The Unique Urbanism of Disney’s Movie Cities

For those of us who adore movies, seven months of pandemic has been a difficult drought. We’re down half a dozen film festivals and two full seasons of blockbusters, beyond just the weekly joy of sitting in a dark room with dozens of strangers laughing, jumping, or crying together. Though some theaters are reopening, longing for movies is not a big enough draw to be in an enclosed space with other mouthbreathers for three hours. As Anne Hornaday points out in her non-review of the only-in theaters release of Christopher Nolan’s new film, “the symbolic and economic importance of ‘Tenet’ notwithstanding, it simply didn’t feel essential enough to make the cut.”

So if we want to see a new movie, we’re streaming. The leader of that has been, not surprisingly, Disney. Since Onward was released a few weeks into lockdown, Hamilton saved us over the Fourth of July, and the almost watchable Artemis Fowl popped up in-between, The Mouse has provided most novel entertainment this summer. Now we get to see the live action Mulan for a small premium over our Disney+ subscription. Realistically, $30 plus delivery dinner isn’t terrible for a family of four’s evening entertainment.

And it’s pretty good movie. Mulan is richly filmed with a strong female lead and all Asian cast in a remake that originally featured a talking dragon. Mulan’s stoic princess and the wire-fu acrobatics will call for comparisons to Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, but that’s unfair. This is a coming-of-age film, and a good one, not a mystic caper steeped in symbolism. Both movies are two hours long, which felt necessary for Crouching Tiger but is kind of ridiculous here.

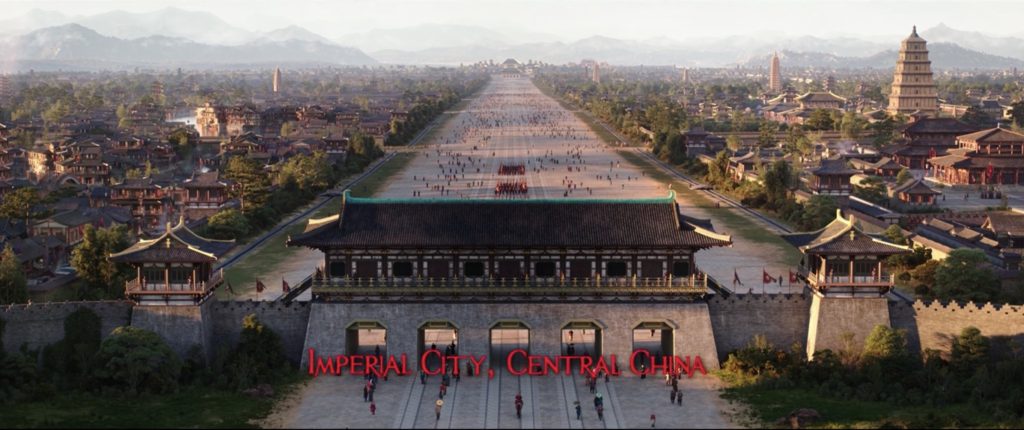

Mulan bookends in the Imperial City of China. Wide shots of the Imperial Palace and temples set up the power of the Emperor (played by Jet Li!) and importance of his dynasty before cutting back to Mulan’s small village. Unfortunately, the plot requires the palace to shrink in the last act to maintain drama. It sells short the power and importance of the location and by extension minimizes the proportions of Mulan’s unlikely success.

But Disney consistently truncates their locations to move along plot. And since we’re so steeped in Disney right now, let’s take a moment to appreciate the kind of cities that appear in Disney films. Many have dove deep into Walt Disney’s obsession with urbanism. From the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT) through the quasi-imperial Reedy Creek Improvement District to the fully planned community of Celebration, Disney has built real cities. Real construction like Main Street in Disney World uses forced perspective to make Main Street look taller, similar to the telescoping Imperial Palace in Mulan. Interestingly, their amusement park shorthand translates into the urban places appearing in their movies.

Three choices.

For those movies that are not journey stories, Disney sets their stories in one of three places.

Most obvious are the Kingdoms. Princesses, by definition, need castles. The battlements and towers, the walls. The studio’s title card is a castle. This allows for a kind of renaissance festival urbanism with ribbons and tiny shops that conveniently ignores cholera and the oppression by feudal rulers.

The modern, non princess movies are usually set in the suburbs. The bully next door in Toy Story and the work-a-day witness protection Mr. Incredible can only inhabit the mundane world of single-family tract housing. Suburbs are the quiet veneer under which toys have rich inner lives or from which a grand new adventure can be launched.

