It is no secret that working as a ridehailing driver is a precarious business in which the benefits of flexibility can be outweighed by a lack of employee protections and benefits. Even so, it may come as a surprise to many readers that Seattle ridehailing drivers earn on average only $9.73 per hour after expenses, a figure that comes nowhere close to the city’s current minimum wage for contract workers of $16.39. The data on wages comes from a report titled a Minimum Compensation Standard for Seattle TNC Drivers published recently by James Parrott of The New School and Michael Reich of the University of California, Berkeley.

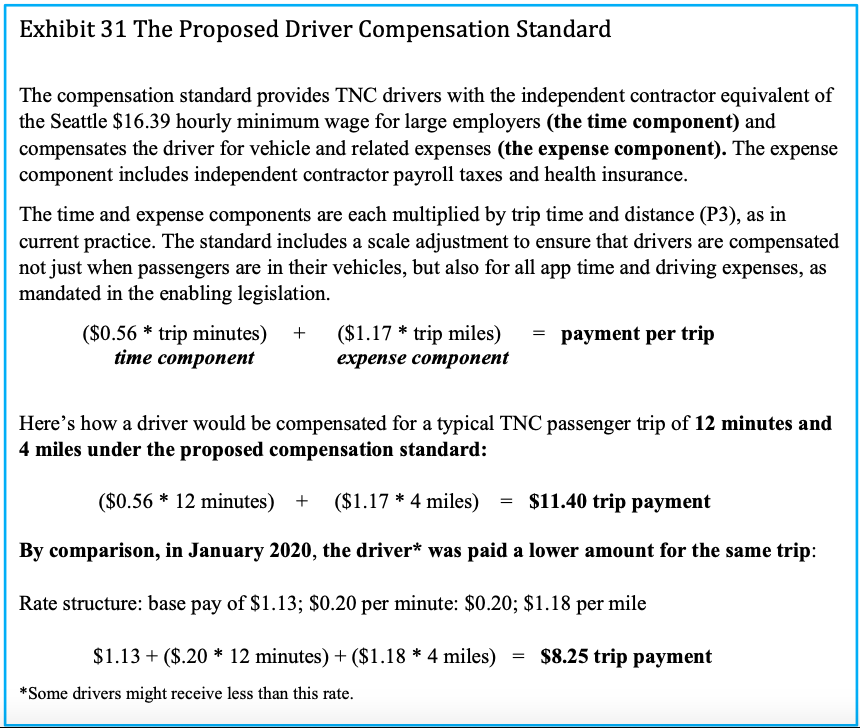

In an effort to boost ridehailing drivers’ earnings to meet the minimum wage, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan has promised send legislation to City Council later this month proposing a new minimum compensation standard for ridehailing drivers. Currently the Mayor is proposing drivers be compensated 56 cents per minute for trip time, plus an expense rate of $1.17 per mile for expenses related to acquiring, maintaining, and operating vehicles used to transport passengers, as well as covering costs for health insurance and mandatory payroll taxes and license fees required of independent contractors.

If the City adopts the proposed minimum compensation standard advocated for by Parrott and Reich, preliminary research shows hourly gross compensation by approximately would increase 30% and increase net hourly pay by more than 60%, raising the wages of approximately 84% of Seattle drivers.

In response to the Mayor’s proposal, the union representing some ridehailing drivers has asked for greater wage protections and issued four demands, including higher per mile compensation, increased transparency on company commissions, increased pay for short trips, and an end to the five-year vehicle age limit for Uber’s Blackcar SUV service.

Ridehailing drivers’ low wages is an equity issue.

Low wages for ridehailing drivers has been a cause of concern for some time. A 2016-2018 King County study found that 24% of ridehailing drivers operating in the county earned wages at or below the federal poverty level, versus only 4% of workers across all professions.

Using data from the same study, Parrott and Reich identified that ridehailing companies were able to expand their services in Seattle by “tapping into a workforce drawn mainly from immigrant males without a four-year college degree.”

