I. Those Left Out: Skyway and Bryn Mawr

It is budget season. Throughout Washington, cities are creating budgets that reflect the dual impacts of pandemic and economic recession. Tax revenue is down. Rainy day funds are depleted. Community groups are applying important pressure to reconsider how we spend our tax dollars, begging it not be used to continue killing Black people.

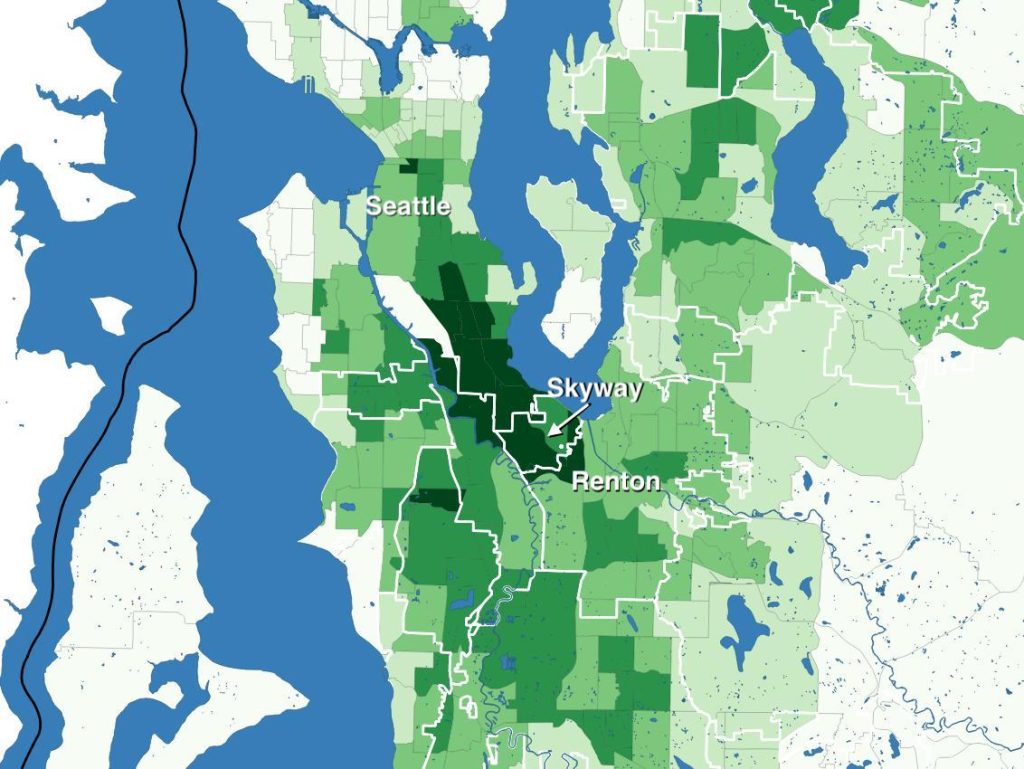

Some communities have been left out of this shuffle. Tucked between Seattle and Renton, just north of Martin Luther King Jr. Way, the communities of Skyway and Bryn Mawr have been allowed to skip budget season for many years. It’s not just left out, but systematically excluded from funding for decades in a misguided attempt to entice one of the neighboring jurisdictions to annex the neighborhood. It didn’t work, and Skyway and Bryn Mawr is still in a netherworld between cities.

So that gives Skyway’s residents a single local elected official. Fortunately that is Girmay Zahilay. It’s hard to believe that County Councilmember Zahilay is technically still in his first year representing the Second District of King County. His unlikely campaign against a political legend and his direct and engaging style make it feel like he’s been around for a while. But this is Zahilay’s first budget season, and he’s making the most of it to put Skyway and the urban unincorporated portions of his district into the conversation.

Neighborhood Attacked

Skyway has been discussed here in The Urbanist a couple of times, but let’s go over some basics. Skyway is a neighborhood of about 16,000 people with no racial majority. The homes are predominately single-family detached and a small commercial corridor runs along Renton Avenue. There’s a Grocery Outlet, a casino, and a couple restaurants.

The neighborhood is bound by Seattle to the north, Tukwila to the west, and Renton to the south. But it is not proper to think of Skyway as the absence of governance. It is more a tidelands, where governance laps in and out with the phases of the moon. In Skyway, services are a matter of convenience for the neighboring jurisdictions and not so much the residents.

Skyway is part of the Renton School District, with three elementaries serving the area. Dimmit Middle School is in Skyway and serves the western portions of Renton down to IKEA. The neighborhood is districted for Renton High School, which is in downtown Renton. Talley High School is an option high school in the Skyway neighborhood.

Policing is performed by the King County Sheriff. The library is a branch of King County. The post office is a Seattle zip code. Bus service–Routes 106 and 107–run through the neighborhood from Renton Transit Center to Georgetown. Routes 101 and 102 go along Martin Luther King Jr. Way S. from Renton to Downtown Seattle via Tukwila. Services in Skyway come from a patchwork of providers.

Zahilay looks at this convergence another way. Without local governance, “Skyway is not shielded from growing Renton and Seattle. It is attacked from north and south economically without structure to protect residents.”

A look at the home prices for Skyway offers a glimpse of what “attacked” means. Though the median income for Skyway is $10,000 less than Renton and $20,000 less than Seattle, average rent is the same in all three jurisdictions. Skyway’s median home value is $514,000, firmly between the neighboring zip codes on either side and increased by 12% over 2019.

But attacked can also mean drained, and that is part of Skyway’s history that Zahilay is trying to correct.

