SDOT’s new BIRT and Ballard Bridge studies continue history of mistreating the industrial neighborhood.

Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) released two studies last week. Both looking at infrastructure in Ballard and Interbay, the studies lay out a blueprint for spending billions of dollars in transportation money. They are both categorical failures.

The narrower study specifically looks at replacing the Ballard Bridge. This is a necessary first step to improving a vital link in the city’s transportation system. Unfortunately, the study makes a series of half-baked assessments that total up to several very wrong alternatives.

The broader study is the Ballard Interbay Regional Transportation Study (BIRT), a state-initiated look at the many transportation projects going on in the Ballard-Interbay corridor. However, the end result is not broad at all, but a rewarmed plate of soggy old plans.

The studies represent many things that are wrong with modern urban planning. They are traffic study pseudoscience wrapped in a thin gauze of social justice, like stuffing styrofoam into a reusable bag. In the few times one of the studies picks up a complex issue, they find the way to develop the most regressive answer possible, usually adding more asphalt. The rest of the time, they kick hard questions down the line or just deny they are part of the study to begin with.

The city and state legislators receiving these studies must immediately dismiss them. It would not serve any purpose to drop them in the trash. Instead, these studies should be taught in basic government classes as examples of how we got here. Worse than being fraudulent, the BIRT and Ballard Bridge studies illustrate how well-intended bureaucracy allows neighborhoods to remain detached, polluted, and segregated.

Let’s Review (very briefly)

The Urbanist has given me the opportunity to write about Interbay and industrial Ballard a few times. The upshot is that we have a rare piece of real estate that most people don’t give a second thought. Interbay is the intersection of the Ballard Locks, the fresh water Ship Canal, the salt water Elliott Bay, and the massive BNSF rail yard. The corners are filled in with industrial land where modern tech offices raise the rent for legacy fishing fleets. Wrapped around that are a dozen automobile bridges, an urban highway, bike trails, and three of the wealthiest neighborhoods on the West Coast.

That urban highway prevents most people from thinking about the neighborhood they’re passing through. Elliott Avenue W turning into 15th Avenue W is six lanes of speedway that lets Magnolians peel off to Magnolia, Ballardites rush to Ballard, and Queen Annians ignore the other two. In the meantime, 30,000 people work in Interbay and industrial Ballard, many still going to their essential jobs in a pandemic from homes out in suburbs they can afford.

A high-speed zip through Interbay also lets us forget that all these bridges and infrastructure are crumbling. With decades of wear since they were built or last upgraded, Magnolia Bridge, Ballard Bridge, Emerson St., Nickerson St. and many others are in poor condition, nowhere near ready for an earthquake or climate change. The city planning in the area is just as antiquated, with a 22-year-old zombie plan setting the rules for zoning and dozens of other plans and studies nibbling at small topics with no real lasting impact.

Into this maelstrom steps the Ballard Bridge and BIRT studies.

