Should Seattle seek inspiration from its northern neighbor’s unconventional transit choice?

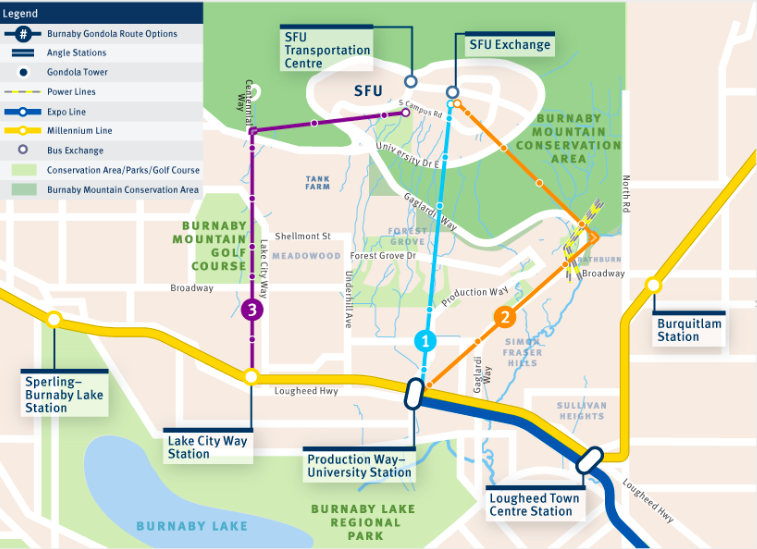

In recent years, Seattle had has its fair share of proposed aerial gondolas, a form of transit that Americans usually best associate with ski slopes. However, urban aerial gondolas having been gaining in popularity worldwide in recent years because of the perks they offer cities in terms of affordability, construction speed, low maintenance costs, and nice views. Gondola transit has been embraced by Translink, Metro Vancouver’s transportation network, as a means to connect the campus of Simon Fraser University on Burnaby Mountain with one of two SkyTrain stations that lay roughly 300 meters beneath. Advocates say its about time that a gondola replace the steep and circuitous bus route that frequently encounters delays and has to pause service entirely in the event of snowfall.

Recently, ten thousand people provided feedback on their preferred route for the Burnaby Mountain Gondola, and Translink anticipates sharing its final project report and route recommendation with local government sometime this winter. Once approved, the gondola project could be constructed in as little as 18 months.

Given the fact Seattle also has challenging topography and a growing need for transit, one might think that gondolas have come under consideration here as well. Yet according to a 2017 Seattle Times article, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has never “looked extensively into an urban gondola as a means of public transportation.” This comes despite the fact that urban gondolas briefly captured Seattleites’ imaginations after Hal Griffin, owner of the Great Wheel at Pier 58, proposed a privately financed gondola to transport passengers between the Downtown Waterfront and Washington State Convention Center. Griffin’s gondola concept made it through a feasibility study, but never advanced further forward for a variety of reasons.

A post by Scott Bonjukian of the Northwest Urbanist captures well the weaknesses of Griffin’s proposal, but during this period more practical ideas for how gondolas improve Seattle’s public transit system were also explored, such as a proposal to connect the Downtown Waterfront, South Lake Union, and Capitol Hill by gondola put forth by Mike Roewe for the Gondola Project. Josh Vredevoogd also created a self-described dreamy map of potential alignments for a Seattle Gondola Network. However, conversations from that period failed to envision where urban gondolas might actually have most the utility in the city: hilly, expansive, and now mostly cut off West Seattle.

Why should SDOT consider gondolas as a transportation solution for West Seattle?

Urban gondolas are not a one-size-fits-all transportation solution, but they could offer some innovative solutions for West Seattle’s current and future challenges.

Shortly before the emergency closure of the West Seattle High Bridge in March, Martin Westerman published an article with The Urbanist about the benefits aerial gondolas could offer West Seattle, entreating local transportation engineers to look for alternatives beyond a bridge or tunnel structure for Sound Transit light rail:

So we look “outside the box” at aerial transit: proven worldwide, grade-separated, enough capacity for West Seattle, and 50% to 80% cheaper than light rail. It is not slope-challenged, and could be delivered to West Seattle sooner–perhaps by 2025 if Sound Transit proceeds decisively.

Now that replacing the vehicle traffic bridge is also on the table, the debate about how to move forward has changed. The recently published Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) seems to have discarded the possibility of a tunnel because of its high cost and environmental impacts, leaving the City with options of repairing the current structure or replacing the bridge.

While The Urbanist has advocated for a bridge replacement option that includes light rail, it does not mean that aerial gondolas, should be taken completely out of the equation. In fact, they were cited as a non-bridge alternative that SDOT was “willing to take a look at” in a June 2020 Seattle Times article, but the transportation mode did not appear in the CBA.

Consider the fact that the Burnaby Mountain Gondola in Metro Vancouver earned one of the highest benefit-cost ratios (BCR) of any proposed transportation project in the region, a whopping 1.8 BCR (a score over 1 indicates benefits exceed costs) which towers over the 1.25 BCR received by the Canada Line, the light rail which connects Vancouver’s Downtown Waterfront with the Vancouver International Airport and the suburb of Richmond.

Why did the Burnaby Mountain Gondola receive such a high score? In addition to the lower construction costs and faster speed of construction, the gondola offers low long-term operating costs. In fact, it is projected to save about $34.5 million in bus replacement costs and reduce operational costs (in comparison with current bus service) by $89.3 million over the next 25 years.

Some strings attached

Of course gondola transit has it weak spots, and one of those is carrying capacity. However, while the gondola’s passenger capacity is less than that of light rail, it is still impressive. The gondola system has been designed to support a capacity of 3,000 passengers per hour per direction. 33-passenger cabins will leave the stations in frequencies of less than a minute and complete the 1.7 mile trip in an estimated six to seven minutes.

SDOT has rightfully cited safety as a major consideration in the question of deciding on infrastructure choices for West Seattle, requiring that any option be able to withstand an earthquake and Elliott Bay tsunami event. Surprisingly, gondolas can be designed to be extremely safe in earthquakes and other natural disasters. The Burnaby Mountain Gondola has been designed to withstand winds of 70 mph. The Portland Aerial Tram, which connects the Oregon Health and Sciences University to the riverfront, boasts that its tram is “exceptionally safe.” It was designed using Swiss guidelines for aerial gondolas that exceed U.S. seismic standards and is equipped with backup power generators to prevent a shut down during power outages. The entire system is also under constant computer monitoring.

In his article, Westerman references two previous gondola studies SDOT undertook in West Seattle, both of which were rejected. However, now that SDOT has been confronted with new challenges–not just the emergency closure of the West Seattle Bridge, but also the City’s budget woes and the need to more urgently address the climate crisis–aerial gondolas deserve further consideration as another transportation option to throw into the mix. Seattle can look not only to Metro Vancouver, but also farther afield to cities like Medellin, La Paz, Hong Kong, and Singapore to explore the many ways urban gondolas can be integrated into public transportation systems.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.