How much should Seattle spend on bridge maintenance and where should the money come from?

People often think of Seattle as a city of hills, but it is also a city of bridges. The recent transportation problems related to the emergency closure of the West Seattle High Bridge have highlighted that fact, as has a recent report put forth by the City Auditor which shows that Seattle has not been spending enough on the maintenance of its bridges. The report said many of Seattle’s bridges are approaching, or have already past, their design lives.

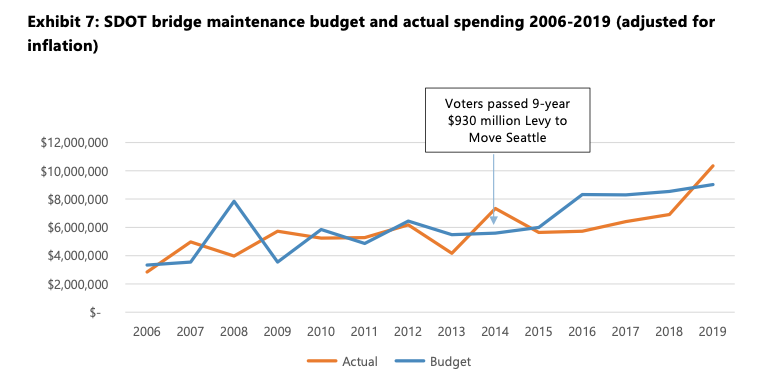

Since 2006, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has been spending about $6.6 million annually on bridge maintenance, an amount that falls far short of the $34 million the agency has projected it needs to spend–at a minimum–to adequately maintain its bridges, which do not include state-owned bridges like the I-5 Ship Canal bridge.

SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe has pledged to increase funding for bridge maintenance; however, he has also acknowledged that it will take years to arrive at the $34 million target number. “We’re facing a ton of resource challenges across everything we do,” Zimbabwe said in an interview quoted by The Seattle Times. “I do think there’s a discussion we have to have as a city–what we do or do not fund. There’s also an urgent need to decarbonize our transportation system.”

In a letter responding to the the City Auditor’s report, Zimbabwe pointed out that the problems that led to closure of the West Seattle High Bridge did not result from a lack of bridge maintenance. “In fact and to the contrary, these critical issues were identified and quickly addressed as a result of existing, proactive thorough bridge inspection program,” Zimbabwe wrote.

And to be fair, the West Seattle Bridge is just 36 years old and not at the end of its designed lifespan–theoretically anyway.

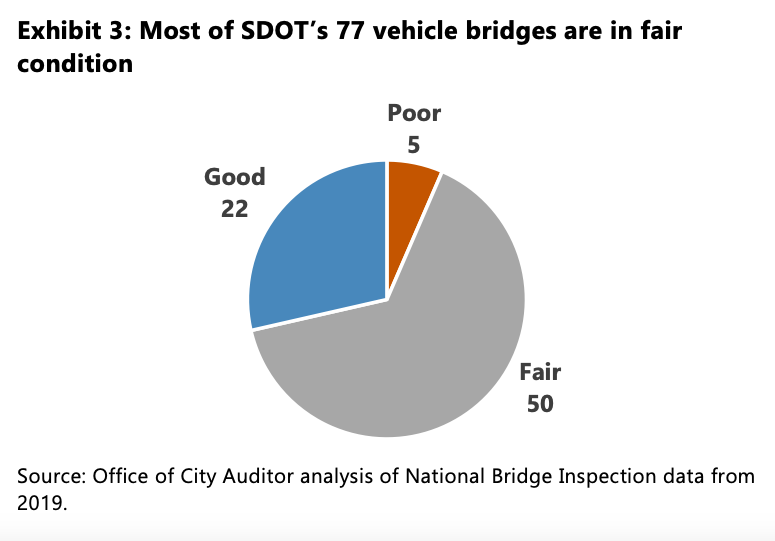

However, that statement did not keep some West Seattleites from calling foul. One commentator on the West Seattle Blog wrote that Zimbabwe’s comment was “so absurd it actually made me laugh out loud.” Another commentator, responding to the fact that the majority of Seattle’s bridges, including the West Seattle Bridge, have been rated as “fair,” stated, “In other words, the vast majority of bridges are in the same state as the West Seattle Bridge. How reassuring. Is there a qualified adult in charge of any department within the City of Seattle?”

