Former Mayor Mike McGinn contends Monitor Merrick Bobb’s top-down approach doomed Seattle’s police reform efforts from the start–long before SPD’s recent fall from grace over its violent response to protests.

“The SPD is at its nadir,” court-appointed Seattle Police Department (SPD) monitor Merrick Bobb wrote in his resignation letter, which blamed a failed response to recent protests for derailing the police reform effort he led–otherwise characterized as masterful. Former Mayor Mike McGinn sees it differently: “If it’s a nadir like said Merrick Bobb, he’s the one who built the luge run to it.”

Merrick Bobb served as the SPD Monitor for seven years before stepping down this month. Bobb’s parting letter details what he sees as his police reform successes, the obstacles that remain, and even storm clouds ahead. Bobb criticized both SPD’s brutal crowd control tactic versus protesters, and a Seattle City Council’s meddling. He saw the City Council’s pledge to defund SPD by 50%, and strict chemical weapons ban as counterproductive and overreaching.

Bobb complimented federal Judge Richard Jones for enacting a carefully tailored temporary chemical weapon prohibition–in contrast to the City Council’s more sweeping ban.

McGinn asked why, eight years into the Consent Decree, SPD didn’t have better crowd control and de-escalation tactics that would have prepared them for a summer of protests. Instead of preparation, we saw a department determined to teach protesters a lesson. SPD blew through its stockpile of pepper spray and blast balls and casually turned to copious amount of tear gas. Children, journalists, legal observers, and medics were pepper sprayed, blast balled, and tear gassed; many received serious injuries.

“Merrick Bobb has had the greatest influence on SPD policy and operations over the past eight years than any other person,” McGinn said. “Since he was appointed, we have had five different mayors, the City Council’s nine members have completely turned over and there have been seven police chiefs. And police reform is not succeeding.”

We shouldn’t need court orders to stop police from brutalizing Black Lives Matter protesters. It should be standard practice for SPD to prevent unnecessary violence. Instead, by brutalizing people protesting police brutality, SPD has proven their critics’ point. Even a sympathetic observer in Bobb admits, “[T]he SPD set itself up for criticism.”

While generally gushing praises on SPD officers for enacting reform, Bobb did have some criticism for the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG), which represents more than 1,300 sworn officers. He didn’t connect the dots that those commendable officers have elected leadership that have fought that reform.

SPOG has only gotten more resistant to change during the Consent Decree process. Alycia Ramirez laid out SPOG’s radical rightward drift in a recent South Seattle Emerald article. SPOG decisively elected a hard-line president in Mike Solan early in February 2020 who essentially ran on tear gassing, punishing protesters, and tamping down on Leftists.

“When you bend to the mob, we lose as a society, we lose as a nation,” Solan said in an interview with KIRO radio’s Dori Monson show. “Seattle and Portland are the epicenter of far-left progressive socialism and neo-Marxist ideology. This is all about November’s election and police are caught in the middle.”

With an outlook like that, it does seem that Black Lives Matters protests have gotten harsher treatment than right-wing protests or religious demonstrations.

“The consent decree process is failing,” McGinn said. “When you have SPD putting on music to amp themselves up for protesters, covering up their badges, not going into the CHOP when people are hurt, abandoning the East Precinct…”

While Bobb paints himself as the hero of the Consent Decree process and insinuates McGinn was one of its villains, former Mayor Mike McGinn’s story sharply contradicts that. Obviously both men want to paint themselves as strong reformers on the right side of history, but Dominic Holden’s account of events gives some credence to McGinn’s, as he titled one piece: “How Mayor Ed Murray Unraveled Two Years of Police Reform in Only Two Months.” While Holden paints McGinn as “feckless” on reform, he grants progress did happen and Murray actively undermined it in his first year.

Monitor Bobb appears to have done little as Murray weakened accountability measures, and in fact credits Murray as a reformer.

“Unquestionably, Mayor Murray had the best of intentions and helped the SPD to achieve substantial compliance. He thus realized one of the principal goals of his administration,” Bobb wrote.