Cities as Agents of Disinvestment

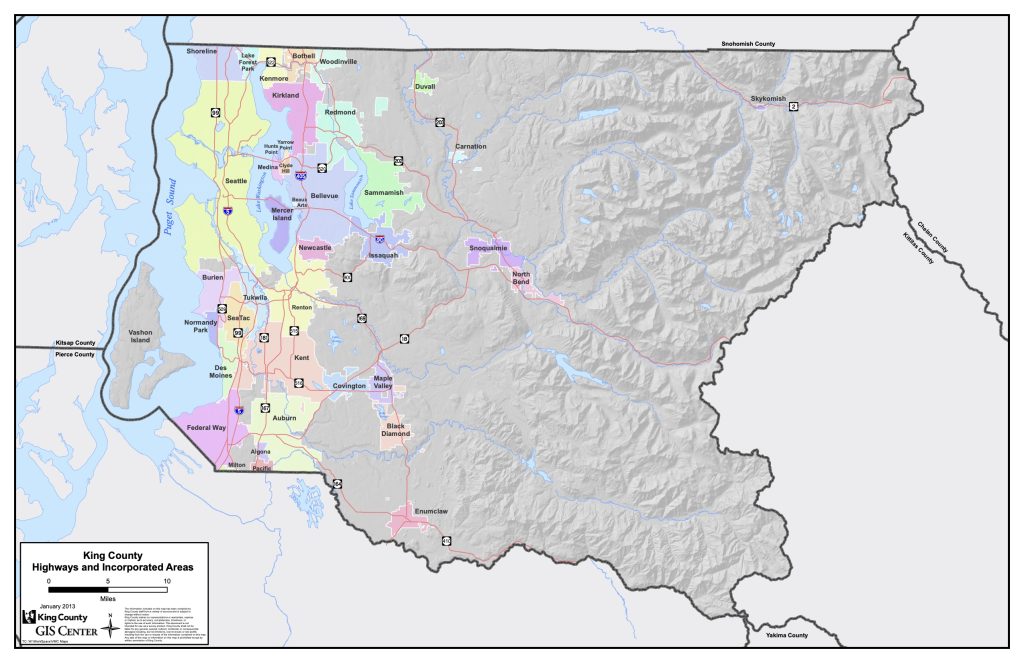

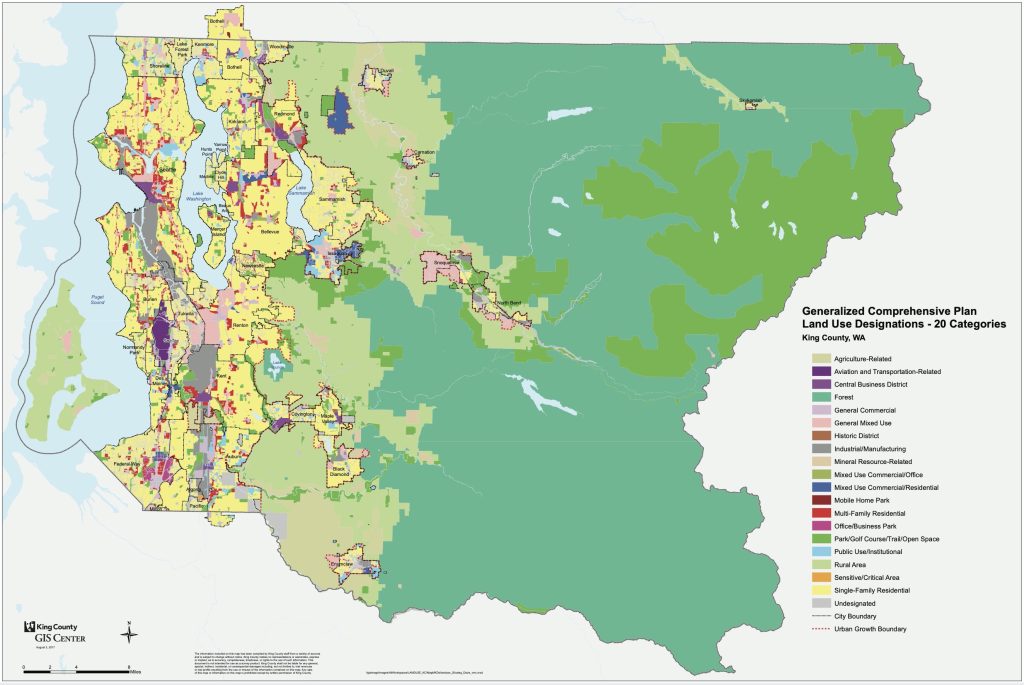

King County has 39 independent cites and towns. Since Seattle’s founding as the county seat in 1869, there have been three waves of incorporations adding cities to this roster. Transportation and industrial hubs like Kent and Renton were established at the turn of the 20th Century. The constellation of east side cities grew up with the automobile in the 1950’s. The 1990’s saw the last wave of new cities, established at the same time as the state’s Growth Management Act (GMA).

Founding a new city is not the only way to get under the jurisdictional umbrella. Absorbing existing neighborhoods in the GMA was promoted by the 2004 King County Resolution 12018, which looked to provide staff and financial resources to aid cities in annexations. Since 2004, half of the potential annexation areas in King County were grafted onto a municipality.

However, along with Skyway, five other neighborhoods inside the GMA are still playing musical chairs. They are mostly developed but the county is their local government. All six have considered annexation to a neighboring municipality within the last 20 years. They were rejected for a host of reasons. East Federal Way has 22,000 people betrothed to Federal Way. Klahanie has 11,000 people in Issaquah’s circle. North Highline/White Center is 32,000 people contested between Seattle, Tukwila, and Burien. East Renton and Fairwood total 32,000 people that would complete Renton’s eastward expansion to the Growth Management Boundary.

In most cases, the host of reasons to reject annexation came down to money. The county resources to assist annexation went to the cities doing the annexation, leaving the unincorporated places without local services like community centers and sidewalks. Since these areas have been underfunded, it would take substantial resources for a city to bring them up to the city’s service level. As Renton Mayor Denis Law put it in 2010: “To provide service to [Skyway] today would require reducing services we now provide to our current residents.” Municipal funding, as always, is a zero-sum game. When that conflict pits folks inside and outside the voting district against one another, it never hurts an incumbent to decide to cut loose the outsiders.

Instead, Skyway is left to pay more money for fewer services and less representation. In 2019, homeowners in Skyway paid $12.14 per $1000 assessed value in property taxes, compared to $10.70 in Renton and $8.28 in Seattle. Everyone pays the same amount in things like the county tax levy, state school levy, and Port levy. But the difference comes in the additional services. Seattle homeowners pay $2.22 to the city with fire, hospital, and library services included in that bill. Renton separates out fire, hospital and library and pays lower rates for each of them than Skyway. Skyway also pays the Renton rate of $3.51 for schools to the Renton school district.

Zahilay is leading a charge to reverse some of the chronic underfunding. The Councilmember’s advocacy has put more than $25 million into the County Executive’s budget proposal directed towards initiatives in Skyway. Correcting a question about successfully getting money “into the budget,” Zahilay points out this is only the very early stage. “The District structure of the County Council makes it that council members understandably serve their own district and battle for funds prioritizing their district.” Skyway faces another uphill battle.