The Seattle Times Editorial Board was also quick to lodge accusations, claiming that the report’s findings indicated that SDOT had “shortchanged” bridge maintenance in order to increase investment in bus and bike lanes, and also “fancy new things like costly streetcars and foot rests for bicyclists downtown.”

It’s not surprising how quickly the knives came out. Seattle faces a lot of transportation infrastructure challenges; whether it is missing or non-ADA accessible sidewalks, potholed streets, or aging bridges, almost everyone in Seattle has something to complain about when it comes to the topic of transportation infrastructure. But is it fair to say that SDOT has been skimping on bridge maintenance in order to foot the bill for other less critical investments? Where Seattleites’ opinions fall on that debate will likely color people’s responses to the question, but beyond that schism there are circumstances that complicate the entire situation around funding Seattle’s aging bridges.

Critics have been quick to call out SDOT for failing to spend its full bridge maintenance allowance. While it is true that SDOT has not always spent all of the money it has been allocated annually for bridge maintenance, since 2006, SDOT has spent 93% of bridge maintenance funds. The agency said fluctuations in bridge maintenance spending can be attributed to the fact that “budget [does] not always align with actual expenditures on a year-by-year basis.” In some years, SDOT has had to carry over funds to spend on major projects in the following year, while in other cases, such as the spending dip of 2016-2018, the agency reported that a lack of staffing–and thus maintenance work–resulted in reduced costs.

But other questions remain to be answered. For instance, how did SDOT arrive at a point where it has routinely requested tens of millions of dollars less in funding annually than it estimates is necessary to cover bridge maintenance expenses?

A staggering backlog of bridge maintenance expenses

For many years now, SDOT has found itself between a rock and a hard place when it comes to infrastructure funding.

Back in 2013, Erica C. Barnett reported for Seattle Met that the cost of the maintenance backlog on Seattle’s roads and bridges was approaching to $2 billion. The $2 billion figure was taken from an SDOT report which claimed that the City should be spending $190 million on road and bridge maintenance annually, rather than the $40 million to $50 million it had been spending.