The Studies

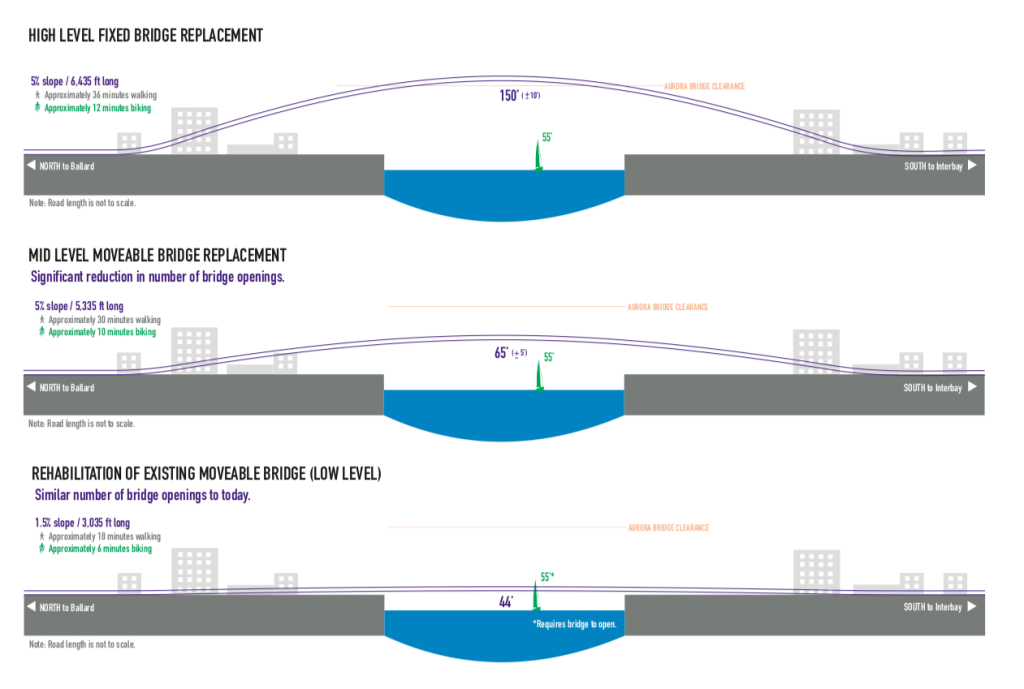

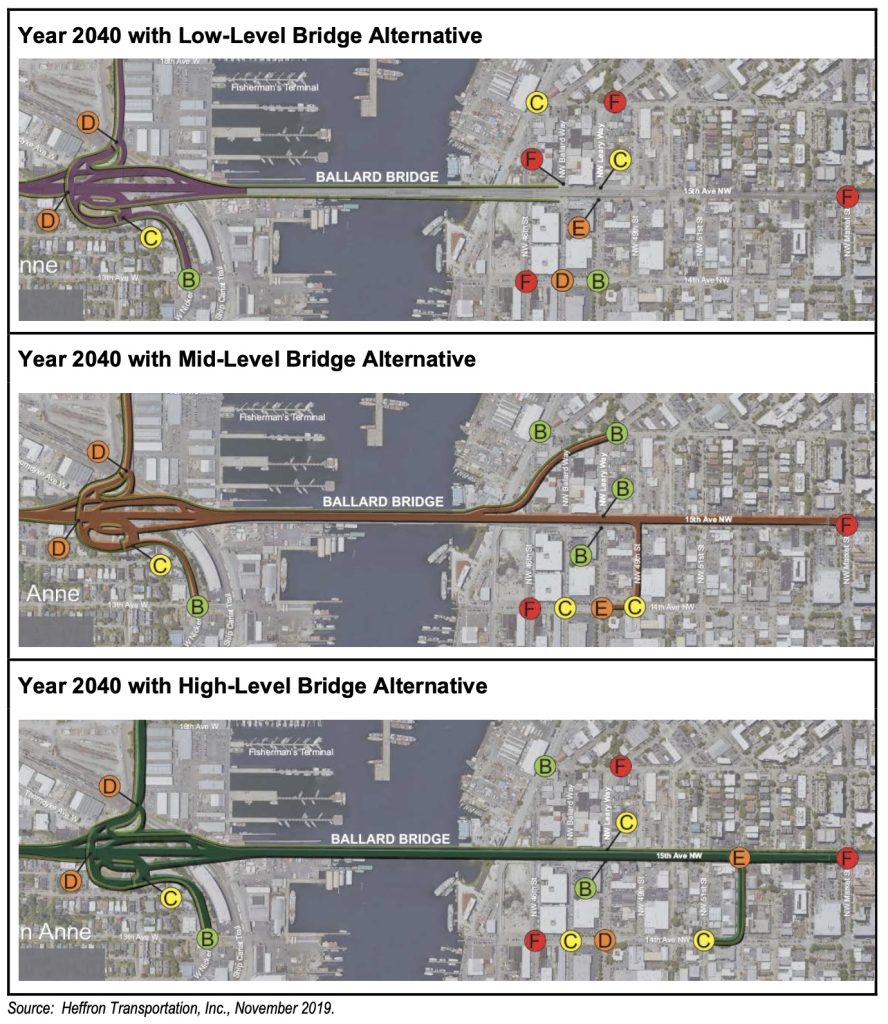

The Ballard Bridge Study consists of an executive summary and a few appendices supporting the three “options” that were laid out by SDOT in the summer of 2019. SDOT proposes to replace the Ballard Bridge with:

- Drawbridge the same height, constructed identical to the existing bridge and with the same number of openings to allow ships to pass.

- Drawbridge a little higher, with a closed height 20’ higher than the current bridge. This would allow most smaller boats to pass and reduce the number of openings.

- Fixed bridge a lot higher. This would be tall enough to eliminate the need for a drawbridge, about the height of Aurora.

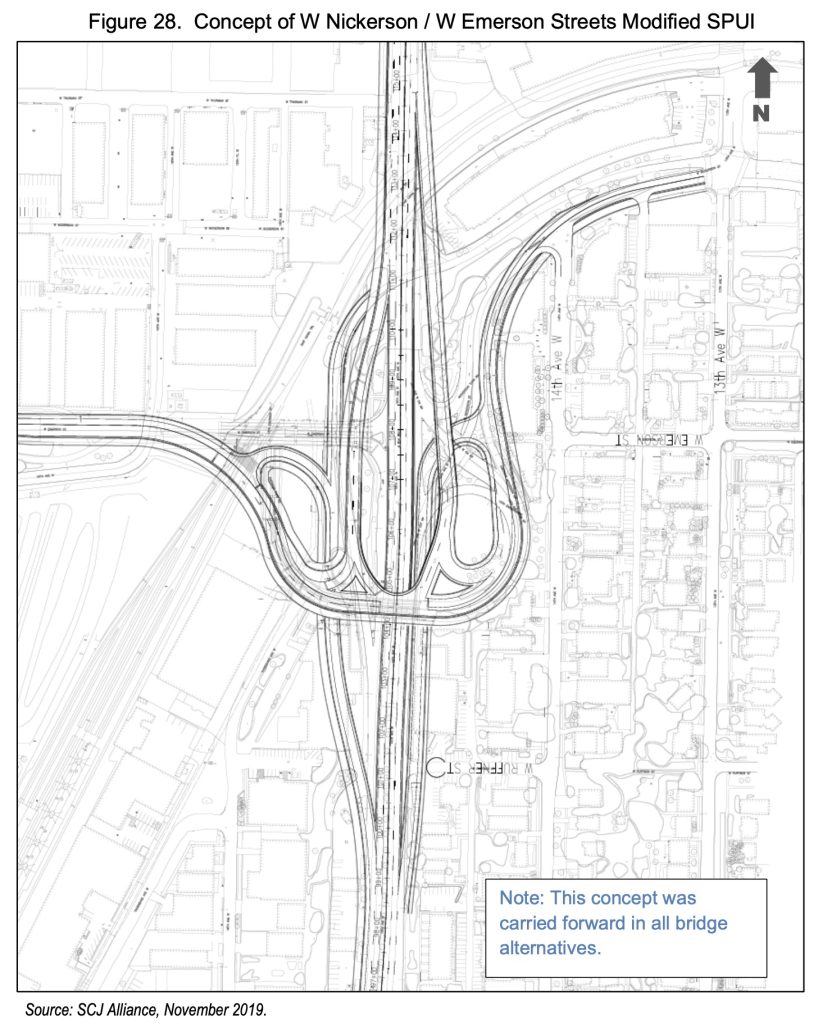

Raising the bridge deck would reduce or eliminate the number of openings of the drawbridge, but would also make the bridge 2,000-3,000 feet longer. The study proposes to reconstruct the Emerson and Nickerson interchange in all three variants, with no change of location. The extra length of a higher bridge would be pushed north into Ballard. Preserving an intersection with Leary requires extensive ramps in the two higher variants.