Praise for Murray seems to be a reflection of Bobb’s high esteem for Police Chief Kathleen O’Toole, who Murray appointed in 2014 and who served in the role for three years. In contrast, he paints McGinn as “hostile” and “strongly opposed” to him–Bobb started his role as Court Monitor in April 2013 during McGinn’s final year in office.

“Indeed, it is notable that the Team achieved reform within five years from then, given the intensity of the opposition the Team faced during the first two,” Bobb wrote. “We had a hostile mayor and an angry, resentful police department run tightly by a small coterie of men who had worked together for years to thwart reform.”

McGinn isn’t shy in his criticism of Bobb, either. “Bobb is always the smartest guy in the room in his estimation.” McGinn said Bobb wasn’t on his list of candidates for Monitor because he worried about his willingness to collaborate with community advocates and commitment to a strong role for the Community Policing Commission (CPC). When the DOJ, City Attorney Pete Holmes, and the Seattle City Council by an 8-1 vote insisted on Bobb, McGinn said he ultimately bowed to their wishes.

Early days of Seattle’s Consent Decree

The sparring between Bobb and McGinn reflects that both played major roles in the consent decree and had different philosophies about it. McGinn also seems to have earned Bobb’s ire when his administration questioned his invoices which included some personal expenses not officially approved for City reimbursement. Bobb pulled in about $50,000 per month, McGinn said. Bobb noted in his farewell that the Egyptian sheets (for which he took some flack) were purchased at Costco.

McGinn was elected Mayor in 2009 and took office in January 2010. A chain of events starting in McGinn’s first year in office set the Consent Decree in motion:

- August 2010: A Seattle police officer murdered Indigenous woodcarver John T. Williams for carrying his pocketknife. The officer escaped charges, and a public outcry ensued.

- December 2010: Thirty-five community organizations banded together and sent a letter to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and U.S. Attorney Jenny Durkan urging them to investigate a pattern of excessive force and racial bias by the SPD.

- December 2011: The DOJ completed its investigation and confirmed the pattern of excessive force and racial bias.

- July 2012: The City of Seattle and DOJ entered in a Consent Decree settlement.

- January 2013: Mayor McGinn appointed 15 members of Community Policing Commission (CPC).

- November 2013: Ed Murray defeated Mike McGinn in mayoral election. Murray ran with backing of SPOG and simultaneously painted McGinn as weak on police reform.

- December 2013: Murray tried to replace interim Police Chief Jim Pugel, but is told he must wait until he’s in office.

- January 2013: Murray came into office, demoted Chief Pugel and other reform-minded senior staff, and appointed former SPOG vice president Harry Bailey interim Police Chief. Bailey dropped disciplinary cases against several officers accused of misconduct.

- April 2014: CPC issues recommendations to tighten up police accountability measures, which Murray had weakened.

- November 2015: CPC urges Merrick Bobb to advance accountability legislation, over which he claimed to have veto power.

- June 2016: CPC asked SPD to suspend use of blast balls, citing serious injuries and their misuse by police for crowd control purposes at Black Lives Matter protests.

- May 2017: Seattle City Council unanimously passed an accountability law, formalizing civilian oversight and making the CPC a permanent commission.

- November 2017: Jenny Durkan wins election with a tough on crime platform while also brandishing her role in police reform.

- November 2018: Mayor Durkan negotiated and signed a union contract with SPOG that undid some of the 2017 accountability measures and boosted officer pay.

- May 2020: Mayor Durkan motioned to terminate the Consent Decree.

- June 2020: Mayor Durkan backtracks and said she doesn’t want to end the Consent Decree after protests ramp up following George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police and a brutal police response to those protests.

The timeline makes clear that the Consent Decree was a slow process. Election-year politics interrupted fledgling momentum. For example, Mayor Ed Murray came into office and insisted on demoting a pro-reform Chief Jim Pugel and putting in a SPOG-picked candidate–Harry Bailey–on an interim basis. While Pugel had demoted command staff that were flagged by Monitor Bobb for not cooperating on reform, Bailey promoted the demoted back up again and forced reformers Pugel and Assistant Chief Michael Sanford into retirement. Bailey was Seattle’s first Black police chief–granted on an interim basis–but he stonewalled efforts to reform the department.

