create more equitable, less segregated communities everywhere.

Ending apartment bans

The “bulldozing single-family homes” language from the report invokes the imagery of housing opponents and is misleading and inflammatory. For one, converting oneplexes (detached single-family homes) to fourplexes would not necessarily require demolitions. Accessory dwelling units (ADU) offer a way to add density without teardowns. Seattle, Tacoma, Burien, Olympia, and several other cities already laws permitting and promoting ADU conversion.

Moreover, the 40% figure sounds dramatic but over 30 years that only requires about 1.2% of single family homes to be converted to fourplexes per year. And we do not need to assume only fourplexes can be built in their place, we could allow more options than that and create something akin to the Forest City example the report cites in existing cities. Some neighborhoods are already seeing teardown rates exceeding that rate, and unfortunately too often these teardowns are leading to bigger, posher homes rather than more homes. Changing our housing rules can make the construction we’re already seeing anyway more equitable by encouraging more affordable options.

We can also promote more sustainable buildings. Washington state recently increased its height limit for mass timber towers to 18 stories. Now we just need the proper zoning to allow mass timber towers to go up in more places–and incentives and public investment to jumpstart the industry. Rather than grafting cities onto rural areas, we can build mass timber eco-districts in existing cities and generate a sustainable forestry employment boom in rural communities so they can grow in a more natural way.

Oregon recently legalized duplexes in cities statewide, and Portland made waves by legalizing fourplexes everywhere housing is allowed. Instead of arguing Washington and British Columbia should follow Portland’s lead and go further, Gregoire and friends are throwing up their hands their hands and proposing development in rural or exurban areas.

Chris Gregoire’s highway-building track record

The help Gregoire is offering the high-speed rail effort is commendable, but her track record on climate and transportation isn’t great. As Governor, she went all in on the SR-99 viaduct replacement tunnel (with a surface highway to boot) and steamrolled Seattle’s efforts to block the megaproject. This expansion of highway infrastructure in Downtown Seattle wasn’t just ungodly expensive and maligned with overruns and delays, it also blocked the alternative vision Cary Moon presented of transit upgrades and safer infrastructure for people walking, rolling, and biking. Governor Gregoire also pumped billions into highway building statewide, while underinvesting in transit.

So what are we to make of Gregoire and Challenge Seattle presenting themselves as sustainability gurus and urban visionaries? They may mean well, but it’s not clear they get it, as their push for routing high-speed rail to Bellevue rather than Seattle illustrates. The growth machine that Gregoire embodies can help us, but we need to harness it for maximum benefit rather than getting roped into dubious projects that distract from core goals around equitable development, urgent climate action, and preserving ecosystems and wilderness spaces. Megaprojects might provide lucrative contracts and windfalls to the developers, bankers, investors, and real estate CEOs that compose Challenge Seattle, but we have to be sure we’re picking the right projects and the public benefit is there.

The Cascadia Vision report said “hub cities” should be built 40 miles outside exiting urban areas “to keep land costs down,” without specifying where. That condition is probably too restricting to work, unless we aren’t counting places like Olympia and Bellingham as urban areas. Either way, there are only so many places that fit the bill, and since most of the relatively undeveloped spaces between Portland and Vancouver, B.C., is in Washington that’s where they are. Places like Mount Vernon, Burlington, Centralia, and Kelso have been thrown around as hub city sites, but it’s not clear development there will be that much easier than in cities, since people already live there and may fight for their “neighborhood character” and against change just as some Seattleites do.

Mount Vernon Mayor Jill Boudreau was a panelist at 2019 Cascadia Conference , where distributing growth along the planned high-speed rail corridor was a theme. Mayor Boudreau said her community could take growth while still maintaining a high quality of life, but that was before the unveiling of the hub city idea targeting upwards of 400,000 residents. Roughly halfway between Vancouver and Seattle, Mount Vernon has a population of about 35,000 (and 12 square miles) and would be about a half hour away from either metropolis with high-speed rail.

Where would hub cities even go?

Even if land costs are low, it’s going to be expensive to build a city from scratch. Sewers, roads, hospitals, municipal courts, schools, libraries, water, and garbage facilities: none of that is cheap to build, even if the land is. Plus a city of 400,000 even at twice the density of Seattle would consume 22 square miles. Achieving that density (18,000 residents per square mile) would require mostly avoiding detached single family home development, which consumes the majority of land in virtually every Cascadian city as it stands. And even achieving that, it’s not clear there’s one site with 22 square miles of undeveloped buildable land ready for taking, let alone four such sites.

In a way, the proposal is a return to the railroad landgrab days of our past, which brought cities like Tacoma into existence for Northern Pacific to exploit and turn into a company town. This helped railroad magnates recoup their expenses and turn a healthy profit building transcontinental railroads, but it didn’t make for healthy, equitable cities. I wonder if we’re repeating our mistakes here?

Cascadia should build a high-speed rail line and tons of housing near the stations. Rather than putting hub cities out into hayfields, we should reform our zoning and invest in sustainable social housing in existing cities. Cities like Tacoma, Everett, Bellingham, Olympia, and Seattle deserve that investment and they already make sense as high-speed rail stops. Rather than look outward for solutions, let’s look inward and upward.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.