Earlier this month, Ray Dubicki laid out why the Ballard Interbay Regional Transportation Study (BIRT) and its accompanying Ballard Bridge Replacement Study are failures. If you missed it, I recommend giving it a full read, but in short: the new plans are the same as the old plans, outdated and ill-equipped for the challenges that are coming to an area incredibly diverse in land use, with light rail on the way.

Not only is the siloed approach to multimodal planning completely faulty, but the actual data that guides the conclusions reached in the studies is bunk, a relic of an era that Seattle should have left behind long ago–one that assumes more car traffic in the future on city streets as a given.

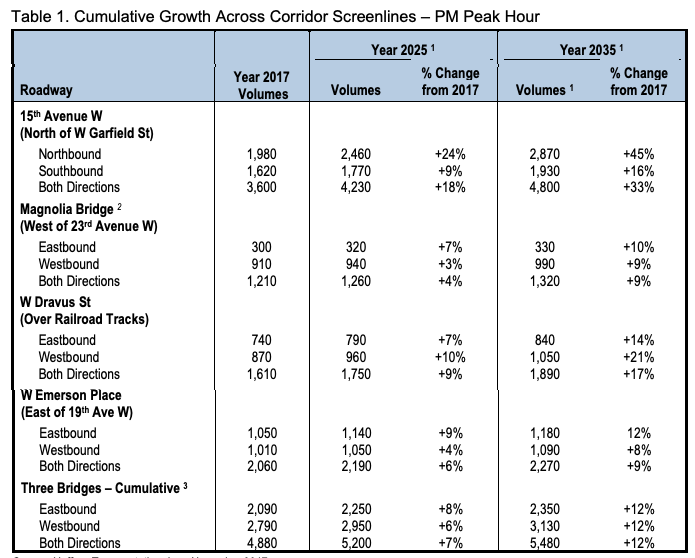

We saw this coming with the release of the Magnolia Bridge Study last year. In that study, the Magnolia Bridge itself was only forecasted to see modest increases in vehicle traffic by 2035, but every single nearby project that could impact traffic was combined together to spell out an increase of 33% in the number of vehicles using 15th Avenue W at Garfield Street by 2035. That had the tidy effect of making the in-kind replacement of the Magnolia bridge perform better than all of the other studied options, which all depended on traffic utilizing some stretch of 15th Avenue.

A 33% increase in evening peak hour travel, including a 45% increase in northbound traffic headed to Ballard, is not rational. Therefore all of the outcomes from the study on the replacement for the Magnolia Bridge are sitting on shaky ground from the outset. And now this year, we have the counterpart study for the Ballard Bridge’s replacement.

There, the traffic volumes being used to justify all of the alternatives are on even shakier ground than the ones further south for the Magnolia bridge. Whereas the Magnolia one used units of new housing being developed in Queen Anne, Belltown, and, yes, Ballard to come up with a percentage, the Ballard Bridge study doesn’t even bother to do that.

No, instead it assumes that the current Ballard Bridge will completely fill to capacity, and works backward from there. From the study:

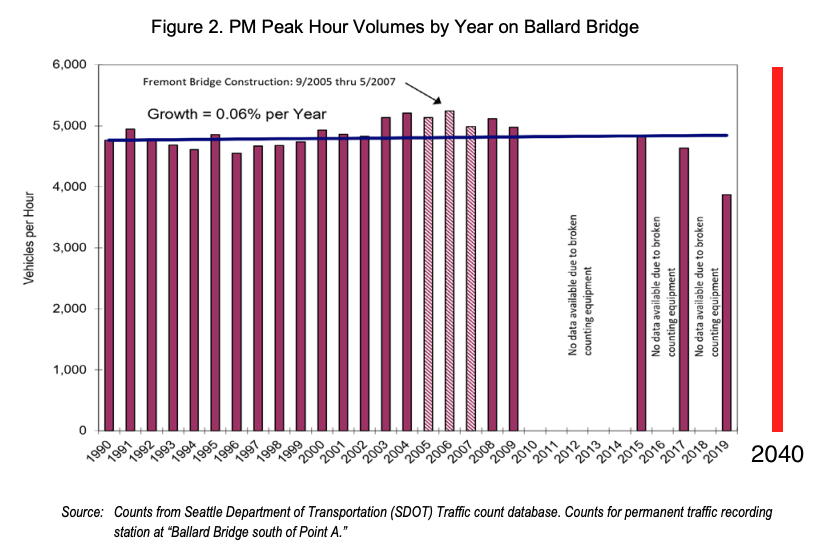

Year 2040 traffic volumes for the No Build (No Improvement) condition were estimated based on the capacity of the Ballard Bridge, which is estimated to be 2,800 vehicles per direction at the posted travel speed. Future volumes could exceed the capacity with crunch flow at a volume-to-capacity (v/c) ratio of about 1.2, which is a peak-direction volume of about 3,360 per hour. For the PM peak hour, the growth in northbound traffic from the existing 2,620 vehicles per hour to 3,360 vehicles per hour would reflect a compound growth rate of 1.2% per year, higher than the historic growth rate described previously, which has been less than 0.1% per year. Reverse direction traffic was also assumed to increase by 1.2% per year, which would reflect a traffic volume of 2,580 in the PM peak hour’s southbound direction.

