In debating the shape of our cities, the zoning ordinance gets a lot of the headlines. It gives us the bulk and height of buildings, the dimensions of our streetscapes, and the mix of uses in our neighborhoods.

But this emphasis on buildings overlooks the underlying land. Every zoning ordinance is prefaced with the unloved and often unread rules for cutting land into smaller pieces. These rules for “subdivision” are technical and legalistic, causing most folks to glaze over and head to the sexy parts. Such obscurity is a shame because the ignored little sibling etches our planning decisions–good and bad–onto the land.

Now, it is a frequent debate whether owning or renting a home is the smart investment for people. But the reality is that our system conflates homeownership and land ownership. That confusion is enabled by subdivision rules that allow lots to be created fast and cheap. More importantly, subdivision guarantees that this addiction to land will be carried into the future.

Newly completed townhomes in Ballard. These are on lots 19 and 20 of Block 37 on the following subdivisions plats. (Ray Dubicki)

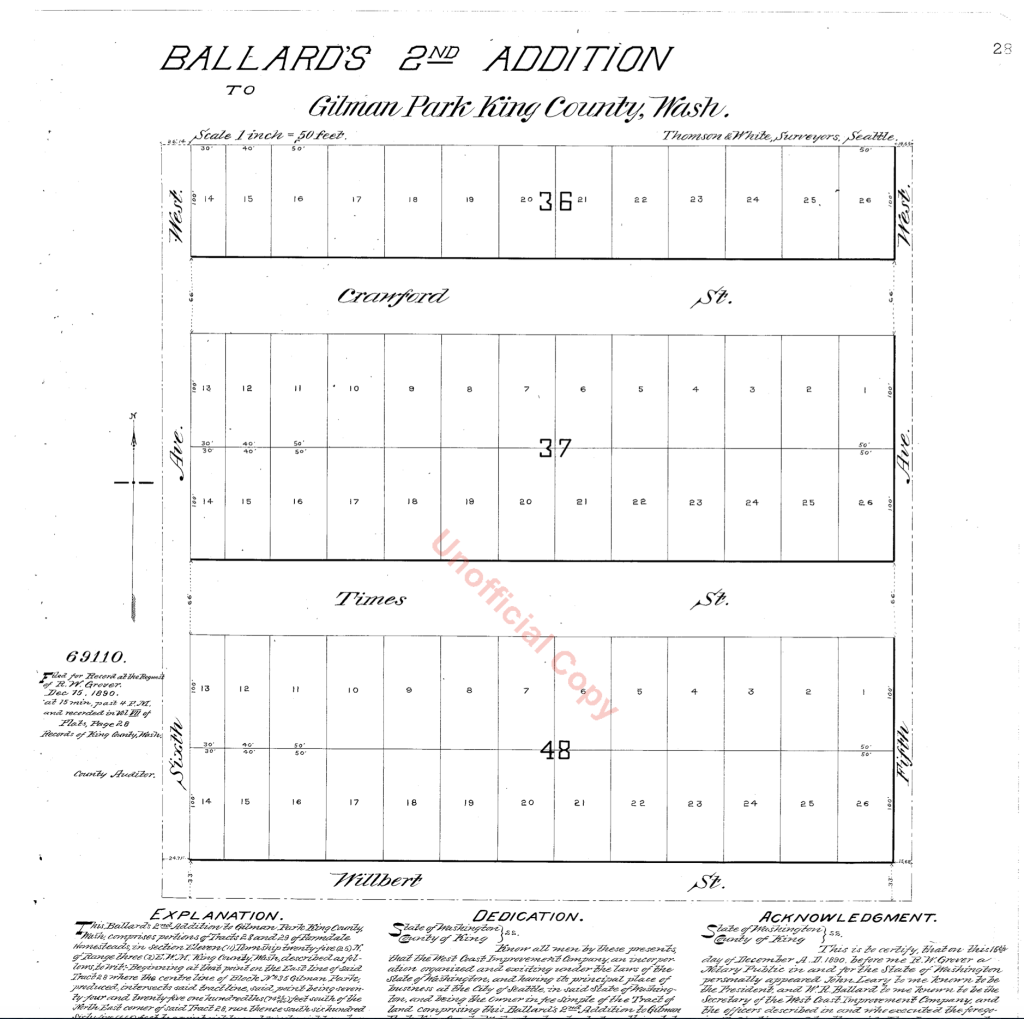

The 1890 subdivision plat establishing lots between 57th and 59th Streets in Ballard. The townhomes in this gallery are at the center of this plat, lots 19 and 20 on Block 37. (King County Assessor’s Office)