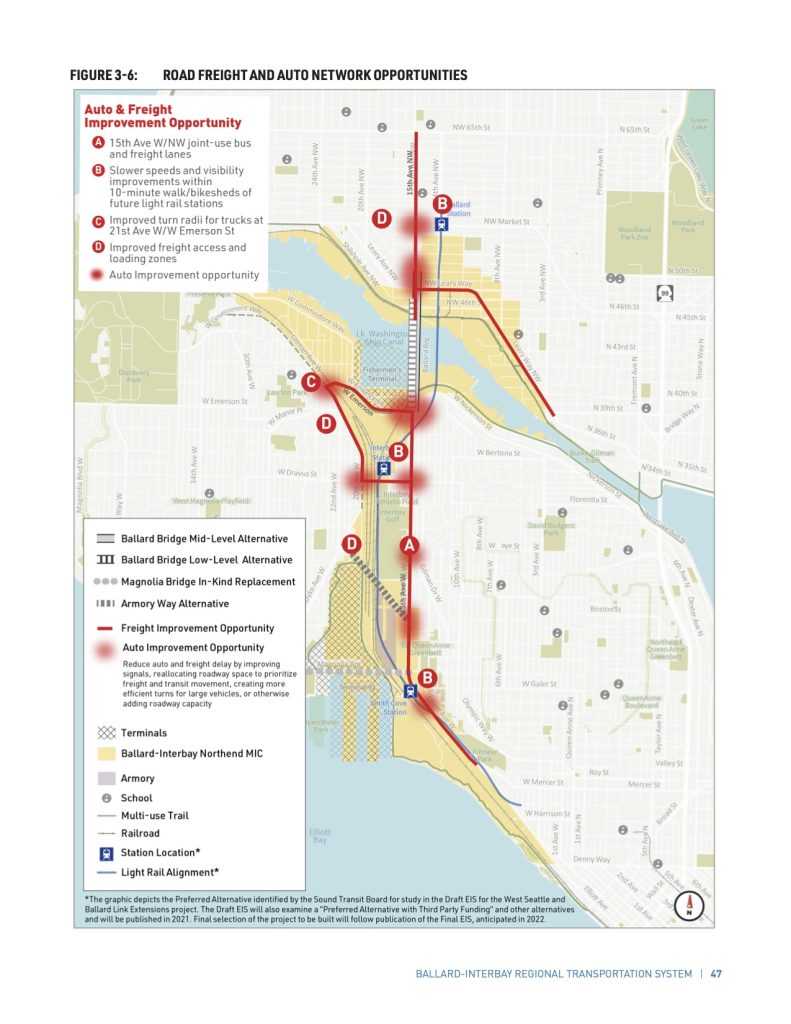

Feeding into the Ballard Bridge is the larger Ballard Interbay Regional Transportation network, looked at in the BIRT Study. Established by an act of the Washington State Legislature, the BIRT study took 11 months to review existing plans, forecast multimodal integration, analyze impacts and benefits of new bridges for Ballard and Magnolia, and develop a timeline and funding strategy for replacing infrastructure.