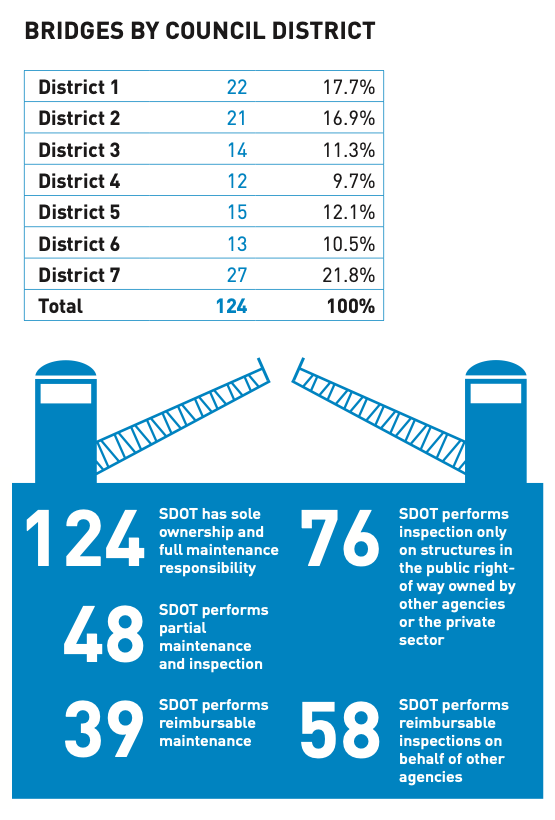

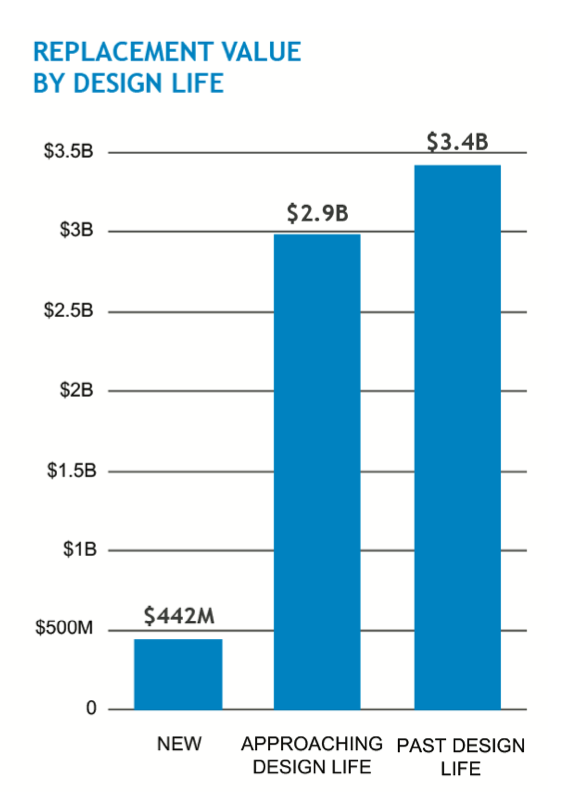

As dismal as those seven-year old figures appear, today’s reality might be bleaker. According to the City Auditor’s report, the cumulative replacement value of Seattle’s bridges which are either approaching or past their design lives is approximately $6.3 billion. To put that figure in context, Seattle’s entire operating budget is about $6.6 billion annually.

How did Seattle get to this point? For one thing, it is important to point out that just because a piece of infrastructure is approaching or past its design life does not mean that it is automatically unsafe. SDOT completes safety routine checks on all bridges, and has publicly stated that all of its bridges are safe for people to travel on. This has allowed for the agency to buy additional time for raising funds.

Like transportation agencies across the nation, a lot of SDOT’s decision-making rests on how much funding it has and the source of that funding. Funding for current services and new projects alike often include multiple sources–the City general fund, state grants, federal grants, funding raised by levies and other taxes–the list can go on and on. Determining what projects have the highest likelihood of attaining sufficient funding to move forward is a delicate and ongoing dance undertaken by SDOT. Sadly like other cities across the United States, the agency has lost an essential partner.

Ever since the federally funded infrastructure boom of the 1950s, state and local governments have hoped for the federal government to step up its funding for transportation infrastructure, but those hopes have all too often failed to materialize into actual investments. For the last 30 years, nearly three quarters of transportation infrastructure spending has been paid for by state and local governments, a trend that seems unlikely to change soon. SDOT Director Zimbabwe referenced the problems related to decreased federal funding in his response letter to the City Auditor’s report, citing how federal funding for transportation has fallen from 1% of gross domestic product (GDP) to 0.5% of GDP over the last 35 years.

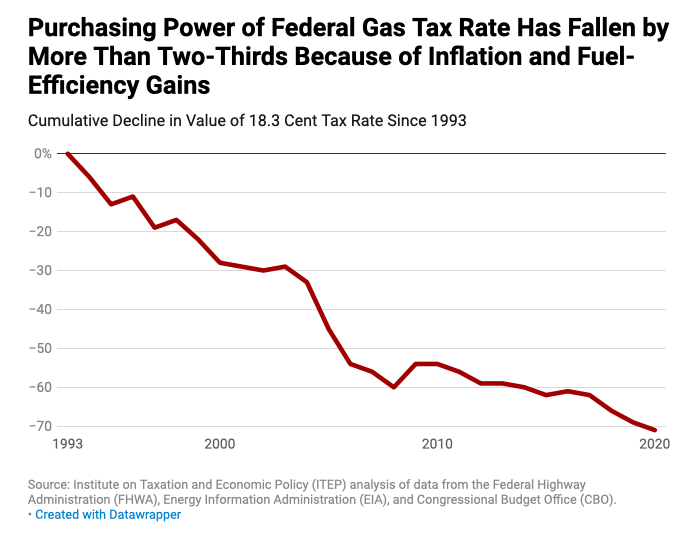

Most federal funding for transportation comes from the gas tax, which has remained at 18.3 cents a gallon since 1993. Additionally, inflation and improved vehicle efficiency have also decreased the amount of funds raised by the federal gas tax; the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITP) estimates that the gas tax would need to be raised to 62.2 cents per gallon to regain its 1993 purchasing power.