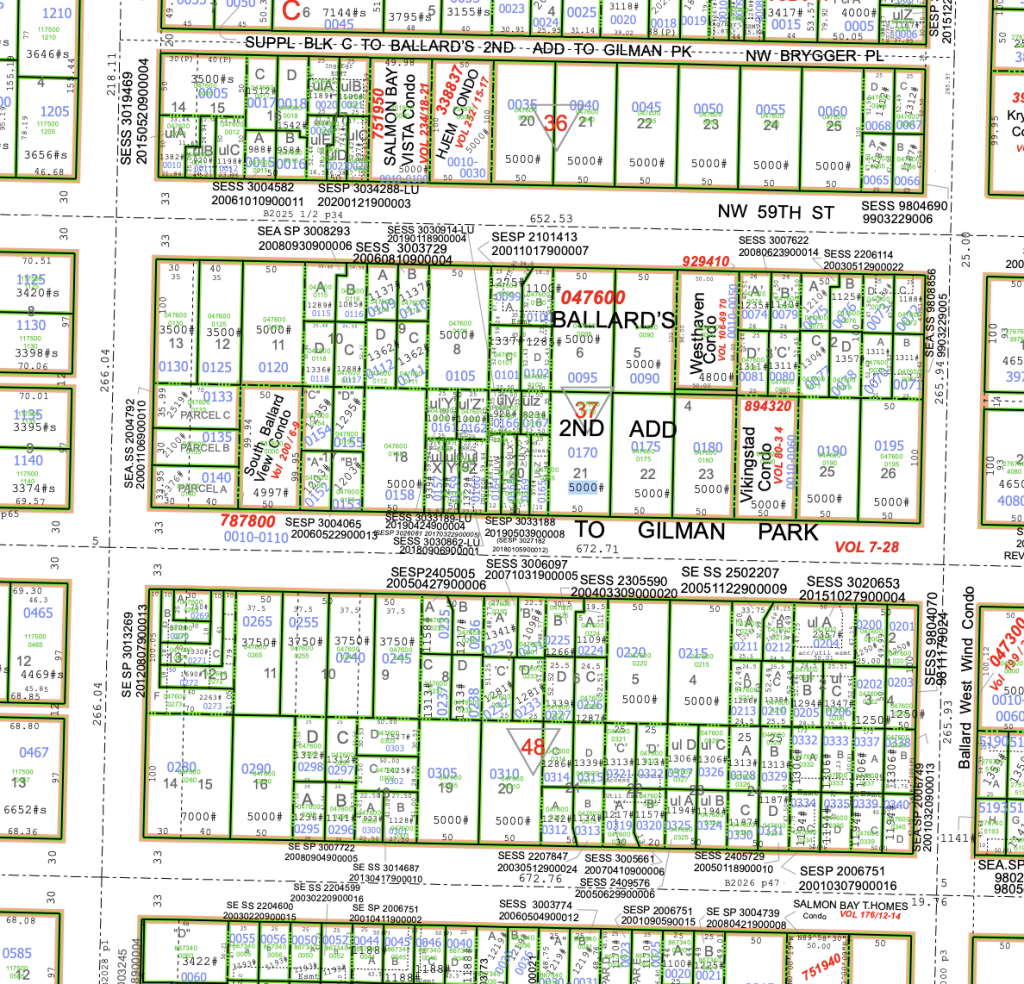

Current state of subdivided lots between 57th and 59th Streets in Ballard. Original lots were quartered for quads. Newer lots are taken smaller for townhomes, such as the 11 lots from two original properties at the center of this plat. (King County Assessor’s Office)

Once a lot is created through subdivision, it never gets unmade. Subdivision leaves a paper trail burdened with the weight of the past and creating a significant barrier to change. That barrier gets higher and higher as we shred city land into the tiniest possible atoms.