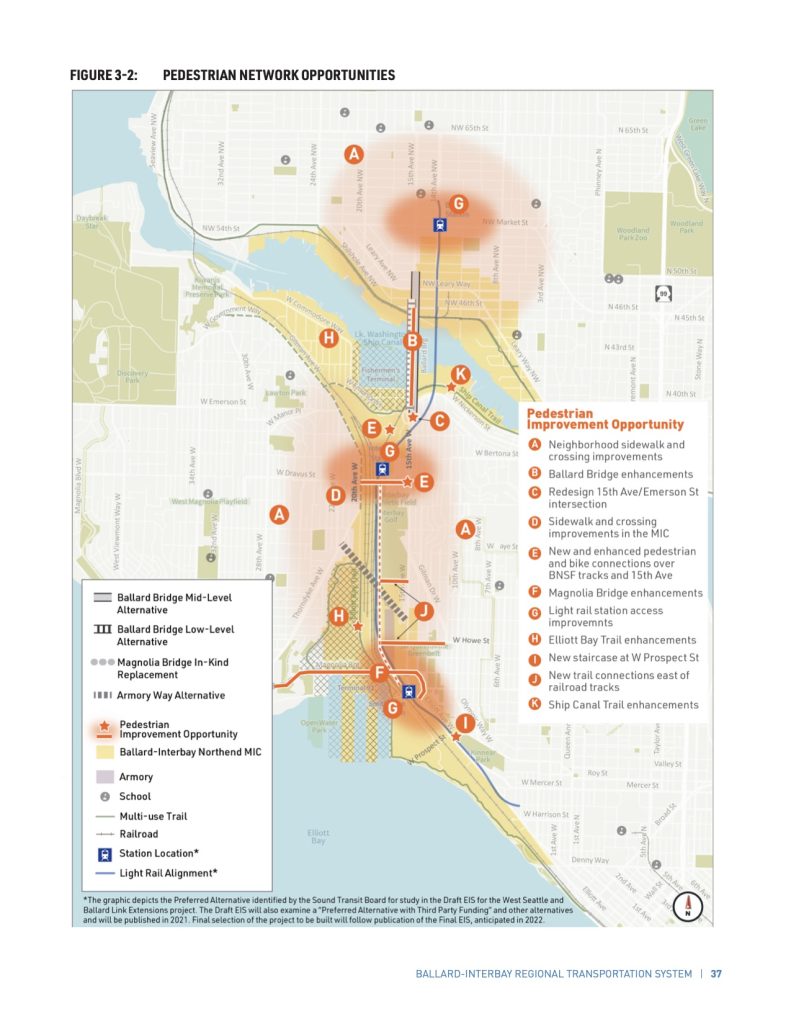

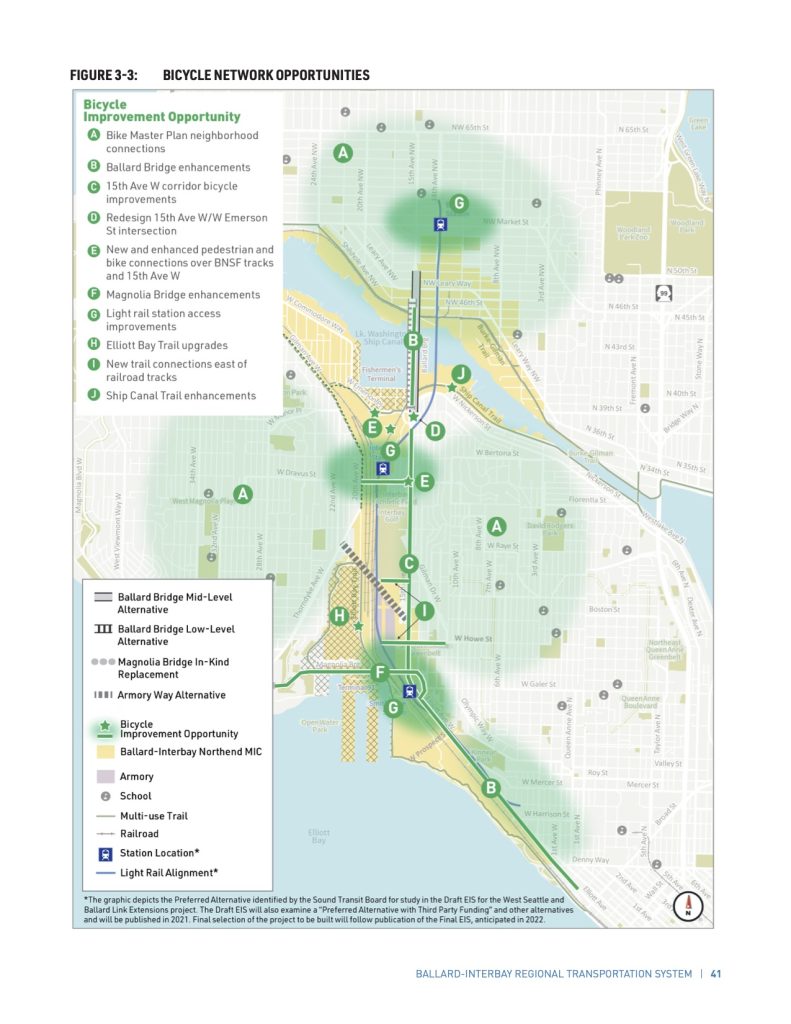

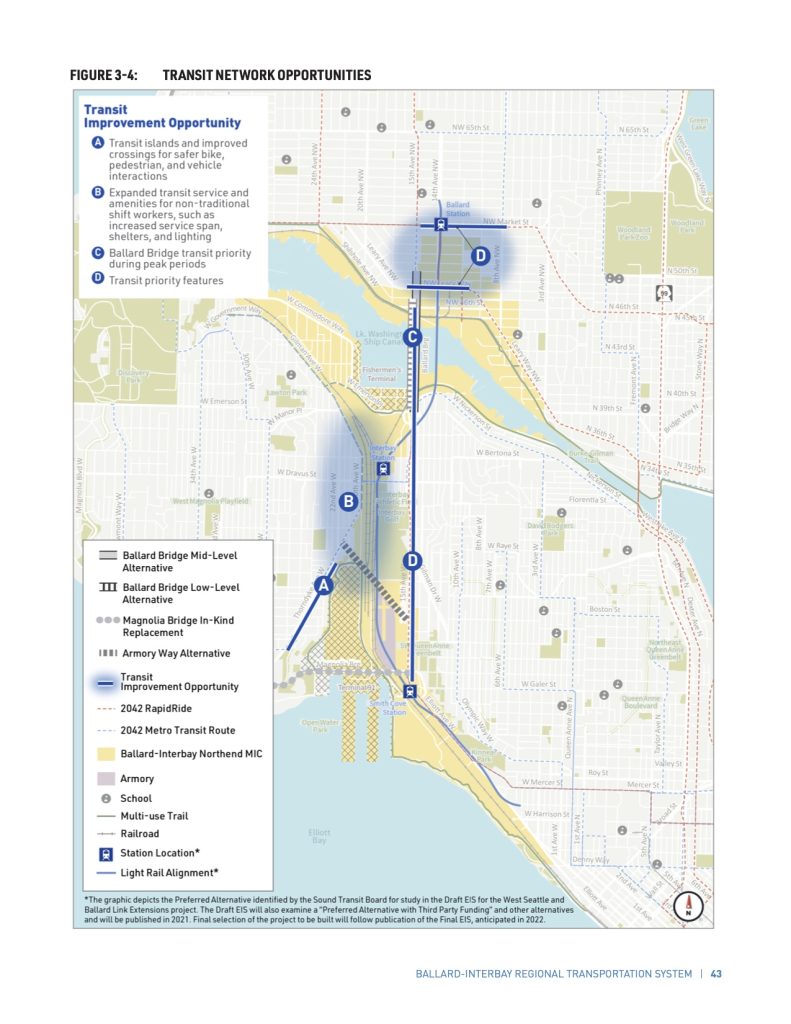

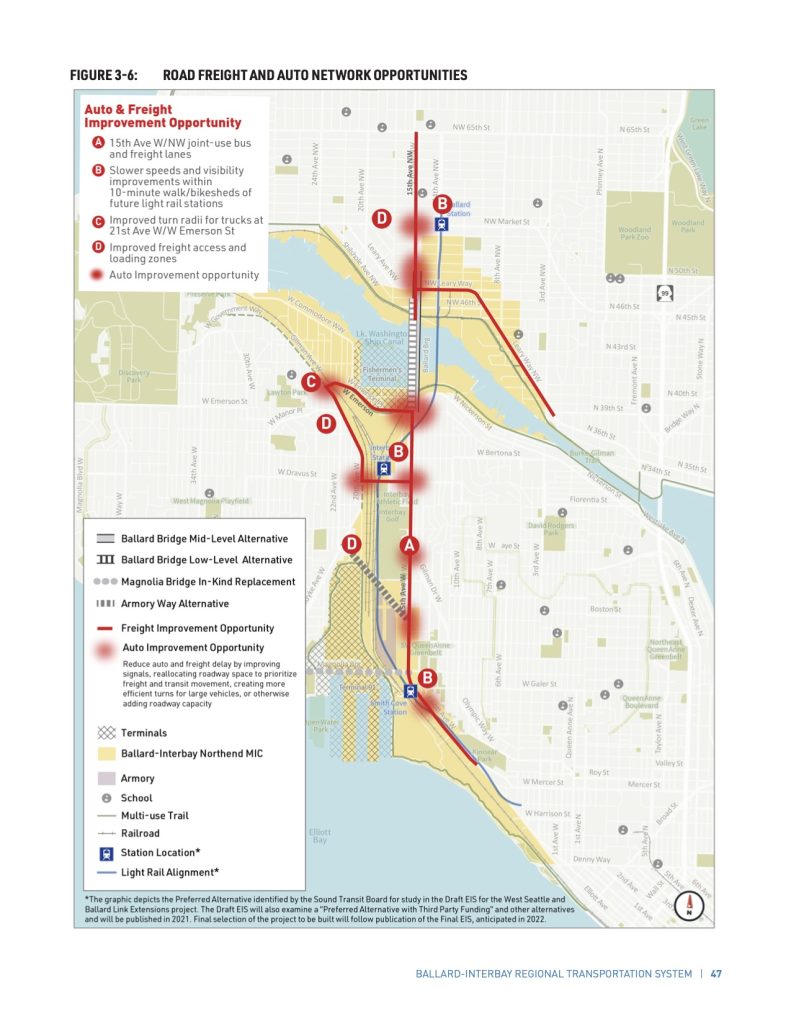

The resulting study is a respectable heft with an extensive series of appendixes. SDOT and their consultants at Nelson Nygaard have culled a list of transportation improvements from two decades of Interbay planning studies. They layered on some scenarios that show most of the alternatives work. The resulting projects are an a-la-carte menu of painted pavement to half-billion dollar bridges. There are some nice maps.

Nowhere does the study put these maps together. There are improvements for walkers, bikers, and cars, but the study falls apart where they mingle. The most extensive consideration of the interaction is at the three brand new light rail stations where the study proposes “slower speeds and visibility improvements within 10-minute walk/bikesheds of future light rail stations.” The study does not consider if there should be freight routes within the light rail walk/bikesheds. The scenarios tested suggest that the only differences in impact between the 1:1 replacement of the Magnolia Bridge and the Armory Way alternative is the cost and impact on driving for a handful of people in south Magnolia. That conveniently ignores induced demand.

This is the core conflict of the BIRT study. It takes too much as given. Without critically analyzing what has actually changed since the earlier reports were developed, the BIRT is just carrying forward all of the omissions and failures of the earlier studies.

Uneasy Handshake

The BIRT and Ballard Bridge studies can be picked apart separately, but we need to take note of the way that the plans cooperate. Working together could be coordination, built from a shared pool of research and findings into something that’s really necessary in this area. Instead, the studies vacuum interlock to create self-referencing justifications for very bad decisions.