The funds are very early in another process also. Of the proposed funds, $10 million is directed for participatory budgeting in Skyway and White Center. A participatory budgeting process puts more decision making authority into the community, allowing residents to create a list of priority projects to receive the funds rather than having that list made at the council level. The actual process for this decision making is not yet established.

Zahilay sees participatory budgeting as the future. “The most marginalized disenfranchised community members need to be at the table deciding how the budget is being spent. Teaching how the budget is being spent as well as the levers. If you don’t have participatory budgeting, you don’t have any of the levers.”

But the levers of power and decision making have traditionally been denied to communities like Skyway. Through omission, the neighborhood was denied the benefits of belonging to a city. It’s not some passive gradual process of incorporation and annexation that left some neighborhoods unaffiliated. It is active decisions by King County and neighboring communities that denied local governance to neighborhoods like Skyway, disinvesting and exposing it to displacement and exploitation.

Skyway offers a glimpse at something broader. Just because the municipality stops doesn’t mean the city does. Skyway is part of our city, but it is omitted from our jurisdiction. The places we live spill across the inconvenient boundaries we draw. But the boundaries are kept in place nonetheless. Why?

II. The HOA pretending to be a town

The powers of municipalities are defined in state law. The U.S. Constitution has nothing to say about cities, so their governance is left to the states.

Washington law establishes tiers of cities with varying authority. First tier cities, all ten of them with only Seattle in King County, have broad authority to write and pass laws and police their own territory. Second tier cities have more constrained authority, allowed to write laws that are within some general constraints set by the state legislature, but with authority over policing and land use. Towns get the smallest authority, also limited to specific powers listed in state law, and pretty much capped at the size of a single election ward.

One power that is not listed in state law is a power that every city, town, and village exercises every day. From designing police beats to repairing roads, cities make an active map of their territory. They also ferociously define where their authority does not extend. By deciding where their municipal boundaries begin and end, cities have the ultimate power to exclude.

Cities as Formal Entities

King County has 39 independent cities and towns. Since Seattle’s founding in 1869, the county has gone through three major waves of adding to this roster. Around the turn of the 20th Century, the industrial centers and transportation hubs like Renton, Kent, and Kirkland incorporated as independent cities. This wave was brought to an end between the 1910s and 1950’s by war, the Great Depression, and another war.

During the 1950’s a second wave of cities and towns formed on the East side, with Bellevue’s founding and the constellation of Medina, Hunts Point, Clyde Hill. These paralleled the development of roads and bridges, connecting the region through the automobile.

The second wave was brought to a more bureaucratic end. In the 1960’s the State of Washington established county Boundary Review Boards. Finding the metropolitan areas of the state were experiencing “rapid proliferation of municipalities and haphazard extension of and competition to extend municipal boundaries” the Boards’ purpose was to “provide a method of guiding and controlling the creation and growth of municipalities in metropolitan areas.” The law actually includes “preservation of property values” as a driving consideration.

For thirty years, the King County Boundary Review Board tamped down municipal incorporation. That changed by another action by the state, passage of the Growth Management Act in 1990. Creating significant advantages for services and land use planning inside incorporated municipalities, the GMA pushed incorporation. Between 1989 and 2000, ten new cities were founded in King County, which now house a combined 394,000 people.

As we saw with the nibbling around Skyway, founding a new city is not the only way to get under the jurisdictional umbrella. Existing cities can annex adjacent areas. But annexation requires a city or town as the annexing agent. Those jurisdictions get a veto, deciding the extent of their boundaries. Exclusion is a passive but ultimately destructive municipal power when it sets boundaries in stone.

Inelastic Barriers

In his work Cities Without Suburbs, David Rusk observes U.S. cities that experienced the most significant population loss in the second half of the 20th century were hemmed in by incorporated suburbs. Calling this “inelasticity,” he points to cratering populations in east coast and midwest cities like Washington D.C., Baltimore, and Cleveland that were constrained by their surrounding jurisdictions.

Rusk’s central tenet seems to have been lapped in the 21st Century. Many central cities (not so much Baltimore, alas) are doing pretty well, thank you. But Rusk posits a corollary. On a neighborhood by neighborhood basis, inelastic cities show significantly more racial segregation.

King County municipalities are experiencing this racial segregation differently than the “inelastic” cities. Instead of racial minorities being confined to the core city, it appears that the minority population is mobile and pushing southward across municipal lines. However, due to our inelastic jurisdiction boundaries, Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) populations are being divided across separate cities. Six King County jurisdictions have no racial majority. At the moment, King County’s concentration of diverse population has its center in unincorporated Skyway.

If racial populations concentrated into single jurisdictions, King County’s Asian population and Black populations would be the second and third largest cities in the county. The Black population of King County exceeds the population of Bellevue. The county’s Asian population triples that, achieving almost half the population of Seattle.

However, BIPOC populations in King County are mostly locked out of the most densely constructed areas of the county, particularly when it comes to homeowning. Black households make a fraction their White counterparts, and most are unable to afford the increasingly expensive Seattle housing. Statistics suggest that Asian families live in larger, multigenerational households, a house type that is disappearing from the densest areas of the county. By necessity, minority populations are spreading out.

With mobile populations pouring across inflexible boundaries, it is also a question of what is lost. Disconnecting neighborhoods and communities from each other and plugging them into separated tax districts is a type of exclusion. Councilmember Zahilay points out “Seattle is the economic hub of our region. If we want Black people to share in a piece of that pie, all the wealth that’s being generated, we can’t have people being pushed out of city limits and economic opportunities. Especially getting pushed into unincorporated King County.”

The loss is also cultural. As Marcus Anthony Hunter and Sandra F. Robinson point out in Chocolate Cities, The Black Map of American Life, “There is erasure that draws on economic and social boundaries to render places once demographically dominated by Black people to become ‘latte’ and ‘cappuccino’ cities…a complex process of deindustrialization, gentrification, and neighborhood revitalization combine to push older Black residents out even as they sometimes attract younger, but fewer, Black residents.” In Seattle, Black populations are divided from the traditionally Black Central District and Asian-American populations are divided from first-generation homes in the International District by time, wealth, and now political boundaries. All in the shadow of a particular latte company’s headquarters.

HOAs But in Name

The same pattern of migration does not exist on the northern half of Lake Washington. Instead of populations pushing through jurisdictions, traffic just flows by some of the county’s richest neighborhoods, leaving them unaffected. In many ways, these jurisdictions have already pushed many people out to more affordable places. And that’s because the inelastic nature of municipal boundaries has combined with very high rates of home ownership to create a different dynamic: the defacto homeowners association.

