Last week, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) opened its newest bridge to general purpose vehicle traffic after two years of construction. The South Lander Street Bridge in SoDo separates vehicles, pedestrians, and people biking from the railway tracks between 4th Ave S and 1st Ave S at a cost of approximately $100 million dollars. It includes four vehicle travel lanes and one 14-foot separated pedestrian and bicycle path on the north side of the bridge.

Since Seattle has a goal of reducing passenger vehicle emissions by 82% within the next decade, this will likely be the last time that the city is able to invest that much money in keeping vehicle traffic moving by creating a new bridge, rather than investing in decarbonizing its transportation system. The opening of Lander Street comes at a time when much attention is being drawn to the condition of Seattle’s current bridge inventory, and the fate of the currently-closed West Seattle freeway bridge is very much up in the air.

The Lander bridge will provide a lot of benefits, with the most significant safety-related. There have been at least three pedestrians struck and killed by train traffic at the previously at-grade crossing in the last decade. Grade-separation should make the street safer for everyone. In addition, the bridge will save Metro buses that connect to SoDo station, and people walking, biking and rolling, from having to wait for train traffic which is given priority.

But the question of whether those benefits are worth the $100 million investment in a four-lane overpass still remains as the city grapples with its huge transportation funding deficit and Mayor Jenny Durkan cuts bike and pedestrian safety projects citywide yet again. Seattle’s penchant for putting mega-projects before maintaining basic access for people walking, rolling, and biking must come to an end.

Completing the grade-separation of Lander Street has been a goal of freight advocates for approximately 20 years. Funding for the overpass was included in the predecessor of the Move Seattle transportation levy, Bridging the Gap. But another mega-project, the Mercer Street redesign, had escalating project costs in the late 2000s–funding from Lander was diverted away. The overpass was included as part of the $6.9 billion in road projects tied with Sound Transit 2 in the Roads and Transit ballot measure in 2007, but after that measure was defeated in part for environmental concerns, it languished. The 2015 Move Seattle levy included $20 million of the then-estimated $140 million project cost.

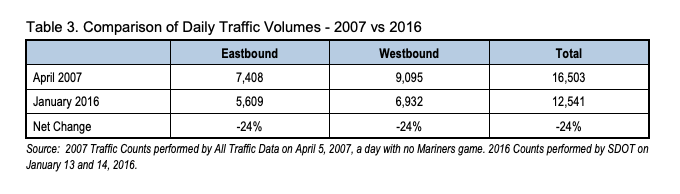

But when the Move Seattle levy passed, and the city prepared to submit an application for Federal dollars, a traffic study had not been completed on Lander since 2008. The 2016 traffic study showed that volumes on Lander were actually down by nearly 25%–only around 12,500 cars a day were using the street, down from 16,000. But when Senator Maria Cantwell announced the awarding of the $45 million FASTLANE grant, the press release contended that “current congestion at Lander Street costs the Washington economy $9.5 million per day or $3.4 billion a year”–an outlandish claim for a street that was recorded as having as much traffic as a busy neighborhood arterial. But here vehicle traffic is literally valued more than other types of traffic.

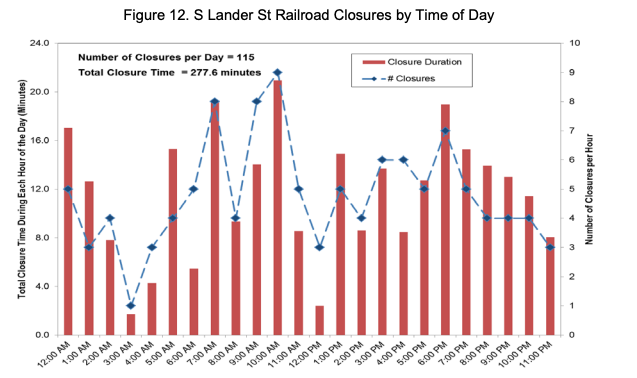

Last week, SDOT’s blog post about the opening of Lander Street boasted of the environmental improvements that will come from the project: “Say goodbye to over 4.5 hours of idling vehicles each day along S Lander St!” This is true, there were 4.5 hours of total railroad gate closures, on average, per day during the study period in 2016. This includes an average of about 17 minutes at midnight, and 20 minutes at 10 a.m., etc.

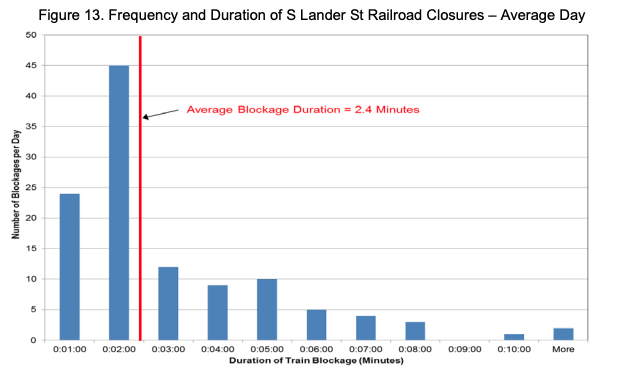

What this also means is that there were over nineteen hours a day that traffic was not halted by the railroad traffic, which is more than you can say for your local neighborhood street light. And yet we recognize that grade-separating intersections to keep traffic moving would encourage more traffic. The average amount of closure time was just over two minutes. This doesn’t tell us how many vehicles were waiting on average per closure. But if railroad closures were generating a high amount of idling vehicles, measures could have been implemented to reduce idling, such as signs instructing drivers to turn off their engines while waiting.

It remains to be seen just how much traffic will use the new four-lane bridge, given the other bottlenecks in the traffic system particularly right now with the West Seattle freeway bridge out of commission.

The Lander overpass actually ended up being less expensive than we had thought it would be in 2015, with some over the funding being returned and reallocated to projects like the RapidRide G line on Madison Street. This is good news. But the overpass itself represents the latest in a long line of projects that trounced significant investments in moving people in our city, not cars. Just as the Lander overpass opens and its connectivity for people riding bikes is touted, the City announces that it has put an extension of the SoDo trail on hold, which would have connected all the way south to Spokane Street.

The previous at-grade railroad crossing was an impediment to freight mobility and transit reliability. But the 2016 traffic study showed that only 8% of all traffic using Lander during the course of an entire day were buses or freight trucks. The new bridge doesn’t include freight or bus-only lanes–the large majority of the vehicles that use this bridge will not be moving significant amounts of freight. Too often freight mobility translates to simply moving more cars of all kinds, which is the opposite of well established city goals which we’re running out of time on. Searching for an all-of-the-above transportation solution is setting us up for failure.

With such a pressing need to invest in multimodal transportation and tough decisions about so much of our 20th century automobile infrastructure to replace, we need to view the Lander overpass as an example of the last-of-its kind, and orient our sights away from megaprojects like it.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.