Zimbabwe also identified lack of state funding as an issue, one he attributes to the the Washington State having “many infrastructure needs to address across the entire state.” But these infrastructure needs are not unique to Washington, according to an analysis of United States Department of Transportation’s 2019 National Bridge Inventory (NBI) database, more than a third of all US bridges (37%) need major repair work or should be replaced. So even if the federal government were to change course on the topic, the sheer amount of backlog would make it difficult for any city or state struggling with aging bridges to pin its hopes on salvation through federal funding.

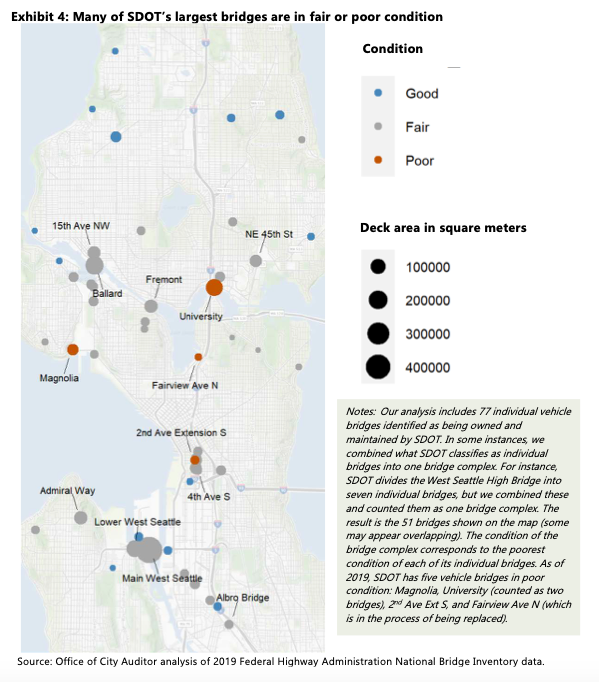

On the local level, the NBI database statistics translate into two of Seattle most heavily used bridges, the University Bridge, which carries about 30,000 vehicles daily, and Magnolia Bridge, which carries about 20,000 vehicles daily, at least pre-Covid. Both of which have been rated as “poor” according to United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) guidelines.

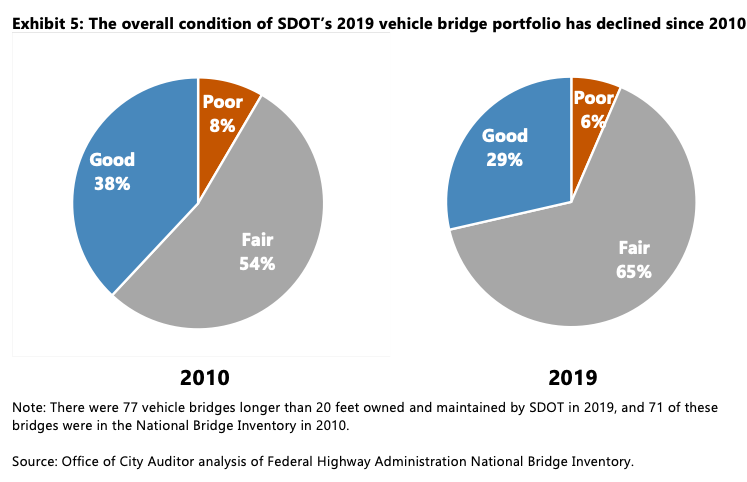

Given lack of federal and state funding, why have local governments failed to step up to cover the expenses? The issue seems to lay with voters’ dislike of new taxes and large spending measures. Back in 2006, City officials walked back the initial proposal for the Bridging the Gap levy, which would have resulted in a 20-year, $1.1 billion property tax, which critics had labeled a “never-ending tax.” The Bridging the Gap levy approved by voters that same year was scaled back to nine-year, $365 million property tax, a decision which served to shortchange investment in Seattle’s aging bridges which has reaped real consequences; according to the City Auditor’s report the overall condition of Seattle’s bridges has declined in the last decade.