[C]ompared to all payroll workers in King County, [rideshare] drivers are much more likely to be male, black, or foreign-born. The differences within each of these demographic categories between drivers and all workers is substantial: 50 percent of drivers are black, compared to only five percent of all workers. Drivers are nearly three times more likely to be immigrants than all King County workers and are more likely to be of prime working age, 25-54, than all workers. Seventy percent of all TNC drivers have less than a four-year college degree compared to 49 percent of all King County wage and salary workers.

A Minimum Compensation Standard for Seattle TNC Drivers, James A. Parrott and Michael Reich, 2020

Access to healthcare coverage is also an issue for ridehailing drivers. 27% of drivers have no health insurance, while 37% have incomes low enough to qualify for Medicaid. The ability to purchase health insurance has taken on increased importance during the pandemic. Outreach completed by the City of Seattle that polled almost 11,000 ridehailing drivers found that many drivers valued higher pay and access to a safety net over the flexibility that current gig economy model is often cited for.

The press release from the Mayor’s Office acknowledged the race and social equity component of taking action to raise driver pay, including a quote by Fana Abreha, an Uber driver and former physician in her native Ethiopia, who cited how she and her husband have to work seven days a week and trade shifts to care for their children in order to make ends meet.

“I hope a fair pay standard will allow us drivers a financial safety net if we get sick or have unexpected expenses, and the freedom to work towards our dream of a better future for our kids,” Abreha said in the press release.

Any increase in driver compensation will likely confront resistance from Uber and Lyft

Based on events unfolding in California, it is all but guaranteed that ridehailing companies will fight back against a minimum compensation standard or even suspend operations in Seattle if such a law comes into effect via a capital strike. In California, Uber and Lyft are seeking to skirt a new California law that would require them to classify their currently “independent contractor” drivers as employees by threatening just such a capital strike and funding a ballot measure called Proposition 22 which the companies are promoting as a “third way” to resolve inequitable work conditions for drivers.

Under Proposition 22, drivers would still be classified as independent contractors, but would be eligible for some added benefits like a minimum wage and access to health insurance. However, in a move that underscores how serious the two companies about keeping labor costs low, Uber and Lyft are also exploring franchise options that could also allow them to maintain their drivers as independent contractors. In the meantime, thousands of Uber and Lyft drivers have been thrown into limbo as both companies vowed to halt all operations in California and then reversed their positions after an emergency stay on Proposition 22 was ordered by the California court of appeals.

Ridehailing drivers who might be worried by such news right take comfort in the fact that in 2016 after ridehailing companies pulled out of Austin, Texas, drivers found new ways to attract and retain customers according to an article for Wired. “Within a couple weeks or so, I started realizing it’s actually better that [Uber and Lyft] are not here,” said Miguel Monsivais, who drove for both companies starting in 2015, but shifted to operating a pedicab for a driver cooperative called Arcade City, which used a Facebook group to connect riders with drivers after the companies pulled out of Austin and continues to operated to this day, despite run-ins with the law stemming from a lack of permits for drivers. “This is our money, and it belongs to us. It belongs to the community,” Monsivais said.

For the most part, changes in Austin did not last long. After only a year, Uber and Lyft were back and the nascent independent ridehailing industry collapsed under the pressure of steep discounts offered by the industry behemoths. Nevertheless, Arcade City, has continued to thrive. Christopher David, the “Mayor of Arcade City” even recently published an open letter to Californian residents, touting the benefits of their peer-to-peer, self-governing driver cooperative in which drivers set their own rates, keep 100% of their fare, and can build a recurring customer base. The group is urging Californians to vote No on Proposition 22 in order to pave the way for a “new cooperative revolution” in ridehailing.

According to Arcade City, some of the accomplishments of their cooperative model include a workforce that includes twice as many female drivers as traditional ridehailing companies and higher wages and job security for drivers. Depending on how things move forward with Mayor Durkan’s proposed minimum compensation standard, Arcade City might be setting its ridehailing expansion sights on Seattle sometime soon.

Correction: This article originally stated that the Mayor’s proposal did not specify a compensation rate for ridehail driver’s additional expenses. It has been updated to reflect an expense mileage rate of $1.17.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.

(@ArcadeCityHall)

(@ArcadeCityHall)