The three councilmembers say their plan investing $7.2 million annually will focus on “bridges with high-frequency public transit,” but they haven’t released the details.

A new bridge maintenance bill surfaced last night via a 8:43pm press release. Sponsored by Transportation Chair Alex Pedersen and Seattle City Council colleagues Lisa Herbold and Andrew Lewis, the proposal would impose a $20 annual car tab fee and dedicate the $7.2 million in expected annual revenue to bridge maintenance.

If the plan is enacted, Seattle car tab fees will go from $80 to $40 next year due to the expiration of the $60 car tab fees that had funded bus service via the Seattle Transportation Benefit District (STBD) measure 2014. The uncertainty around Tim Eyman’s Initiative 976 convinced the City to nix car tabs as a funding source for Seattle Proposition 1, which passed in an 80% landslide and renewed the STBD with a slightly larger 0.15% sales tax. Due to the loss of the $60 car tabs, the new STBD will still raise less revenue than the one it replaces.

The trio of councilmembers behind the bridge maintenance proposal cautioned against increasing the size of the STBD sales tax and opposed Councilmember Tammy Morales’ proposal for a 0.2% sales tax. Pedersen also voted against the compromise amendment raising the sales tax to 0.15%. While the bridge trio was tentative about raising revenue for bus service, they are gung-ho to raise fees to pay for bridge maintenance.

A tiny band-aid on a huge maintenance backlog

“Underfunding our bridge infrastructure increases the risk of harm and ends up costing taxpayers more later, so let’s listen to the independent audit and increase bridge maintenance now to keep our people and economy moving,” Pedersen said in a statement.

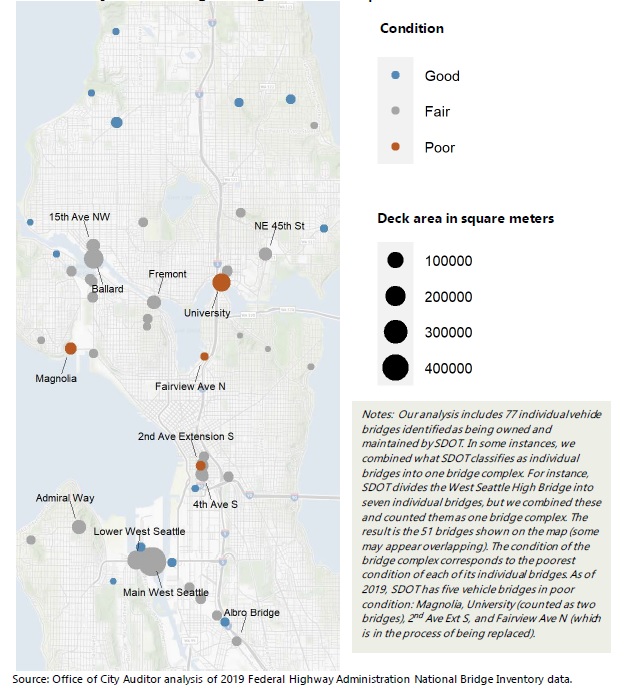

Both the press release and Pedersen’s blogpost stressed that the bridge maintenance backlog is quite large. The $7.2 million proposal would only raise a fifth of even the low-end estimate for annual need according to the Auditor’s report.

“The Seattle City Auditor recently published a report on the city’s bridges indicating high unmet needs for bridge maintenance. The engineering standard for bridge maintenance in Seattle ranges from $34 million to $102 million per year, and yet the current level for is only $10 million approximately. The city needs to add $24 million at the very least to meet the lowest estimate of maintenance needs.”

The revenue stream is also far too small to tackle enormous investments like replacing the Magnolia Bridge, Ballard Bridge, and the ailing West Seattle Bridge, which will likely be repaired for now to reopen it to traffic sooner and avoid the bigger investment immediately. Councilmember Lewis campaigned on a 1:1 full replacement for the Magnolia Bridge despite low traffic volumes that indicate the bridge is overbuilt as is.