The Flattened City

I worked in subdivision for a number of years. The way I came to think about it is that subdivision set up the flat LEGO baseplate which everyone else got to click their blocks onto. Some of the baseplates had roads or ponds that didn’t accept blocks. Subdivision sets the land constraints that changes the shape of your finished building.

While I was not in Seattle, the subdivision process is pretty universal. An applicant wants to cut their property up into sellable lots. They go back and forth with municipal staff about layout, avoiding critical areas and establishing right-of-ways. Staff gets a bunch of reports from other agencies saying if these new lots are going to screw things up. All that goes into a report. There is public notice and a hearing to approve the Preliminary Plat based on some or all of the recommendations of that report. If that passes, a final plat is created that reflects a slew of conditions and legalese.

Subdivision is exciting in the same way as Downton Abbey. It is a vicious bloodbath of fighting and retribution taking place in very austere memos and adjustments of inches. But the ministerial haughtiness of the process belies how life and death the results actually are.

First, when staff forwards the applications to other agencies, they’re not opining on how nice the houses are going to look. The agencies like Seattle Department of Transportation, Public Health, City Light, Housing, Parks and Rec, and the Police and Fire Departments are making adequacy determinations. The departments provide reports saying how the proposed subdivision effects the “health, safety, and general welfare” of the community. This is a term of art for the city’s complete police power.

That police power allows the full force of city authority to be written back onto the plat at subdivision. I had to send out referrals to federal agencies and military bases who then required height limits for flight paths. On the recommendation of geotechnical advisors and environmental staff, we had to exclude certain areas from development because of weak soils or specimen trees. There were limits to development due to line of sight between communications towers and internet cables. This is not zoning that can get a variance. Health, safety, and welfare are to keep buildings from collapsing and out of unsafe areas. All this is set by the agency referrals that come back into staff.

Indelibly Insufficient

More frequently from these agency determinations, the preliminary subdivision approval can make permanent decisions about improvements to nearby roads and utilities. The city can ask for dedications of critical areas, park land, or sidewalk space. Here health, safety, and welfare manifests as safe streets and livable houses.

That doesn’t always translate to the best results because of the disconnect between the incentives and unaffordability of sprawl. In the suburban jurisdiction where I worked, applicants would ask that the required roads be taken over by the county. The county was not accepting new right-of-way, but would not deny the overall subdivision. Instead, it forced the 10 or 12 homes on a single cul-de-sac to set up a homeowners association (HOA) and maintain a road to minimum county width, but not necessarily county specifications.

That same thing is happening in unincorporated areas near Seattle. Subdivisions around Woodinville and Bothell are throwing up homes where everything except the main arterials are shared easements or community property. Since someone has to own the land, it falls to HOAs. It forces HOAs to take on the burden of roads that should be limited to municipalities with taxing authority. Such burden shifting boosts the HOA fees to the exclusion of some homeowners, guarantees the roads are going to be substandard, and sets the HOAs up for failure when these two things don’t match. It also sets up a complete disincentive for a city to annex developments in the future.

Expanding homes on single lots in unincorporated Snohomish County. This is 192nd Place, a private road shown in red on the following plat. (Ray Dubicki)

The separation between public right-of-way and private right-of-way. The driveway apron leads to a sub-standard roadway with sidewalk on a single side. (Ray Dubicki)

