As Seattle pored over its police department budget this year, one thing that stuck out like a sore thumb was $30 million in planned overtime worked into the department’s $409 million budget. A City Auditor report revealed rampant abuse and the great cost of the overtime system in 2016, a workgroup report confirmed the issue persisted in 2018, and a recent investigation in The Seattle Times still couldn’t get answers on why the problem had worsened.

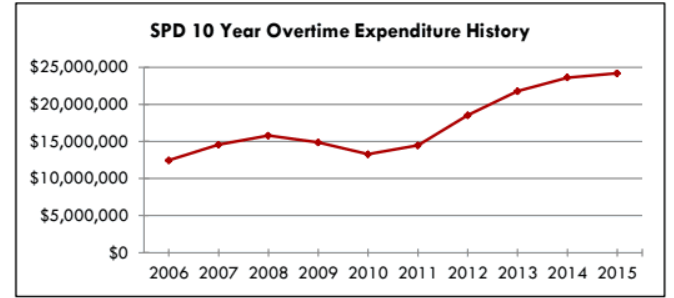

As one might expect, a department with $30 million in planned overtime isn’t exactly careful in how to spend it. That number has escalated out of control over the last 15 years. In 2006, SPD spent about $13 million on overtime, but that has more than doubled since.

The reaction of Mayor Jenny Durkan and the Seattle Police Department (SPD) so far has been to promise imminent improvements to the record-keeping and payroll system. Interim Police Chief Adrian Diaz also announced a plan to shift 100 officers to patrol by pulling them off special units–exactly which ones hasn’t been spelled out.

SPD has claimed the increase in patrol officers will lessen the need for overtime, but that remains unclear. SPD’s move to put detectives back on patrol may end up accelerating attrition if senior officers are not interested in a return to patrol work. Vacant positions would likely increase the need for overtime–at least if SPD refuses to shift its deployment strategy.

Last month, Durkan vetoed the city council’s budget rebalancing package that would have cut 100 officer positions, primarily though attrition. She argued that the cuts were too deep and that the Navigation Team, which conducts homeless sweeps, was essential. The city council may override the veto next week.

The overtime issue exposes the incredibly lopsided terms of the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) contract. Mayor Durkan negotiated and shepherded the current contract through city council in 2018, lavishing on more perks like retroactive pay increases, on-going pay increases, signing bonuses, and so forth.

That contract expires at year’s end. This time, SPOG won’t benefit from MLK County Labor Council membership during this upcoming negotiation. The influential body expelled them in June.

A bad police contract

The terms of SPOG’s contract thwart efforts to ensure accountability and control costs. The contract guarantees:

- Three-hour minimum for any overtime pay, meaning a significant portion of claimed overtime hours were not actually physically worked;

- Standby pay just for being on call;

- Officer allowance to clock up to 90 hours per week–just shy of 13 per day;

- Officer ability to clock up to 12 hours of overtime per day while taking vacation days; and

- Lavish pensions—often six figure compensation that continues into retirement.

Meanwhile, the Seattle Police Department’s (SPD) shoddy accounting practices mean that:

- Overtime pay is tracked in a separate paper system meanwhile standard hours are electronically entered, making it difficult to monitor mistakes or false reporting.

- Timesheet audits are time consuming.

- There’s no automatic system for catching errors.

This is not a new issue, as Seattle Times reporters Daniel Gilbert, Daniel Beekman, and Manuel Villa highlighted in their excellent article on the report.

SPD has struggled for years to monitor its overtime costs, which initially were budgeted at about $30 million this year. The city auditor’s office in 2016 cited numerous lapses in SPD’s policies and procedures governing extra pay, including identifying 400 potential duplicate overtime payments totaling more than $160,000 in 2014. The auditor suggested, and SPD endorsed, an automated system that would flag errors or inappropriate use of overtime.

Four years later, that system is still not in place. SPD says it is expected to go live “within the next year.”

The Seattle Times, September 1, 2020

New technology may not fix much; SPD is already failing to correct even glaring issues. There’re discrepancies over how many hours Ron Morgan Willis–SPD’s highest paid officer at $414,543 in 2019 earnings–actually worked: “Adding to the confusing picture of Willis’ compensation, there are some interdepartmental discrepancies in exactly how many hours Willis was paid for,” the two Daniels and Villa wrote. “While payroll data from human resources shows he was paid for 4,149 hours in one year, records provided by SPD total just 3,874.5 hours.”

In addition to 274.5 hours of pay seeming to be in error, the fact Willis even “worked” around 4,000 hours is stunning when 2,080 hours is a standard full-time work year. Though a full-time patrol officer, Willis is also an adjunct trainer, which would seem to suggest SPD doesn’t have enough training staff or isn’t worried about one officer doing the work of two-full time employees and earning about as much as three would thanks to overtime pay.

Excessive overtime linked to excessive force

While SPD’s excessive use of overtime is a major budgetary issue, it’s also a public safety issue. Research has shown a link between overtime and excessive force complaints. Officer fatigue leads to greater risk for mistakes, much like how research has showed that truck drivers and commercial pilots make more mistakes as they become fatigued over long hours. For police, those slip ups include excessive force incidents–SPD has killed 30 people in the last decade.

SPD has faced criticism for brutality, escalating conflict, and heavy-handed tactics at Black Lives Matter protests. Rather the pull back, the department has insisted on a large presence at demonstrations, which is driving up overtime costs.

To increase public safety and avoid governmental waste, the City’s next budget should reallocate money set aside for overtime to higher uses, and the next police contract should implement stricter caps on hours per week to lessen officer fatigue and the risk of tragic excessive force incidents. The City should also drive what apparently is a hard bargain that police should only be paid for hours they actually work.

We might find that both crime and police misconduct go down when officers employ as much creative energy doing their jobs as they currently do filling out their time sheets.

Clarification: This article has been updated to note the City Auditor report came out in 2016 and recent Seattle Times report had confirmed the findings were still a major issue that hasn’t yet been addressed.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.