The primary example is that south intersection of the Ballard Bridge with Emerson Street and Nickerson Street. A virtually impassible tangle of ramps and stop signs, the current configuration is only slightly better than a field of rusty bear traps.

In all three height variants of the bridge, the study proposes a “Modified Single Point Urban Interchange” allowing free-flow of traffic from 15th on to the bridge with signalized intersections among the flyovers connecting the side roads. The Ballard Bridge study came to this result by deferring on whether this horrible intersection can be moved, noting only the need for merge lanes to Dravus Street further south.

Is it actually necessary to have this intersection at this location? Turning to the broader BIRT study, we find…no answer. In the BIRT study, much of this location and interchange analysis is left to the Ballard Bridge Study. The BIRT Study, as a meta-analysis, doesn’t make these decisions.

The BIRT study leaves it for the Ballard Bridge study to make a thoughtful decision about placement and layout of the Nickerson/Emerson interchange. The Ballard Bridge study leaves it to BIRT to make a thoughtful decision about ramps and merge areas for Dravus St. Neither of those thoughtful decisions were actually made. So the plans then get stuck with one possible design and location for the south ramps of the Ballard Bridge.

This uneasy handshake creates ripple effects. Transit improvements and sidewalks assume this massive interchange. Freight turns are proposed to get trucks navigating through this site. The required size of the replacement Ballard Bridge is estimated based on this huge amount of traffic.