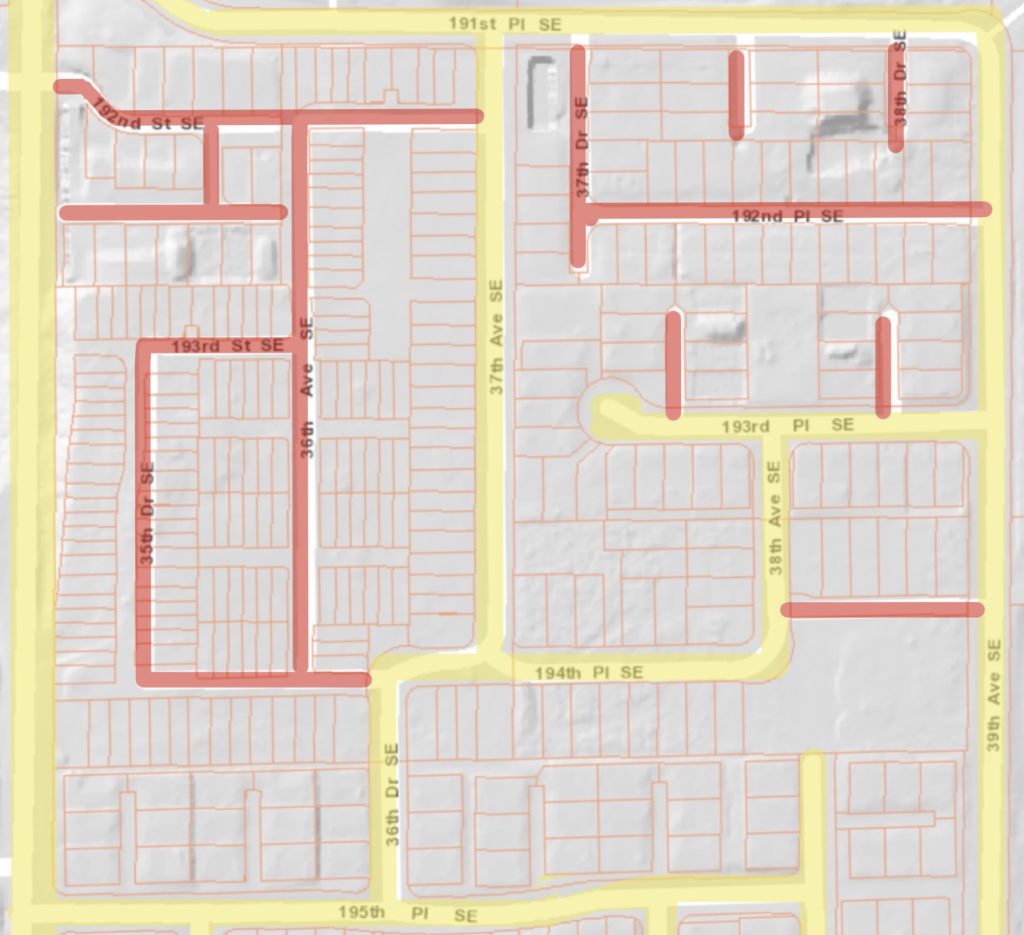

Subdivision layout between 191st Place and 195th Place outside of Bothell. Yellow roads are county maintained. Red roads are private. 192nd Place with the single side sidewalk and double loaded homes is in the top right. (Snohomish Assessor GIS)

It is the decisions at the time of preliminary subdivision approval which set many of these future effects in stone. There is a reason that the building industry refers to the results of subdivision approvals as “entitlements”. They are court enforceable rulings on the intensity of development and limits to what the city is asking for. Builders plug this into their accounting to figure out profit and loss. The jurisdiction’s hands are then tied.

Entitlements are good surety for builders, and totally reasonable expectations on their part. However the property will never be looked at as a whole again. It means that the tests we use today will never be redone to see if they worked. As we question whether measures like level-of-service actually give us safe roads, we cannot go back and reconsider a chunk of development as a whole. Subdivision takes today’s tests, as broken as they may be, and writes them indelibly into the land record by approving a final plat.

Subdivision also establishes access, drainage, and slopes. Easements that determine whether land buildable or unbuildable are set up at subdivision. This is pertinent to how much property tax is collected at golf courses. And even silly things like road names get written on the plat. Try changing a street name to see if it’s permanent.

The Lines and The Lots

This long-term failure from short-term expediency is not limited to public utilities and services. Most egregiously, cheap and easy subdivision throws up invisible walls to density and affordable homes.

The most important clause in any subdivision ordinance is often right at the beginning. In Seattle’s ordinance, Section 23.20.008 states “Lots shall be of a size and dimension and have access adequate to satisfy the requirements of Subtitle III of this title.” Subtitle III is the zoning ordinance. Subdivision reinforces zoning by law.

This may sound acceptable, except our current zoning ordinance puts 75% of Seattle’s land into single-family housing. Subdivision is the amber that crystallizes zoning for future generations. Lot lines for today’s zoning are hard barriers to tomorrow’s density. The problem can be seen in some of Seattle’s most convoluted lots.

