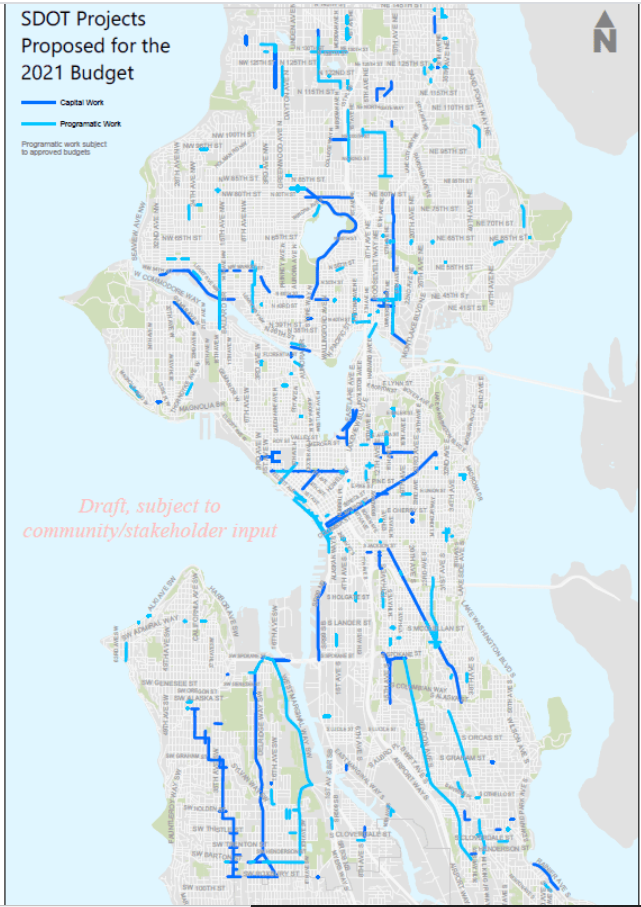

On Tuesday, Mayor Jenny Durkan unveiled her 2021 budget proposal. With no new revenue proposed, the Mayor balanced the budget by draining the City’s emergency fund and cutting spending; transportation was one of the hardest hit areas. The proposal slashed $21.5 million for bike, pedestrian, and road safety projects.

High profile projects like “Thomas Street Redefined” and the Center City Streetcar, which included a First Avenue street rebuild with sidewalk and crossing improvements, remain paused indefinitely. Also cut are numerous smaller projects across the city intended to make it safer and easier for people to get around without a car. Inexplicably, the Mayor’s budget cut the Georgetown to Downtown bike route, despite the need for safe bike routes to Southwest Seattle being more urgent than ever.

Seattle voters have indicated time and again they want to invest in transportation and alternatives to cars–and transit in particular. The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) budget is greatly supplemented by 2015’s Move Seattle Levy, which raises $930 million over nine years with portions set aside for bike, pedestrian, and transit projects. This money is relatively stable since property tax levies–unlike sales tax proceeds–remain steady during recessions like the one we’re in now. Instead of using this steady stream of levy funding to weather the financial storm, the Mayor is squeezing SDOT’s multimodal budget for money.

The Move Seattle campaign pledged seven bus corridors would be upgraded to “RapidRide+”, but in 2018, the Durkan administration scaled back that pledge to four corridors on delayed timelines and downgraded Routes 40, 44, and 48 to lesser improvements. SDOT’s presentation to the modal advisory boards this morning suggest those 40, 44, and 48 upgrades will be scaled back further. Rainier Rapidride R is also unfunded beyond the patchwork of bus lanes under construction (including a stretch from Kenny to Henderson Street.

The Urbanist and the rest of the Move All Seattle Sustainably (MASS) Coalition had advocated for bus lanes on these corridors, even if RapidRide conversion is delayed. SDOT’s Route 44 plan did include significant stretches of bus lanes, responding to this advocacy. That plan appears in jeopardy. Route 40 upgrades were less far along and even more in jeopardy, while Route 48 has barely started the outreach process, and it has just $2 million budgeted in SDOT’s proposed 2021-2026 Capital Investment Program (CIP). Additionally, SDOT announced a plan to shorten the Roosevelt Rapidride J project so that it would no longer reach Roosevelt, instead terminating at U District Station. SDOT is still hoping for a 2024 opening for the J.

Refusal to cut SPD in real terms

There were some obvious alternatives. An unprecedented public uprising that saw upwards tens of thousands in the streets demanding racial justice, an end to police brutality, and specifically urging her to reduce the budget of the Seattle Police Department (SPD) and invest in Black communities. Decriminalize Seattle and King County Equity Now, which represent a huge swath of Seattle Black-led organizations and their allies, asked for a 50% cut to SPD–$200 million. Even the more moderate group Black Lives Matter Seattle and King County asked for a $100 million SPD cut.

Instead, the Mayor refused to cut SPD in real terms.

