Bellevue, Renton, Issaquah, Maple Valley, North Bend, Covington, Snoqualmie, and Kent voted to opt out of King County’s homelessness measure by proposing their own city-based packages focused on higher income housing.

Last month King County Executive Dow Constantine unveiled a plan to raise $400 million to create 2,000 homes for people experiencing homelessness. The permanent supportive housing plan rests upon bonding off a countywide 0.1% sales tax increase the King County Council approved Tuesday. That authority came from a law the Washington State Legislature passed this spring granting local jurisdictions 0.1% sales tax authority for creating housing affordable to households below 60% of area median income. Executive Constantine envisioned using the revenue for extremely low-income housing (less than 30% area median income).

However, suburban city councilmembers had other ideas and preferred to control the funding themselves and dedicate it toward higher income levels–housing much less likely to serve homeless people directly. Since the authority is only for 0.1% sales tax, the cities have blocked the county measure from applying in their jurisdictions by passing their own measure first before the County acted. These city-level efforts will contribute to affordable housing creation as dictated by law, but in a less coordinated way and at the expense of the County plan.

Erica Barnett laid out the implications in her excellent coverage of the fracas.

“But how much money will there be? The county originally estimated that the tax would bring in a little under $68 million in 2021; bonding against half that revenue stream, the maximum allowed under state law, could give the county around $400 million to purchase sites and turn them into affordable housing,” Barnett wrote. “The cities that have opted out of the tax so far have taken more than $8 million off the table. That brings the county’s annual revenues down to just under $60 million.”

With the additional cities opting out hitting eight, an estimated $18 million has been carved out of the measure. The County will have have to downsize its ambitions since the full $400 million in bonds won’t be possible initially after eight cities jumped ship and went their own way. Beyond obstructing the County’s plan to build 2,000 units of supportive housing, these eight cities have cast doubts on the regional approach to homelessness services that was supposed to be getting underway about now.

Suburbs deny their role in homelessness

As I pointed out in December when Seattle rushed to joined the regional homelessness authority and foot most of the bill, the suburbs had no skin in the game and were promising very little. What Seattle stood to gain wasn’t clear then. And so far the regional authority is off to an inauspicious start, and it’s not just this latest kerfuffle; the authority still lacks an executive director after a consultant-driven talent search took longer than planned.

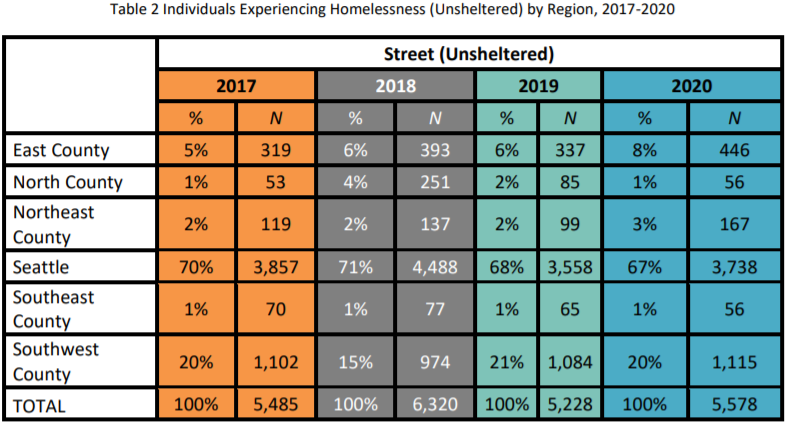

Annual one night counts show the issue of homelessness touches the entire county and the number of homeless people continues to stubbornly climb, approaching 12,000 in January–even before the pandemic tanked our economy and wiped out tons of jobs. The 2020 count showed Seattle shelters 4,428 of the county’s 6,173 sheltered homeless population–72% of the sheltered population.

Unsheltered homelessness is more diffuse. 20% is in Southwest King County–home to cities that are opting out of the tax: Renton and Kent. On the bright side, Tukwila voted to stay in the countywide measure in a 5-2 city council vote, with leaders like Councilmember De’Sean Quinn speaking up for regional partnership and the need for supportive housing. Similarly, Federal Way considered but rejected a go-it-alone proposal. Meanwhile, the count tallied 8% of the unsheltered population in the Eastside, where Bellevue and Issaquah are going their own way.

The Bellevue City Council’s deliberations, which Urbanist reporter Christopher Randels live-tweeted, revealed conflicting desires in suburban leaders. They want the regional homelessness authority to work and to partner with it without actually ceding authority or contributing funds to it. They don’t want to do the taxing themselves, but they’re all to happy to spend the revenue when somebody else takes the initiative. They want to help homeless people, yet they actually target their housing investments at higher income levels and push responsibility for supportive housing–which experts believe is key to solving homelessness–and other services to other jurisdictions.

The suburban cities seem to be denying the reasons the regional authority was created in the first place. Instead of coordinating their investments on the regional level to make them more efficient and avoid redundancies, they’re insisting on planning their affordable housing investment at the city level, eating into city staff time, diluting bonding capacity, and throwing away the chance at close regional coordination.

The United States Census Bureau pegged the median housing income in Bellevue at $112,283–in Maple Valley it’s $107,299, and in Issaquah it’s $101,508. These are 2018 figures, and these numbers have only climbed since. These are wealthy places that have ample resources and a moral obligation to contribute to the homelessness solution. It’s too bad they’re still stuck fighting petty turf wars.

It’s also a shame these cities and the County haven’t done more to address a homelessness crisis years into a declared emergency. Sydney Brownstone’s article in The Seattle Times noted leaders on homelessness worried the pull out of the countywide measure meant these cities weren’t serious about proven solutions.

Alison Eisinger, executive director of the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, said she worried that cities pulling out of the tax signaled a lack of support for homelessness interventions like permanent supportive housing.

“I hope sincerely that some of this is politics rather than policy, and that some cities are trying to make a statement and position themselves for negotiating purposes rather than opting out of doing this good, big necessary thing,” Eisinger said.

“My concern is that there are certain electeds who are not bought in to the clear, understood, effective solution,” Eisinger said. “So that means we just have more work to do.”

Need for countywide progressive taxation

Seattle isn’t exactly a paragon of decisiveness here either, but the Emerald City does invest more than its neighbors. That became doubly true after Seattle City Council recently passed the JumpStart Seattle payroll tax on large companies to raise $214 million annually. That dwarfs the proposed countywide measure three times over.

Instead of passing their own payroll taxes on major corporations, Seattle suburban neighbors seem to be salivating at the opportunity to swipe those jobs from Seattle as tax havens. If the region had all been rowing in the same direction toward progressive taxation to fund progressive priorities, a countywide sales tax hike may not have been necessary. But now we’re stuck relying again on the sales tax, which does fall much harder on the poor than say a progressive income tax.

A sales tax that exceeds 10% with no income tax, no capital gains tax, and a payroll tax only in Seattle isn’t how a progressive region would set up a tax system. Yet it’s the system we’re stuck with for now. It certainly makes addressing our homelessness crisis a lot more difficult. And until suburban cities buy in, it’s likely an impossible task.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Federal Way had passed a city-level sales tax measure to opt out of the county homelessness measure. The Federal Way City Council in fact rejected that proposal. However, North Bend, Covington, and Snoqualmie had been added in light of the fact that they passed measures, giving a new total of eight. A quote from Alison Eisinger has also been added and the updated math with the additional desertions.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.

ドイツキ (@Deutski1)

ドイツキ (@Deutski1)