Homeowners associations (HOAs) are often bad words, portrayed as fussy, meddling neighbors who can’t stand whimsy or who summon golems to enforce bylaws. In actuality, they are corporations established in state law, just like municipalities. The authority of an HOA is set up in the deed of a house and runs with the sale of the property. A non-profit community corporation oversees the administration of the rules and agreements set in those deeds.

HOAs have one other wrinkle. Elections in cities are based on residency. If you can establish your residency in the city–and there are broad allowances to prove this–you can vote. Contrastingly, HOAs are based those house deeds. Only if you own the house can you vote. No house, no vote.

What happens when you have a city where the only people are homeowners? We know a couple things about home ownership in the United States. Home ownership climbs with age, it climbs with wealth, and it is disproportionately concentrated among White families. Just like expense and unit size are pushing people out of Seattle, a city limited to homeowners would lock out many non-White, non-wealthy voices.

Of King County’s 39 jurisdictions, eleven have over 78% owner occupancy. This is 15% higher than the regional average and in the highest ranges nationally. Sammamish at 86% rates as the fourth highest home ownership jurisdiction in the nation among cities over 20,000 people. It means that there are simply not opportunities to live in these cities without being a landowner.

By default then, these are Homeowners Associations. There is no ability for anyone except homeowners to put a dent in the policies of these municipalities. And that bar has held out as, for years, these communities have kept their municipal tax rates among the lowest in the region. Only facing a catastrophic budget shortfall was one city, Medina, prompted to modestly increase its tax rate–and that only passed by 23 votes.

Such is the power of exclusion. These cities do not have to make any decision that benefits someone outside of their jurisdiction. In the same way that Renton and Seattle do not have to provide more than the most basic neighborly services to Skyway, these municipal HOAs only have to keep their own budgets balanced, not anyone else’s. They also have the full state-granted municipal powers of policing and land use that can keep people outside of their jurisdiction.

While the default HOA cities show the concept of exclusion most plainly, all cities do it regularly. Most recently, eight cities have opted out of the county’s program to house those experiencing homelessness. When it comes to regional solutions, most often for suburban jurisdictions, the power of the purse lies in the ability to say “no.”

Where “social boundaries have been blended by the movement of Blacks,” the immobile nature of jurisdictional boundaries have allowed whites to dilute BIPOC power and reconfigure the regional priorities. Most often this comes from restrictions on the types of housing that support a diverse population, keeping local taxes artificially low, then denying funds to regional initiatives. Where a city like Medina could be collecting tens of millions of dollars from the expensive real estate in the city, they instead claim poverty and non-participation regionally. More importantly, if Medina didn’t exist, Bellevue would be collecting those tens of millions of dollars.That would be the Bellevue with no racial majority and its owner occupancy of 56% standing below the regional average.

Now, there’s one more trick. In some ways, the very wealthy defacto HOA cities are already contributing to revenue for other cities. Through a mechanism called Interlocal Agreements, smaller jurisdictions have outsourced services like education and policing to other places. This is the case for most services among cities like Yarrow Point, Hunt’s Point, Medina, and Clyde Hill.

It’s very similar to the a la carte way unincorporated Skyway pays for services. Except Skyway pays vastly more money for less services because they do not have consolidated representation to negotiate on their behalf.

Worse, the web of interlocal agreements that’s developed between municipalities creates a secondary network of agencies and authorities that divide and exclude like municipalities, while reinforcing the inelastic barriers to change.

III. Overlaps

The Seattle Times would like you to vote against an appointed Sheriff.

On this year’s ballot is King County Charter Amendment Number 5, which would replace the elected King County Sheriff with a person appointed by the County Council. The Times doesn’t like that idea. (The Urbanist has much better endorsements.)

The Editorial Board’s rationale for this is three-fold. First, in 1996 the voters made the Sheriff an elected position by 57% of the vote. Second, the Seattle City Council’s work to defund and reform SPD “show the danger of micromanaging law enforcement.” And third, cities from Woodinville to SeaTac pay the sheriff’s office to act as their local police and may reconsider their contracts with an appointed head of the department. Dave Reichert, former 8th District Representative, submits an additional argument that only an elected Sheriff caught the Green River Killer. Because, you know, only elected officials really care about gruesome serial killings.

We can understand the shape of our cities by looking at neighborhoods like Skyway that have been left out of city boundaries. We also begin to understand how these holes were created by the waves of incorporation and annexations that laid down inflexible jurisdiction boundaries.

There’s a third pole holding up this tent. The sheriff’s office and a number of cross-jurisdiction agencies give us another way to understand the powers and dangers of the patchwork municipal governance.

Cities as Contractors

You’re getting to know this part. King County has 39 towns and cities. They range from 205 people in Skykomish to 747,000 people in Seattle. Homes in Algona average $250,000, while in Hunts Point they average $4 million a pop. Seven jurisdictions have no racial majority.

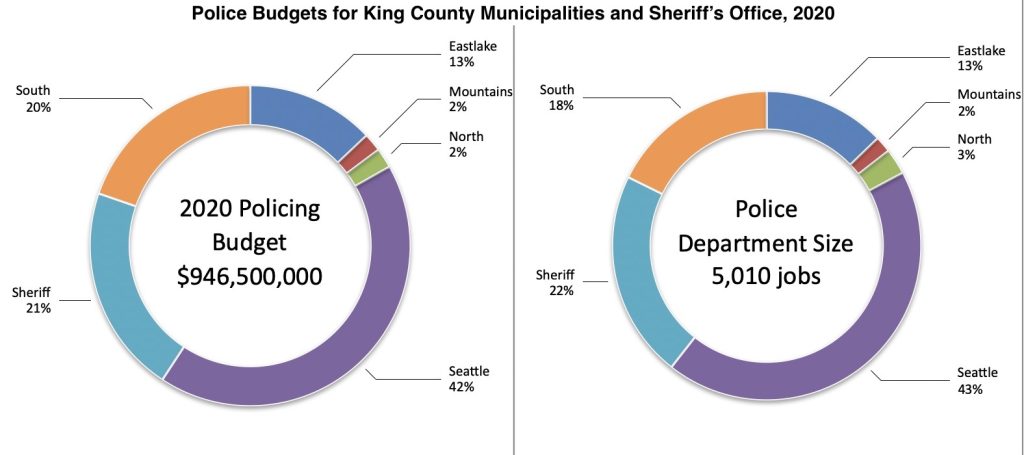

These cities sort into other groups. The county has 20 school districts and 26 police departments. Among these police departments, there are 5,000 employees and almost one billion dollars in funding. Twenty-eight cities contract to send arrestees to a jail facility that is owned by six of the jurisdictions.