Civilianizing parking enforcement and emergency call center operations offloaded about $15 million and $22 million, respectively. With that shifting around of costs, SPD’s proposed $360 million 2021 budget hardly represents a cut. The 2020 budget ended up around $400 million after a rebalancing package of cuts that the Mayor also opposed for cutting SPD too deeply. Counting the $37 million shifted to other agencies, the 2021 police budget still sits around $400 million. After four months of protests, the Mayor hasn’t budged. The Mayor budgets for 1400 sworn police officers–which only amounts to losing about 20 existing positions through attrition.

What’s in SDOT’s budget

Despite significant cuts, SDOT is also making big investments in the next few years. One of the big ticket items was unanticipated. The West Seattle Bridge catapulted into SDOT’s plan after extensive cracks formed in concrete in the high bridge’s center span, forcing the agency to close the relatively young 36-year-old bridge in March due to the risk of collapse.

The agency has completed some temporarily shoring work and mercifully the bridge hasn’t collapsed into the Duwamish River. However, the bridge needs more repair work before it can open to traffic. The Mayor’s budget proposes borrowing $100 million to fund this shoring and repair work, but even that may not be enough. SDOT believes repairs can extend the bridge’s life another 15 years, but they are going to weigh that option against a full replacement.

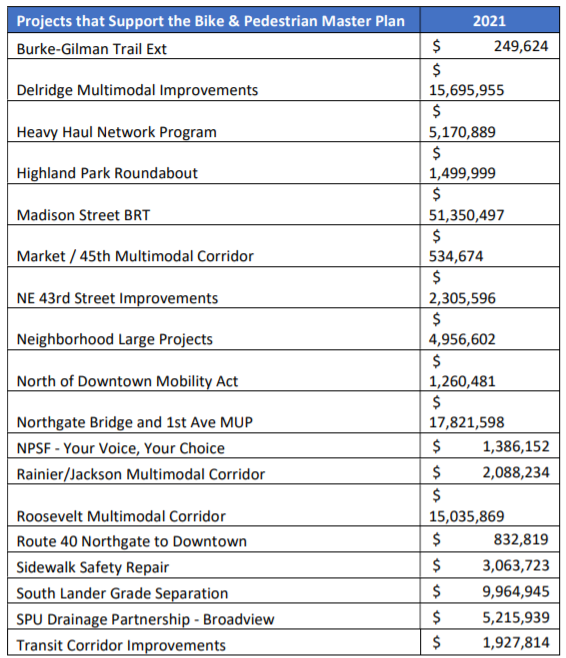

The biggest items under the bike and pedestrian bucket are $51.4 million for the Madison Street RapidRide G project, $17.8 million send aside for Northgate Pedestrian Bridge, $15.7 million for Delridge RapidRide H, and $15 million for upgrades on the Roosevelt Multimodal Corridor–hopefully including Eastlake Avenue bike lanes. It appears RapidRide H is on track for a 2022 opening, while RapidRide G is currently scheduled to open until 2024.

Other big expenses in SDOT’s budget include the Alaskan Way Boulevard rebuild that is happening in and near the footprint of the torn down Alaskan Way Viaduct and Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), which are adding adaptive signals on Denny Way at a cost of about $7 million. Though criticized by the likes of us, that adaptive signals item is staying in because otherwise SDOT would lose federal grants funding the effort–and because the Seattle Center Arena’s transportation plan is predicated on flushing a lot of cars from the arena–and not very ambitious about walking and biking goals.

SDOT also stressed the progress it has continued to make amidst the challenges the pandemic and recession presented in a blog post earlier this week.

“In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Department has continued to deliver in every way possible, while facing competing priorities born of the pandemic, the West Seattle High-Rise Bridge closure, and limited staff resources as many high-risk individuals were unable to perform their normal duties,” SDOT’s Katie Olsen wrote. “These successes can be seen across town, with the soon-to-be open Lander Street Overpass, the significant progress on the Northgate Pedestrian/Bike Bridge and the Fairview Ave Bridge Replacement, Safety and transit improvements on Rainier Ave S, new sidewalks and pavement on N 40th and N 50th Streets as part of the Green Lake and Wallingford Paving and Multimodal Improvements, and NE Pacific St next to UW Medical Hospital, the completion of seismic retrofit work on the Cowen Park Bridge and similar efforts on the Howe Street Bridge wrapping up this winter, the start of construction on the Delridge RapidRide H corridor, clearing Federal readiness requirements on the Madison BRT project, and the recent construction of the first phase of a 4th Avenue PBL, just to name a few.”

Impact of I-976

The budget does not assume that the Seattle Transportation Benefit District (STBD) will be renewed, which funds about 15% of the Seattle’s bus service. That measure expires at the end of the year and the Seattle City Council put it up for renewal in the November ballot. If the ballot measure passes, SDOT will have more funding to invest in transit service, infrastructure upgrades, and last-mile “new mobility” services.