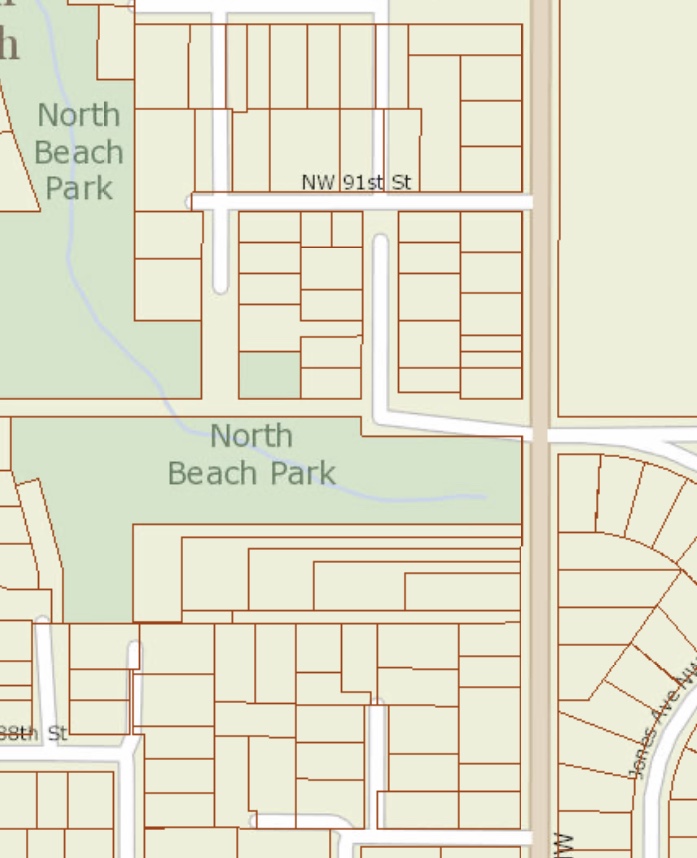

Access is not permitted onto North Beach Park, so stacked “flag lots” have to share a long driveway to access a public road.

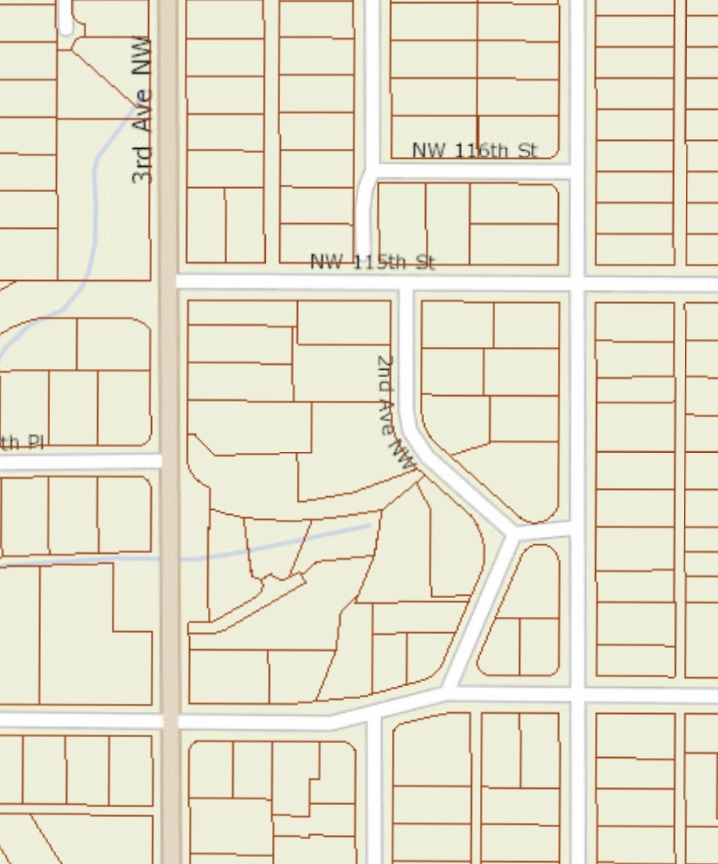

A private driveway and “flag lots” providing needed access for an oversized block along Holman Road.