What about the voter approved nine-year $930 million Move Seattle levy that followed Bridging the Gap? The larger levy did pour more money into SDOT’s coffers, and the Seattle Times Editorial Board has taken issue to the fact that the amount of funding designated for road and bridge maintenance decreased from 67% in the Bridging the Gap levy to 45% in the Move Seattle levy.

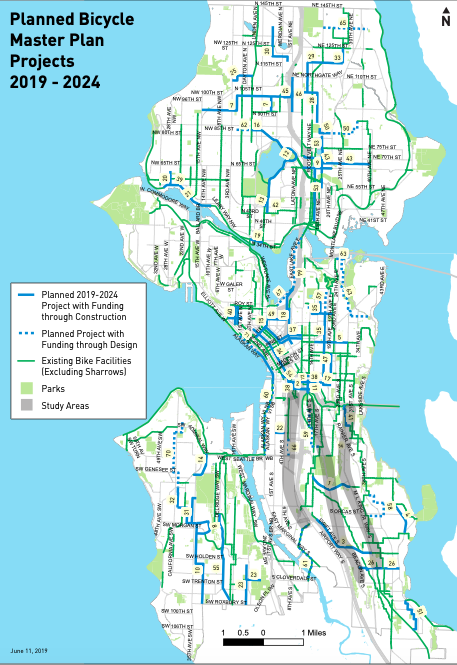

However, when you compare the amount dedicated to bridge maintenance in the Move Seattle levy to other expenditures, the argument becomes more difficult to uphold. In the current Move Seattle levy, the budget for bridge maintenance, seismic improvements, and planning and design is $108 million with an additional $27.3 million is funding the replacement of the Fairview Avenue N bridge in Eastlake. Now these numbers fall short of what SDOT has said it needs to fund bridge maintenance, but when compared to other items included in the levy they remain substantial. For instance, the entire Bicycle Master Plan has $63.9 million earmarked from the nine-year levy. It is more challenging to parse out the exact amount dedicated to bus lanes, since bus lanes fall into the wide-ranging category of multi-modal improvements, but the entire multi-modal improvement budget in the Move Seattle levy is $105.3 million, still less than what was designated for bridge maintenance.

Some would argue that scrapping the Bicycle Master Plan and scaling back multi-modal improvements in order to fund more bridge maintenance and repair work would have made for smarter investments. But while bridges play an important role in Seattle’s transportation infrastructure, there are other key players to consider as well. For instance, Seattle’s growing population has made a measurable impact on transportation throughout the city, creating congestion and straining existing infrastructure. Investments in transit have made it possible to reduce congestion, provide more people affordable transportation options, and decrease carbon emissions. Fewer cars on the road also tends to mean less frequent road maintenance is needed.

Take a moment and imagine what Seattle would be like today if, instead of investing in transit, the City had opted to pour all of those funds into bridge maintenance. Congestion, air quality, and social equity would all be worse–and the bridges would still be past their design lives, with the notable exception of the West Seattle High Bridge, which was supposed to have lasted for a couple more decades.

Now critics could argue that even if investments in transit are crucial, funding the Bicycle Master Plan is not because it caters to the relatively small number of Seattleites who bike and roll for transportation. Yet when you consider that the entire Bicycle Master Plan was awarded about half of what bridge maintenance was, the argument begins to lose steam. The distribution is wider, too; the Bicycle Master Plan includes projects across all of the city. Data shows that the number of Seattleites commute by bike and transit has grown over the last decade, in no small part because of improvements made to the city. Halting investment in transit and bicycle facilities could serve to slow down–or even reverse–the progress that has been made.