“There’s a reason SPOG spent money on Ed not me,” McGinn said. “The interim chief I appointed, Pugel, did not reduce discipline on officers when requested. So, they supported Ed. Ed was elected. Ed demoted Pugel and then approved reductions of discipline on officers, as well as new uniforms and new cars and probably a pay raise he then realized he couldn’t do. That was the deal.”

Bobb glossed over that part of the saga, satisfied that Murray selected Chief O’Toole six months later to resume reform efforts and undo the damage his interim chief had done. In fact, Bobb did not mention Bailey and called Carmen Best Seattle’s “first African American Chief,” seeming to erase Bailey entirely. Best was the first Black female chief and first Black chief on a permanent basis–nonetheless her reform bonafides aren’t much better and seemed to have been a red flag during the selection process.

McGinn does not shy away from this chapter: “I think this Consent Decree process went south when Ed cleaned out the department of reformers.”

Murray’s administration was supposedly dedicated to seeing through police reform, but that certainly seems a false start. Meanwhile, CPC efforts to appeal to Monitor Bobb to speed up accountability measures seems to have been brushed aside. Attempts to go through other channels–such getting SPD to voluntarily improve its accountability system–didn’t work.

It was the Seattle City Council that pushed forward a new accountability law in 2017–five years after Seattle officially entered into the Consent Decree with the DOJ. Even then, Seattle took a big step backward the next year when Mayor Jenny Durkan negotiated and signed a police contract that stripped out accountability measures and failed to address issues with overtime and cost controls.

Why didn’t the Consent Decree curb police brutality?

The looming question is how successful could the Consent Decree have been given the turmoil and violence this summer? While Bobb argued it was a temporary setback, others have argued the protests exposed that the Consent Decree didn’t work.

To McGinn, the stumbling block is the refusal to share power and the insistence of consolidating it in a few hands that springboard to higher office or the next high-paid gig. Bobb’s letter belies a strong preference for solutions coming from the judiciary rather than the legislative process and the social justice movement.

There should be an outpouring of Seattle gratitude to federal Judge Richard Jones, who, upon an extraordinarily powerful showing by plaintiffs represented exceptionally ably by David Perez, established fair and meaningful rules of engagement for less-lethal weaponry during the protests, and to federal Judge James Robart, who at a critical time did not allow a misguided City Council ordinance to deprive the SPD of the use of less-lethal weaponry under the rules established by Judge Jones.

A final word about the endless squabbling at the top of Seattle leadership: As Rodney King said, “Can we all just get along?” The Mayor, City Council, City Attorney, CPC, and other community groups and organizations must really try to work together and not at cross purposes. I will not miss the endless jockeying and some runaway egos.

The outgoing Monitor seems to see himself as above that jockeying and runaway egos, but in chastising the Defund coalition and repurposing a Rodney King quote to argue for some bland compromise he proves otherwise. Bobb seems to agree with SPD that “less lethal” weapons like blast balls and pepper spray need to be in their crowd control arsenal in order prevent worse violence. That quibbling point repeatedly put protesters and journalists in harm’s way.

Monitor as Shadow Mayor, Durkan as weak Mayor

One of the big concerns McGinn expressed was that the Court Monitor would act as shadow Mayor, hindering how a Mayor could respond to police violence and pressure from communities of color–and that is exactly what has come to pass, he said. McGinn saw that pattern developing as the Monitor and Mayor Murray blew off CPC’s 2014 recommendations to revise crowd control policy to promote deescalation, starting with the suspension of blast ball use.

“It was the first glimmering of the folks in charge using the Consent Decree to thwart progress rather than support it,” he said. “Now under Durkan they’re going to the judge to say they have to be able to use tear gas. They’ve run the Consent Decree upside down. They’re using it to thwart reform.”

Under Mayor Durkan’s interpretation of the Consent Decree, “she has to speak to the judge before protecting protesters from tear gas,” McGinn said.

That’s not the way the system should be set up, McGinn said, and a stronger mayor would refuse to go along and fight the court as necessary.