While the sudden emergency closure of the West Seattle Bridge has brought bridge maintenance into the forefront of policy discussions, SDOT has said it wasn’t deferred maintenance that did in the 36-year-old bridge. More likely it was a construction defect that the 2001 Nisqually earthquake exacerbated. Ramping up maintenance is unlikely to have prevented the failure of Pier 18 and the cracking that forced emergency repairs. Although Pedersen has acknowledged this, he argues the West Seattle Bridge closure is still a wake-up call to get serious about bridge maintenance citywide.

While Lewis, Herbold, and Pedersen see big needs in their districts, bridges are not distributed evenly throughout the city and council districts. Council District 2, 3, and 5–Councilmembers Morales, Kshama Sawant, and Debora Juarez’s districts, respectively–see fewer bridges and a less pressing maintenance backlog. Council will have to grapple with how passing a measure that will invest little if anything in those less-bridge heavy districts squares with geographic and racial equity and our moral and legal commitments to the disabled community. Anna Zivarts, director of the Disability Mobility Initiative at Disability Rights Washington, questioned the bridge proposal in Heidi Groover’s story in the Seattle Times.

“We’re in the middle of a pandemic and devastating recession. Is bridge maintenance the best transportation investment in this moment? Or should we be directing this revenue towards transportation investments that more directly address the needs of the people most impacted?” Zivarts said.

Climate implications

The Urbanist has called on leaders to have a reckoning with the climate impact of our transportation system and sprawling land use patterns. We’ve urged the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) to downsize its car bridges so it can focus investments on climate-friendly priorities, lower vehicle miles traveled, and lessen its staggering maintenance backlog in the future. The bridge maintenance plan seems to sidestep that conversations. Earlier this year, Councilmember Pedersen sponsored legislation that requires a climate note for new bills, but it’s not clear that requirement will force that conversation in this case–and Ace Houston argues climate notes will fail to generate climate action in general.

Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda said the proposal seemed car-centric during a council session. Pedersen countered that buses and people biking and walking rely on bridges, too. The “direct the additional funding to bridges with high-frequency public transit” line in the press release seemed a rebuttal attempt to that criticism. But without details on the plan let alone what definition of high-frequency they’re using, it’s not clear which bridges would qualify and be targeted. Pedersen’s recent post included pictures of the Ballard Bridge, University Bridge, Magnolia Bridge, and West Seattle Bridge, if that’s any indication.

Some of the highest profile bridges carry high-frequency transit but may not in the future. For example, once West Seattle Link and Ballard Link open, the West Seattle Bridge and Ballard Bridge may carry far fewer buses, with service truncated to the new light rail stations. Does investing in these bridges count as transit investments? And should we using precious STBD funds for other priorities–like the transit it was originally intended for?

How much will $7.2 million help when the backlog is so much larger than that? I’d argue that Councilmembers should be planning a measure to completely fund maintenance rather than a package too small even to be a half-measure. And rather than adding a climate note to justify the decisions we were already likely to make, Seattle needs a compressive climate strategy that gets our transportation system on a carbon-neutral path and reforms our land use to encourage walking, biking, and affordable urban housing.

The Urbanist has advocated for increasing car tab fees to slowly restore the funding source, thereby erasing Tim Eyman’s heist. This $20 car tab proposal gets the first part right even if the spending plan isn’t ideal. Cars should pay the maintenance costs and social costs they cause. The problem is that Seattle only gets one bite at the apple for the next two years since state law requires a two-year cooling off period before raising car tabs another $20 with councilmanic powers (e.g., not going directly to voters). And councilmanic car tab fees have a hard cap of $50 car tabs without voter approval, so this revenue-gathering technique will eventually be depleted.

It appears likely that the bridge funding measure will pass since the three sponsors must only find two more votes to constitute a majority. Hopefully, in the process we have the bigger conversations, too, rather than patting ourselves on the back for a band-aid that is a largely symbolic given the scale of maintenance backlog and diverts funding from bus service.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.