Lots contort around an environmental feature like a stream, forcing conservation onto private property.

The Eye Of Sauron lot divisions around Haller Lake. Long “flag lots” create easements for access to both roads and water.

A wall of private ownership presents a barrier between Beach Drive and Lake Washington.

Consider that many new townhomes like those at the top of this article are in Seattle’s urban villages where we are supposed to be encouraging density. By attaching individual land to each townhome, subdivision locks that density into the land record. Instead of consolidating, say, four lots to build a larger apartment, there are now a dozen lots to be consolidated. Repeat that atomization over and over for each townhouse development around the city. We are allowing subdivision to shred the city down to 12-foot wide puzzle pieces just because townhomes are preferred in zoning and expedient to build right now.

These lots also show how reversing subdivsion is non-trivial. State law allows vacation of plats. However, vacating a plat that has references or easements to other properties requires approval from those other properties, an enormous problem in these puzzle piece subdivsions. Vacation becomes more convoluted for paper streets and alleys. Occasionally, it also results in howling sexism.

No matter what, every plat or deed bares references to its predecessors. It’s required to prevent “wild deeds” or missing chunks of the chain of title. But it also means that it is virtually impossible to scrub contemporary bad ideas from future parcels. Many current subdivisions are happening inside the lines that existed before. The administrative process is easier for just cutting apart the lots that were already there.

Two existing lots on this corner were further divided into 12 parcels with the main dividing line still evident. The density may be appropriate for now, but the puzzle piece property lines lock that density for the future.

The tolerances for lots are so close that the width of this standard door required space on the plat.

It is the same problem as the racial covenants that exist in so many parts of Seattle. We can say that clauses preventing “persons of Asiatic, African or Negro blood, lineage, or extraction” from purchasing a house are not enforceable, but this text will never be fully expunged from the land record. There will be a deed that references a prior deed that had such covenants. We are creating the exact same exclusions today, just by shape instead of text.

A Non-Baseplate

Fixing subdivision may begin separate from the ordinance. Individual property ownership is attractive because the alternatives are undesirable or misunderstood. Condominiums require a condo board and are kind of a pain in the butt in Washington. Co-ops are fantastic, but struggle to take hold in the United States. If we want an alternative to atomized land ownership, rules and financing for co-ops and condos need to be streamlined, simplified, and publicly legible.

On the flip side, land ownership with mortgages are favored through decades of racist tax credits and more racist suburb building. Our legal structure favors owning a house with its own land through cheap money and simplified text. So simple, robots can do it. Over the years, other cities have developed varied structures because of their unique ways of setting up taxes. Often, it was by separating value of the house from the value of the land. We can do it while remaining within Washington’s rules about taxing similar assets similarly.

Within the ordinance, we must reconsider the kind of entitlements that subdivision creates. Instead of using simplified scales based on the number of homes, we can require a more nuanced approach including benefits based on homes per parcel or novel approaches that don’t include long, ridiculous easements or erratic lot lines. Compactness, as in election districts, should be a goal of property boundaries. Attach the costs of development to the number of lots created or the length of property lines drawn and not the number of homes built. Or allow the vertical division of property without the weight of traditional condominium agreements.

It may seem like people have the right to sell off property in the ways they want, but we do put limits on that. You can’t sell your house out from under your spouse. You can’t set up spite strips to deny access to your neighbor (usually) or sell rights under your land that can make your neighbor’s property collapse (usually). You can’t sell off beach below high tide or give a deed to the Brooklyn Bridge. Similar safeguards should be in place to prevent shredding the city into atoms.

Most LEGO sets don’t come with those big flat baseplates any more. Newer sets get built around an armature where you set up a vertical frame, then build modules that attach on all sides. Even the big castle sets have several smaller flat plates that can be moved and rearranged to stack a completely new playset. They make for ridiculously awesome sets.

Perhaps our challenge is to move our subdivision mindset away from the simple parceling out of land and entitlements. The flat, indelible lines of subdivision are just as inflexible as the old flat LEGO baseplates. We are developing newer ways of thinking about layers of space in our cities, including different methods of ownership and the ways they impact our communities. Such creativity will require a legal armature that is not subdivision, but which will lead to some ridiculously awesome cities.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.