The Seattle Times Editorial Board has also continued to lance criticism at the Center City Connector streetcar for sucking away funds from bridge maintenance, but the Center City streetcar has been put on pause since the summer, making their point arguably a red herring. Additionally, a large part of funding for the streetcar extension was supposed to come a 51-cent ridehailing tax which also was intended to raise funds for affordable housing. Due to that Covid pandemic, ridehailing trips cratered, drying up the expected revenue since a million-ride threshold had been included to trigger the tax, which Uber and Lyft no longer met.

Pausing the Center City streetcar saved a few million in the current biennium, but that money quickly went to plug other SDOT budget holes the recession had created. Funding from the tax was redistributed to other transit expenses. It is possible that those funds could be moved to fund bridge maintenance, but those changes would also come at a cost.

No easy bridge maintenance funding answers, but a few ideas to consider

The fiscal challenges SDOT faces are clear. So what are some possible solutions? How can SDOT attain its goal of investing $34 million plus in maintenance–and eventually replacement–for its aging bridges without removing funds from investments intended to decarbonize Seattle’s transportation network and propel the city toward a greener and more equitable future?

A new levy aimed specifically at funding bridges is one possibility. The levy could be raised before the expiration of the current Move Seattle levy in 2024, or it could be wrapped into the new 2024 transportation levy. But this approach has its weaknesses. Even with the specter of the cracked West Seattle High bridge looming large in Seattleites’ minds, voters might not opt to pass it with today’s challenging economic climate potentially dooming a large levy from the start. Additionally, given what we know about the deterioration of Seattle’s aging bridges, waiting until 2024 would be both potentially unwise and expensive because of inflation.

Councilmember Alex Pedersen (District 4), who requested the bridge maintenance audit, has presented developer paid impact fees as one potential source of revenue. Impact fees have been a hot topic in Seattle for some time, and the City has waged a longstanding battle against developers who have challenged transportation impact fees using the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) appeals system. The City Council may vote on transportation impact fees this fall, so this is one topic to be on the lookout for updates in the near future.

Tolling and congestion charges have also been mentioned as possible sources of revenue. Currently the City has paused work on congestion pricing after the publication of an initial report on how it might be implemented. Decreased Downtown traffic resulting from Covid-related commute changes makes it unlikely that Downtown congestion pricing will picked up again in the near future, but other tolling options, including tolling bridges, might present opportunities for revenue gains. Engineering firm WSP published a report on the potential for tolling and congestion pricing to recoup some of the transportation funding losses incurred by the Covid recession, arguing that “the use of tolling is tested and proven: the public is willing to pay for value delivered. Likewise, public opinion regarding existing toll roads throughout the U.S. has remained high for a critical reason: U.S. toll agencies continuously make noticeable, meaningful improvements with the net revenues they collect.”

But the greatest potential might be found at the state level. In an editorial for The Seattle Times, Jessica Koski, state policy coordinator for the Washington BlueGreen Alliance, Susan Balbas, board chair of the nonprofit Front and Centered, and Alex Hudson, executive director of Transportation Choices Coalition, presented some ideas for increasing transportation revenue in Washington State which could be applied to raising funds for bridge maintenance and replacement. These ideas included an air quality surcharge, road usage charge, and a luxury transportation tax, all of which could be implemented at the local level, but would be most effective at the state level. Given the importance of Seattle and its infrastructure to the state economy there is a strong case to be made that increasing funding for Seattle’s bridges should be a statewide priority.

But as Seattleites consider all of these points, it is important to continue to weigh how investing aging bridges will or won’t move the needle forward to creating the transportation system that will best serve the city in the future. While it is important to maintain a safe and reliable transportation system today, over-investing in maintaining and replacing aging infrastructure that never served Seattle that well to begin could doom the city to repeat the mistakes of the past.

As The Urbanist Editorial Board argued, downsizing Seattle bridges and focusing precious asphalt on transit, biking, and wider sidewalks could prevent the next maintenance backlog from forming while also finally decreasing transportation emissions and pollution in the city.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.