There are 20 school districts in the county. Mercer Island is the only one bound within its city limits. Every other school district includes parts of several jurisdictions.

Currently, Sound Transit light rail only connects three jurisdictions–Seattle, Tukwila, and SeaTac. Stops open over the next few years in Mercer Island, Bellevue, and Redmond. Construction continues towards Shoreline. The other 32 King County jurisdictions continue to pay for Sound Transit with little prospect of light rail connection, explaining the disparity in votes cast for and against I-976.

But some of these breakdowns paper over the ways that King County’s cities and towns rely on one another.

Interlocal Agreements

During our discussion of towns acting like HOAs, we put a pin on the idea of Interlocal Agreements. These are the formal agreements sanctioned in state law that permit jurisdictions and public entities to enter into contracts with one another. Let’s return to that discussion.

There is no master list of interlocal agreements between King County’s jurisdictions. King County has a partial list of their own agreements about trails and road service and stuff like that. Larger municipalities are pretty good about keeping interlocal agreements publicly accessible. For example, Tukwila and Bellevue have theirs online with links to the actual resolutions. You can pull up the contract allowing Tukwila to get hearing examiner services from Seattle or Bellevue to provide services to Mercer Island residents with disabilities.

The smaller jurisdictions do not provide continuous records in such an accessible way. Some interlocal agreements are included as documents on individual meeting agendas. But for most of the small towns, you have to backfeed from the records of a larger jurisdiction.

The only system that’s worse is, of course, the largest municipality. Seattle does not have a method to search interlocal agreements. There is a location in the Purchasing Department’s website that will give you a PDF of the cities Seattle can buy stuff from, but not the other ties between municipalities. Even the Seattle School District has a better and more searchable interlocal agreement page than the City. Seattle is a first-class city with a third-class website.

But the useful, searchable databases give an idea of the extent of interlocal agreements. Bellevue lists 1,112 individual agreements since the earliest records in 1999. Tukwila breaks it up a little differently, with about 200 interlocal agreements over the last decade (but their superb system goes back to 1978.)

Even without a comprehensive way to chart all of the interlocal agreements, one begins to appreciate the shape of the formalized arrangements between the county’s many jurisdictions. Some are for the big stuff, like Bellevue’s contracts to provide fire and EMS to its neighboring jurisdictions. Others are for more modest services, like North Bend’s agreement with the Regional Animal Services of King County to receive animal control services.

The interlocal agreements also highlight how power and authority is distributed around governments, not just among the towns and cities, but also among shared entities and public districts. For example, there is the interlocal agreement between Seattle and the Seattle Parks District (not found in the city’s interlocal agreement page). The Parks District was formed by the city in 2014 as a mechanism for stable tax revenue. But in forming the entity as its own municipal organization, the City and District had to formally agree upon shared and exclusive powers.

And interlocal agreements go up and down in scale. Jurisdictions’ participation in the Puget Sound Regional Council are based on an interlocal agreement that establishes PSRC “shall ensure implementation in the region of the provisions of state and federal law which pertain to regional transportation planning and regional growth management.” It is also the document that lays out the system of voting powers based on population.

It is not improper for cities and towns to enter contracts with private entities or each other. When a town spends a lot of money on a great park, open it up for programs to the region. What comes in to question is when do these contracts reach a critical mass that demands the need for something else. What’s the tipping point? When they become untraceably complex? When they divest core municipal authorities? How about when they prevent necessary change.

Public Safety

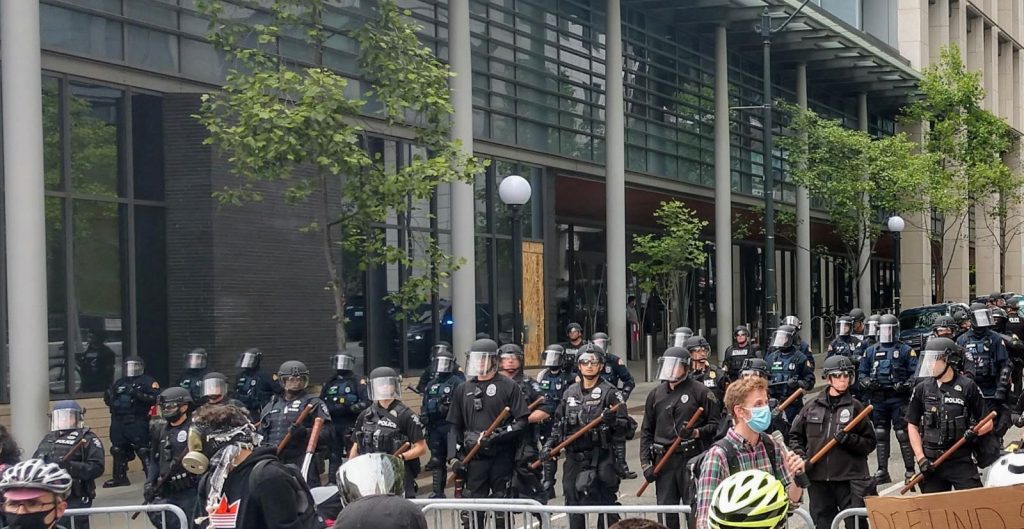

The recent headlines about public safety, both locally and nationally, have been the movement to defund the Seattle Police Department. With a $400 million budget that has grown in recent years even as public sentiment considered the department increasingly ineffective if not downright dangerous, the movement to cut SPD’s budget by 50% has received a lot of attention.

What’s often overlooked is that Seattle police are only a portion of a larger network of policing throughout King County. Of the county’s 39 jurisdictions, 24 have police departments. On average, municipalities spend 26% of their budget on policing and no town spends less than $250 per citizen on policing each year. There are 4,000 employees of King County municipal police departments.

Twelve cities forgo their own police departments and contract with the King County Sheriff’s Department. (The other three towns–Hunts Point, North Bend, and Yarrow Point–contract with a neighboring city.) While many rural sheriffs had policing duties, sheriff departments in urbanized areas with city police departments are more judicial, charged with overseeing court orders and evictions. These contracts with municipalities allow the King County Sheriff to continue its judicial work as the county sheriff while providing local policing to the contract cities and unincorporated areas.