Then there’s The Future. Wide shots of gleaming glass on bright sky. They’re not expansive density. Disney cities are towers in a field, tapering up to a massive central peak. It’s postcard urbanism that allows for a show of prosperity and development and plenty of crevices where plot can happen down on the ground. It also gives a focus to the city, with a main building likely where the Big Bad lives or some plot is going to happen. in a lot of ways, it’s the same kind of structure as a kingdom, just designed in steel.

Trains Go Everywhere

Regardless of the level of density, Disney cities have awesome transit. The trains cross the countryside in just the perfect way to allow a sweeping view of the next location. Fast, efficient, built for moving the plot along. It is the best kind of transportation drama, a breathtaking entrance to a new life without delay.

City!

Some Disney movies are located in real places. The source material puts Peter Pan and Mary Poppins in London. The Rescuers are in New York because of the United Nations. Mulan and Moana aren’t going to take place in Boston. However, the Disney movies that get identified with specific places wear their cities like a jersey with creases.

Ratatouille is in Paris because of the title pun, not because of Paris itself. The location is a shorthand for the best food in the world (as they say in the first lines of the film). But the city is quite empty of people and not a compelling part of the story short of long gazes at the Eiffel Tower. Most of the action happens in the kitchen. The movie’s villain, critic Anton Ego, is so evil he has a British theater accent. (Specifically, Peter O’Toole’s.)

The Princess and The Frog is similarly gilded in New Orleans. The city plays a role as a setting for Tiana’s life and future restaurant, but most of the movie’s action and character development happens out on the bayou. When they return to the city, it’s for Mardi Gras to emphasize the swirl and countdown to midnight. The jazz and the beads are just for show. This is the South, but most of the discussion of segregation is through contrast with Tiana’s rich white friend Charlotte La Bouff. Though the city is deeply Catholic, there’s two preliminary weddings that call into question whether Prince Naveen would even be allowed to marry in St. Louis Cathedral at the end of the film. Also, Louisiana did not permit interracial marriages until 1967.

For these Disney movies, the city is a character, just not an interesting one. The animators got tons of details right without the underlying tensions that make these real places. They’re handsome vacant princes, or World’s Fair culture like all the World Showcase at EPCOT. Important attributes of the city are condensed into a simple-to-understand outline. Paris is snobby about food so let’s make a rat the best chef. New Orleans is southern magic. Skip all the hard personality stuff and head right into the movie plot.

The Exception

There is one Disney movie that broke many of these rules and ended up with a location that was an important character in the film. The city was run down and full of drunkards. The main character stole rides on the streetcars. Though Mickey Mouse actually appears in the movie, many folks forget that it is a Disney film. And the dames weren’t bad, they were just drawn that way. Of course, we are speaking about Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

Eddie Valiant’s Los Angeles feels lived in. He’s moving through a place that has stuff going on outside of him and the primary story line. The guys at the bar were there drinking before Eddie and Roger showed up. The Judge and the Hyenas had swindles going on the side. Benny the Cab has other fares and Marvin Acme has a regular table at Jessica Rabbit’s performance. That personality of a busy, lively Los Angeles comes through in the barely contained mayhem of the movie.

Contrast that with the townspeople in Frozen that we only see walking around to get to a coronation or talking about a coronation or complaining about their uncomfortable coronation suit. In Zootopia there are plenty of animals moving through the train station, but each has a punchline. In a completely reverse Bechdel situation, the boys of Brave only speak in reference to their potential wedding to Merida. No one is just existing in these worlds.

Which is why Roger Rabbit is the optimum vector for the personality of a city. So much Disney is luscious recreations of subjects that imagineers and animators and storytellers have studied and poured over to tease out the tiniest details. But cities are messy and accidental. Roger Rabbit’s velocity and antics are so grand that they need space. So he wasn’t going wild in a blank void, the filmmakers got to decorate the area around Roger with city personality. Other Disney movies may simply be too precise to have this space for developing cities as characters.

In the absence of space to develop places in the story, Disney movie urbanism relies on theme park tricks to convey place. The landmarks. The tropes about regal castles and boring suburbs. The trains literally moving the plot along. Even when they’re not based on a ride, Disney movies masterfully use those same techniques to tell a good story. That’s fine in Summer 2020 because these movies are the closest most of us are getting to an amusement park for a long, long time.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.