For the higher bridge options, pinning the south side pushes the north end of the bridge deep into Ballard. The middle- and high-bridge options then require insane on- and off-ramps at the north end to compensate. The highest option would put the northern end of the bridge at Market Street. It is impossible to overstate how disastrous it would be to have a massive automobile and truck bridge land in the middle of the vital and busy neighborhood with all the bus lines and the new light rail station.

Two studies, and no one even asks the question of how much of this road actually needs to exist (leaving this work to The Urbanist editorial board.) By carving out space for the other, each study punts on complex questions. We are left with alternatives without true differences.

Unearned deference

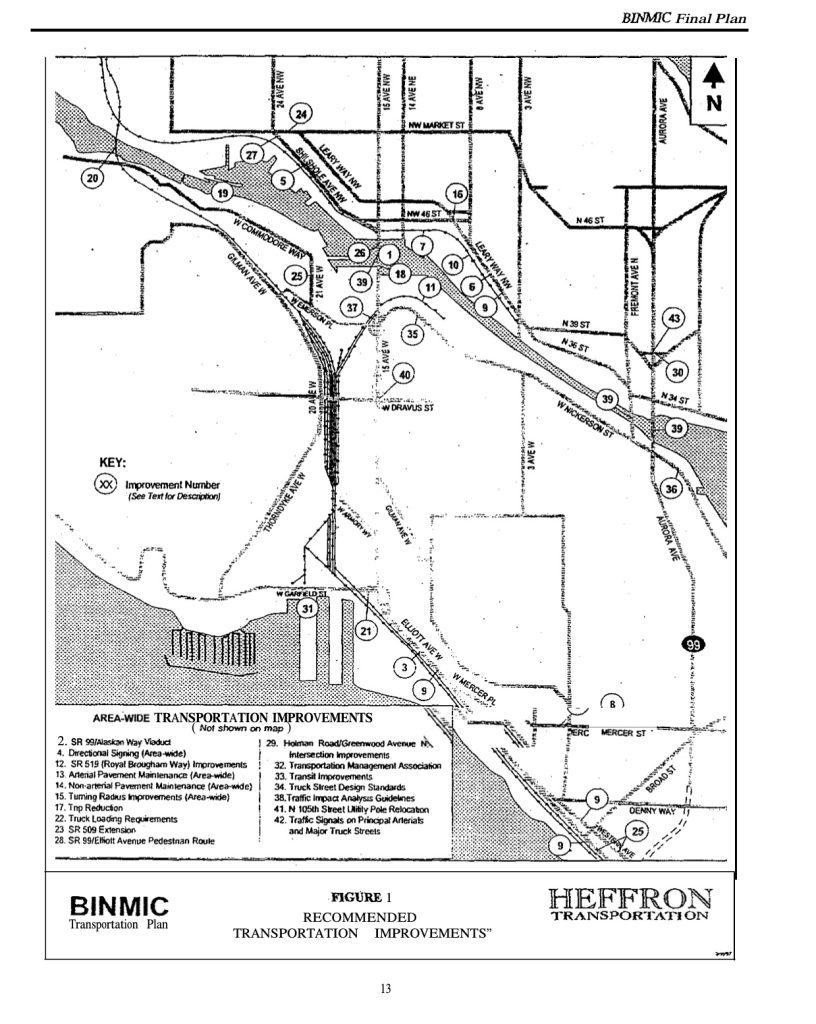

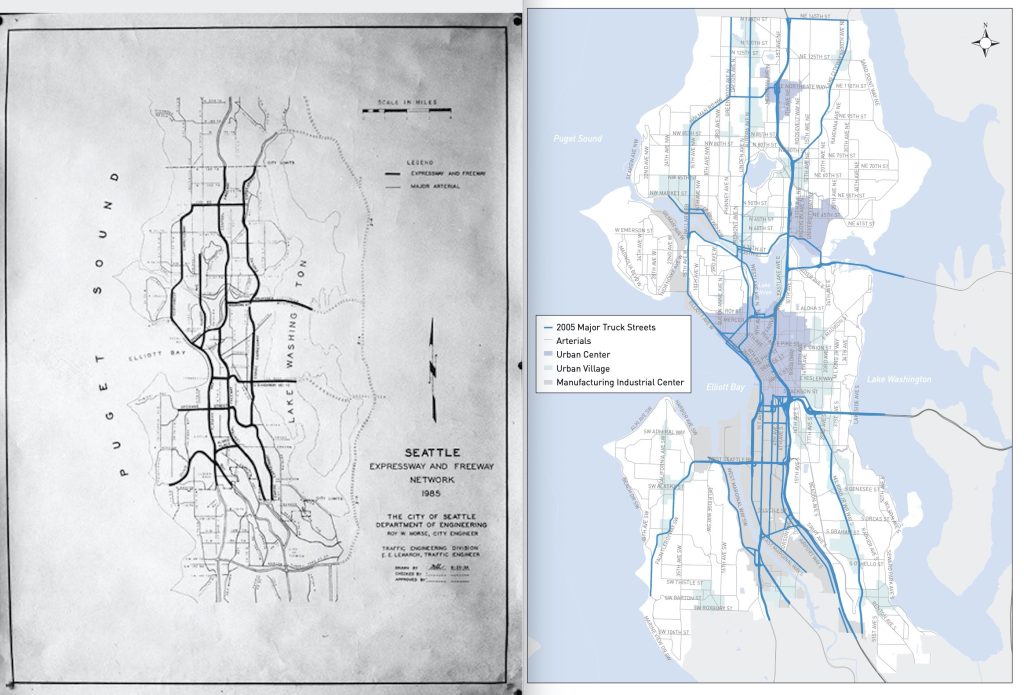

It’s not just the concurrent bridge study where BIRT gives unearned deference. The BIRT is a rehash of earlier plans. But since the BIRT study does not acknowledge any plans from before 2000, it is difficult to see.