Kathy Lambert, Councilmember for King County District 3, sees the collaboration as beneficial. “We do a dang good job of being a contract sheriff department. In the contract cities, they’re happy. If they weren’t, they wouldn’t contract with us. And they’re all very happy with their services. Sammamish made a concerted decision to contract, that’s their way of keeping overhead down.”

That’s why Councilmember Lambert echoes the sentiments of the Seattle Times Editorial Board in opposing the King County charter amendments to make the Sheriff an appointed rather than elected position. She points out that many of the contract cities have passed resolutions calling for rejection of the proposed amendments. Lambert sees the current system working and responsive. “Of course it works. The [municipalities] get to ask for hours and specialists and sheriff hands over a bill. If there’s a problem, the mayor calls me or the sheriff and it gets handled in 10 minutes.” An appointed Sheriff, she warns, would risk these contracts.

Broader than local policing, other segments of public safety are also provided as services by jurisdictions to one another. Police dispatch services in the King County suburbs divide between the Valley Communications Center in the south and Norcom in the north and east. The two systems are governed by a series of interlocal agreements between various cities, regional fire authorities, and other entities like the Port of Seattle.

Most jailing services for county municipalities are contracted to the South Correctional Entity (SCORE), which is a jail in Des Moines constructed by seven south King County cities under a Public Development Authority. Costing $54 million in 2011, the facility holds 803 inmates. There are six “owner” members remaining as Federal Way left the consortium due to rising cost of housing prisoners. Thirty three other jurisdictions and agencies contract with the PDA to use the facility. It is unclear what the current population of SCORE is after Governor Inslee’s reductions imprisonment due to Covid restrictions.

Now, this is just three aspects of public safety in King County. However, there are thousands more agreements covering parks, animal control, fire districts, school districts, and a host of other ways cities cooperate. In just these limited public safety issues of jail, communications, and sheriff’s policing, there are 56 separate but coordinated interlocal agreements (five communications, 38 SCORE, two SCORE ownership, 13 sheriff, three town). Each of the jurisdictions involved has a vested interest in continuing the operations of the contract, facility, or authority that they’ve signed onto.

None of them include the City of Seattle.

The Invisible Buttresses

Taken together, policing is a billion dollar business in King County. When Seattle discusses defunding its $400 million police department by 50%, that still leaves $800 million of policing in the county.

Besides money, there are layers of cooperation between jurisdictions working against broader reforms. At the top level is the contracted cooperation between cities. More than just the array of interlocal agreements, all jurisdictions coordinate to respond to large emergencies. Some of these relationships are so convoluted, they are not immediately evident. When Seattle’s police were called in to support the Port of Seattle police and Immigration and Customs Enforcement through a mutual assistance agreement, even the Seattle City Council was caught off guard.

There is also a more subtle cooperation between employees of police departments, sometime against the cities they work for. The police play their respective city halls off one another for preferred benefits and salaries. The proximity and easy movement between departments are also used to oppose police reform. For example, the “blistering” commentary on the way out in police exit interviews was used to tamp down reform in Seattle in 2019. The exact same trope is being used again right now.

Councilmember Zahilay recognizes the issue as a vote-counting challenge against the proposed charter amendments. Speaking of reform in the county versus Seattle proper, “It’s a lot harder,” the Councilmember observes. “With Seattle you have one mayor and council in charge. It’s still hard and contested. If we’re talking King County, if we’re trying to make structural changes, we have unincorporated places and contract cities with their own full time advocates. They’re doing what their constitutions ask them for. There are way more structural obstacles. One more thing we have to work through.”

Unfortunately, with the knot of interlocal agreements, one more thing brings in ten of its friends. Interlocal agreements are a method that cities collaborate, but it is a very selective collaboration. The effect of interlocal agreements is to collude to reinforce hard, exclusionary barriers within the broader city.

IV. Those who want to escape

On Thursday, October 29, Town Hall is hosting a discussion called “Is Seattle Becoming Ungovernable?” with Joni Balter from Civic Cocktail, Dr. Larry Hubbell from Seattle U, Councilmember Debora Juarez, and former KC Executive Ron Sims, the discussion looks to unravel six months of protest, unrest, and “consider a way forward” for this “anarchist jurisdiction.”

The ungovernable-ness of cities comes up at times of turmoil and stress. Even at their most proper and presentable, cities are messy and unruly places. Besides the noise and crush and issues there’s always the sheer numbers of people and buildings and all the stuff that makes cities awesome. When that crush turns to protest and those noises turn angry if not violent, all bets are off. Except for one, that someone will try to make a comparison to Detroit.

But ungovernable? There were demonstrations against police brutality in every corner of King County and the region. No one has asked if Bellevue is ungovernable, or Olympia, or the State of Washington. This is a label, like “anarchist jurisdiction” that gets selectively saddled on core cities.

And really, asking if a place is ungovernable depends what you expect governing to do. If you expect governing to keep the city proper and presentable through some rationale division, well you got another thing coming. From Skyway to HOAs to interlocal agreements, we are seeing that we try to set up smaller localities to make governing easier and more local, and they mess up a lot of stuff too. Those clean lines between all those municipalities are actually part of the problem. They divide up groups of humans, exclude many, and get into their own special brand of confusing interactions.

So maybe it’s time to try something else than cities.

Cities as Regional Entities

One last time. King County has 39 towns and cities. Together they make up 90% of the county’s 2.1 million person population. They are just less than half of the 82 towns and cities in the Puget Sound region. With Kitsap, Pierce, and Snohomish counties, the region is 4.2 million people.