“The Mayor can say to the police stop using tear gas for crowd control. Period. And accept whatever consequences come from that. The Mayor doesn’t need court approval to protect her own constituents from tear gas,” McGinn said. “She’s a weak mayor. When she says when she can’t control the police, she’s saying she’s a weak mayor.”

Forging a path to police accountability

Mayor McGinn’s approach to police reform wasn’t perfect, but he did get the CPC underway and seems to hold community engagement in higher regard than his successors.

“That’s the fundamental flaw: the consistent minimizing of community input. You have Pete Holmes, Jenny Durkan, and Cathy O’Toole all hostile to the Community Police Commission,” McGinn said. “You have this Kabuki dance among these groups while the problems mount.”

A stronger discipline process with true community oversight remains one of the elusive goals of the Consent Decree. The CPC and other criminal justice have been clamoring for it all along. Washington voters even passed a statewide ballot initiative making it easier to prosecute cops for shootings, but police continue to find loopholes. Moreover, misconduct that should be weeding out violent cops early in their careers before they kill somebody goes unpunished.

Eight years into the Consent Decree, much work remains to be done. SPOG is more diametrically opposed to community oversight than ever. The Mayor says she’s no longer trying to terminate the Consent Decree, and a new Monitor is stepping in.

To replace Merrick Bobb, the City has appointed Harvard professor Antonio Oftelie, but how the decision was made remains murky. Oftelie made his introduction into Seattle with a Crosscut op-ed that largely defended police and criticized and talked past the Defund movement. It seems unlikely the City Council was thrilled about this selection.

Oftelie is determined to look at the bright side with wonky gusto: “The department’s nation-leading improvements include not only microcommunity policing plans, but also new data analytics platforms and records management systems that provide real-time numbers on every police incident and open doors to proactive response and reform. The public should not ignore its massive investment in the police department, which made it otherwise a national leader in de-escalation, analytics and transparency.”

It’s hard to see SPD as an analytics report away from reform success. Given the many false turns, the years of doldrums, the backtracking, and the newly made obstacles, perhaps the question we should be asking ourselves is not how to keep the Consent Decree afloat, but how to build a better boat.

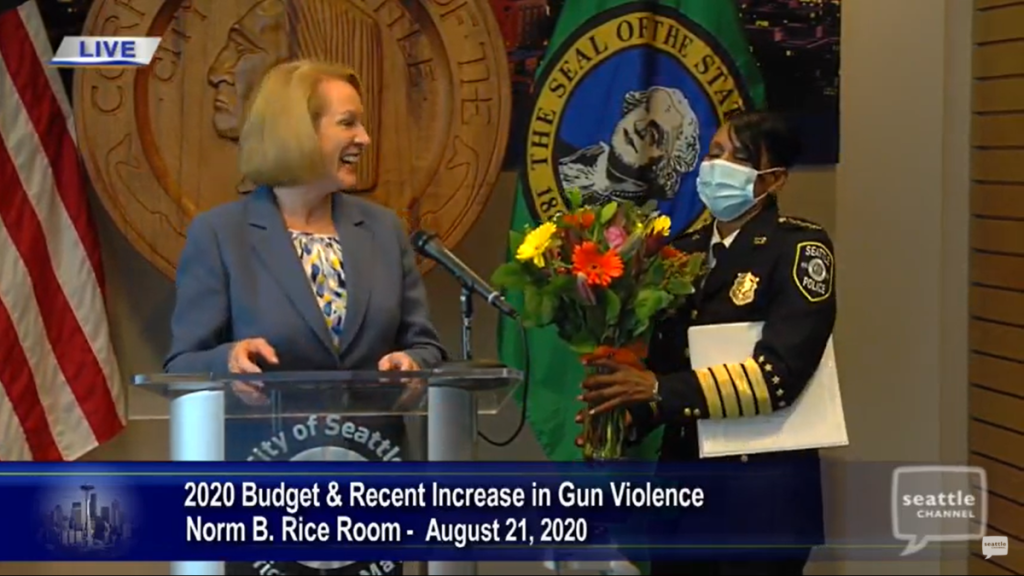

The featured image is by Ethan Campbell.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.