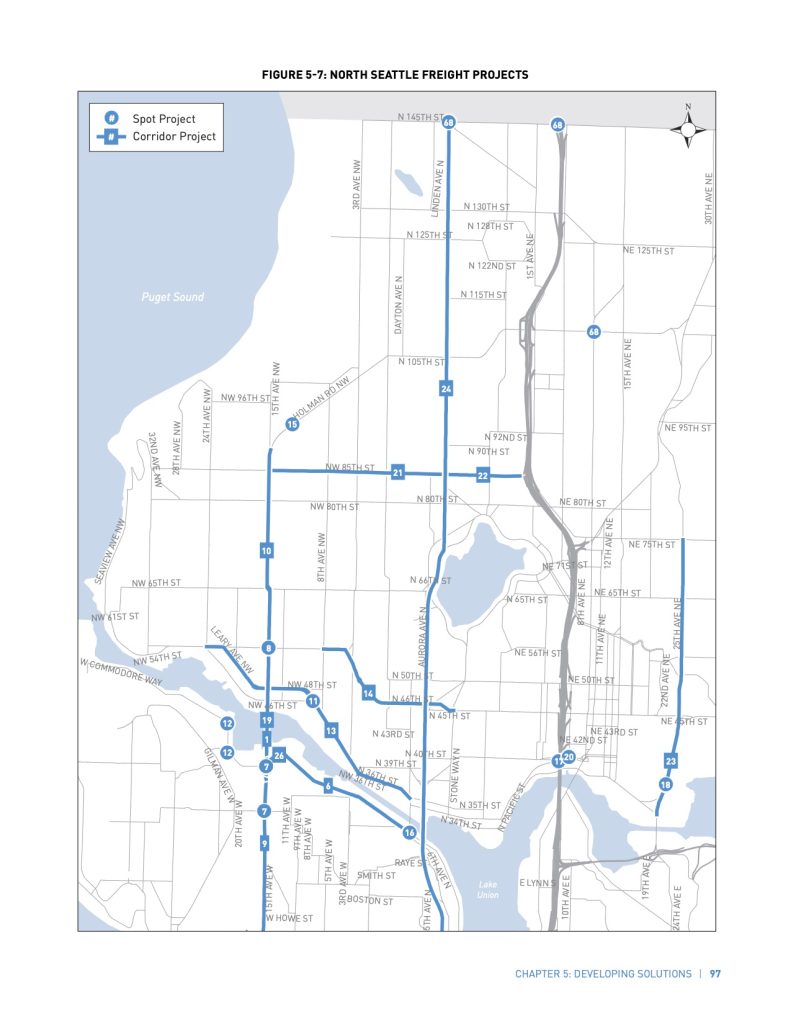

Just tracing one line, the BIRT study includes improvements taken from the 2016 Freight Master Plan. The FMP has 80 some strategies for improving the safety and efficiency of truck freight and concludes with a list of 68 proposed projects throughout the city. Where they focus in Interbay and Ballard, the list includes improvements to 15th Avenue, Leary Avenue, and Market Street,

It is a very familiar list. Most of it is cribbed from the 1998 BINMIC plan. The Ballard Interbay Northend Manufacturing Industrial Center (BINMIC) plan is not mentioned as source material for the BIRT plan. It is too old and outside of their year 2000 cutoff. And, frankly, it should not be part of the BIRT plan because it is a zombie plan that doesn’t address climate change or equity in any fashion.

The BIRT study is an agglomeration of these preceding plans, each of which carried weight of the plans that came before. The BIRT study carries forward the Freight Plan which carried forward the BINMIC. Just like the BIRT study didn’t critically analyze the location of the Emerson/Nickerson interchange, it does not critically analyze any of the other proposed improvements that were carried forward from earlier plans.

Old plans like the BINMIC created the zoning that is allowing industrial land to be taken over by mini-storage and big box stores. Those retail uses are raising the rents on the legacy industrial and manufacturing businesses that the BIRT purports to support. By blindly carrying through the BINMIC proposals, the BIRT cannot get to the root of the issues facing the neighborhood.

Without critical analysis, the BIRT copies and pastes all the baggage of the earlier plans and studies. It is not just an agglomeration of proposed projects. BIRT is an agglomeration of failures.

Premature Plans

The failures of earlier plans in Interbay do not start or end with industrial zoning. None of the earlier documents was created in a vacuum. They carry the prejudices and blindspots of the times they were made. Therefore the BIRT study carries those prejudices and blindspots too.