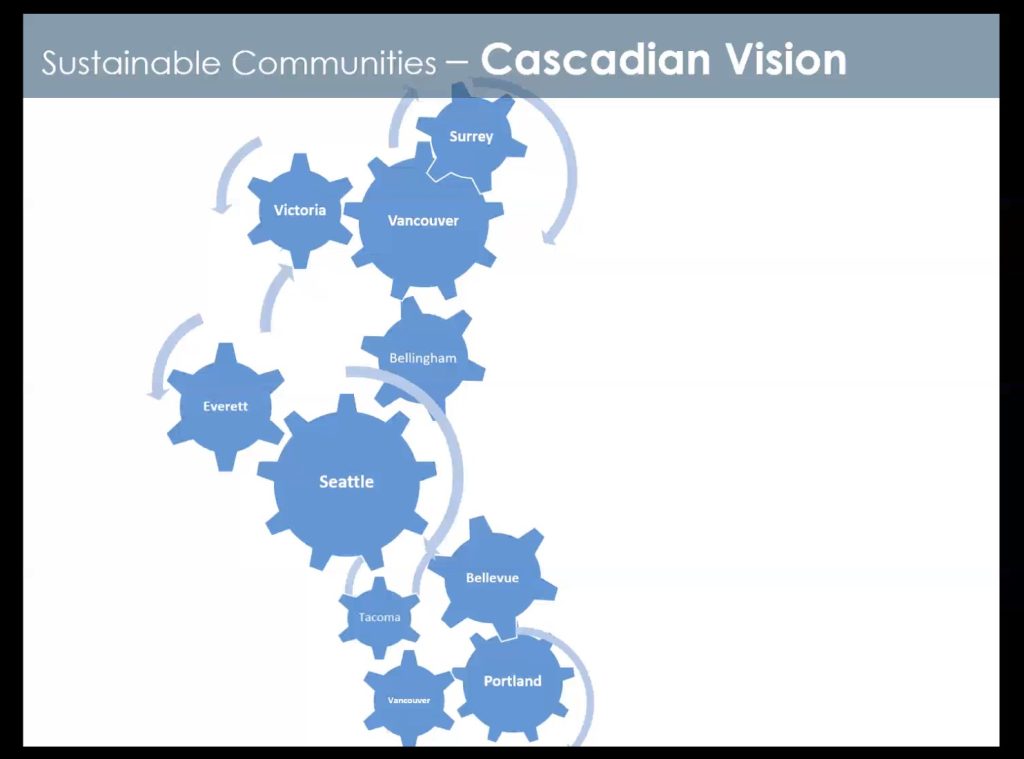

The Puget Sound region is itself a part of the Cascadia Corridor. Seattle’s position is smack in the middle of the 16 million person region, equal distance from Portland and Vancouver, both housing 2.4 million people in their metro areas.

Most of our discussions of regionalism and megalopolis start with these building blocks. Core cities, orbited by dense clusters, surrounded by cohesive network of highways and bedroom communities. But what we have seen is that the uneven governance surrounding Seattle does as much to define the city and the region as any slow drone video orbiting the Space Needle.

It’s this uneven governance that drives some advocates to visionary visions that envision a Different Way (that happens to be somewhere else).

Rural Enterprise Zones

To hear Councilmember Kathy Lambert discuss issues facing the county is to get a lesson in balance. We need to balance dense development with the impending limits of our sewage treatment facilities. Covid will prompt a rebalancing of high and low buildings as people avoid shared hallways and air systems. The pandemic will rebalance the transportation system away from transit and back towards cars.

Councilmember Lambert saves her most critical discussion of balance for the region under the Growth Management Act. “There are the 14 GMA requirements. They are very specific about saying none is more important than the other… Looking for balance is not happening. All the sustainability is not happening.”

She points to the separation of rural residences from revenue creating commercial areas. The GMA was drawn around most commercial areas, with jurisdictions annexing to the boundary. This has left rural areas outside of both cities and the growth management area with stark tax consequences. “The GMA said that the unincorporated area has to be sustainable. They have tried three times to [revise] the GMA said and haven’t been successful. That means we don’t have the services that others in the county have.” Saddling the unincorporated areas with keeping broader infrastructure in place is not balanced. “We are $400 million behind in roads. We have a $40 billion asset and no money to take care of it. We will have 35 bridges and miles of roads and we don’t have the money to take care of them.”

This results in one conclusion for Councilmember Lambert. The GMA is another indelible line dividing King County residents from community resources. “If they are not in balance, we have to move the Growth Boundary.”

As unincorporated jurisdictions within the GMA are annexed, the amount they contribute directly to the county for roads and services will be redirected to a municipality. This will result in a decreasing amount of revenue supporting the broader unincorporated parts of the county.

So the Councilmember is advocating a concept of Rural Enterprise Zones, establishing locations for clean industrial and commercial development at highway intersections in rural King County. “Enterprise zones two to three places in the county that can generate $400 million with good and clean businesses that can be sustainable as a community.” She sees this as a tax base for the 6% of the King County population that projected to be outside of the GMA and municipalities.

The first location is obvious. “Put it at the intersection of SR-18 and I-90. Two highways people would stop. Groceries and cleaning where there’s no way off I-90 and SR-18 backs up.” She looks at the new Aroma Coffee Company in unincorporated Falls City. “That is acting as a community center. There are cars lined up outside. They had to go back and find the original knives for restoring the wood trim.”

Really, a new cluster outside the growth boundary is the only alternative for Councilmember Lambert because working within the bounds and regulations of the GMA, “has not given me any way to make my unincorporated areas sustainable. Unincorporated areas are unsustainable, no one has come to meet those problems.”

Hub Cities

At the same time Councilmember Lambert is discussing rural enterprise zones, other groups are arriving at the same conclusion, just in a north-south alignment.

The Cascadia Innovation Corridor is an initiative crossing both state and international borders to connect Vancouver, BC, Seattle, and Portland. The groups goals in easy transportation and talent building through education look to boost the life sciences, tech, and sustainable agriculture throughout the Pacific Northwest. The steering committee is headed by former Governor Christine Gregoire and the group is supported by chambers of commerce in all three regions, various technology associations, and Microsoft.

Stealing the name of PSRC’s Vision 2050 blueprint for growth, the group developed a plan called Cascadia Vision 2050. As pointed out by Natalie Bicknell, the concept fights sprawl and increasing commute times by refocusing growth along a spine of high speed transit. The location of the most growth, proposed by the group, is within “Hub Cities”. These would be new developments in the corridor, spaced 40 to 50 miles outside of existing cities, and concentrated along stops on the high-speed transportation network.

For those playing at home, the Cascadia Innovation Corridor reinvented Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of To-morrow. Howard, of course, conceived a development scheme to relieve the congestion and pollution of turn-of-the 20th Century London, Garden. It’s a ringed plan, that’s so steeped in Victorian steampunk it should have a leather coat and goggles. A mainline railway loops concentric rings of houses and gardens. The rings step up in density towards commercial spaces in a Crystal Palace that itself surrounds a Central Park. Areas outside the loop railroad

Jane Jacobs said Ebenezer Howard “looked at the living conditions of the poor in late-nineteenth-century London, and justifiably did not like what he smelled or saw or heard. He not only hated the wrongs and mistakes of the city, he hated the city and thought it an outright evil and an affront to nature that so many people should get themselves into an agglomeration. His prescription for saving the people was to do the city in.”

