I used to see these two often. Neighborhood stalwarts both, who each single-handedly elevated the community. Solomon, from Ethiopia, a fifty-something jolly fellow who wasn’t quite chubby, always with a ready smile, worked in catering, generally for high-end hotels. He had a lot of stories.

Ed was similar in age but thin, even cleaner-cut than the already put-together Solomon, slick in a working-class sort of way. He was black American, and I was pleased to see them chatting easily tonight, bridging the invisible divide that too often separates African and African-American cultures here in the Valley. They were old enough to not care about such things.

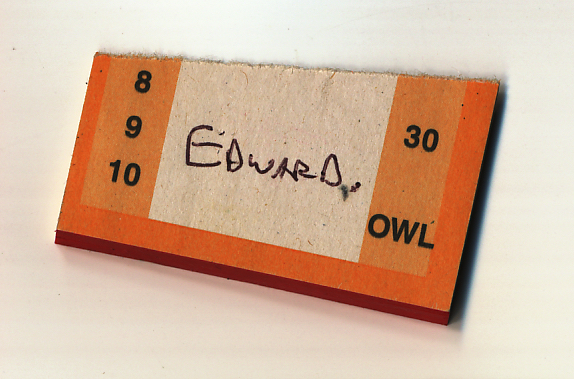

“Sometimes I get up at 4 A.M.,” I heard Solomon saying behind me. They chatted for a while about odd hours and long shifts. Ed finally got up and said, “What’s your name?” Solomon responded in kind and they shook hands. To my surprise he introduced himself to me as well—“I’m Ed,” he said, flashing a movie-star caliber smile.

He then sat down and returned to the conversation. “But you know, we got to be thankful for havin’ a job. Not everybody is so lucky right now.”

“That’s true,” said Solomon. A relaxed vibe colored the air; something not unlike the after-dinner glow, or the pleasing camaraderie of a campfire when you were young, as the older folks spoke together in calming tones.

Ed said, “I’m 54, and my son is 26, great kid, and he gets up at the crack o’ dawn every day to go to work. And he learned to do that by watching me get up at the crack o’ dawn every day to go to work.”

“That’s impressive,” I say, “especially for a youngster.”

“It is. So it’s not always what you say, but what they see—”

“Leadin’ by example—”

“Yeah. I don’t wanna sit here and talk bad about my father, but man, he was not a good example. The way he treated my mom, the amount of time he was ever around… but also, they say if you have bad parents you’re destined to be a bad kid, but that’s not always true. ‘Cause you could be learnin what not to do!”

Solomon: “Yeah. Yeah, we always learn, no matter what’s goin’ on.”

Me: “You’re right, ’cause both my parents come from not exactly ideal family situations, but they’re amazing people. They’re incredible parents.”

“Yeah.”

“I never put that together before. It doesn’t mean you’re destined for failure.”

Solomon again: “‘Cause they could be learnin’ just by watching.”

Solomon got off, shaking hands with Ed again. Ed rode the Prentice loop with me up to his house. He told me a story, as he put it, of his father, who he’d seen only a few times in his entire life, how this father never met Ed’s children or other relatives, though he lived only eight blocks away… the details are a wash. But I remember one thing:

“He came and woke me up one night, shook me awake, he’s standing over me in his military uniform and everything. He says, ‘I’ma see you tomorrow.’ He wasn’t there the next day, or the next. I didn’t see him for thirty years. I never forgot that, him saying he’d see me tomorrow.”

“That keeps me hitting me at the heart,” I said, regarding that incident after he’d moved on to other subjects. “‘Cause that’s one thing I try to never do, is break promises I’ve made to kids. ‘Cause that’s a big deal. I mean it’s a big deal with anyone, but especially with children. They don’t forget stuff like that.”

“Nathan, it was such a pleasure talkin’ to you. If you’re on this line I’ll be seeing you again.”

“I’m here all five days! It’s my favorite route. I rode it a lot as a child, so it feels comfortable in a way for me now.”

“Say what they may about Rainier Beach, but up here…” We marveled at the view of Lake Washington.

“Oh, it’s beautiful up here!”

It pains me that this is my only story with Ed. There were others, but I’ve since misplaced the notes, and the lines we exchanged are lost to time. I’m almost certain he is dead now, because I once came upon him and asked him how he was doing. I don’t need notes to remember what he said to me, over seven years ago:

“Well, Nathan. I’ve had better days, but I’ve also had worse ones.” I asked him to elaborate, and he did. He’d just been diagnosed with a rare bone disease which was terminal, and carried a remaining lifespan best measured in months, not years. I was stunned. Ed, pillar of the community, loved by all? Ed, whose wife and daughters I’d met on the bus more than once, each joy-filled charmers as much as he was?

He’d had worse days than this?

I told him I was in awe of his fortitude and perspective. You’re a big deal in this community, I told him. I want you to know. People talk about you, and it’s only ever good stuff. I hear them all the time.

He happened to have a folder with him, perhaps from the doctor’s visit, which also contained material on his community organizing work—he proudly shared some photo printouts of him leading a rally in the Central District, among other noteworthy items.

I only remember glimpses of the conversations I had with him. How I wish I still had the notes. An evening ride up to the Prentice neighborhood as he told me of a decades-old memory seared in his mind: waking up to his father choking him in rage at night. And Ed telling me how he swore to never let his children feel any such terror, to ensure they would always feel safe and loved by their father, that he would be constant and regular as a loving presence in their lives. He had the knack for turning trauma into a learning opportunity, for stopping the tide of hate with love. People talk about doing that all the time. Most don’t follow through.

A couple months after this I would have trouble recognizing him due to how slowly he moved, grimacing in pain as he bent his knees to sit down. But as ever the resilient glow, despite the physical torment. He’d tell me I brightened his day, and I’d laugh in reply: “Ed, it’s you who’s doin’ the brightening! You make my day!”

Several years later his wife got on my bus. To this day I regret I didn’t ask her when I could about how Ed was doing. I was scared of hearing what likely was the answer. He gave me his number and encouraged me to stop by one of their Sunday family meals, and I cannot tell if my memory of once calling him really happened or if it’s my own desperate wishful thinking. In 2013, I had no experience with Death. Maybe I would have made things worse.

After a time Patricia began deboarding through the rear doors, and I felt for her; she carried a weight too heavy for strangers to make worse by bringing in small talk. The last time we spoke she told me of a venture she was starting up concerning women’s makeup and possibly hair. I mostly remember the anguish we will all eventually feel, the restless and tiring search to rebuild ourselves in the days of After.

Oh, Patricia, if I could talk to you now. Will these words ever cross your desk? You and your daughters remain blessed to carry within you the spirit of such a great man, a man whom I know I am extremely fortunate to have known, even briefly. I hope this recollection does your husband justice. I know I’m not the only one inspired by his memory toward goodness.

As I recently told another passenger: I don’t understand this world, but I like living in it.

I hope you do too.

Nathan Vass is an artist, filmmaker, photographer, and author by day, and a Metro bus driver by night, where his community-building work has been showcased on TED, NPR, The Seattle Times, KING 5 and landed him a spot on Seattle Magazine’s 2018 list of the 35 Most Influential People in Seattle. He has shown in over forty photography shows is also the director of nine films, six of which have shown at festivals, and one of which premiered at Henry Art Gallery. His book, The Lines That Make Us, is a Seattle bestseller and 2019 WA State Book Awards finalist.