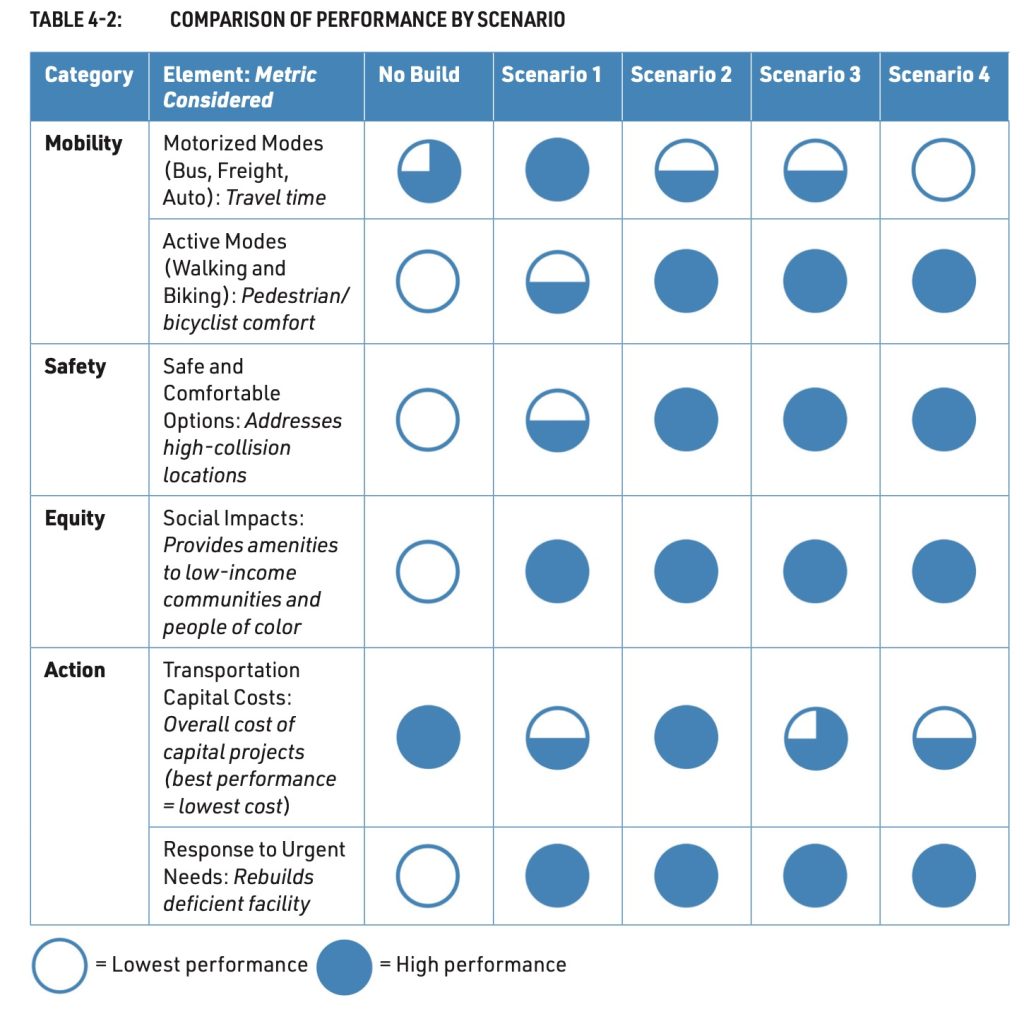

As all plans today, the BIRT study engages a race and equity toolkit to shake out the study’s own prejudices and potential disparate impacts on minority communities. One of the tests for the performance of scenarios is an equity category. The BIRT looks to “Advance projects that meet the needs of communities of color and those of all incomes, abilities, and ages: Build a more racially equitable and socially just transportation system.” All four scenarios are high performing.

Just like the like the Ballard Bridge intersection and projects from old plans, the BIRT study takes equity for granted too. The study’s equity test didn’t find disparate impact in itself, but never scratched the inherent racism of the plans it surveyed. The concentration of industry and highways is systemically racist. We can look at the 1930’s redlining map and see where Covid cases are concentrated. The equity toolkit only looks at whether additional racism is being added. The BIRT study, unsurprisingly, found none and stopped there.

Studies like this never list the baked-in prejudices that come from resuscitating old plans. Plans that never self-examined for equity issues. Plans that never contemplated climate change happening in our lifetimes or even a Cascadia earthquake. Plans that never considered electric cars or high-speed rail or work from home. Each of those earlier plans carry the baggage of the time they were made. By carrying them through, we are stuck with their old socks.

The perspective of a single plan or study is far too narrow to address these larger equity questions. We need something more comprehensive.

Fortunately, that opportunity is right before us. By 2024, cities and counties throughout Washington will make new Comprehensive Plans. Interbay needs to wait. Put the BIRT and Ballard Bridge studies on the shelf. These studies came out too soon, giving an answer before we completed the question. We must get the Comp Plan right before revisiting these issues.

By leapfrogging the new Comprehensive Plan, the Ballard Bridge and BIRT studies may have served a larger purpose. With their failures to address real issues in Interbay, the studies give us a roadmap for the hard Comp Plan work ahead. We cannot simply tinker with the boundaries of urban villages and add charging stations to parking lots. As the Planning Commission stated in their Evolving Seattle’s Growth Strategy white paper, “Seattle’s existing growth strategy needs revision and evolution to firmly establish a racial equity framework that can respond to the limitations we see in its present form.”

The 2024 Comp Plan must be a document founded on anti-racism and fighting climate change. Packaging exclusion in equity koans will not cut it. We must see the status quo for the systemic racism it represents. Every neighborhood must have the capacity to grow and welcome new residents. Antiquated notions of “dirty” industry must face the realities of the green economy. Boundaries–zoning and otherwise–must be completely redrawn so they stop carrying forward generations of segregation.

Looking to 2024 means that we have to wait another three years for real change and vision for Interbay and industrial Ballard. Yes, painful, but it will be more painful to lock in bad decisions. The immense funds for replacement bridges will make their own weather, figuratively by drawing investments in a particular direction, and literally climate arson.

Too often, Interbay is treated as a pass-through, getting none of the amenities but all the traffic and the brunt of the pollution. And way too much junk storage. Rehashing old plans and calling it a study is just another way we drive through and leave trash behind. But not this time.

Interbay is a regional asset, a vital link in our complex city, and a growing neighborhood. It deserves full attention to address a long history of segregation, pollution, and disinvestment. As does the city as a whole.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.