One of Howard’s most famous illustrations shows Jacobs point. Titled The Three Magnets, Howard tries to illustrate the characteristics that push and pull towards the “Town” and the “Country.” Contrasting development and pollution, and opportunity and peacefulness, the two initial alternatives beg for a third, which Howard calls the “Town-Country.” Here he took all the benefits of the other two with few of the downsides. In the Town-Country, the Town’s Army of Unemployed and Foul Air and Murky Sky are replaced with the Country’s Field for Enterprise and Parks of Easy Access. The Country’s Lack of Amusement and Low Wages are replaced with the Town’s Flow of Capital and Social Opportunity. Hub Cities simply updates this chart with commuting times and green house gases.

Microsoft of all groups should really know better. Forty years ago, they staked their flag in sleepy Redmond, an exurb business park. For that effort, they got impenetrable traffic and their lunch eaten by upstarts who decided to locate downtown and not be cloistered into ideas like Bing and Zune. The last fifteen years has seen Microsoft plant towers in Bellevue, cajole light rail out SR 520, and develop a plan to turn its once pristine office park into an almost walkable village.

But the proposal gives us an interesting lesson on inadvertent visual allegory. Presenting the Cascadia Vision 2050 to a Zoom meeting on October 9th, representatives of the Innovation Corridor put up an image of the cities in the metroplex working together. Between Surrey and Portland, they identified ten gears.

Which, of course, leaves out the hundreds of cities, towns, and unincorporated neighborhoods. As well as the county governments. And the cross jurisdictional agencies and authorities. In an image of giant gears, all those extra players are just sand. It is yet another level of exclusion and omission, this time under the guise of being visionary.

A macro vision that conveniently papers over the small grit is also giving a perhaps unintentional, but absolutely clear answer to “is Seattle ungovernable?” Plans like Hub Cities and Rural Enterprise Zones say that the existing confines of municipalities and jurisdictions is simply too confining. For Councilmember Lambert, the answer is to head to the mountains. For the Innovation Corridor, the answer is to add another gear.

These proposals suggest a need to escape to a better place. It is actually a reluctance to engage in the world that is. Hub Cities and Rural Enterprise Zones are just another way of saying “it’s too hard, I’m taking my ball and playing by myself.”

The City of Skyway

Powerful forces of omission, exclusion, and collusion shape our city through the ways it is governed and ungoverned. Calling the city ungovernable and trying to leave it all behind is just the same routine in another form. It sets up another inelastic barrier, puts people and resources beyond it, then prepares to complain about how ungovernable the new interactions will be. Over the last 100 years, we have tried the Enterprise Zone and Hub City ideas. We just called them Redmond and Kent. In an earlier generation, we called them Georgetown and Ballard.

Realigning municipal boundaries and expectations does not come without a cost. In his book railing against a single-city metroplex, Knute Burger starts “I’m not sure when I stopped living in Seattle and became a resident of Pugetopolis. It could have been years ago. It could have been at birth. Seattle might always have been a myth.”

Berger goes on to observe the impacts of “competition for affection and approval of the robber barons” that drove establishment of the busy ports around Puget Sound, the transportation hubs on Lake Washington, and the speculative communities that sputtered and died throughout the region. “The legacy of greed set up a dynamic we have to this day, a competitive balkanization. The cities, counties, towns, and suburbs of puget Sound still compete, still view their futures through the eyes of self-interest and suspicion.”

There are other legacies wrapped up in the region’s balkanization. “We can talk lines and resource allocation,” Councilmember Zahilay. “Just the fact that some races and demographics work in low wage jobs that keep them busy all the time is a structural barrier. Redlining left some races unhealthy is a structural barrier. The way our education is funded through property taxes leaves some unprepared to advocate for themselves. We can go down the line from education health, criminal justice, leaving people unenfranchised permeates every aspect of life. I think people don’t see how systemic racism and generations of unjust policies permeate every part of daily life.”

Human beings drew those lines and built those legacies. We see it over and over again with borders throughout King County. Jurisdictions acting in their own best interests set boundaries that work great for their own municipalities, but work to omit and exclude in ways that damage BIPOC communities and the city as a whole. It is disparate impacts cooked into everyday activities.

As Councilmember Zahilay points out “systemic racism doesn’t need intent to harm. The intent is irrelevant if the outcome is harm to Black communities and communities of color. That’s what’s happening in Skyway. A community with 70% minority population is disinvested with the hopes it will be annexed.” It doesn’t require people to input additional racism or conspire to carry out a plot against Blacks. Our predecessors have set up a system where “it’s people advocating for their communities that leads to harm for Black people. That’s the definition of systemic racism, it doesn’t require intent.”

We’re moving to a point where it takes intent to continue. Beyond just understanding why these municipal lines exist, we’re being asked to sustain the indefensible. Our municipal boundaries have gone beyond simple lines between towns and tax districts as they become barriers of omission and exclusion. Worse, the organizations within the lines network together to reinforce this exclusion and resist necessary reform. This is the Patchwork City.

For a long time, it was very easy to pretend that there was no problem with the way King County and the greater region divided and oppressed and assaulted communities of color. Again, no inputs is how systemic racism works best. But tireless work by advocates like Councilmember Zahilay and groups like King County Equity Now and the Seattle City Council and thousands of activists that spent the entire pandemic summer and fall protesting, the impacts of systemic racism are repeatedly thrust into the news. It is taking more energy to ignore the problem than it is to recognize it exists.

But conceding change is necessary is still an infinitesimal amount of energy compared with what it would take to break down jurisdictional barriers. It is easier to throw on another patch. The ranks of cities, county agencies, public authorities, and interlocal networks that line up to hold these barricades seem insurmountable. These are independent agents working in their own self interest, resisting needed change and preventing an equitable city. Again, structural racism at work and we’re too busy to change it.

That is why Skyway speaks volumes about how we define ourselves as a city. Not the jurisdiction of Seattle, but the living, breathing metropolis of Seattle and Bellevue and Renton and Martin Luther King Jr. County and Pugetopolis and Cascadia. Whatever name we pick for this metroplex, whatever iconic landmark we put on a sports jersey, whatever chamber of commerce presentation about regionalism, nothing can characterize our home more than the line that segregates Skyway from the rest of the city.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.