Due to the passage of Initiative 976, car tab fees are off the table–at least until the State Supreme Court rules on the constitutionality of the Tim Eyman written ballot language. The STBD on the ballot relies on a 0.15% sales tax–50% larger tax that the existing measure–but still pulls in less overall due to loss of Seattle’s $60 car tab fee. Mayor Durkan had proposed a smaller 0.1% sales tax backed measure until the Council, and particularly Councilmember Tammy Morales (District 2), intervened to boost the measure and avert worse transit cuts.

SDOT’s budget presentation

The Seattle City Council is taking its first close look at the transportation budget at the budget committee session 2pm Friday October 2nd (video here). We hoped to learn more at that hearing about exactly what’s being cut and how Councilmembers are reacting to that.

Transportation Chair Alex Pedersen (District 4) got the first word and he voiced his support and said the West Seattle Bridge should be the priority. “SDOT is off to a solid and sensible start,” he said.

Other councilmembers, particularly Morales, expressed their dismay that so many bicycle, pedestrian, and transit projects had been shelved or scaled back. The Bicycle Master Plan and Pedestrian Master Plan had already faced considerable delays and it’s beginning to seem like a pattern, Morales added.

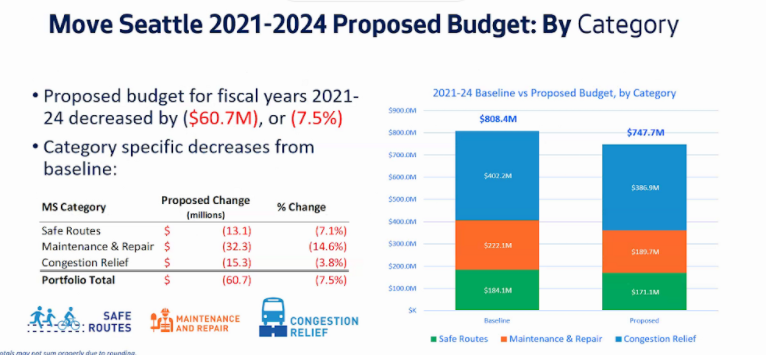

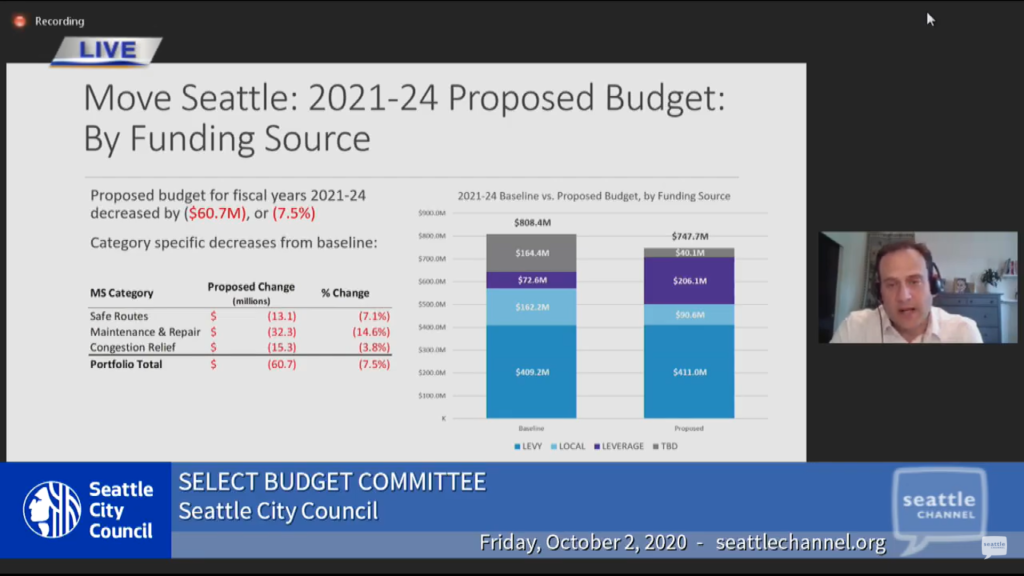

Budget Chair Teresa Mosqueda, meanwhile, flagged the big $70 million drop in local matching funds to Move Seattle Levy portfolio. She asked if this was a policy choice, and SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe didn’t really address the question head on–more or less restating what their plan and not acknowledging the existence of any other options.

Move Seattle Levy funds are holding steady–property tax levies are relatively durable even in a recession–and proposed budget projection even shows slightly higher revenue than the baseline. However, SDOT’s budget shows a sharp decrease in “local match” from $162.2 million in the baseline to $90.6 million in the proposed budget.

One major source of that local match is Real Estate Excise Tax (REET) funds, and those had dipped amid the recession. The Mayor’s budget sets aside some future REET proceeds to pay back the extensive bonding she intends to do to fund West Seattle Bridge repairs. In other words, Chair Pedersen is getting his wish: the West Seattle Freeway is taking a bite out of bike, pedestrian, and transit projects he sees as more frivolous.

This is a developing story. I added the I-976 context at 2:22pm Friday and details from SDOT’s budget presentation at 2pm Saturday.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.