In other words, the Ballard Bridge study assumes that by 2040, 5,940 vehicles per hour during the evening rush hour will use the bridge. Yet data going back thirty years shows that the Ballard Bridge has never carried that many cars–not even getting close to that number when the Fremont Bridge was under construction and traffic was diverting from the east. It assumes traffic volumes will grow twenty times faster than they have been growing.

We can add that forecast onto the historical data showing afternoon peak hour volumes to see how absurd it is:

Projecting growth like this for the Ballard Bridge goes against all available evidence. Between 1995 and 2019, the Ballard urban village added 5,665 housing units, an increase of 93%, to say nothing of the houses added in Greenwood-Phinney Ridge, Crown Hill, Fremont and other urban villages in North Seattle where residents would be likely to use the Ballard bridge. The amount of afternoon traffic on the Ballard bridge has gone up less than one tenth of one percent every year, 0.06%. At NW Market Street and 15th Avenue NW, the vehicle-centered heart of Ballard, traffic volumes were nearly identical in 1998 and in 2019.

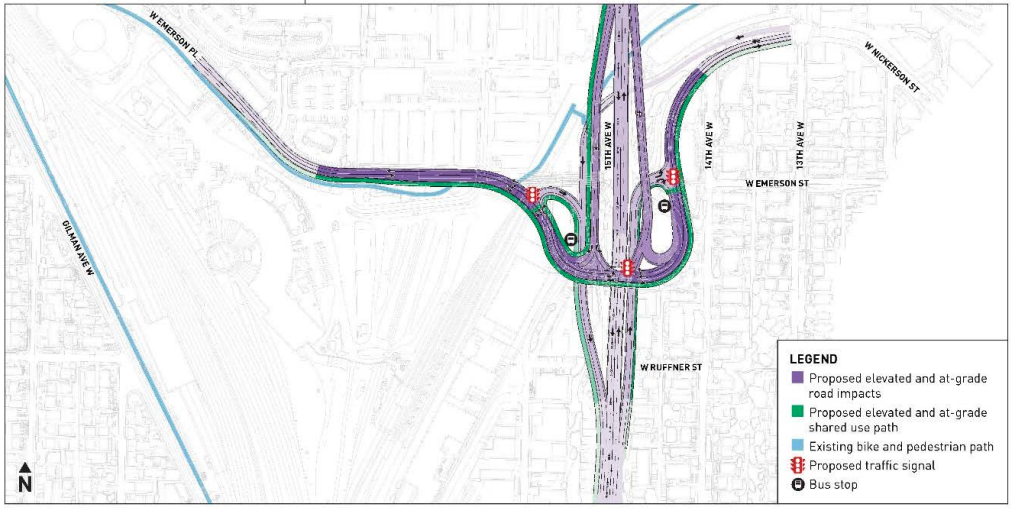

In Magnolia, the unrealistic traffic forecasts merely serve to prop up the option of replacing the existing bridge. In Ballard, the impact is worse, with the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) being pushed to construct new highway style infrastructure with the Ballard Bridge’s replacement. The three options moving forward for that replacement all include a design for a Modified Single Point Urban Interchange (SPUI) on the south end of the bridge at Emerson Street. This cloverleaf-style interchange, shown below, would ensure that the maximum number of vehicles can access the bridge, essentially ensuring that the traffic volumes that have no historic precedent will come to pass.

How was the Modified SPUI arrived at as the only acceptable option? Because of those same traffic forecasts. A normal signalized intersection, a regular traffic light, was considered but “even with dual left-turn lanes and right turn lanes on all approaches and multiple through lanes, the intersection would operate at a very poor level of service (average vehicles delay in excess of 160 seconds, and a northbound queue that could exceed 1,700 feet on average).”

This interchange wouldn’t be very far from Sound Transit’s proposed Interbay station, impacting the walkshed and making station access harder, all because of a traffic forecast that assumes a shift to transit usage and telework won’t continue.

The lack of sensible traffic volumes in these bridge replacement studies shouldn’t go unnoticed, and we need to ensure that decisions that could impact Seattle residents for generations aren’t based on them.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.